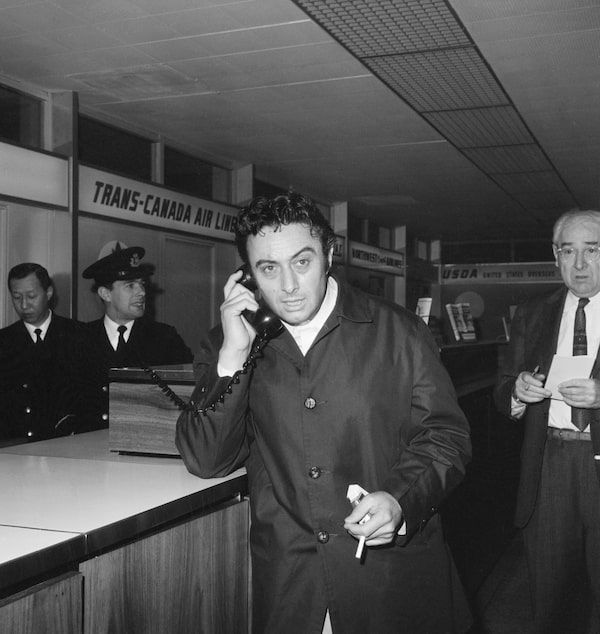

Notorious American comedian Lenny Bruce, seen here at an airport in the early 1960s, provoked controversy throughout his career. His performance at Isy’s Supper Club in Vancouver was trashed by a Vancouver Sun columnist: ‘It is not a decent or acceptable show. … It is indecent and improper for Vancouver.’Bettmann/Getty Images

Kliph Nesteroff is the author of three books about the history of comedy. His latest is Outrageous: A History of Showbiz and the Culture Wars.

In February, a handful of conservative media outlets reported on their latest example of “cancel culture” – this time at Seattle’s Capitol Hill Comedy/Bar. The club’s management had cancelled a show, which had been set to feature comedians Kurt Metzger, Dave Smith, Luis J. Gomez and Jim Florentine, after learning the comics were right-leaning and at least one was known for making jokes about transgender people, something they deemed a poor fit for their progressive, queer-friendly club. The hyperbolic coverage of the event included a banner on Fox News proclaiming “SEATTLE LOVES DRUGS, HATES COMEDY.”

The incident was one of many in recent years where pundits and comedy fans fretted that “cancel culture” and “woke millennials” are threatening the future of comedy. The fear is that comedy – in the form of stand-up, movies, TV and internet content – is under attack and struggling to survive. For years, we have been told that college students are too sensitive, that the “PC police” are coming to get us, and that we live in an environment where you “can’t joke about anything any more.”

High-profile controversies involving comedians such as Matt Rife, Ricky Gervais and Montreal’s Mike Ward are used to illustrate the pattern. After Dave Chappelle was assaulted at the Hollywood Bowl and Chris Rock was assaulted at the Oscars in 2022, veteran Canadian comedian Howie Mandel concluded it was “the beginning of the end for comedy.” Everyone from John Cleese to Dr. Phil has made a similar argument.

But does the argument hold up to scrutiny?

In my capacity as a comedy historian – a job that I quite literally made up and then fulfilled – I am frequently asked to comment on the belief that “you can’t joke about anything any more.” Unquestionably, comedy faces frequent controversy and increased sensitivity regarding race and gender, but if one were to weigh our modern taboos against what was forbidden throughout comedy history, it’s clear that far more taboos have been shattered than new ones established.

Comedy is not dying. Arguably, it is thriving to an extent greater than ever before. But it’s easy to believe otherwise when presented with a daily diatribe about millennials and “woke mobs” who have supposedly robbed us of our favourite subject matter.

If you study comedy history, you’ll discover very similar complaints to the ones being made today. “Americans are losing their sense of humour,” comedian Jack Albertson complained in 1954. “No longer will anyone laugh at himself. Minority groups carry chips on their shoulders … this makes life rough for the comedian.”

Charles W. Morton, a literary humorist, complained in 1955, “It is becoming more difficult for us to laugh at ourselves. Everybody’s terribly cautious. They’re afraid of offending someone.”

“We’re afraid to laugh,” The Saturday Evening Post lamented in 1958. “What else is left to laugh at? One by one we’ve herded all our sacred cows behind a barbed-wire fence of patriotic or social or racial sensitivity. If a comedian trespasses inside, he is promptly punished.”

Despite the similar sentiment, the taboos that comedy had to contend with back then were actually far greater than those of today. Nudity, sexuality, religion, politics and cuss words were forbidden subject matter for most of the 20th century – and Canada, still tied to the stuffy British, was especially repressive in this regard. After a Scottish vaudeville comedian named Clifton Crawford toured Canada in 1910, he told people back home, “Canadians can’t take a joke.”

The notorious American comedian Lenny Bruce was booked at Isy’s Supper Club in Vancouver for a two-week engagement in 1962. His material included criticism of organized religion and general comments about sexual behaviour. His first night was trashed by a Vancouver Sun columnist: “It is not a decent or acceptable show. … It is indecent and improper for Vancouver.”

Bruce’s material was tame by today’s standards, innuendo rather than explicit, but it alarmed the Vancouver Police Department. They sent their “morality squad” to threaten the venue’s business licence, and Bruce’s engagement was cancelled.

Bruce’s language and criticism of religion were nothing compared to a modern program such as The Righteous Gemstones. HBO’s religious satire is filled with profanity and full frontal nudity, and the sight of a man’s privates has garnered little comment or controversy. Compare it to the reaction to Janet Jackson’s Super Bowl nip slip just 20 years ago. The protest decrying that moment was tremendous, with politicians and evangelicals forecasting the downfall of society.

Comedian Gilbert Gottfried did a series of masturbation jokes at the Emmy Awards in 1991, which, despite big laughs at the ceremony, was condemned by critics, talk radio and even the Emmy producers themselves. Compare this with a modern comedy program such as Bupkis starring Pete Davidson, which not only references masturbation, but shows the famous comedian in the act. Not only was there zero protest, but most people haven’t even heard of the show.

The way Lenny Bruce was treated by Canadian authorities in 1962 was no anomaly. Back then the threat of arrest was a serious concern for any comedian who breached the established order. Canada’s puritan laws were informed by British colonialism and any parody of religion, politics or the Royal Family was taboo. The Ontario Board of Censors’ guidelines for silent movies in 1921 called for “a respectful presentation of all British flags. Burlesques or scenes of ridicule of clergy, Salvation Army or any other religious work will be eliminated.” These types of rules covered all genres, from comedy to drama, stage to film, for decades.

Political censorship was common. In January, 1964, Rich Little, then a young comedian-impressionist, was banned from “presenting religious and political spoofs” at Toronto’s Royal York Hotel. Mr. Little was making a name for himself with mimicry of prime ministers John Diefenbaker and Lester B. Pearson. According to the Windsor Star, “A hotel spokesman said that the management banned the Little satire because it doesn’t want to offend customers.”

The CBC was terrified of upsetting Parliament Hill throughout the 1950s and 60s. The author of a critical book about former prime minister Mackenzie King was removed from a CBC panel in 1956. A documentary about Pearson was shelved in 1964 because the prime minister had sworn while watching a baseball game. A novelty song about Pierre Trudeau was banned from CBC Radio in 1968 because the broadcaster felt it would “upset the balance it tries to maintain during an election campaign.”

Some of the established taboos eroded after the 1960s as anti-war protests, LSD use and “free love” altered the cultural landscape, but Canadian authorities did not allow changing social mores to stop their attempts at censorship. A young student filmmaker at McMaster University named Ivan Reitman, later the director of Ghostbusters, was arrested by the Hamilton police in 1969. Mr. Reitman was screening The Columbus of Sex, an avant-garde comedy he produced about a sex maniac in the Victorian era. The film was confiscated. Mr. Reitman was arrested – and convicted – of “visual and aural obscenity.”

Long before Chris Rock was slapped and Dave Chappelle was attacked, comedians were randomly assaulted. Michael Dugan had just finished performing at the Improv in Santa Monica, Calif., in 1991 when an angry audience member followed him into the parking lot. Objecting to his jokes, he punched the comedian in the stomach, slammed his head against the hood of a car, and then kicked him in the face until his nose was broken. That same year, Jerry Sadowitz was punched in the face repeatedly by an audience member who rushed the stage during a stand-up performance at the Just for Laughs festival in Montreal after he insulted French Canadians.

Throughout the 1970s and 80s, if comedy referenced homosexuality, it was frequently objected to by right-wing evangelicals who considered it immoral, or protested by left-wing activists who considered certain depictions or commentary homophobic. The sitcom Three’s Company featured John Ritter’s character pretending to be a gay man so his landlord would not object to his co-ed living arrangement. An evangelical campaign targeted the program’s sponsors and Sears pulled their commercials.

Stand-up comedians Eddie Murphy and Sam Kinison were accused of homophobia and spreading disinformation about the AIDS virus. Several of their concerts were picketed throughout the 1980s. In 1992, the City of Vancouver banned comedian Andrew Dice Clay from performing in publicly funded venues because his act showcased “unwelcome conduct of a sexual nature that is intimidating, hurtful, threatening or malicious.”

If one were to believe the YouTube comments section, the early 1990s were a glory day for comedy in which nobody ever complained. But the decade was a whirlwind of pressure groups, protest, criticism and censorship. It’s something our modern opinion makers have either forgotten or willfully ignore. In the early 1990s, president George Bush denounced The Simpsons, vice-president Dan Quayle condemned the sitcom Murphy Brown and Bill Cosby accused The Fresh Prince of Bel-Air of “soiling Black culture and setting back the course of Black television progress.” The California Bar Association attempted to classify “lawyer jokes” as hate speech. The Disney blockbuster Aladdin was edited for its VHS release when Arab-American groups objected to lines referring to Arabs as “barbaric.” Walmart banned Beavis and Butt-Head merchandise from its stores and the MTV characters were dropped by several cable providers after the show was accused of inciting arson.

These decades-old examples, if they occurred today, would inevitably be used to demonstrate cancel culture run amok. Voices in the political culture war with no relation to comedy, from commentator Tucker Carlson to author Jordan Peterson, have made the argument that comedy is under attack today as never before, chiefly blaming liberals who object to bigotry. Thousands have fallen for this argument, but the historical evidence clearly contradicts it. So why has their argument been so effective?

Throughout the 20th century, hostile grievances were published as letters to the editor in newspapers, magazines and TV Guide. They were always moderated, selected or filtered by an editor. In those days, perhaps one out of every hundred complaints would be published and the rest discarded. But today, social media has removed the editor from the equation and every hostile expression is published automatically.

Instead of just one hostile letter, we see hundreds of simultaneous tweets. The absence of the traditional filter gives the impression that people are more irrational, more humourless and far more sensitive than in the past. But the vitriol found in vintage letters to the editor is very similar to the sentiment found on social media today.

Contrary to the continuing doomsday prophecy, comedy is not dying. It’s not even suffering. Controversies arise and online hostility abounds, but comedians are filling stadiums and there are several comedy podcasts with millions of listeners and hundreds of thousands of paying Patreon subscribers. The largest cities have hundreds of stand-up shows occurring each week, the most popular venues are consistently packed, and unlike Lenny Bruce, comedians are free to express themselves without fear of arrest.

Despite the recent implosion of the Just for Laughs festival, several major comedy festivals – Moontower, the Netflix is a Joke Festival, and SF Sketchfest, just to name a few – have been thriving ever since the lifting of COVID restrictions. There is currently more freedom of expression thanks to streaming services, satellite radio, cable television and podcasts – certainly more than at any other point in comedy history. Of course, there will be those who object to some of it, sometimes irrationally and sometimes with great justification. Meanwhile, comedy survives.