Searchers look for clandestine graves in the mountains surrounding Iguala, where the disappearance of 43 students in 2014 rocked Mexico and shook the world.

Photography by Brett Gundlock/Boreal Collective for The Globe and Mail

There was a moment, well into the still heat of mid-morning, when one of the searchers found something: a crumpled sleeve crusted in the earth. She gave a shout, and began to gouge at it with the stick she carried, until she could lift the stained half of a pale cotton jacket from the ground.

At her shout, the others hastened toward her through the thorny brush, and they, too, began to poke at the ground.

On their faces, a war of emotions:

Please let us find something.

Please let it be him.

Please, please, don't let it be him.

There was, in the end, a pair of pants, some socks, a T-shirt, loosely covered in dirt.

No body. No one with the clothes.

The families melted back into the bush, and began to search some more.

This ritual, some version of it, plays out every Sunday morning in the scrubby hills around the town of Iguala, about a three-hour drive south of the Mexican capital. Families gather at the rough cinderblock Church of San Gerardo, and pile into a couple of old trucks. They wait for their security escort – a truckload of federal police – and then head into the hills.

There are a few children; most of the searchers are parents, with faces decades older than their years.

People have been going missing in Iguala for a long time. And everyone knows that bodies are dumped in the hills. But until a year and a half ago, nobody looked in these hills; they didn't dare.

Then came the events of Sept. 26, 2014. That day, a group of about 100 students from the Ayotzinapa Rural Teachers' College, an all-male school serving mostly low-income and indigenous students, set out from their campus in the hills outside Iguala to commandeer some buses. Ayotzinapa students had a history of left-wing activism, and a large delegation was planning to attend a protest in Mexico City commemorating a 1968 massacre of students by government security forces. Taking over local buses was their usual transportation strategy.

The precise details of what happened next remain disputed, but the rough outline of the story is this: Five of the buses were separately set upon by federal and municipal police, who opened fire. Three students and three people in other vehicles were killed. Some of the students managed to escape and run into the city. Some were hunted by heavily armed men in masks; the body of one was found in the morning, stripped of his face.

And about 30 students from one bus and 10 from another were detained by municipal police, and never seen again.

The next day, parents of Ayotzinapa students began to arrive in Iguala, checking hospitals, jails and then morgues for their sons. Some found their boys; the families of 43 others didn't. Those students who had managed to escape told the families of the missing that the police had taken their sons. But the police said they didn't have them, and at the local military garrison, authorities also denied knowing where the young men were.

It took weeks for the parents to attract enough attention that the federal government was forced to open an investigation, and there is still no accepted explanation of what happened. The government has offered a series of them (the young men were mistaken for drug traffickers and killed by police; they were suspected of complicity with drug traffickers and handed over by corrupt police to a rival gang who shot them, burned their bodies out here in Cocula, about 20 kilometres away, and dumped the ashes in a river), none of which were accepted by an international inquiry. There is DNA evidence that one recovered body belonged to one of the 43, but it isn't clear his remains were recovered from the site that the government says they were.

The disappearance of the 43 rocked Mexico, and shocked the outside world. That so many students could vanish in an evening was disturbing, but the greater horror was what their disappearance revealed about how tightly entwined the narco-state is with the ostensibly elected one. Iguala's mayor, Jose Luis Abarca, and his wife, Maria de los Angeles Pineda, went on the run days after the killing, and were finally arrested in the capital; they are charged with organized crime, kidnapping and homicide. More than 101 people are now in custody in relation to the disappearances – municipal police and state ones, officials from every level of government; foot soldiers of two different drug cartels. No small number of the suspects are both.

The disappearance of the 43 became emblematic of the savage lawlessness of the Tierra Caliente – the hot land – where the bulk of Mexico's drug production goes on with the tacit, and sometimes overt, support of a weak state. And it brought into full public view an issue that had hovered like a dark miasma in Mexico, something everyone knew, few people discussed, and the government was able largely to ignore. The simple fact is that the disappearance of 43 students at the hands of police isn't even that shocking, by the standards of Guerrero and other states in this region. What made Ayotzinapa unusual was that the parents were able to come together to demand justice (although they still have no proof of what happened to their sons, and no one has been held responsible), and that they have managed to build a public movement in support of their case.

Searchers have been accused by federal authorities of destroying evidence of crimes and lowering the chances of successful prosecutions, although rare is the case that reaches prosecution.

Within a few days of the disappearances of the students, the parents organized into search parties, and they began to look for the bodies of their sons in the hills around the town. They found bodies – in ones and twos in shallow graves; and by the half-dozen, in known cartel dumping grounds. They found the remains of more than 200 people. But none of them were their own children.

And so other families began to come forward – people who were missing a child of their own, or a sibling or a parent, but who had been too afraid to look. They began to search, too, calling themselves the families of Los Otros Desparecidos, the Other Disappeared.

There are 400 families in the group now, searching for a total of 700 loved ones. The people they hunt for are among the 27,000 officially registered as missing in Mexico – although human-rights groups and security experts say that figure is a gross underestimation.

And few people take accurate measure of its cost, says Mario Vergara, one of the co-ordinators of the search. "When someone you love is killed, you feel terrible pain at the beginning – but over time, your pain diminishes until eventually you have the memories without the pain. Disappearance is the opposite. You have pain at the beginning, and as time goes by, and you have no answers, your pain only grows."

Father Oscar Prudenciano, the parish priest at San Gerardo, the church that has become the hub for the searchers, points out that this pain is felt far beyond the city limits of Iguala. "These things are happening everywhere in Mexico," he says, in a quiet conversation in his sacristy office. "The silver lining to the story of the 43, if you can say that, is that here we are looking."

Victor Velez searches each week - alongside his teenage daughter Guadalupe – for his son, who was 30 when he disappeared in 2014: ‘I’m glad every time that we find a body,’ he says, ‘because, if it’s not my son, at least I can help one of the companeros find theirs.’

MACHETES, STICKS AND SHOVELS

Victor Tepec Velez's son, Victor Juan Tepec, disappeared one morning in mid-2013, when he was 30. He was grabbed by armed men from a public-transit van he drove, in the early morning. Mr. Velez says there were witnesses, who told the family what they saw, but would not speak to the police. His son has a wife, and three children, the youngest just three months old when he disappeared. They were desperate to know where he had gone. People said he had been kidnapped, but there was no ransom demand. Mr. Velez thought maybe a drug gang had taken him to the mountains to work on a poppy plantation. He checked the morgue, the hospital and the jail. But he did not go to the police, and he did not go to the hills.

"I was afraid," he said. "Not for me, but for my other children."

Now he joins the group, somewhere between 15 and 20 people who gather to search each Sunday. Their mission is emblazoned on their black T-shirts, which read, on the front, "I will keep looking for you, until I find you" – and, on the back, "My child, until I bury you, I will keep looking for you." They use machetes and sticks and shovels to hack away the earth where a slight depression suggests the soil has been disturbed. They also carry a single iron spike, nearly a metre long, that they have repurposed: They drive it down into the dirt and then pull it up again, and inhale, searching for the telltale stench of putrefaction.

The searchers choose their sites based on anonymous tips that come in by phone or on Facebook. "Someone says, 'I saw something here,' or 'You should look there,'" explains Mr. Vergara. He digs each week in the hope of finding his brother Tomas, who was kidnapped in 2012 for a ransom the family could not pay.

A farmer who spots a shallow grave knows better than to disturb it, or to call the authorities – people who report crimes here swiftly end up dead. When a tip comes in to this group, they do not inform police, but rather turn up to search themselves – claiming (perhaps illusory) safety in their numbers. When they reach the site, they scatter to dig, while the Federal Police officers assigned to escort them, weighted down with bullet-proof vests and enormous guns, look on bemused, using their phones to take pictures of the diggers.

The searching has a random quality. They take a first path but not a second; dig beneath one tree but not the next; excavate one dip in the ground but not another. At one point Mr. Vergara digs and digs while an older man looks on. "I have to keep digging until he tells me to stop, because it's uncertainty that is killing him," Mr. Vergara says, and his pickaxe thuds into the soil until finally the man shakes his head slightly, and they fill in the hole and move on.

The searchers find bodies – almost every week, in fact. This is testament to just how many people have been killed and dumped in these hills as much as it is to the quality of the search. In its haphazardness, there is a suggestion that this weekly expedition is about more than just looking: This is ritual, and it is veiled protest. The searchers are saying, We have not forgotten. We are still looking for you. They are saying, to their doubting relatives, to the neighbours who mock them as fools, to the government that has entirely abandoned them: People cannot simply disappear.

We will not disappear.

The searchers choose their sites based on anonymous tips that come in by phone or on Facebook. ‘Someone says, “I saw something here,” or “You should look there,” explains Mario Vergara, who digs each week outside Iguala in the hope of finding his brother, Tomas.

A TRANSPORT ROUTE FOR DRUGS

The Sierra Madre rises in the distance above the foothills of Iguala – dark green mountains against a smoky blue sky. The mountain range is rich in gold, and it is ideal land for growing marijuana and opium poppies. An estimated 60 per cent of Mexico's poppies are grown in the state of Guerrero, on mountain plantations worked by young recruits and by forced labour, people like Mr. Velez's son, abducted on the streets.

The popularity of heroin and other opioid-based drugs is surging in the United States – the consumer market whose insatiable demand has driven so much of modern Mexican history. Opioids are displacing cocaine, which is produced down in South America but is also important for Iguala, which lies on a crucial transport route between Acapulco on the Pacific Coast and Mexico City.

The drug business is estimated to contribute anywhere from between 0.5 and 4 per cent of Mexico's $1.2-trillion (U.S.) annual GDP, and to employ at least half a million people in a country of 128 million. President Enrique Peña Nieto, who took office in December, 2012, is intent on wooing foreign investors, especially in a newly privatizing energy sector. After his election he contended the country was on a steady trajectory of improving public security, and during the initial part of his term the murder, kidnap and extortion rates did decline (homicide rates, for example, fell 28 per cent in the first two years). But Ayotzinapa, which garnered massive international attention, made a mockery of those claims.

In 2006, then-president Felipe Calderon had launched the bloody "drug war" that has so far claimed more than 100,000 lives. He deployed the military (perceived as relatively clean compared to police forces) and targeted "kingpins" – such as Joaquín (El Chapo) Guzman, the leader of the Sinaloa cartel, who was famously arrested, then allegedly escaped a supermax prison, before finally being recaptured in January with an assist from actor Sean Penn. That strategy has largely been maintained by Mr. Peña Nieto.

He has focused on dismantling the huge cartels that had carved the country into territories they ruled, operating almost unhindered by buying off officials at every level of government – all the way up, infamously, to the federal anti-drug czar.

Mexico's most notorious criminal organizations are diminished from what they were a few years ago. Los Zetas, in particular, whose savage violence made them a source of unparalleled dread, have had their territory and their scope reduced.

But in Iguala, and many other parts of Mexico, the perverse effect of the kingpin strategy has been a reduction of public security. Reining in the largest groups has created new spaces that are contested by smaller criminal organizations. "The guys with control of Iguala are renegotiating to see who will keep it, and we're in the middle – I'd rather live under the control of one gang than in an area being renegotiated," says Mario Vergara. "It's an all-out war for control of the [drug trade]."

And while organizations such as the Zetas and Sinaloa were, for the most part, strictly in the drug business, the new gangs have sought to diversify their portfolios – moving into everything from illegal logging to antiquities smuggling – and, in particular, kidnapping and extortion.

They also moved to protect themselves by embedding into local power structures: not simply buying off a police officer, a border official, or a cabinet minister, but actually making one of their own the mayor, or the police chief – as, it seems, the Guerreros Unidos, the United Warriors, did in Iguala.

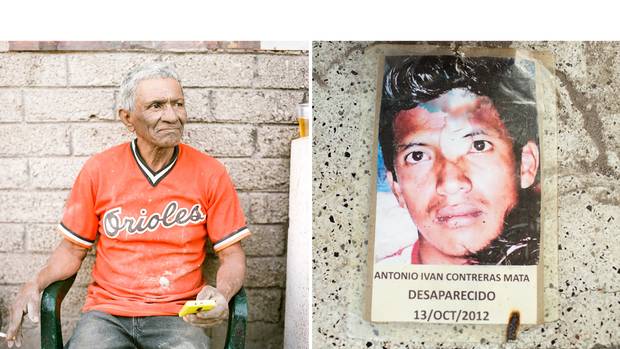

Guadalupe Contrera Oleg, of Iguala, says that his son, Antonio Ivan, then 28, went missing in October, 2012. Underlying many of the struggles families face is suspicion from the authorities and the community that the disappeared were themselves involved in criminal activity.

FRANTIC WEEKS OF WORRY

In the wake of the disappearance of the 43, the federal government disbanded the local police, and sent in a federal force to take over for the state one. Esteban Albarran Mendoza, from Mexico's traditional ruling Institutional Revolutionary Party, was elected mayor almost a year after the bloodshed that September night, and was at pains, in a recent conversation, to stress that he hopes to end his city's association with the disappeared.

"We're looking to earn the faith of the community by working with transparency," he said – in contrast with the last administration, "we don't cause problems, we solve problems."

The mayor works out of an office that looks like a supply closet, because much of the town hall is still a charred mess, after protesters attacked it, demanding action on the missing students. But Mayor Albarran emphasizes that security is much improved, and points to a beauty pageant under rehearsal in the main plaza. "People can go out, shop in the street, send their kids to school; farmers can harvest their crops, they can all do things peacefully and have trust."

His claims spark derision and open mockery among the families gathered at the Church of San Gerardo, a few kilometres away. "I don't know what city he lives in," says Mario Vergara. "At any hour of the day, you can hear gunshots in different parts of town. There are bodies in the streets every day or two." Yes, the former mayor's family was openly embedded in the Guerreros Unidos, while the new mayor has no open criminal ties. But people in Iguala will tell you Mr. Albarran stocked his cabinet with people who are known cartel associates (the mayor denies this). There is still nothing like a state that citizens can trust.

Camila, a core member of the families' network, describes it this way: When her 22-year-old daughter went missing in 2012, she didn't have to report the crime to police; local officers were there when her daughter was abducted, she says. (The Globe is identifying her by a pseudonym because she fears retribution for speaking with the media.) Her daughter had had a boyfriend whose father and uncles were in the state police, and deep in the drug business. She broke up with him, but they seem to have decided she knew too much to be allowed to leave, and police shot out the lock on the door of the family's cramped three-room house to take her. "Making a police report was the same as handing yourself over to the bad people," Camila says. And she had younger children at home.

After frantic weeks of worry, she nevertheless decided to try to report her daughter's disappearance. She made her way to the capital, hoping to go above authorities who might be directly implicated, and there she shuttled between agencies, trying to find someone who might help. She keeps a coiled notebook, a bright Angry Birds pattern on the cover, filled with looping handwriting that lists all the people she has asked for help: the office for violent crimes against women; the office for human trafficking; the specialized unit in the trafficking of minors, humans and organs.

She came no closer to finding her daughter. So in the days after the Ayotzinapa students disappeared, she cautiously made her way to the church – well, she had been going there anyway, she says, "holding mass after mass for my daughter's return." Now she has joined the search.

And she gave her DNA, for the national registry of missing persons. But when she asked the official who took her blood sample about making a police report, he advised against it, she says. Indeed, the dozen Otros Desparecidos families interviewed by The Globe said that state officials actively discouraged them from making a police report. "Look what they did to the 43. What could they do to your family?" is how Camila recalls the warning.

For Mr. Vergara, the logic behind this advice – a government telling its citizens not to report a crime because the state can't protect them from its own police – is clear. "The officials go to international meetings and they are asked about enforced disappearances and they can show the number and it's very low and they say, 'Nothing is happening in Mexico!'"

That may sound like conspiracy theory born of despair, but Alejandro Hope, one of Mexico's foremost experts on public security, concurs that it is policy to discourage people from reporting crimes. "There are eight million extortions per year, according to the national statistics board, and 6,000 are reported; there are 30,000 kidnappings and 1,500 are reported," he says. Disappearance figures are, if anything, even more distorted.

"What makes this grotesque is that governors and public-security officials will brag about declining numbers," Mr. Hope adds. "Ideally you'd want the number of reports increasing" – demonstrating growing trust in authorities – "but try to convince them of that."

The federal government's national-security commission, foreign-affairs ministry, attorney general's office and interior ministry, which handles public security, all declined repeated requests for comment.

Half the people who gathered at San Gerardo to search on a recent Sunday said they routinely pass people in the street they know were involved in their family member's disappearance. Mr. Vergara lowers his voice to describe the price one member of the group, a silent woman who is cleaning off tools in the church yard after the dig, paid for reporting. She is slight, with long dark hair, and wears large-framed purple glasses. Just two weeks ago, Mr. Vergara says, she made a formal police report about her son, missing for a year. The next day, her surviving son was shot dead in the doorway of their home. She has returned, silently, to digging.

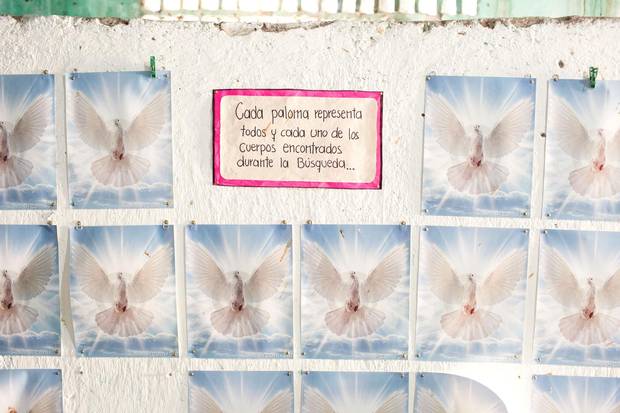

A wall of doves lines church walls in Iguala at the searchers’ headquarters. The family members of missing people put a dove up for every body they find in a clandestine grave.

EVEN THE POLICE ARE FRIGHTENED

Carlos Zazueta, a researcher in the Mexico City office of Amnesty International who has made extensive study of the disappearances, says that reporting the crime would be unlikely to help, even if doing so weren't discouraged – or punished – by authorities.

The police protocols for responding are Byzantine, he says. Authorities often tell panicked families that they must wait 72 hours to make a missing-person report, although this is nowhere in the law – and then they address the case by sending letters (yes, letters) to other jurisdictions with details of the missing person. "They don't collect evidence, they don't look at GPS on cellphones – they ask for phone records months or years later, and the companies are not obliged to keep them that long," he says.

Sometimes the police are not incompetent as much as frightened – they know or suspect who has abducted the person and that there will only be negative repercussions from getting involved, he explains in an interview at Amnesty International's bustling Mexico City office, ringed by high walls and security guards. "Or you have good investigators who are overwhelmed by cases: In some places it's one lonely guy or woman trying to find 200 people with no team." Sometimes police are criminally involved themselves.

A law now before Congress, drafted with input from the Ayotzinapa families and those of other disappeared, may help. It would allow families to report a missing person to another jurisdiction, if they suspect that local authorities are directly involved in the crime. It lays out a streamlined national protocol for responding, including the use of rapid-response teams and involving family members, who are often the best source of information. "The new law is far from perfect, but it's better," he says. "Maybe you will end up with a good law that won't be applied – that's the problem of this country."

Underlying many of the struggles families face is suspicion from the authorities and the community that the disappeared were themselves involved in criminal activity. In Iguala, for example, in a café near the church, the staff openly mock the families setting out on the search. "Those people are fooling themselves," says a server who is willing to be identified only by her first name, Isabel.

The students at Ayotzinapa were known for acting up, she says, adding that probably many of Los Otros Desparecidos had similarly poor judgment. "What the parents don't realize is that a lot of the time their children are involved in things they don't know: They're on the wrong track," she adds, as her colleagues nod firmly.

Mr. Zazueta says this attitude is typical. "If you have a disappeared woman, the police will say, 'Oh, she is with one of her boyfriends because her mother did not raise her properly' – that is very common – or, 'It's not crime, it's family problems.'"

But in the great majority of cases Amnesty has examined, he says, the disappeared person had no connection with illegal activity, "and when police say they have, they can produce no evidence."

Others, such as Camila's daughter, may have had peripheral knowledge of criminal activity, knowledge they perhaps never wanted. Even if the person had direct involvement in criminal activity, this is no justification for execution or enforced disappearance, Mr. Zazueta notes. There are equal numbers of men, women and children among the registered missing; a third are under 18, most of those teenagers. Some are taken for ransom, and some are taken for forced labour, and some are taken simply to show power, to instill fear.

One thing the families hope the new law will do is simplify the procedure for having someone declared disappeared: As Mr. Vergara describes it, disappearance devastates lives twice over. Many families lose a revenue earner – his missing brother had a wife and two young children – and they spend precious resources on the search, perhaps leaving their own jobs to do it.

The missing person's bank account is frozen, and so is title to any home or property they own. And yet, that doesn't stop creditors from calling. Without a body, the family cannot get a death certificate. A mother fearing for her own life can't flee, because she can't get a passport for children without the disappeared father's signature.

It takes five years to have a person declared dead, and the declaration comes at its own cost. "That is very difficult for the person to accept – they don't want to accept it and also it may close the investigation," Mr. Zazueta explains. Instead, families want the government to create a special certificate that says that someone is disappeared. And while the current law says that families are entitled to financial compensation when a family member dies through organized crime, there must be a conviction in the case for them to receive the funds.

But given that the murders are so rarely investigated, families almost never receive the compensation: The Mexican government has paid it fewer than a dozen times.

Even when bodies are recovered, Father Prudenciano says, he holds a funeral mass, and that's it. "There's no following up, no further investigation of who took them, who killed them, just 'I got my family back.' Because they're afraid to lose another one."

Mr. Hope, the public-security expert, calls the Peña Nieto administration's progress on these issues abysmal: The low-hanging fruit in improving security has been picked, he says, while promised steps toward transparency in policing and criminal-justice reform have not been taken. What is the likelihood, he asks, that a poor family in Iguala can obtain a conviction in the case of a disappeared loved one, when the government has yet to resolve even the case of the 43?

"Ayotzinapa is illustrative: You have 113 indictments, and zero convictions," he says. Most of those charged are in jail; no trials have yet been held. "There's a lot of corruption, and also just a lot of incompetence. This case is iconic, the eyes of the world are on Mexico, the president's reputation is on trial. This is really depressing – the one case where you really had to get it right and you couldn't do it.

"There will not be closure on Ayotzinapa," he predicts.

‘I will not rest until I find him,’ says Bertha Moreno Garcia, of her son, Jose Manuel Cruz Moreno, who was 22 when he went missing in 2009 from a small community on the outskirts of Iguala, after telling his mother that he was setting out to buy new shoes and then attend a party. ‘It is like a cancer that is finishing me from the inside.’

'NOW I HAVE THE COURAGE'

When the Sunday searchers hit bone – white bone, or sometimes the metallic shiny grey of burnt human remains – they stop digging. They mark the place with stones, the way peasant farmers indicate directions in their fields, and they summon the federal government to do an exhumation and collect evidence.

Federal authorities are apparently underwhelmed about the do-it-yourself searching. While the forensic investigators would not answer questions from The Globe, Mr. Vergara and Father Prudenciano say searchers have been accused by federal authorities of destroying evidence of crimes and lowering the chances of successful prosecutions (although virtually none of these cases have been pursued for prosecution).

Mr. Vergara concurred they have no formal knowledge of forensic archeology. "He's a construction worker," he says, nodding toward a grizzled man in a Stetson. "He's a waiter. I'm a beer distributor. We don't have any expertise. All we have is our pain."

Family members search the mountains near Huitzuco.

Mr. Zazueta, the Amnesty International researcher, says the government has left them no option. "The problem for government is, if they start looking for people, they find other people: 'Oh, maybe these are the right bodies?' 'No.' 'Oh, these?' 'No.' 'So who are they?'"

Already, there are more than 10,000 unidentified bodies on the federal register.

And there are many, many more families with this raw wound at their core. "It's a terrible situation when you feel government is ignoring you so much, you go yourself to find the corpse of your loved one somewhere in the country," says Mr. Zazueta.

"This is not only personal; it has a social impact as well. Government has to provide the means to recognize the wrongs that were done."

At San Gerardo, the doors stay open all day; scolding swallows nest in the rafters. Sunday-school classes, the choir and the ladies' auxiliary meet in groups under giant mango trees in the yard. Father Prudenciano, jowly with a squiff of grey hair, keeps one eye on the comings and goings, mindful that even priests are not safe, trying to gauge how far the protection of the international attention on Ayotzinapa extends to the families here.

In the courtyard sit those who are looking. And inside the church hall, there are two walls decorated with cut-outs of pale blue doves. One wall has a dove for each body the searchers have found. There are 130, papering it floor to ceiling. The second wall has just three doves: the bodies that have been identified and returned to their families. The other 127, Mr. Vergara says – those are families who are still afraid to look.

When Victor Tepec Velez goes to look for his son each week, he brings his youngest daughter with him. Guadalupe, now 14, was always closest to her big brother. He called her Lupita.

"They kill you, by not letting you find your family," she says matter-of-factly. "The uncertainty. My mom always wanted to look for his grave. She always wanted to but didn't know how – now I have the courage to do it." But she rarely strays far from her father's side.

Mr. Velez digs stoically, trudging through the brush with his head down. He snaps it up when he hears someone say they may have found something.

"Every time, I'm asking God that it will be my son," he says. "In the moment – I'm resigned. When I see it's not my son, that gives me the strength to keep looking. And I'm glad every time that we find a body because, if it's not my son, at least I can help one of the compañeros find theirs."

The searchers eat a simple meal together at the church in the late afternoon, and a day they find no one, when there is no blue dove to add to the wall, their emotions are raw.

"When we find someone, it's a joy, and it's a sorrow," Mr. Vergara says. "Because it's a person. How ugly this is. How horrible. How wonderful. How horrible. We found you."

Stephanie Nolen is The Globe and Mail's Latin America correspondent.

LATIN AMERICA: MORE FROM THE GLOBE'S STEPHANIE NOLEN

In Brazil, race is a confusing, loaded topic

3:03