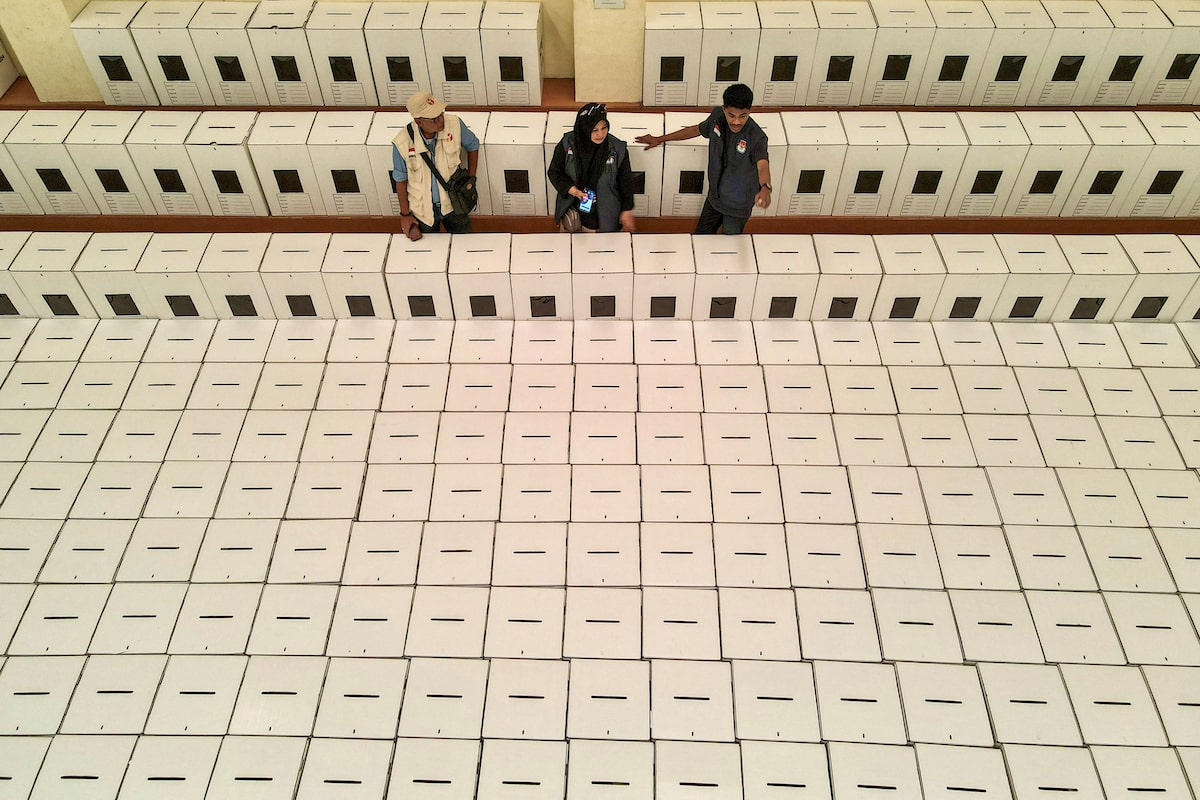

The year ahead, from one perspective, will be the most successful democracy has ever seen. Never in history will so many people have the opportunity to put a mark on a ballot: More than half the world’s almost six billion adults will go to the polls in some sort of nationwide vote in 2024, according to an estimate by The Economist.

Those elections will include some of the world’s biggest and most populated countries – India, Indonesia, Pakistan, Bangladesh, Russia, Mexico, the United States, and likely Britain and Canada, will have a major vote in 2024, as will the European Parliament. You could call it a high-water mark for democracy, if the success of democracy were measured only by people voting.

But it’s not. A democratic life in a free society means a lot more than having an election – it requires a robust and legal opposition, a free and unfettered press, full rights and freedoms for all citizens, full inclusion of national minorities and women, an independent judiciary, a military and police force that serve the constitution and not the leader, a critical parliament, and a confidence that those elections can lead to a peaceful change of leadership.

The past dozen years have seen a rapid rise of leaders and prominent candidates who have threatened or outright abolished many of those foundations of democracy – despite continuing to hold elections. As such, 2024′s torrent of ballots is being anticipated by informed observers not with celebratory toasts, but with deep anxiety and ominous foreboding, though also with a glimmer of hope.

Many of those elections will be crucial tests of the very basis of liberal democracy in their countries and regions – and some countries will fail. It has led some observers to describe 2024 as a global make-or-break year for democracy.

Trump supporters in West Palm Beach, Fla., question the legitimacy of the last election, and call for victory in the next one.Evan Vucci/The Associated Press

Most crucial will be the Nov. 5 presidential election in the U.S., whose outcome could set the temperature of democracy worldwide. But while Donald Trump’s sometimes violent assaults on democratic institutions and outspoken alliances with overseas autocrats, if returned to world politics in a second presidential term, have the ominous potential of cementing a worldwide far-right authoritarian bloc, he is far from the only democracy-threatening candidate on the ballot next year.

Nobody pretends that Russia’s March election will be anything other than a coronation of President Vladimir Putin, with all his credible opponents either dead or vanished into prisons. We have recently seen his example followed by other far-right leaders including Hungary’s Viktor Orban, Turkey’s Recep Tayyip Erdogan, India’s Narendra Modi and Israel’s Benjamin Netanyahu, all of whom have held power by reducing the power of the courts and the democratic opposition to stop them.

Mexican President Andrés Manuel López Obrador, who has stacked the courts with supporters, recently vowed to shut down democratic oversight agencies and end freedom of information laws in advance of a June national election.

The Sweden-based International Institute for Democracy and Electoral Assistance, in its 2023 report, described 2022 as “the sixth consecutive year in which more countries have experienced net declines in democratic processes than net improvements.” And 2023 will almost certainly prove to have been a seventh – “democracy has continued to contract,” its analysis found, with declines of at least one major democratic measure in half the world’s countries.

That includes some complete democratic reversals – a wave of military coups, often with apparent Russian backing, that swept across Africa in 2022 and 2023, turning erstwhile democracies including Gabon, Niger, Burkina Faso, Sudan, Guinea, Chad and Mali into military autocracies. The military has similarly seized control, at least until February’s election, in Pakistan, and effectively controls Egypt, under the guise of a highly undemocratic electoral system.

But the biggest reversals of democracy in recent years have not come from outright coups or shifts to dictatorship or from revolutions in the name of some alternative, non-democratic ideology.

Rather, they are instances of “democratic backsliding,” to use a term popularized in an influential 2016 paper by University of Oxford political scientist Nancy Bermeo. She noted that coups and overthrows have become relatively rare this century, but that there’s been a big rise in centralization of power by prime ministers and presidents, in manipulation of elections and courts to guarantee a one-party victory, in use of police and military and disempowerment of legislatures to guarantee a pseudo-democratic hold on power. “De-democratization today tends to be incremental rather than sudden,” she wrote. “troubled democracies are now more likely to erode rather than to shatter – to decline piece by piece instead of falling to one blow.”

The Varieties of Democracy Project, another Swedish democracy-monitoring organization, found in its recent report that the number of full-fledged liberal democracies declined from a peak of 44 in 2009 to only 32 last year; while “electoral autocracies” – countries with elections but with one party or leader more or less permanently in power, such as Russia – have risen from 35 in 1978 to 56 in 2022, making them the second most common type of regime.

The biggest rise has been in non-liberal democracies – countries with elections but without the institutions and rights of democracy – which have risen from 16 in 1972 to 58 today, making them the most common form of regime. Most of them, the report concludes, are not the result of autocracies gaining democracy, but of liberal democracies experiencing backsliding.

There are fears that other countries are on the way to joining that club, after a recent series of electoral shocks in Western countries. November’s election in the Netherlands alarmed many observers by delivering the largest vote share – more than 23 per cent – to the extreme-right party of Geert Wilders, who campaigns almost exclusively on policies of racial intolerance and withdrawal from democratic institutions including the EU. (It is not clear that he’ll be part of a government.)

That followed polls and regional elections in Germany that showed the far-right Alternative for Germany, also devoted almost entirely to intolerance and opposition to democratic institutions, has risen to second-place status in some states and might end up governing in the state of Saxony, where it won its first-ever mayoral election in December. In Italy, Giorgia Meloni, whose Brothers of Italy party is often considered neo-fascist, became prime minister in October, 2022, on a platform of opposition to racial and sexual minorities.

Yet the last year has provided some hopeful signs that the backslide can be reversed, even in countries where would-be authoritarians have managed to demolish many of the institutions of democracy.

The most impressive example of what might be called “fore-sliding” is Poland, where October’s election put a decisive end to eight years of rule by the extreme-right Law and Justice (PiS) party, which had stacked the courts to prevent legal challenges, passed laws that severely curtailed the rights of women, minorities and homosexuals, and eventually even shut the border to Ukrainian refugees and exports. The return of Donald Tusk’s democratic, pro-European coalition proved that even entrenched authoritarians can be ousted by a determined people.

The Polish victory was preceded, a year earlier, by a Brazilian election that drove hard-right strongman Jair Bolsonaro out of office, after he had engaged in Trump-inspired campaigns against the courts, the parliament and the institutions of democracy, sometimes with support from branches of the military.

Those two milestones, added to the successful 2021 U.S. transition of power in the face of Mr. Trump’s use of insurrectionary violence, have given some observers hope that the end of the global backslide might become visible in 2024.

“Both were fantastic news for liberal democracy and empowering for liberal democrats, though they were fairly different and quite country-specific,” said Cas Mudde, a Dutch political scientist at the University of Georgia whose work examines the rise of illiberal far-right parties in Europe. However, he cautioned that both victories were narrow, and left openings for the anti-democratic leaders to return to power – as remains the case in the United States. “If anything, they show that if you want to defeat a far-right government, you need to make very broad coalitions and have a clear message that focuses on liberal democracy,” he said. “But they show that the far right does not only win.”

They also suggest that illiberal-democratic leaders and parties are not necessarily on a perpetual rise that will roll the free world back to a tiny stronghold pinned down by a global coalition of angry autocrats. Instead, they might be better understood as part of a cycle.

To understand where we are, it’s worth flipping the calendar back 50 years to another important year for democracy. In 1974, the flourishing of democracies in the 1950s and 60s had declined to a sliver. Democratic Europe was limited to a northwestern corner – and not just because of the stark ideological divide around the Iron Curtain. A number of countries on the “Western” side – Greece, Spain and Portugal – began 1974 as right-wing dictatorships. By the end of the year, Cyprus would join them in a military coup, though both Portugal and Greece would “fore-slide” back into the beginnings of democracy later that year.

By 1974, India had ceased to be the world’s largest democracy, as Prime Minister Indira Gandhi cracked down on civil liberties and took control of courts and institutions; by the following year, she had ended elections, shut down the media, imprisoned political opponents and ruled by decree in a years-long “emergency.” South Korea was just as authoritarian as North Korea is today, and nascent democracies in Southeast Asia had mostly slipped back into authoritarianism of various forms. In South America, the military declared Augusto Pinochet, who had seized power the year before with their help, a full-scale dictator, a deadly move joining a series of backslides that left Latin America, by the end of 1974, with fewer democracies than it had in 1955.

That year marked a near reversal of the “second wave” of democracy, which had flashed across the world with the end of the Second World War and the end of European colonialism. Nobody watching the developments of 1974 could have guessed that the next 15 years, culminating in the democratic revolutions of 1989, would see a powerful third democratic wave paint most of the world’s citizens democratic, officially at least, for the first time in human history.

U.S. secretary of state Henry Kissinger greets foreign ministers from Chile, then under a military dictatorship, and Argentina, which would follow suit in 1976.Ed Kolenovsky/The Associated Press

Fifty years ago, it seemed more likely to many that authoritarianism would continue to expand. After all, it had marketing appeal.

The world’s socialist dictatorships, for the last time in history, could still claim to offer a completely alternative system of government, revolutionary or collectivist rather than merely un-free. Right-wing autocrats claimed to offer a more secure and peaceful life to those who did not challenge them, an appealing message in countries that had been racked with riots and revolutions. The worldwide petroleum crisis was at its height, accompanied by crises of inflation and unemployment that left citizens of many democracies visibly poorer and less happy than in previous decades. And the U.S., still stuck in Vietnam, embroiled in the deep political corruption of the Watergate scandal and providing support for many of those Cold War coups and autocracies, had ceased to be an ideal example for many of the world’s people.

What caused democracy to spring back to life, over the next 15 years, can also largely be credited to marketing – or certainly to a failure of marketing on the authoritarian side. By the 1980s, communist-bloc countries were falling into poverty and decay, deeply indebted to Western lenders and relying on the blows of the hammer far more than the harvests of the sickle to keep their populations in line. Closed and nationalist economies, whatever their ideology, were providing a far lower standard of living than open, global states. And the crimes and atrocities of autocrats were becoming far more difficult to conceal from their publics in an age of electronic media. The democrats didn’t just have freedom to offer, but a very visibly better, safer, more exciting quality of life.

'We are with him for the sovereignty of Russia! And you?' reads a poster of President Vladimir Putin outside the Duma legislature in Moscow.KIRILL KUDRYAVTSEV/AFP via Getty Images

Today, we are in the midst of a democratic backslide almost approaching the scale of the one that reached its nadir in 1974, as democracy’s third wave enters a trough. But there are a number of reasons to believe that 2024 could be another 1974 in the more optimistic sense – that is, the end of a decline, or perhaps the beginning of a fourth wave.

For one thing, the autocrats no longer have the marketing edge that drove much of the democratic backslide of the 2010s, whose beginning coincided with the global economic crises of 2008. China’s descent into economic decline this year, Russia’s shift into a total-war economy, isolation and heavy-handed repression have reduced the appeal of their models. The economic boom taking place in North America, now that inflation has largely abated and full employment and high wages are getting noticed and governments are spending more on the well-being of their citizens, is making their example more appealing abroad (though not, for reasons that remain mysterious, to half the voters of the U.S. itself).

And that’s another difference: Unlike during the last democratic backslide 50 years ago, the autocrats no longer have an alternative system of governance and economy to sell. There is no Iron Curtain between competing systems, no global alternative to electoral democracy and a liberal-market economy, just individual parties and leaders who seek to hold lifelong power under that guise. Strongman leaders no longer claim to be putting their muscle behind a superior economic or political system; today they merely claim to be strong.

That’s the core observation of U.S. political scientist Larry Bartels in his recent book Democracy Erodes From the Top. There has not been any significant change in mainstream public beliefs in most countries – in fact, European and North American voters, especially those under 50, are measurably more liberal and democracy-minded than people of the same age a generation ago. What has changed is merely the emergence of elites and political candidates who are able to manipulate minority beliefs and fears to seize power. In most countries where illiberal candidates have won fair elections, including the U.S., they’ve never won the support of a majority of voters (Hungary is a rare exception). It is more often the failure of mainstream parties to hold majority coalitions together and satisfy voter needs, rather than an upwelling of authoritarian-minded beliefs, that allows the anti-democrats to get power – and, once they have it, they try to manipulate the system to keep it.

A protester in Washington mocks Mr. Trump for his belief in the 'divine right of presidents.'Jacquelyn Martin/The Associated Press

The Harvard University political scientist Pippa Norris, whose work has chronicled the cultural roots of democratic decline, says that this fragile hold on power is the key to preventing further backsliding.

“Democracies can come back, in particular because there are strong democratic norms and values in the heart of cultures, which are slow to change,” Dr. Norris told a symposium at Carleton University in November. “However, the problems occur when these [illiberal] leaders and parties come back over successive terms of office. Then the risks increase, as those who are more authoritarian manage to use the capacity of the state to weaken elections, to weaken public trust in things like the independent media, to produce corruption and erode rule of law, and a variety of other institutional changes which are much more difficult to resist.”

That’s how seemingly autocratic-minded leaders such as Mr. Putin in Russia, Mr. Orban in Hungary, Mr. Erdogan in Turkey, Mr. Netanyahu in Israel and, quite possibly, Mr. Modi in India have managed to become such seemingly permanent fixtures. But it’s also why there’s hope in one-term countries such as Brazil and the U.S., where hard line leaders have generally governed against, rather than with, the larger public will. And Poland showed this year that even multiterm electoral autocrats who have heavily vandalized the machineries of democracy can be forced to leave office.

That said, the politics of electoral authoritarianism, or far-right populism, or illiberal democracy – the lack of a common name says much about its fragile hold on power – are not going away. It is now normal, in most established democracies, for an authoritarian-minded party to be on the ballot and regularly attract 15 per cent or 20 per cent and even occasionally more of the vote. And as Dr. Mudde notes, the reason why those parties haven’t done any better is because mainstream conservative parties have deliberately adopted much of the rhetoric and policy ideas of the strongman right in much of Europe, in the U.S., and possibly even in Canada. “There’s no longer a taboo against voting for those ideas,” he says.

Which is why so many of the elections of 2024 will be historic events: Many of them will show us whether the democratic backslide was a one-time venting of voter frustration during bad times, or a more lasting, possibly irreversible end of democracy’s long-ago third wave.

Democracy and its discontents: More from The Globe and Mail

Since the unexpected success of Dutch far-right parties in November, Europeans have been worried about illiberalism in their midst. Columnist Doug Saunders explains. Subscribe for more episodes.

Ami Pedahzur: How the far right grabbed power in Israel, and what it means in this time of war

Timothy Garton Ash: Poland’s great democratic moment is good news for all of Europe

Doug Saunders

Doug Saunders