Rob Sargeant sits alongside wife Karen and sons Matthew and David at San Diego's Petco Park this past September, 10 months after he was diagnosed with a terminal brain tumour. Rob and David, avid baseball fans, enjoyed seeing a game here and at Dodger Stadium on what would be the family's last vacation together.Family photos courtesy of Karen Sargeant

Jillian Horton is a physician and the author of the national bestseller We Are All Perfectly Fine: A Memoir of Love, Medicine and Healing.

I first met Rob Sargeant 20 years ago, when we were residents in the internal medicine program at the University of Toronto. He was already a force of nature: Fresh out of medical school, he was happily married to his sweetheart, Karen – a partner at a Bay Street law firm – and raising the first of his two sons. Like our classmates, we were driven and intense, pushing ourselves to inhuman limits, planning for bright futures.

But even in that field of highly accomplished people, Rob – or “Sarge,” as most people called him – stood out. There was something about him I admired, maybe even envied.

He was funny in a dry, Jon Stewart-esque way. He had a better repertoire of swear words than I did. He was confident but never arrogant. And he exuded the uncomplicated joy of a person doing something he loved in a place where he belonged.

The four years of our fellowship training passed quickly, and when it was over, Rob took a staff job at St. Michael’s Hospital, a place we both adored. I, on the other hand, had another calling afterward: my husband and I packed our things into a U-Haul, and I said tearful goodbyes to Toronto and my friends there. It was time for me to go home to Winnipeg, where, just a few hours’ drive away, my family was slowly imploding.

My oldest sister, Wendy, suffered a brain tumour at a young age, and had been left permanently and profoundly disabled. Her life had been one long, drawn-out tragedy – first, there was the tumour that torched her future and scorched her life to the ground, and then there were all the years after, when that tumour’s endless complications slowly took her personhood away. And yet, she remained a hilarious and spirited person, one who mourned her deep losses but also dwelled in acceptance.

I went into medicine because of Wendy. Her experiences with the medical system had often been cold and uncaring, and I wanted to correct that by teaching student doctors – I saw it as a powerful way to channel my anger at her mistreatment and to positively shape the behaviour of future generations of doctors.

After a life of suffering, Wendy died in her sleep in 2015. So I’d long harboured a special hatred for brain tumours and their ghastly consequences. Their brutal insults always felt personal to me.

Perhaps that is another reason why last year, more than a decade after I left my friends from residency behind in Toronto, an out-of-the-blue message shook me to the core. A beloved mentor whom Rob and I shared sent me a text – the first of many I’d receive over the next year that would rattle me as both a doctor and a human being.

Rob had a brain tumour. But even worse: It was inoperable. The Sarge had a terminal disease.

Dr. Sargeant in the spring of 2021 with change nurse Maria Hernandez.

In the years after I left Toronto, Rob and I both became career medical educators – I, as an associate dean at the University of Manitoba, and he as section head of Internal Medicine at St. Michael’s. We’d see each other at the occasional conference, and were in touch a handful of times a year.

I joked that I was Rob’s talent pipeline because I would send my best medical students his way, and when they came home, they would always regale me with stories about Rob: his brilliance, his sense of humour, and his legendary “fluid and electrolyte” rounds – medical code for beers after work. My thank-you e-mail chains with Rob were always peppered with copious swears and fond recollections of people who’d taught us to practice our craft with skill and care. We’d been buddies in bad times – they were the origin of our bond – and so ours was a shared language, which gave life to memories I thought we’d have years to parse.

Then, in the thick of the COVID-19 pandemic, Rob started experiencing “foot drop”– a condition in which the toes drag on the ground when walking. It was a Friday morning when a physician friend saw him walking abnormally from a distance in the hall; he pulled Rob aside and murmured that he’d meet him in his office in 20 minutes.

There, he found red flags on Rob’s physical exam – his reflexes on the side of his dragging foot were too vigorous, a sign that localized the problem to his brain or spinal cord and not the less worrisome peripheral nervous system. The doctor ordered an urgent MRI, persuading the radiologist to squeeze Rob in that night.

Rob was the attending physician on the internal medicine unit that week. So that day, in vintage form, he carried on with his work until it was time to go down to the scanner and present himself – not as a physician, but as a patient.

When the scan was finished, Rob got dressed and passed by the radiology reading room on his way back to check on his ward patients. But then, he spotted his colleague who had organized the MRI, sitting alongside the radiologist and staring intently at the computer screen. Rob’s colleague wasn’t supposed to be at the hospital – he’d said he would be at home and would phone him later with results – but the radiologist had called Rob’s doctor back to the hospital while Rob was still on the table in his gown. The scanner had generated a sequence of images of a dark, shadowy mass in a place deep inside their friend and colleague’s brain, as frightening as a hand grenade, sitting where no surgical instruments could reach.

Jillian Horton.Leif Norman

How many times had Rob and I been the messengers of terrible results like that? Hundreds. Thousands. We were experts at giving that news.

We liked it to unfold as a controlled explosion. We didn’t want our patients to see us whispering to the oncologist in the hall with unmistakable grim looks on our faces. Everybody knows what is about to happen when they see those looks, and so you try to set the stage to say the right words at the right time, in a quiet space or a private room. But in another sense, there is no right time to learn you have a brain tumour, no right time to see the traces of tears in your colleague’s eyes as they utter words you yourself have only ever delivered and not received. Being on the receiving end of those words – that was a new skill for Rob, unwanted, uncharted.

I wrote to him as soon as I found out. I told him how profoundly sorry I was; I told him I couldn’t stop thinking about him, since I found out the worst news I’d heard that year, which was really saying something. I sent him my thoughts, my fandom, my props, my love, my solidarity, and a piece I had written about my family’s personal window into his special hell. I sent him swear words, as was our norm, but this time, they were deployed out of anger. Despite all my years of being a doctor, it was all I could think of to do.

I was surprised to see his reply pop up in my inbox just a few hours later.

“Thank you very much for this Jill – and for sharing you own personal journey with this wretched disease,” he said. “I’m still navigating my approach to all of this, but so far your prior piece and this email rings true.

“I’m so grateful that you reached out to me. ‘Old’ friends are often the best friends.”

Rob Sargeant chats with an elderly patient in Toronto in 1999, his fourth year of medical school.

In the days that followed, I couldn’t get Rob off my mind. I teared up thinking back to our youthful bravado as we used to roam the hospital halls as residents, as if our patients were firmly ensconced on the other side of a sorting line, assuming for the sake of self-preservation that our health, as doctors, was any different, somehow more dependable than theirs.

I couldn’t stop picturing him coming out of that CT scanner at St. Michael’s, seeing his two colleagues sitting in the dim light of the monitors, their faces etched with the awful news he then immediately surmised.

But my continued conversations with him left me with plenty more to consider.

“Just letting my old buddy know you’re on my mind so often these days,” I wrote to him, about a week later.

“Thanks Jill,” he replied. “I really do feel the love and support. I’m hanging in. Have you noticed recently how beautiful a sunrise can be? My new hospital bed is in an alcove in our home and the world comes to life around me. Amazing. I missed a ton of shit by just focusing on work all of the time.

“Steady on.”

What he’d missed because of work – those words burrowed into my head. They pierced something raw inside of me, the memory of a pile-up of years when the kids were small and the hospital always seemed to get dibs on our time. What exactly did we trade it all for?

Our work, it turns out, is also progressive, metastatic, terminal. It stalks us even when we go on vacation. It intruded on bath times and bedtimes and snack times and family time. Work is our privilege, but also our master – maybe even our addiction, if we’re being honest. We always seemed to give it the best parts of us.

What did we subsidize it with? Where were we for the sunrises?

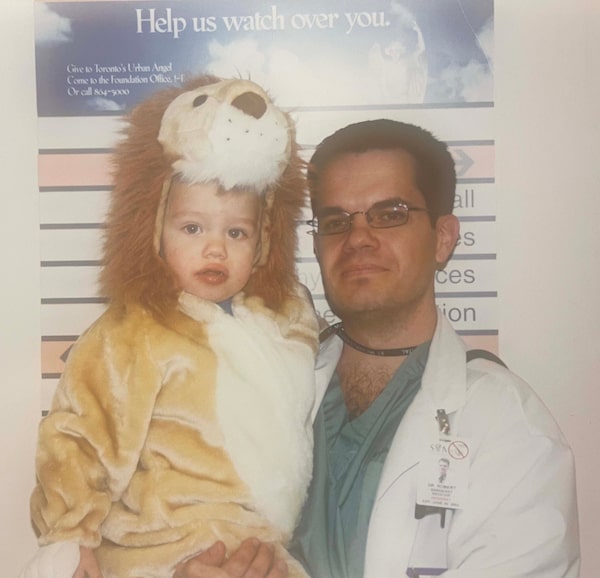

A young Matthew Sargeant, dressed as a lion for Halloween in 2000, spends time with his father.

When you are a doctor and a colleague is sick, there is an intolerable urge to do. Rob’s cancer is called a glioblastoma multiforme, a type of brain tumour that invokes a reflexive cringe from any physician because it is so notoriously difficult to manage. I found myself fantasizing about using my connections in the U.S. to help locate someone, anyone, who could operate on him. But it was delusional, a kind of magical thinking. We had all the same connections. People who were more powerful than me were already looking to move mountains for him, but in the end it didn’t matter, because a mountain is no match for an asteroid.

I became consumed with one question: What could I do that wouldn’t be redundant or maudlin? Then it dawned on me: I could create.

The Royal College of Physicians and Surgeons of Canada had just recruited me to lead a series highlighting the work of its members. And I realized I could interview Rob, to leave a permanent love letter for his family, friends and the generations of students he had taught. The CEO of the organization embraced the idea immediately, and Rob and his wife Karen agreed as well. So in a matter of a few days, I’d booked a ticket, found the perfect cameraman, and was preparing for a journey back to Toronto to see my old friend.

But I didn’t want to talk to Rob about his death. I wanted to talk about his wild, oversized, big-hearted, swear-filled life. So in the middle of packing my suitcase, I e-mailed my friend, Harvey Chochinov, a psychiatrist known around the world for his work on what he has coined “Dignity Therapy.” I wanted to tease things out from Rob that I don’t always talk about with my critically ill patients in the hospital, and so I asked Harvey for his advice. He sent me a list of questions that form the backbone of his work: Are there specific things that you would want your family to know about you, and are there particular things you would want them to remember? What have you learned about life that you would want to pass along to others? In creating this permanent record, are there other things that you would like included?

“Dignity therapy is a way of helping people create their own legacy, shaping how others will remember them,” Harvey told me recently. “It’s been shown to enhance end-of-life experience.”

How I hated thinking of the words “end-of life” in the context of Rob. But these were the questions I needed to ask if I was going to do justice to Rob’s legacy. And I was determined to do just that.

The Sargeants outside their home in the spring of 2021, when one of Karen's colleagues organized a 'Walk for Rob' whose small admission fees went to charities of the donors' choice.

I flew east to Toronto, back to our old stomping grounds, my first time outside of Manitoba since the start of the pandemic. I arrived at Rob and Karen’s house in midtown Toronto on a Tuesday morning after a fitful sleep at a downtown hotel.

Their son Matthew let me into the house. Rob was behind him, just out of sight in the alcove where they had set up his hospital bed, the one where he watched the sunrise. Matthew excused himself to help his Dad, and a few minutes later, with his son pushing his wheelchair, my old friend emerged. My eyes filled with tears as we embraced. His face was rounded from high-dose steroids, but I was inexplicably relieved to see that his grin was unmistakably that of the same old Sarge.

That afternoon, with the cameras rolling, Rob and I explored the deeper lessons of his life. There were multiple recurring themes – humility, perseverance, legacy – and his humour was sharp and irrepressible. He told me the story of his illness, nestling it in a much bigger picture; we talked a lot about how much meaning he has found in his life as a teacher. He came back again and again to his deep well of gratitude – for the people who were caring for him, for the expressions of love from his students over the years, for his family, for his career and life in medicine. We recorded for more than an hour, our conversation periodically punctuated by his left hand’s subtle epileptic seizures, which he endured without complaint.

At the end of the afternoon, he was spent – chemotherapy often siphons off most of a person’s energy – and I wanted to let him rest. But I did not want to say goodbye. We shared a long hug, shedding a few more tears. Then, as I lingered briefly at the door, we promised each other we’d see each other again soon.

It was a hot day in June, and I decided impulsively to walk back to the hotel, a straight-line trek of several kilometres south toward Toronto’s waterfront. As I passed each subway stop and neighbourhood, I found myself overcome by memories of the Toronto of my youth and the times I spent with Rob and our many classmates. I thought about the irony of walking down Yonge Street while no longer young.

After an hour or so, it dawned on me that by coincidence, my route was taking me past Mount Pleasant Cemetery, where Rob told me he’d taken his family a few weeks ago to choose his burial plot. When I lived in Toronto, Mount Pleasant had only ever been an idea to me, a rapid sequence of images flashing through windows between subway stations, like a stop-motion animation; sometimes our patients would be buried there, but we’d always feel like it had nothing to do with us. Now, as I walked past its stone archway and weeping willows, it was suddenly, indisputably relevant, our mortality unmistakably real.

A song popped into my mind: Rufus Wainwright’s In A Graveyard, which was released in 2001, the same year Rob and I were interns. Back then, I had that song on perpetual repeat sometimes listening in the dark with tears of anguish staining my cheeks, surrounded by so much suffering and death at the hospital, and overwhelmed by the same powerlessness I now felt about my friend.

Wandering properties of death ... Worldly boundaries of dying Were for just a moment never ours

Twenty years. How could 20 years have passed? Twenty years is the time it takes for many of us to really reach our academic prime. We produce our best work. We hit our life’s stride. We become experts in our field. We finally develop as much wisdom as knowledge. I wanted Rob to enjoy this phase and the ripe fruits of his labour, to see everything he had grown from seed.

But Rob won’t get to see it all. Many of our teachers never do.

Dr. Sargeant at a St. Michael's Hospital nurses station in 2016 or 2017.

In medicine, the Hippocratic oath is sacred. The fundamental promise associated with it is well-known – first, do no harm – but the full ancient Greek medical text is long, and has many more directives.

In particular, it makes special note of our relationship with our teachers. It asks us “to hold him who has taught me this art as equal to my parents and to live my life in partnership with him.” Those relationships – medicine’s sisterhood and brotherhood – are one of the true highlights of the profession. The oath reminds us that we are part of a chain of learning, one that stretches back to Aristotle and reaches forward until the end of time. Part of that deal is, therefore, that we do not get to meet all the generations we influence or who influenced us.

But even if we never get close enough to see their faces, we know they are there. And Rob can at least see their shapes off in the distance, see how many of them are applauding and holding their brilliant, humble, curse-filled teacher in their hearts.

The Sarge has had a very hard year. I hope he gets see these words in print, and all the words of support and love I know that it will prompt. Because yes, he was right, he missed so much because of work. But look what he accomplished through it. What a difference he made to the world through his offering.

We cannot escape the worldly boundaries of dying. But maybe – in addition to our children – there are a handful of ways we can live on. Maybe one way is through the eyes of a friend, who will remember us with every sunrise for the rest of their life.

And maybe another one is teaching.

Editor’s note (Nov. 29, 2021): Dr. Rob Sargeant passed away on Nov. 28.

Keep your Opinions sharp and informed. Get the Opinion newsletter. Sign up today.