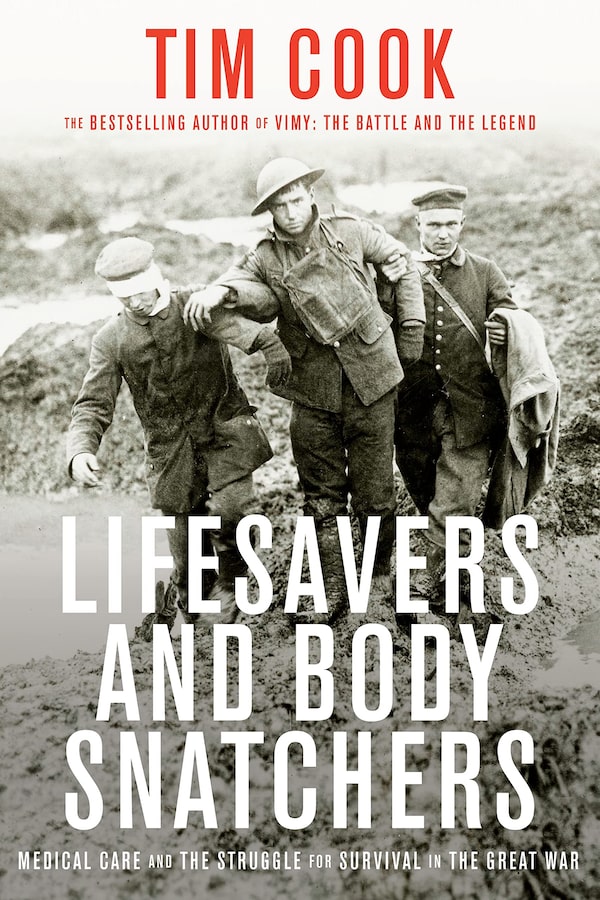

“Four stretcher-bearers and three replacements carry a wounded man through the shattered Passchendaele landscape.”Four stretcher-bearers and three replacements carry a wounded man through the shattered Passchendaele landscape./CEF official photograph

Tim Cook’s most recent book is Lifesavers and Body Snatchers: Medical Care and the Struggle for Survival in the Great War.

When I was diagnosed with Hodgkin’s lymphoma cancer in 2012 at the age of 40, I was told to down tools and concentrate on my health. It seemed like good advice, so I did just that. I stopped writing and instead focused on being well. I did some yoga. I tried breathing exercises. I practised mindfulness. I sent mantras out into the universe.

After a short period, I went back to research and writing, something I had been doing for almost 20 years as a public historian. I had concluded that cancer takes and takes, often until there is nothing left. I did not want it to extinguish the writer in me.

So I researched, and read and wrote as I was being poisoned and irradiated, losing myself in the past to give myself a future. Over a two-year ordeal that included multiple rounds of chemotherapy and radiation, and two stem-cell transplants, the cancer was destroyed.

During this test, as I read history books in the cancer ward in preparation for a two-volume history of Canada and the Second World War, I found that many of my oncologists at the General Hospital in Ottawa were not only interested in my research, but they had their own stories about medical practices that came about during wartime. Memorably, one doctor gave me an impromptu lecture on how mustard gas in the Great War had led to the development of certain chemotherapies. I was both fascinated and horrified.

I was also intrigued that so many medical practitioners saw themselves as part of a long continuum of caregivers, and I thought, in a vague way, that it might be nice to write a book about military medicine and one day present it to some of the doctors and nurses as a gesture of thanks. But I had other books to write, and it was not until 2020 that I returned to the subject of military medicine.

Lifesavers and Body Snatchers: Medical Care and the Struggle for Survival in the Great War, by Tim CookHandout

All books have their own history, and my latest history book is no different. I started what would become Lifesavers and Body Snatchers: Medical Care and the Struggle for Survival in the Great War in April, 2020. While research takes us into many unexpected places, I began with the devastating pandemic of 1918 to 1920, and how Canadians dealt with the invisible death 100 years ago.

How could I not as everyone was living through, and struggling with, the current pandemic that was sweeping the globe? The virus from 1918 to 1920 killed about 55,000 Canadians but had been largely forgotten until we faced our own iteration of this life-changing crisis. It was a topic worthy of study.

And yet the medical battles of the Great War went far beyond the virus – and Canadian doctors and nurses played a crucial role in the terrible attritional war of 1914 to 1918. Half of all Canadian doctors and a third of the country’s nurses served in uniform, caring for the 620,000 Canadians who also left their loved ones to fight against the Kaiser’s forces.

So many medical practitioners were drawn into the vortex that Canadians at home suffered shortages of doctors by the midpoint of the war – an “intolerable” doctor famine, as it was labelled in one medical journal. There was talk of conscripting doctors for service in Canada and redistributing them against their will across the nation. It did not happen, but the situation was desperate as the war overseas drew in medical personnel like a sucking chest wound.

And we needed every single one of them. Throughout centuries of warfare, almost every army saw more soldiers die from bacteria and viruses than from bullets and shells. During the Great War, doctors helped keep the fighting forces from withering away from disease and illness, a crucial act of “force protection” as thousands of Canadians fought amid the slurry of mud and filth in Western Front trenches populated with rats and rotting corpses.

Doctors impressed on the military high command the need to instigate mandatory vaccines against smallpox and typhoid. These vaccinations saved lives. The British, who initially had a voluntary system of vaccination, suffered comparatively more losses to disease. As a Canadian doctor wrote of those soldiers who refused vaccination and were removed from service: “He was not allowed to endanger the health of his comrades.”

Several thousand Canadians still died from disease in the putrid mire, but the great killer during the war was the devastating effects from artillery, machine guns, rifles, mortars and chemical weapons.

“Canadian surgical team of two nurses, a surgeon, and an anesthetist work on a wounded soldier from the Battle of the Somme”Canadian surgical team of two nurses, a surgeon, and an anesthetist work on a wounded soldier from the Battle of the Somme/Courtesy of Tim Cook

A Canadian doctor, Lieutenant-Colonel Walter Langmuir Watt, wrote of the carnage: “Wounds here, wounds there, wounds everywhere. Legs, feet, hands missing; bleeding stumps controlled by rough field tourniquets, large portions of the abdominal walls shot away; faces horribly mutilated; bones shattered to pieces; holes that you could put your clenched fist into, filled with dirt and mud, bits of equipment and clothing, until it all became like a hideous nightmare.”

To meet the horror, doctors devised new surgical treatments. The nefarious effects of infection that seethed in most wounds killed countless thousands in the age before antibiotics, with French, British, German and all other surgeons experimenting with means to eradicate the infections. A solution was to remove great swaths of flesh from ripped-open bodies, hoping to cut out the infection, while irrigating wounds with saline and chemical solutions.

If that did not work, amputation was often the only alternative. Colonel J.M. Elder, a prewar surgeon in Montreal, noted that he and other doctors overseas struggled to strike a “just balance between the saving of a limb and the saving of a life.”

Nine out of 10 wounded Canadians who reached a surgeon survived. Obscured in those statistics are the many tens of thousands of wounded who died in a smoking shell crater or disappeared into the mud of the many battlefields, dying alone and in agony.

To save lives required a constant learning process. When a study revealed soldiers dying of shock, doctors experimented with blood transfusions, with Canadian practitioners acting as pioneers among the Allied forces. By 1918, the last year of war, it was common to infuse the grievously wounded, in patient-to-patient transfers of life-giving blood.

X-rays were used extensively for the first time in war, assisting surgeons as they navigated the savagely pulped organs peppered with metal and shattered bones.

Invisible wounds to the mind, labelled broadly as shell shock, were particularly troubling to the high command that watched with concern as soldiers broke under the strain. The medical services were ordered to reduce losses and return soldiers to the front. New psychiatric approaches, including rest and talk therapy were mixed with electric shock therapy.

As I research and wrote the book, reading about our contemporary caregivers within the hard-pressed medical system in Canada, I was more aware of the emotional burden that lay heavy on the nurses and doctors of the Great War.

“I am witnessing terrible suffering,” wrote nursing sister Sophie Hoerner of the patients in her Canadian hospital behind the Western Front. Nursing sister Elizabeth Paynter recounted the agony of administering care to young men with terrible wounds, hoping they would recover: “Another patient died, and another still was very low, while there were at least four other delirious head cases, who seemed to take turns pulling off their dressings or getting out of bed.”

Other nurses wrote last letters to next of kin, telling them of a son, father or husband who would not be returning home, seeking to soften the blow with a personalized note or in sharing a last sentiment.

How could one read of the nurses who held the hands of young Canadian soldiers whispering for their mothers as they breathed their last breath and not weep from thinking about what was happening in our COVID-19 wards – patients dying without their loved ones, usually with only nurses and doctors to bear witness?

Through 2020 and early 2021, writing history that was connected to the contemporary medical crisis kept me going, a shield against the sheer awfulness of COVID with its physical threat and mental attrition that seemed to have no end.

Of course, for the generation that lived through the Great War, they too could see no end to the slaughter. They too believed it would be a forever war.

But the guns finally went silent on Nov. 11, 1918, and, like all great catastrophes, there were powerful legacies. In the field of medicine, as thousands of doctors and nurses returned to their communities, battlefield innovations were mapped on to civilian care.

X-rays were employed to assist those with tuberculosis, the great killer of Canadians aged 18 to 45 in the early 20th century.

Blood transfusions saved lives, with pioneers like Lawrence Bruce Robertson taking the lessons of infusing dying soldiers on the Somme to assist burn patients at Toronto’s Hospital for Sick Children.

To engage more fully in preventative care, a new Department of Health was created in 1919. It aligned with the desire of Canadians and medical practitioners to prevent disease instead of simply treating it. The success of soldiers’ wartime vaccinations in reducing losses to disease and the revelations of the poor health of tens of thousands of malnourished men turned away from service further drove the need for change.

“There is nothing like a war to discover the steps that should be taken for the protection of public health,” mused one influential Canadian senator.

There were advances in physiotherapy for the thousands of veterans who were grievously wounded, developments in psychology (although treatment remained deeply contested), and even a new emphasis on maternal care with the message of needing to save the lives of babies to replace the 66,000 Canadian soldiers killed during the war. In Montreal at the turn of the century, for instance, one in four babies had died before their first birthday, a horrendous indictment of the lack of public health in Canada.

“Out of the welter of this terrible war,” wrote one Canadian physician, “with all its misery and suffering, will emerge as some small measure of compensation a fuller knowledge of the prevention of disease, the treatment and cure of sickness and wounds and general surgical conditions, which knowledge will be used by the medical profession to the great benefit of living humanity and generations yet unborn.”

Lifesavers and Body Snatchers is not about our current pandemic, but, as with most history books, the present bleeds into its pages.

I was excited about a book tour in September to speak about my findings and to hear the reaction from readers. Those plans were laid to waste when cancer struck again.

It is a different cancer than 10 years ago. And after a brief pity party, I prepared for battle. I told myself that I was, perhaps, better equipped than some for the trial ahead, a veteran of past fights and grounded in the long view provided by history.

I marched forward, head down, hoping to make the hard yards. The battle plan saw radiation and chemo in the summer, and then surgery some time in September.

I met daily the doctors and nurses who treated me with care, compassion and skill. Some were interested in the new book; others looked too harried to have much time to read. I hope they do. There are lessons from the Great War on what nurses and doctors did in a time of great crisis and mass death, with no end in sight for those caught in the storm. It might bring some comfort to those medical workers today as our health care system is on the brink of breaking under unyielding strain.

For me, I hope to survive and be on the road again talking about my work. In the meantime, I will keep writing to cope and endure, and to find meaning in the past to provide guidance in the present, and some hope for the future.

Keep your Opinions sharp and informed. Get the Opinion newsletter. Sign up today.