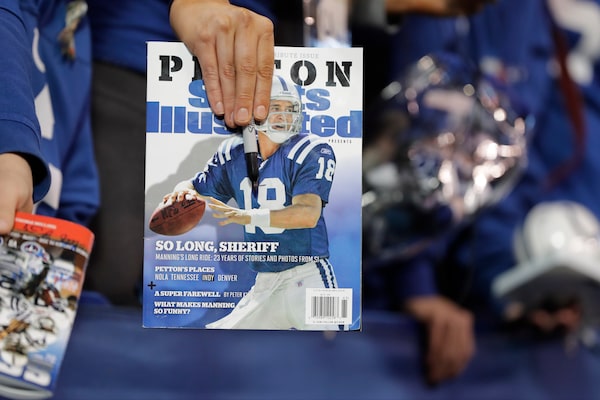

A fan waits for former Indianapolis Colts quarterback Peyton Manning to sign autographs before a game between the Tennessee Titans and the Colts, on Nov. 20, 2016.Darron Cummings/The Associated Press

Brett Popplewell is an associate professor of journalism at Carleton University and the author of Outsider: An Old Man, a Mountain and the Search for a Hidden Past. His writing has appeared in The Best American Sports Writing and The Best Canadian Essays.

There’s a quote I have canned in my mind and ready to share whenever someone asks what it is I do as a magazine writer. But before I share it here, please know that I cribbed it from ESPN’s Wright Thompson, who I heard say it on a public stage in Dallas in 2017, where he admitted to the gathered crowd that he, too, had repurposed it from Gary Smith.

Mr. Smith, of Sports Illustrated fame, is among the most decorated magazine writers to ever live, heir to the lyrical thrones of George Plimpton and Mark Kram – great names in a long line of sportswriters. Ghosts without equals in the modern press box.

Having retired from Sports Illustrated 11 years ago, Mr. Smith now teaches mindfulness to elementary school students in Charleston, S.C. It’s a fitting twilight for the sportswriter whose work required a degree of concentration, presence and engagement from readers that is increasingly hard to come by these days.

All we do as writers, Mr. Smith is said to have said, is figure out the central complication in someone’s life and how, on a daily basis, they go about solving it.

For decades, Mr. Smith’s adherence to that mantra led his journalism to transcend the realm of sport. With each story he wrote he exposed universal truths in the everyday struggles between victory and defeat, tension and perseverance. The tales he told took months to report and just as long to write. He averaged four stories a year, which is not very many when you’re employed by a magazine that comes out every week. But for the editors at Sports Illustrated, Mr. Smith’s stories were investments in a style of journalism that set their magazine apart in an increasingly crowded mediascape.

Founded in 1954, Sports Illustrated was, for most of its 70-year run, the most recognizable and respected brand in sports media. The world’s biggest athletes aspired to be in its pages, as did many of the biggest names in 20th-century American literature. Though most of the writers the magazine initially hired came from a similar demographic, they worked together to create a product that had unexpected literary chops. John Steinbeck wrote about fishing in Year 1. Nobel laureate William Faulkner covered a clash between the New York Rangers and Montreal Canadiens in Year 2. In 1956, the magazine hired poet Robert Frost to cover the MLB All-Star game.

To someone who never really leafed through the magazine, Sports Illustrated may have seemed little more than a weekly mailout of sports minutiae. But those who sat down and read it every week found epic narratives inside. Memorable stories of false gods, fallen idols and human suffering juxtaposed against sporting triumph (see Mark Kram’s biblical account of the Thrilla in Manila, Oct. 12, 1975).

The magazine itself was so highly regarded as an editorial package that even my Grade 10 English teacher suggested we read it when we were done studying Shakespeare. She circulated one of George Plimpton’s articles in our class to show us why. She used it to highlight how you could find dramatic literature and modern poetry even where you least expect.

The Sports Illustrated I was introduced to in that classroom was robust. And though it has lost many of its readers and much of its journalistic clout in the 25 years since, it remained one of few magazines that could still generate significant attention for a person, issue or cause when it chose to include them – especially on its cover. In recent years, the magazine appeared to be taking strides to increase diversity in its makeup and coverage. But it still had glaring inequities at its core. As Zoe Williams of The Guardian put it last year, “Let’s not waste indignation on the fact that men were lauded by Sports Illustrated for what they could do, while women were prized for what they looked like.”

In 2021, the magazine made headlines when a transgender model posed for the cover of that year’s swimsuit issue. Some championed the publication for the inclusive move, others labelled it “inclusive objectification.” In 2023, it made waves again when Martha Stewart, at age 81, became the oldest model to appear on the swimsuit issue’s cover. It now appears Ms. Stewart may be the last person who will ever be a Sports Illustrated swimsuit cover model.

As of Jan. 19, the central complication in the life of Sports Illustrated has become existential. The apparent solution from the magazine’s owners: kill the brand. Almost all of the magazine’s staff were recently laid off. It’s currently unclear whether the title is officially dead or if it will continue in some zombie-like state for a few more issues.

I recognize that in 2024, the death of a 70-year-old printed magazine is of diminishing public interest. Magazines are old-fashioned by nature, and the swimsuit issue is an anachronism unto itself. But the demise of Sports Illustrated is worth a collective pause, because the type of journalism that magazine was once known for is becoming increasingly hard to find. And though you can sometimes get whiffs of it in modern digital publications such as The Athletic, something has been lost.

It’s no secret that magazines are dying. The New York Times essentially wrote an obit for the entire industry seven years ago, declaring the end of a century’s worth of journalistic tradition in which these glossy tomes actually mattered. It’s a harsh narrative that I know well. Ten years ago I was a senior writer with Sportsnet magazine, a short-lived title that tried to compete with Sports Illustrated in Canada. It was the most imaginative place I’ve ever worked and when it died, nothing in this country really replaced it.

As I reflect on that reality, I have to admit I understand why Sports Illustrated and other titles are disappearing. Like many who have been saddened by the magazine’s demise, it’s been a long time since I picked up an issue.