Jeffrey Simpson is the author of eight books and the former national affairs columnist for The Globe and Mail. This essay is adapted from a speech delivered at St. Francis Xavier University on Oct. 20.

Here’s a conundrum or a contradiction: Canada’s Liberal Party has won three elections in a row, yet it has been in long-term decline for some decades.

For much of the 20th century, the Liberals were the world’s most successful democratic party, winning more elections and staying in power longer than any other. They were “Canada’s natural governing party.” And yet, the Liberals retained power in the last election with the smallest share of the popular vote for a “winning” party in Canadian history. Polls taken since the last election, for what they are worth, show little movement in the Liberals’ favour despite tens of billions of dollars spent during the pandemic and a subsequent summer showering the country with announcements of fresh spending.

Under Canada’s first-past-the-post system, seats rather than share of the popular vote dictate which party forms the government. The Conservatives pile up huge majorities of the popular vote on the Prairies, and in rural British Columbia and Ontario. These majorities, however, provide fewer seats than the ones captured by the Liberals in and around Vancouver, Montreal, Ottawa and especially Toronto. In two consecutive elections, the Liberals won fewer votes than the Conservatives but enough seats to form minority governments.

In the last election, the Liberals won 32 per cent of the vote. In 2019, they took 33 per cent, a six-point slide from 2015 when they attracted 39.5 per cent. These totals compare unfavourably with popular-vote shares amassed by Liberal prime ministers Jean Chrétien and Paul Martin in winning the elections of 1993, 1997, 2000 and 2004: 41 per cent, 38.5 per cent, 41 per cent and 37 per cent. Pierre Trudeau, Justin’s father, led the party in five elections from 1968 to 1980, during which the party’s share of the popular vote was 45.5 per cent, 38.5 per cent, 43 per cent, 40 per cent and 44 per cent.

Put another way, Liberal victories under Justin Trudeau were won with an average share of the popular vote of 35 per cent, compared with 39 per cent under Mr. Chrétien and Mr. Martin, and 42 per cent under Pierre Trudeau. In a late-September poll this year by Leger, the Liberals stood at 28 per cent, six points behind the Conservatives. An Angus Reid Institute survey, taken at the same time, showed the Liberals with 30 per cent, seven points behind the Conservatives. A new Nanos poll, released this week, puts the Liberals at 30 per cent, six points behind the Conservatives.

At the provincial level, the Liberals are in desperate shape. They govern only one province in Canada: Newfoundland and Labrador. Conservatives are in power in the other Atlantic Canada provinces. The once-mighty Liberal Party of Quebec is now a rump largely confined to non-francophone ridings. In Ontario, the party finished third in the last two provincial elections. The Liberals’ standing on the Prairies is so weak that one might paraphrase what prime minister John Diefenbaker once said of his Progressive Conservatives in that region: The only laws protecting Liberals are the game laws. In British Columbia, although there is a “Liberal Party” as the Official Opposition, that party is an unwieldy coalition of people who dislike the New Democrats more than they like each other.

Federal-provincial political fidelity, it should be noted, does not always bring harmony. Fierce rows have sometimes defined relations between Liberal premiers and Liberal prime ministers. There has also been a pattern for either party in power in Ottawa to lose ground provincially. Strong provincial partners, however, bring volunteers and money at federal election time.

Provincial Liberal governments can also provide a proving ground for candidates and political staff who land later in Ottawa. At no time was that more evident than when so large a raft of staffers from the former Ontario Liberal government of Dalton McGuinty swarmed into Justin Trudeau’s government that Ottawa might jocularly have been called Toronto-on-the Rideau.

Nor is there much left of a national Liberal Party organization. Today, anybody can join the party, no money or long-term commitment required. Just show up and be counted, then disappear. Long gone, too, are regional ministers with clout and power in cabinet and among the rank-and-file. These posts, a hallmark of many former Liberal cabinets, were scrapped by Justin Trudeau, one example of power centres collapsing in the face of governing by the Prime Minister and his entourage.

Prime Minister Justin Trudeau sits between his deputy, Chrystia Freeland, and the Governor-General, Mary Simon, at the cabinet swearing-in on Oct. 26, 2021.Justin Tang/The Canadian Press

A party leader in the Canadian system has always been primus inter pares. When cabinets were smaller (today’s Liberal cabinet is a bloated 39 members), some ministers were serious heavyweights in their regions. They had to at least be noticed by the prime minister, if not always followed. They were stabilizing cogs in the Liberal Party, but they are now gone, replaced by Prime Minister-as-Sun King surrounded by his circle of advisers and, when called upon, pollsters.

This kind of political leadership can work to build and maintain support on one condition: that the prime minister remains reasonably popular in the country. Alas for the Liberals, Mr. Trudeau’s popularity has been sliding, a fate not unknown to prime ministers after a while in office. In the last two elections, he fortunately faced lacklustre, even incompetent, Conservative Party leaders. Time will tell whether Pierre Poilievre performs better, and whether he recognizes there are more available votes toward the middle of the country’s political spectrum, shrunken as it has become, than on the right-wing fringe.

The Liberal vote is due partly to the fracturing of the party system. The separatist Bloc Québécois now seems a fixture in federal politics. The Trudeau Liberals, rather than defending individual rights in Quebec in contrast to the collectivist politics of Premier François Legault, decided not to confront the popular Premier. Abandoning traditional Liberal principles did them no good politically, as they fell well short of their objective of more Quebec seats in the last election.

The Greens, although a flop in the last election (and in internal chaos ever since), retain a small coterie of voters. The People’s Party of Canada grabbed a few votes, but its members seem to be gravitating to the Poilievre Conservatives. So, yes, fracturing has meant some bleeding from two big national parties. But fracturing alone cannot explain the Liberals’ decline, since the Liberal Party at its zenith accommodated and absorbed protest parties.

Many Canadian voters remain somewhere in the broad, fiscally prudent/socially progressive/proud-of-country Canadian mainstream, which is where the Liberals used to be anchored. These are the voters that the great Liberal strategist of the Pierre Trudeau era, Keith Davey, used to call “garden-variety Canadians.”

There are many reasons tied to the day-to-day decisions and crises that chip away at a party’s support, and all parties evolve. They shift positions according to expediency, the challenges of the time, the priorities of the leader. No party in 2022 would run on the same platform as 50 years ago. That today’s Liberal Party is not the same as it was under Pierre Trudeau, let alone his predecessors, is not surprising. But there are traditions and outlooks that go beyond the turmoil of the day that cause swaths of the electorate to see themselves and their interests and regions reflected in a particular party, and so tend to support it election after election.

Mr. Trudeau joins Grade 2 students in Surrey, B.C., on Oct. 20 to make lights for Diwali and Bandi Chhor Divas, Hindu and Sikh holidays, respectively.Jennifer Gauthier/Reuters

Justin Trudeau, quite apart from this or that decision, has decoupled the Liberal Party from some of its historical moorings, and is paying the political consequences. These moorings – patriotism and respect for Canada’s past; a balance of fiscal prudence and social priorities; defence of a strong central government; a bridge between English and French speakers – defined the Liberals in a positive way for millions of Canadians.

Liberals always had their critics on the right and the left (and among Quebec nationalists), as is the case today. But the party, more than the others most of the time, anchored its appeal in a strong sense of Canadian pride, spending where appropriate but not excessively, defending Ottawa against provincial demands for more autonomy, and reflecting the country’s linguistic duality.

Those moorings are now rusted or gone, and with their departure has vanished some of the Liberal Party’s historical support, which has not been replaced by new sources. Defenders of today’s Liberals would object to this observation and insist, correctly, that the party has gained female supporters. And why not? A gender-balanced cabinet. Budgets defined by “gender.” A “gender-based” foreign policy. A Prime Minister self-described as a “feminist.” More appointments of women to very senior positions than ever before. Spending programs for female entrepreneurs. A new multibillion-dollar child-care plan. And so on.

Any political analyst knows men and women vote for various reasons, of which gender is only one. Nonetheless, the Justin Trudeau Liberals purposefully set about cultivating female voters, and it would appear they succeeded in driving up their support among women.

Simple arithmetic rather than sophisticated political analysis, however, shows that something else happened. If the Liberals’ share of the female vote is going up while the party’s overall share of the national vote is declining, it must mean the vote among men has fallen faster.

The Angus Reid poll cited above illustrates the point. Forty-six per cent of women over 55 prefer the Liberals, compared with 31 per cent of men in that age category. Only 24 per cent of men 35 to 54 years of age prefer the Liberals; just 15 per cent of men 18 to 34 prefer them.

The Liberals have a huge problem with male voters, and they have no idea how to fix it. And that is because whereas there is a feminist vocabulary that the Liberals use incessantly, along with female-based policies, there is nothing equivalent for men. At least not overtly. This targeted Liberal approach is part of a “progressive” thinking in which politics (outside Quebec, with its different political culture) goes beyond gender to appeals based on the identity of race, Indigeneity and sexual orientation. The Liberals under Justin Trudeau have been in the vanguard of this narrative, reflecting and abetting trends in the English-Canadian intelligentsia, cultural and educational institutions, museums and galleries, publishing houses and the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation (but not Radio-Canada).

Sophisticates cringed when Mr. Chrétien used to declare in speeches that “Canada is number one!” The line was so corny, even jingoistic, they said. Audiences did not cringe. That corny cry conveyed two messages: pride and unity. Pride in Canada’s past and confidence in its future. The other, more subliminal meaning of being No. 1 was that for all the country’s differences and diversities, Canadians could be One.

Justin Trudeau’s Liberal Party has turned Mr. Chrétien’s meanings inside out. Mr. Trudeau has apologized more often than any prime minister for more past wrongs while almost never speaking about past accomplishments.

It is entirely appropriate to revisit history and uncover matters once pushed under the rug. It is a salutary exercise for a country to hold up a mirror to its past weaknesses. History is propaganda when it only extols the positive. But history is also propaganda when the mirror of past errors ignores a country’s achievements. When that happens, as it is today, we are no longer talking about a rounded view but about today’s political agendas.

Under today’s Liberals, and for most of the English-Canadian cultural class and institutions, Canada’s past is a sad litany of sins unleavened by triumphs of the human spirit or generosity. Polls – for example, those taken by Angus Reid – show that pride of country has declined among those under 30 years of age, although it remains high among the garden-variety Canadians who do not see that pride in Justin Trudeau’s Liberal Party. The majority of those Canadians are prepared to acknowledge and atone for past sins such as residential schools, but they are not prepared to have their country defined by their Prime Minister and his party as an unbridled legacy of wrongdoing, genocide and racism.

Mr. Trudeau wipes tears at Sept. 30's National Day of Truth and Reconciliation in Ottawa.Sean Kilpatrick/The Canadian Press

Forgotten by the Trudeau Liberals and the English-Canadian cultural elite, it would seem, is that Canada was formed quite improbably. It brought together in the 1860s French Catholics and English Protestants whose ancestors had been fighting in Europe and North America for a long time. Given that history, Canada unexpectedly became the world’s oldest federation born in peace and unscarred by civil war. The resulting country provided a better life for millions of subsequent arrivals while treating Indigenous peoples poorly.

For decades, the Liberals were the party of Canadian patriotism. From the time of Wilfrid Laurier to Mr. Chrétien, the Liberals wanted to place some distance between Canada and Britain and create Canadian institutions, including a Canadian flag, that were opposed by the Progressive Conservatives of the day. Conservatives clung longer and more tightly to the British connection. The Liberals’ appeal to patriotism didn’t always work, as during the party’s fight against free trade with the United States. More often than not it was the party’s high card. Under Justin Trudeau and the identity politics he plays, it has almost entirely disappeared.

There are two kinds of identity politics, as the American political theorist Francis Fukuyama explains in his recent book, Liberalism and Its Discontents. He writes: “One version sees the drive for identity as the completion of liberal politics. … The goal of this form of identity politics is to win acceptance and equal treatment for marginalized groups as individuals, under the liberal presumption of a shared underlying humanity. … The other version of identity politics sees the lived experience of different groups as fundamentally incommensurate; it denies the possibility of universally valid modes of cognition; and it elevates the value of group experience over what diverse individuals have in common.” Mr. Trudeau has chosen the second definition, and in so doing unmoored his party from its classic position as exponent of broad-tent Canadian patriotism.

Mr. Trudeau has also unmoored his party from its traditions in another important way. Every Liberal cabinet as far back as Mackenzie King’s – and throughout Pierre Trudeau’s and Mr. Chrétien’s time – was like a plane with two wings. One wing was composed of what might be loosely called “spending Liberals,” the other “business Liberals.” These are admittedly imprecise definitions for they suggest that the “spenders” were oblivious to the economy, tax and fiscal policy, and the business climate; and that the “business” Liberals lacked a social conscience. But ministers tended to lean in one direction or another, owing in part to what they did before entering politics.

Pierre Trudeau, second from left, walks to a cabinet swearing-in on July 6, 1968. With him, from left, are James Richardson, D.C. Jamieson, John Turner, Jean Marchand and Gerard Pelletier.Doug Ball/The Canadian Press

Thinking back to Pierre Trudeau’s cabinets recalls ministers now likely forgotten but important in their day. There were the “spenders” such as Jean Marchand, Gérard Pelletier, Louis Duclos, Allan J. MacEachen, Bryce Mackasey, John Munro, Monique Bégin and Lloyd Axworthy. And there were the “business” Liberals who had been in the private sector or practised law before entering politics, including Don Jamieson, Edgar Benson, Donald S. Macdonald, Ed Lumley, John Turner, Bud Drury, Bob Winters, Mitchell Sharp and Bob Andras.

Pierre Trudeau, as prime minister, weaved between the factions, especially during the “stagflation” decade of the 1970s, which featured high interest rates, high unemployment and slow growth.

Mr. Chrétien’s cabinet featured the same balance, with spenders offset by business Liberals such as Paul Martin, John Manley, Doug Young, Anne McLellan and Roy MacLaren. Mr. Chrétien himself had a large social conscience but liked to remind listeners that as Treasury Board president earlier in his career he was known as “Dr. No” for turning down spending proposals. His government launched a “program review” that was the most successful postwar effort to cut spending.

Justin Trudeau’s cabinet is quite different. Only two of its 39 ministers worked in largish business companies before entering politics: Innovation Minister François-Phillippe Champagne and Natural Resources Minister Jonathan Wilkinson.

The other ministers, starting with the Prime Minister himself, are teachers, journalists, lawyers, academics, social workers, public servants, engineers, health care workers, police officers, consultants and career politicians. It could be argued that not one has ever met a payroll, and few have experience in private enterprises.

This tilt reflects the political judgment of the Prime Minister and his advisers, and what kind of Liberal Party they believe will be successful. They deem fiscal prudence, often but not always a hallmark of previous Liberal governments, of limited importance. Prudence was ditched even before the first Trudeau cabinet was sworn into office, when a 2015 campaign commitment to balance the budget within four years disappeared. It was replaced by a new target: debt-to-GDP ratio, a much harder idea for the public to grasp than a budget deficit number. “Guardrails,” a loosey-goosey phrase designed to obscure rather than clarify, became the Liberals’ byword for fiscal management.

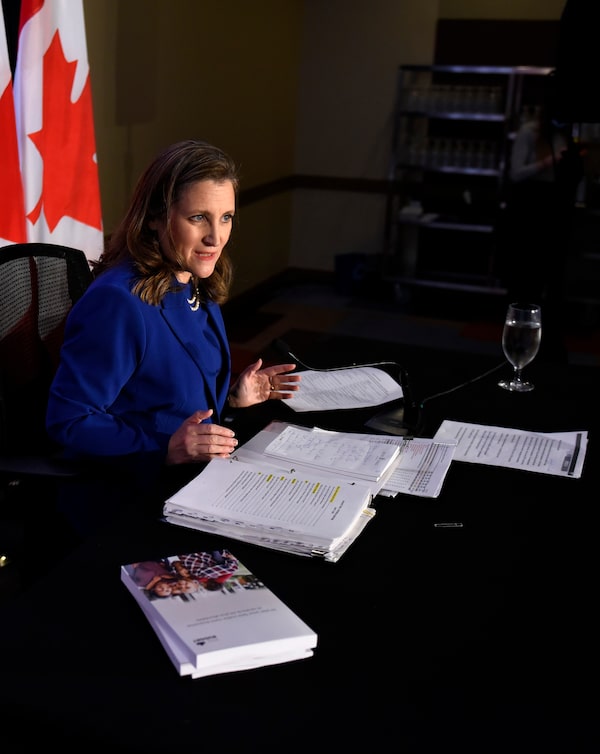

Ms. Freeland speaks in the media lockup ahead of April's budget release in Ottawa.Justin Tang/The Canadian Press

No one could blame the Liberals for ramping up spending during the pandemic. Perhaps some money was wasted, but the COVID-19 situation was unprecedented. Decisions had to be made on the fly in the face of medical uncertainty. After the surge in pandemic-related costs, however, the government announced another $30-billion for a new child-care program and then, as part of a deal with the NDP, a new limited drug-coverage plan and dental care for children. Political survival in the form of the Liberal-NDP deal buried any possibility of spending restraint – even in the face of soaring inflation. The announcement that Treasury Board president Mona Fortier would lead a group of civil servants to find $6-billion in “savings” over five years on government operations bordered on a joke. Even if such “savings” were found they would already have been subsumed by new spending.

The Trudeau Liberals no longer offer a balance between social spending and fiscal prudence. The business Liberals are increasingly extinct and the few that remain are big spenders themselves. Today’s party has decided that the path to political success lies in poaching votes from the NDP. This is surely how they will deal with Mr. Poilievre before and during the next campaign. They will portray him as a dangerous ideologue even further from the Canadian middle ground than the Liberals themselves. Liberals have scared moderate New Democrats into voting for them before, and they will try to do so again. And if Mr. Poilievre, a career politician, is as convinced of his own political genius as he seems to be, buoyed by his huge victory in the party leadership race, he might just provide the Liberals with the kind of target they need.

The Poilievre victory combined with the Liberals’ abandonment of their historic moorings leaves Canadian politics more polarized than it has ever been. Keith Davey’s garden-variety Canadians – socially progressive, fiscally cautious and patriotically proud – have been abandoned by both major parties. Maybe, just maybe, the parties reckon that this kind of Canadian voter has so shrunk in number that today’s politics is less about attracting them than polarizing voters around identity and ideology. In which case it would be naive to believe that Canada might not be witnessing the beginning – in some form – of the sharpened political divisions recently seen in parts of Europe and the United States.

Illustration by Brian Gable

Whither the Liberals? More from The Globe and Mail

John Ibbitson: Trudeau’s aggressive federalism may leave Ottawa weaker than before

Konrad Yakabuski: The Liberals should be worried if Trudeau stays

Campbell Clark: Chrystia Freeland issues a clarion call from Canada’s foreign-policy void