President Donald Trump making his national televised addresses from the oval office on March 11, 2020, about the growing coronavirus pandemic.The Globe and Mail

David Shribman, the former executive editor of the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, won a Pulitzer Prize for coverage of U.S. politics. He teaches American politics at McGill’s Max Bell School of Public Policy

Article II of the United States Constitution sets out the responsibilities of the president: to serve as commander-in-chief of the armed forces, appoint executive officers of the government, make treaties and nominate judges. Nowhere in that 231-year-old document did the American Founders stipulate that the president should be pastor to the nation, feeling its pain, salving its wounds, proving solace and consolation at times of sorrow, inspiration and determination at times of challenge.

And yet the American presidency has evolved from a strictly political office into a pastoral calling, with the country’s chief executive often called upon to counsel, console and comfort a continent-wide superpower of about 330 million people.

“Given the high public profile of the presidency in modern times, the expectation is that he will speak to disasters,” said Stephen Skowronek, a presidential expert at Yale University. “It’s become part of the job.”

Over the years, presidents have held the hands of the war wounded (Abraham Lincoln), urged Americans to resist fear itself (Franklin Delano Roosevelt), steeled Americans against the scourge of polio (Dwight Eisenhower), joined Americans in mourning the dead in space accidents (Ronald Reagan), spoken of rage and remorse at domestic terrorism in Oklahoma City (Bill Clinton), urged forbearance in the face of an incomprehensible terrorist barrage (George W. Bush), and sought healing after devastating school and church shootings (Barack Obama).

U.S. President Franklin Delano Roosevelt at his desk in this file photo from 1936. A Democrat, he led his country through the depression of the 1930s and the Second World War, and was elected for an unprecedented fourth term of office in 1944.Keystone Features/Getty Images

“Americans,” said Skip Rutherford, a close adviser to Bill Clinton and now the dean of the Clinton School of Public Service at the University of Arkansas, “look to their presidents to be ‘comforters-in-chief’ during times of tragedy, crisis and despair.”

It was that impulse that prompted Donald Trump – awkward in the pastoral role of the presidency, more accustomed to deliver a putdown than to uplift, unpractised in the arts of sensitivity – to undertake an Oval Office address Wednesday night on the coronavirus. His speech was one part response (a ban on most travel from Europe) and one part resolve (“This is just a temporary moment in time that we will overcome together as a nation and as a world”).

Mr. Trump’s remarks – given at the presidential desk made from the oak timbers of the 19th century British ship HMS Resolute – was an attempt to fulfill public expectations of the pastoral presidency even as he attempted to fill the void created by his reluctance to acknowledge the severity of the threat and the confusion sowed by his contradictory statements.

U.S. President Dwight D. Eisenhower stands second from right at a session of the third International Polio Congress at Rome University in Italy, in this file photo from Sept. 8, 1954.The Associated Press

He checked the box setting out the pastoral requirements of his office, to be sure. But whether he comforted a nation terrified of the spread of the virus and divided over the conduct and tone of the President himself was less certain. His supporters thought he dispatched the task splendidly. His opponents saw him as self-serving, bombastic and tone-deaf. And skeptics noted that his speech, which at times had the air of a campaign rally, held out false hopes for a swift end to the crisis and came after a series of misleading presidential remarks and repeated efforts to play down the threat.

“If there ever were a time for a president to comfort us, to inspire confidence that he knew what he was doing, to tell us everything will be all right, this was the time,” said Martin Kaplan, a specialist in media and society at the University of Southern California. “On every one of these tests he has miserably failed.”

If I read the temper of our people correctly, we now realize as we have never realized before our interdependence on each other; that we can not merely take but we must give as well; that if we are to go forward, we must move as a trained and loyal army willing to sacrifice for the good of a common discipline, because without such discipline no progress is made, no leadership becomes effective. We are, I know, ready and willing to submit our lives and property to such discipline, because it makes possible a leadership which aims at a larger good.

– Franklin Delano Roosevelt, inaugural address, March, 1933

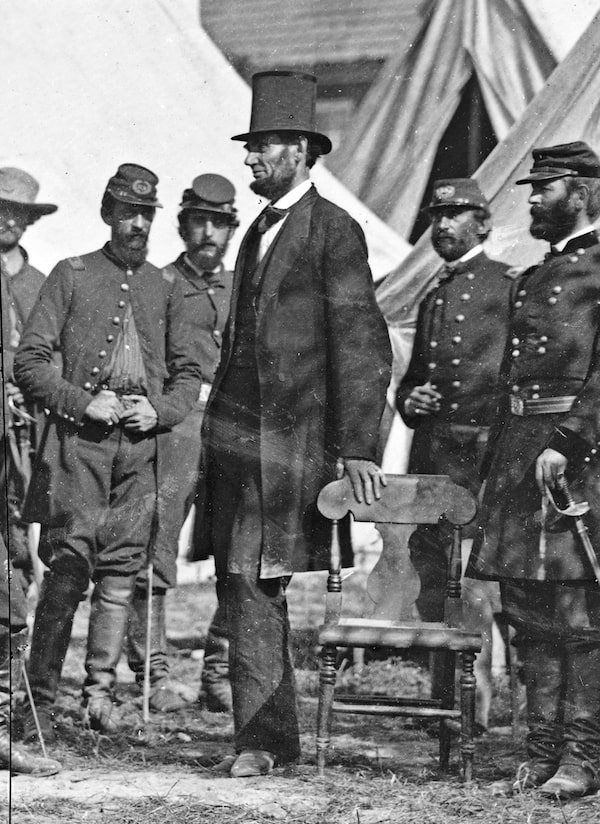

The United States’ early presidents lacked the media reach to be pastors to the nation. Lincoln performed that task on a one-on-one basis, so much so that he was known as Father Abraham, a fitting sobriquet for a leader who spoke in the rhythms of the King James Bible even though he had scant religious experience or exposure. As the end of the Civil War approached, Lincoln travelled to the Depot Field Hospital near City Point, Va. “I came here," he said, “to take by the hand the men who have achieved our glorious victories.” He did so, shaking as many as 6,000 hands. The war ended the next day. Lincoln was dead a week later.

U.S. President Abraham Lincoln with Gen. George B. McClellan and group of officers at Antietam.Library of Congress

The original modern pastoral president was Roosevelt, who, though an aristocrat, spoke the common language of Americans and expressed their hopes while comprehending their fears both in formal set-piece speeches and in his famous Fireside Chats.

“In all of the Fireside Chats, he told the people of this country that he needed them and he expressed gratitude to them," said Susan Dunn, an FDR expert and biographer at Williams College in Massachusetts. “There was real reciprocity between leader and followers in these talks. He understood that in great moments of crisis, it is essential for the country that the president be a calming influence, to be the ‘father figure’ and not a political figure, to be a trustworthy vessel. Trump doesn’t do that, and we miss that right now.”

Roosevelt’s cockiness and his cavalier approach to life and to relationships were shattered when he was beset by polio, and at Warm Springs, Ga., where he sought treatment for the disease, he took on the role of therapist and friend to his fellow victims.

It was there, Bruce Miroff of the State University of New York at Albany argues, that the future president acquired the lessons and the techniques that made him understand that, as he wrote, presidential leadership requires the ability “to educate and persuade and establish a reciprocal relationship with his or her followers” because he “understands their wants and needs, and helps them fulfill them.”

For the families of the seven, we cannot bear, as you do, the full impact of this tragedy. But we feel the loss, and we’re thinking about you so very much. Your loved ones were daring and brave, and they had that special grace, that special spirit that says, “Give me a challenge and I’ll meet it with joy.” They had a hunger to explore the universe and discover its truths. They wished to serve, and they did. They served all of us.

– Ronald Reagan after the destruction of the Challenger spacecraft, January, 1986

This sort of pastoral leadership requires special reserves of empathy. Richard Nixon lacked it; his efforts, during the Vietnam War, fell flat. Jimmy Carter, a born-again Christian who taught Sunday School and was marinated in church life, bungled it; Jon Michaels, a presidential scholar at the UCLA School of Law, said that in his famous 1979 “malaise" speech Mr. Carter “proved to be unsettling when, in at least some respects, he was well positioned to be rather pastoral."

But Mr. Reagan possessed the pastoral in surfeit.

This Jan. 28, 1986 file picture shows U.S. President Ronald Reagan in the Oval Office of the White House after a televised address to the nation about the space shuttle Challenger explosion.Dennis Cook/The Associated Press

The 40th president seldom went to church, but he once did play a chaplain in the movies. And appeared in Knute Rockne, All American, the 1940 film about the Notre Dame football coach of that name, and in that movie he played George Gipp, who urged Rockne to tell his forces to “Win one for the Gipper.”

Mr. Reagan was a natural in this, the role of a lifetime. So when, on January 28, 1986, the Challenger exploded shortly after liftoff, his delivery of the speech Peggy Noonan wrote for him was pitch-perfect. It ended with perhaps the most stirring passage in the Reagan repertoire, with an allusion to the poem High Flight by the Canadian Second World War aviator and poet John Gillespie Magee Jr.: “We will never forget them, nor the last time we saw them, this morning, as they prepared for their journey and waved goodbye and ‘slipped the surly bonds of earth’ to ‘touch the face of God.’ ”

Today our nation joins with you in grief. We mourn with you. We share your hope against hope that some may still survive.

– Bill Clinton, April, 1995, after the bombing of the federal office building in Oklahoma City

In this file photo from April 20, 1995, U.S. President Clinton and Brazilian President Fernando Cardoso (left) pause for a moment of silence for the victims of the Oklahoma City bombing during a White House welcome ceremony for Cardoso.Rick Wilking/Reuters

Today, Americans have great expectations of their president that even their most articulate predecessors – George Washington, Thomas Jefferson, Theodore Roosevelt, Woodrow Wilson – never faced. Then again, the country that modern presidents lead has a different profile in the world, and the times in which they govern have different technological and media tools.

Washington faced the challenges of leading a new, weak nation, but lacked the bullhorn, or even what Mr. Roosevelt called the “bully pulpit” that radio provided for FDR and that television provided for modern presidents. Jefferson faced grave international challenges, but could only speak in the capital and write for limited publication. Today presidents have vast audiences at their hands, as Mr. Trump has demonstrated with his 100 million or so Twitter followers.

Mr. Clinton took up the pastoral with great ease. As a boy, he went to a Billy Graham crusade with his Sunday School class; he later said “I never forgot it, and I’ve loved him ever since.” As a young man tooling around Hot Springs, Ark., in the family car, he listened to gospel music. As governor of Arkansas, he sang in the choir at Little Rock’s Immanuel Baptist Church where, as Mr. Rutherford, who has known Mr. Clinton for decades, put it, “he regularly experienced the power of prayer.” As a beleaguered president, he sought – and found – solace in the psalms. As he grew older, he told friends he wanted the Gospel song Goin’ Up Yonder ("I can take the pain, the heartache it brings”) played at his funeral. Like Lincoln, he knew the rhythms that echo off stained glass.

This is a day when all Americans from every walk of life unite in our resolve for justice and peace. America has stood down enemies before, and we will do so this time. None of us will ever forget this day, yet we go forward to defend freedom and all that is good and just in our world.

– George W. Bush, after the terrorist attacks of 9/11

Mr. Bush was roundly criticized for his invasion of Iraq and for his tax policies, and he was ridiculed for making a shambles of the English language. But his speech late in the day of the al-Qaeda attacks hit all the right notes.

“We no longer expect a president only to articulate and advance policies,” said William Howell, a presidential expert at the University of Chicago. “We expect a president to assign meaning to our identities, to channel cherished moral principles and console the country at times of great grief."

That is the political thirst that Mr. Trump tried to slake in his Oval Office remarks. His task was rendered more difficult by the unprecedented nature of the threat Americans face; his predecessors dealt with war, depression and malign terrorist attacks, and left behind a playbook for the pastoral in those eventualities. Although Mr. Obama was faced with an Ebola outbreak in 2014 (“We can beat this disease. But we have to stay vigilant”), no previous president faced a worldwide pandemic of the magnitude that Mr. Trump now confronts. It is a task complicated and compounded by his contempt for presidential conventions and expectations; indeed, he once said that being “presidential” was boring.

U.S. President Barack Obama wipes a tear as he speaks about the shooting at Sandy Hook Elementary School in Newtown, Connecticut, during a press briefing at the White House in Washington in this file photo from Dec. 14, 2012.LARRY DOWNING/Reuters

But this is a time of unusual challenge, with an entire country at risk and with the world, including Canada, facing serious health threats.

“Leaders have the capacity to calm people, and that can be essential in a health crisis,” said Jason Opal, a McGill University historian who is writing a history of epidemic diseases in the United States with his father, Steven Opal, a clinical professor of medicine at Brown University. “They can project strength and quiet fears. It’s absolutely crucial right now, where there is a situation that is grave but not yet a cause for panic.”

Keep your Opinions sharp and informed. Get the Opinion newsletter. Sign up today.