Illustration by George Wylesol

Brian Milner is a former senior economics writer and global markets columnist for The Globe and Mail.

If you want to start a lively and sometimes heated discussion, just ask people whether they have encountered any serious problems lately getting stuff they need.

One of my frustrated neighbours, an electrician, says he has more time to clean up his garden these days because of delays on the job caused by the scarcity and sharply rising prices of everything from cables and wiring to control panels. A lawyer who lives across the street is still waiting for the name-brand fridge he ordered and paid for in June, which was supposed to be delivered by September. Then there’s a former neighbour who is looking to renovate and furnish the condo she just bought. Don’t get her started. She has had her own trouble with appliances. Not to mention furniture, cabinet shelving, doors, paint – even a kitchen sink.

Most of us have similar tales of months-long waits, missing merchandise, delivery snafus, outright cancellations and escalating price tags. Welcome to the new age of shortages, when the world seems to be running out of just about everything, including enough workers to make, ship, store and haul the goods – and, in some parts of the world, the power to keep factories running.

The pandemic is not the only culprit, as British Columbians who have recently dealt with supply disruptions stemming from catastrophic floods can attest. But the coronavirus has exposed serious cracks in once-well-oiled global supply pipelines that played a key role in the huge expansion of world trade over the past two decades. The question is: Should we think of this as a temporary crisis that will be resolved as the system returns to something approaching normal? Or are we going to have to learn to live with chronic shortages – and the higher prices that come with them – for a lot longer than any of us would have imagined?

A gas-station sign in Abbotsford, B.C., announces flood-related rationing on Nov. 23.Jonathan Hayward/The Canadian Press

Back in March, 2020, before the first widespread lockdowns, household staples such as toilet paper, paper towels, disinfectants, bottled water, flour, pasta and just about anything in a can flew off store shelves. That panic-buying soon subsided as retailers limited customer purchases and replenished supplies. But the emptied shelves revealed how ill-prepared distribution systems were to deal with emergencies. And we would soon learn, to our dismay, that battered global supply chains lacked the resilience to cope with more serious shocks triggered by the rapid spread of the virus.

Pandemic-proofing those supply lines would have required building up inventories, developing supply and delivery alternatives and beefing up work forces, which would have jacked up costs in a system designed to pare them to the bone. And what corporation would have spent money on those things when doing so didn’t seem absolutely necessary?

What began in China as an annoying glitch when factories, processing plants and ports in stricken regions were forced to close in the early days of the pandemic would soon infect whole supply networks. Then, when manufacturers in China and southeast Asia got back to work, they couldn’t cope with the unexpected surge in demand from stir-crazy Western consumers for laptops, tablets, exercise equipment, workout apparel, lawn furniture and other items.

Now, producers face even more pressure to meet enormous pent-up demand from people emerging from the long, dark winter of COVID-19 with near-record levels of savings. Meanwhile, managers continue to wrestle with labour and power shortages, logistics headaches and the fallout from further shutdowns and cutbacks. To make matters worse, another round of COVID-19 outbreaks is now affecting important southeast Asian production hubs, including Malaysia and Vietnam.

“Looking back to the progression of the pandemic, it has been very challenging to predict demand fluctuations, and now the realized high demand … is running up against capacity constraints in production in many countries,” said Nitya Pandalai-Nayar, an assistant economics professor at the University of Texas at Austin who has examined the impact of global supply chains on national economies during the pandemic.

Illustration by George Wylesol

Labour shortages across a wide range of industries and services remain a serious impediment to resolving this mismatch between supply and demand. In Canada, a lack of workers has hampered transportation, energy and agriculture, hurt health care and other essential services and battered the restaurant industry.

The delivery end of the global supply chain is in a particular mess. Dozens of huge container ships line up for days outside jammed ports in southern China and Hong Kong waiting to pick up their loads. But they face much longer delays when they reach their destinations in the U.S. and Europe. Maersk, the Danish-based container shipping giant, has ordered some of its biggest vessels to steer clear of the main British container port of Felixstowe for the rest of the year because of an enormous backlog.

The cause is a dearth of dock workers to unload the cargo and truckers to deliver it. That’s a problem everywhere, but the situation is particularly dire in Britain. The poster child for the shortage economy is down an estimated 100,000 drivers, thanks in part to post-Brexit rule changes that convinced thousands of haulers from eastern Europe that there were easier places to ply their trade.

Maersk also warned earlier this month that the logjam was worsening at U.S. ports that handle the bulk of Asian imports. By mid-November, 71 ships were idling outside the vast terminals of Los Angeles and Long Beach, Cal., which was down slightly from the peak number but still high considering, the number was zero prior to the pandemic.

Canadian ports were in better shape, at least before the disastrous flooding and mudslides in southern British Columbia that cut off road and rail access to the vital port of Vancouver, washed out highways, destroyed bridges, disrupted food and fuel deliveries and triggered fresh regional and national supply woes that could take months to resolve. The devastation underscores the growing risks posed by extreme weather events to already vulnerable supply chains.

Meanwhile, billions of dollars worth of merchandise sits in growing stacks of steel shipping containers. And the cost of the containers has gone through the roof because there’s a shortage of them now too.

Container ships sit idle in Burrard Inlet, top, and docked at the Port of Vancouver, bottom, on Nov. 20, when closed railways and highways halted the flow of goods through Canada's largest seaport.Justin Sullivan/Getty Images

Against this backdrop, it’s not surprising that a plethora of products – including construction materials, metals, plastics, industrial equipment, fabrics, clothing, bicycles, shoes and toys – have become harder to find and more expensive to acquire. Retailers have been warning Christmas shoppers that anything not available today probably won’t show up before the new year. It’s not a marketing ploy. Even Christmas trees and their usual adornments are in short supply.

Among the toughest objects to get are those that include semiconductor chips. This is the main reason so many people have been waiting months for new kitchen and laundry appliances, and for parts for old ones. The soaring demand for electronic devices triggered a shortage of the integrated circuits that make so much of our stuff work.

Besides appliances, manufacturers have been forced to slash production of vehicles, computers, TVs, smartphones, cameras, robot vacuum cleaners, electric toothbrushes and anything else that connects to the internet. Until the shortage is resolved, cryptocurrency miners won’t be doing as much mining and automakers and parts suppliers will be cancelling more shifts.

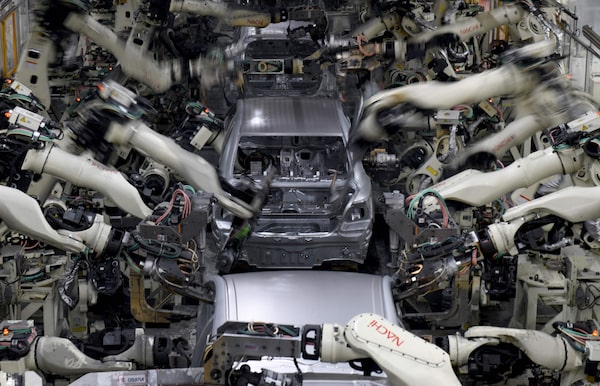

Toyota, which pretty much invented the modern supply chain as part of its drive to boost efficiency and do away with costly inventories, recognized early that these tiny chips could prove a weak link in its process. So the Japanese auto giant went against its own celebrated just-in-time manufacturing ethos and stockpiled a six-month supply at a time when rivals were cutting orders out of fear that COVID-19 would shred demand.

Unfortunately, Toyota’s cushion is long gone. And without chips, things such as steering, power windows, digital displays, various electronic safety features and entertainment units can’t work.

Toyota declared last month that “since we expect the shortage of semiconductors to continue in the long term, we will consider the use of substitutes where possible.” That could mean redesigning parts or installing some options later when chips become available.

Robot arms assemble Toyota Prius cars at the auto maker's Tsutsumi plant in Toyota City, Aichi prefecture.TOSHIFUMI KITAMURA/AFP via Getty Images

Apple, another company that has famously crafted an extensive global supply network, parcelling out manufacturing to 43 countries, blames chip shortages and other supply problems for US$6-billion in lost sales in its latest quarter. There’s little doubt that these and other global heavyweights caught flat-footed by the crisis will make the hefty investments required to shift some production closer to home, develop more diverse sources of supply for crucial pieces or at least make existing supply chains more flexible, because they can’t afford to leave the holes unplugged. So it’s entirely possible that much of the current scarcity problem will go away even if the pandemic risk remains. Perhaps all we need is a little more faith in the good old profit motive.

“It’s useful to remember that whoever is playing their role in a supply chain is not doing it for philanthropy,” said Ananth Iyer, a management professor at Purdue University in Indiana who has written several books on global supply chains, including Toyota’s. “As long as it’s in the interest of all the players to satisfy the demand, this will get resolved.”

JPMorgan Chase boss Jamie Dimon has echoed that sentiment. He told a financial conference last month that “this will not be an issue next year at all.”

For all that optimism, other forces are at play that have little to do with capitalist impulses. And they are not as easily fixed as the labour shortages, production and transportation bottlenecks and other problems triggered by the pandemic and the ensuing severe mismatch of supply and demand. The disruptors include continuing U.S.-China trade friction, heightened national security worries and intensifying pressure to decarbonize economies.

The push for cleaner power is one of the causes of the current energy crunch afflicting China, India and several European countries. And it’s triggering higher oil and gas prices everywhere. China’s energy troubles have been deepening since last spring, when Beijing’s efforts to slash dependence on coal sparked consumer electricity shortages and led local governments to shut down some heavy industrial power users. China has since lifted curbs on coal production and is boosting imports again.

In Europe, the problem is an acute shortage of natural gas, which is viewed as a cleaner transition fuel on the road from coal and oil to renewable energy sources. All this comes at a time of soaring global demand for oil. That demand is sure to keep climbing as winter approaches, and it may cause further shortages and even higher prices.

A flare burns excess natural gas in the Permian Basin in Loving County, Texas.Angus Mordant/Reuters

The impact of the energy crisis on supply lines – and the likelihood of future hiccups – is yet another headache for the global players trying to stabilize their networks.

But not all of the disruptive forces threatening global trade are related to resources or labour. There’s also rising protectionism.

Before the pandemic struck, Washington and its allies had already embarked on efforts to rein in China’s widening geopolitical ambitions and safeguard their own economic and national security interests by bringing more production home and developing other sources of supply.

The goal is to reduce China’s clout stemming from its critical role at the centre of the supply spider webs – even clothing made in Vietnam typically comes from Chinese-owned companies – and its domination of certain essential new-economy resources and materials, such as cobalt, rare-earth minerals and magnesium.

China is the world’s dominant processor of the rare-earth elements used in electric vehicle batteries, wind turbines, fibre optics, advanced ceramics, lasers and sensitive military hardware, such as jet engines and missile guidance systems.

Beijing has already shown a willingness to use this near-monopoly for political purposes, blocking exports of those materials to Japan for two months in 2010 over a fishing dispute. The threat of imposed shortages briefly sent prices skyrocketing and persuaded Tokyo that it had better develop other sources.

A worker tends to a blast furnace at ThyssenKrupp AG's steelworks in Duisburg, Germany.Ina Fassbender/Reuters

Now, something similar is happening with magnesium – another crucial, though far from rare, manufacturing material. China accounts for more than 85 per cent of the world’s processed magnesium, which hardens aluminum alloys used in auto parts, construction materials and packaging. But nearly three dozen of the country’s heavily polluting processing plants have been forced to close as a result of electricity shortages, and those still operating have had to reduce output.

European industry, which depends on China for all but about 5 per cent of its magnesium needs, has pushed the panic button. “Without urgent action by the European Union, this issue, if not resolved, threatens thousands of businesses across Europe, their entire supply chains and the millions of jobs that rely on them,” a dozen lobby groups warned in a joint letter. There are no substitutes, and existing supplies will run out by the end of November, they said.

Volkswagen, BMW and other European car makers have already been forced to cut production because of the chip shortage. Wait until they can’t get hold of steering columns, gearboxes, seat frames and other parts made of lightweight sheet metal.

Europe hasn’t had any domestic magnesium production since the last supplier was driven out of business 20 years ago by cheap Chinese competition. U.S. car makers have largely been spared this particular shortage, because they get most of what they need from an American plant and the rest from suppliers in Canada, Israel and Mexico. They don’t have much choice. U.S. tariffs exceeding 140 per cent have kept out Chinese suppliers.

Some observers argue that entire supply chains ought to work this way, with a regional rather than a global footprint – a shift that would be particularly beneficial to Canada. Prime Minister Justin Trudeau has made this case to U.S. President Joe Biden, citing the efficiency of the North American auto industry and reminding him that Canada produces 13 of the 35 minerals the U.S. regards as essential to its security.

Prime Minister Justin Trudeau, left, joins the U.S. and Mexican presidents in Washington on Nov. 18.Susan Walsh/The Associated Press

Washington has made it clear that it views dependence on any product largely controlled by an undemocratic country as a supply-chain risk. The fallout from COVID-19 and the deepening climate crisis have only added to the urgency of doing something about it.

“From a policy perspective, we are likely to see the U.S. and other countries take measures that meet multiple objectives, such as bringing production facilities back onshore, decoupling from China and plugging national security vulnerabilities,” said Eswar Prasad, a professor of trade policy at Cornell University and a former head of the International Monetary Fund’s China division. “The rising tensions with China and the disruption of cross-border supply chains provide a useful opportunity for the [Biden] administration to promote such initiatives that aim at rebuilding U.S. capacity in critical areas.”

That’s why new semiconductor plants are coming fast in the U.S., Japan, Europe and China, as governments vow never to be caught chipless again. Each new facility costs billions. But if governments are willing to dish out hefty subsidies in the name of national security, suppliers like Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Co., the largest contract chip maker in the world, will be happy to take their money in exchange for sharing expertise. The eventual result is sure to be a huge oversupply and collapsing prices.

But while we wait for capitalism to do its thing and for companies to figure out how to reassemble the pieces of their manufacturing puzzles, us lowly consumers will have to learn to live with at least modest shortages for some time, and higher prices for just about everything.

As geopolitical strategist Marko Papic reminded me, “It’s not the end of the world if things take longer to get and they’re more expensive. We’ll adjust to that, as we have to dealing with the pandemic.”

Try telling that to my neighbours.

Supply chains and you: More from The Globe and Mail

Watch: Personal finance columnist Rob Carrick answers questions about some of the factors driving inflation and how people can reduce its impact on their household budget.

Food inflation is the next big threat to Canadians’ finances

Canadian retailers take to the skies to mitigate holiday supply chain woes

Why Canadian auto production is getting hit especially hard

Supply chains are still a mess – and the Delta variant is making things worse

Keep your Opinions sharp and informed. Get the Opinion newsletter. Sign up today.