Not long after disappearing from Winnipeg, the young man writes home with a mixture of regret and practicality. This is going to hurt the family, his letter states, but it is the path in which God has guided him. He apologizes to his mother for leaving the country without her blessing. And he asks his family to pay his student loans, one provincial and one federal.

The next letter is different, a nine-page missive that is alternately hectoring and affectionate. In it, the former University of Manitoba student urges his family to leave Canada, a "filthy place" where the media tells nothing but lies about "Talibans, al-Qaeda and other groups fighting for the sake of Allah." He proceeds to give instructions to each relative: start wearing hijabs, stop watching Hollywood movies, begin praying, keep your children out of public school.

The correspondence, revealed in a recent U.S. court filing, yields a telling portrait of the mindset of an alleged Canadian jihadist at a time when the federal government is increasingly investing in ways to avert the spread of extremist ideology. The letters were written by Maiwand Yar, one of three students in Winnipeg who mysteriously vanished from Canada a decade ago before surfacing in the remote tribal areas of Pakistan. Authorities allege the trio became highly dangerous terrorists by joining remnants of al-Qaeda's core leaders overseas.

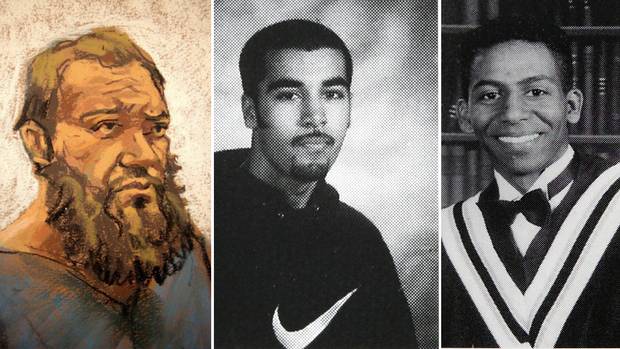

Left to right: courtroom sketch of Muhanad al-Farekh, class photos of Maiwand Yar and Ferid Imam.

Jane Rosenberg/Associated Press; John Woods

The fate of the cluster, which left Canada in 2007, remains partly unknown. The two Canadian-citizen suspects, Mr. Yar and Ferid Imam, have never resurfaced, although Mr. Yar's family received a call from Pakistan saying he had been killed. The third student, Muhanad al-Farekh, an American citizen, was captured in Pakistan and is scheduled to stand trial on Tuesday in New York on a slew of terrorism charges in a proceeding that may resolve lingering questions about the group.

An international manhunt for the three students was first reported in 2010 by The Globe and Mail, when such disappearances and zealotry among young extremists were not the pressing policy challenge they are today.

Since then, the advent of the Islamic State – an al-Qaeda offshoot that captured swaths of Syria and Iraq – has drawn legions of radical hardliners from around the world to join its professed project of building a new caliphate. Dozens of Canadians went – or tried – to join the militant group, prompting sprawling investigations and hard questions about what the government should do with such individuals. Now the Liberal government has launched a multimillion-dollar federal counter-radicalization centre and plans to hire a special adviser to help develop a national strategy.

That adviser might start by reading the long handwritten letter that Mr. Yar, then in his early 20s, sent home to Canada. In it, he articulates his logic of jihadism, giving an unusually clear-eyed view into the thinking of Canadians who fall under the sway of such ideology. (While previous court filings have described aspects of the letter, the full text has never been made public until now).

Mr. Yar starts out by avowing that he is not crazy or misguided, but rather it is his own family and the Canadian Muslim community who have gone astray. "It hurts me so much that you believe I left because I was brainwashed and didn't know what I was doing," Mr. Yar writes his family, then proceeds to cite the specific scriptures and scholars who inspired him.

Casting himself as part of a small minority of true believers, he complains of a wide-ranging conspiracy by the West, its Middle Eastern allies and deceptive preachers to hide the true nature of Islam. As for "al-Qaeda and [the] Taliban, their only purpose is to apply the rulings of Allah … but people call them terrorists," Mr. Yar laments. He goes on to say he has met members of such groups firsthand and found them to be "the best people in the world."

Maiwand Yar letter to family by The Globe and Mail on Scribd

The self-radicalizing Winnipeg cluster that included Mr. Yar was once viewed as an urgent national-security problem by counterterrorism officials in North America. A former top U.S. intelligence official told The Globe in 2010 that he had urged then-president George W. Bush years earlier to take drastic actions against these suspects and similar ones in Pakistan. That conversation immediately preceded a period in which the U.S. Central Intelligence Agency vastly increased its use of overseas drone strikes.

For years, the fate of Mr. Yar and Mr. Imam, his fellow Canadian suspect, has remained unclear. Court records filed last week in New York note that Mr. Yar and Mr. Imam "have never returned to Canada." They also indicate that later in 2009, the same year in which the longer letter was written, Mr. Yar's family received a call from an unnamed individual in Pakistan informing them that he had been killed, although it is not clear by whom.

One member of the circle has surfaced, however: Mr. Farekh, who was born in Texas and raised in Dubai before going to the University of Manitoba. According to the New York Times, Mr. Farekh was the subject of a heated debate at the highest levels of the U.S. government over whether he should be killed or captured. The paper reported that former U.S. attorney-general Eric Holder argued that the suspect's American citizenship tilted the scales away from a presidentially decreed drone strike and in favour of capture, extradition and a criminal trial.

Now, Mr. Farekh will appear before a Brooklyn jury on Tuesday. He was captured in 2014 by Pakistani authorities and handed over to American law-enforcement officials in 2015. Among other charges, he stands accused of assembling a massive car bomb that failed to detonate during an attack on a U.S. military base in Afghanistan. Mr. Farekh has pleaded not guilty to the charges. His lawyers did not respond to a request for comment.

Last week, the correspondence was entered into the public record by U.S. prosecutors, who intend to use the writings as evidence of Mr. Farekh's mindset at the time of his disappearance in 2007. Prosecutors say the three men were co-conspirators and therefore shared motives and goals. The correspondence includes two letters from Mr. Yar and a brief e-mail from Mr. Imam.

Born to an Afghan family who came to Canada as refugees, Mr. Yar was arrested for selling crack at the age of 20. Not long after, he began to gravitate toward radical jihadist ideology, according to court documents, which allege that the three students became radicalized in part by watching online sermons by Anwar al-Awlaki, a militant cleric and American member of al-Qaeda. The young men made a pilgrimage to Saudi Arabia together in December, 2006. A few months later, they were gone.

Soon after he left, Mr. Yar's family received a short letter telling them he was doing God's will and asking them to pay his student debts. Nearly two years later, they received a long handwritten missive. Addressed to a family home in Calgary on a blue airmail envelope, it carried a return address of a post office in Peshawar, a city in northwestern Pakistan.

In the letter, Mr. Yar advises his family members in detailed terms how to rectify their behaviour and urges them to consider moving to Pakistan. He swears that he will never return to Canada. "This is the right path I have chosen," he concludes. "And this is the place where I hope to get my shahada [martyrdom]."

Mr. Yar offers no specifics about what he is doing, but in a postscript, he belatedly asks his relatives not to tell the government about the correspondence. His family ignored the advice: in 2015, Mr. Yar's brother told The Globe that the family had handed the letter over to the police.

Despite Mr. Yar's jihadist leanings and his authoritative tone, the letter displays a certain naivete. "It's as though he has no concept yet of what it actually means to be there and what intelligence agencies are involved," says Daniel Koehler, director of the German Institute on Radicalization and De-radicalization Studies. He added that the Canadian man does not appear to grasp that he could be "close to being killed by a drone strike."

Analysis: Five takeaways from Maiwand Yar's letter

Amarnath Amarasingam is a Senior Research Fellow at the London-based Institute for Strategic Dialogue, and co-directs a study of Western foreign fighters at the University of Waterloo.

Over the past four years, I have co-directed a study based at the University of Waterloo of Western foreign fighters, and have interviewed dozens of fighters from a variety of Western countries. Throughout my research, I have read a few "letters home" from men and women involved in jihadist factions fighting in today's conflict in Syria and Iraq.

Yet the 2009 letter written by Maiwand Yar to his family, obtained by The Globe and Mail, still provides a rare window into the detailed motivations and personal justifications of a young Canadian man joining what was then an al-Qaeda-led jihad in Pakistan – in his own words.

Here are some important takeaways from the letter:

First, it is important to note and understand the importance of religiosity in the lives of these youth. His letter is infused with not only scriptural literalism, but also a deep concern that he must communicate the "truth" to his family before the day of judgment and before it is too late to save them. (The notion of religiosity should be differentiated here from religious orthodoxy. We have to take the religious worldview of jihadists seriously in order to understand their choices, regardless of how reprehensible it may be to the majority of Muslims.)

In jihadist discourse, there is a concept roughly translated as "loyalty and disavowal" – the belief that in order to be a true Muslim, one must live a life that is pleasing to God and oppose that which is displeasing to Him. In the jihadist world, democratic institutions and Western culture must be avoided. It is not surprising, then, that Mr. Yar spends almost half of his letter home pleading with his family to stay away from fashion, Hollywood, and public schools, all of which he believes are deeply harmful for Muslim identity. Toward the end of the letter, he inevitably asks his family to leave the West altogether and move to Pakistan.

The second important element of the letter, one which is a fairly common theme when such individuals call or write home to their families, is Mr. Yar's genuine attempt to communicate why he made the choice. A lot of family members of jihadis whom I have interviewed over the years believe that their children were brainwashed by religious leaders or close friends. They insist that they could get their children to "snap out of it" if given some time to talk with them.

Indeed, the very first paragraph of Mr. Yar's letter home states that, "it hurts me so much that you believe that I left because I was brainwashed and didn't know what I was doing." He wants his family to understand and spends the next several paragraphs explaining that his decision was his alone, wasn't made on a whim and is a choice he believes is demanded by God himself. The remaining key takeaways are all, fundamentally, his attempt to unpack his reasons for joining the fight and what he believes his family does not understand.

Thirdly, then, Mr. Yar makes the argument that jihad is an individual obligation upon every able-bodied Muslim. For this, he draws from well-established jihadist literature and writers who have argued that when parts of the Muslim world are under attack from the "non-believers," it is the job of every Muslim to join the fight. And that, for young men like him, no permission of parents is required.

Fourthly, Mr. Yar almost attempts to predict the counterarguments that his family may employ against him; namely, that the vast majority of Muslims disagree with his choice to join an organization like al-Qaeda and, therefore, he must have been led astray. He quotes a hadith (reports of sayings and actions of the Prophet Mohammed) arguing that it is never the majority that sees the truth and fights to preserve it. Rather, truth is always held by the minority while others languish in ignorance and remain oblivious.

This is a popular hadith among jihadists and has appeared repeatedly in propaganda released by both al-Qaeda and the Islamic State. They argue that those who sacrifice their lives for the cause of truth are always in the minority. Indeed, they are the small vanguard, sacrificing wealth, education and creature comforts for the greater good. They will try and persuade the masses of the truth, but even if they fail, they will be rewarded in the afterlife. They are not ignorant, uneducated and brainwashed youth, they argue, but rather noble fighters on the path of God.

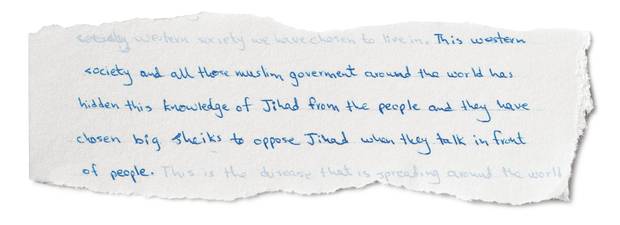

Fifthly, the harshest criticism of jihadists is often saved for voices of moderation within the Muslim community. Mr. Yar, on the very first page of his letter, argues that "the Western society and all those Muslim government around the world has [sic] hidden this knowledge of jihad from the people and they have chosen big sheikhs to oppose jihad when they talk in front of people." I have heard this argument repeatedly during my research. Several Canadians who migrated to fight with IS in Syria repeatedly pointed out that religious scholars and imams in Canada were completely ignorant of the importance of jihad, were too scared of law enforcement to be honest with youth about it, and were sellouts that were not to be trusted or listened to.

Mr. Yar's decision to leave Winnipeg for Waziristan was made a decade ago. Today, few Canadians know his story. Authorities won't speak to what fate may have had in store for him abroad. His 2009 letter from Pakistan closes with the expressed hope that he would attain "martyrdom" there.

These days, most Canadians are much more aware of the phenomenon of foreign fighters – young people from the West who join fights in foreign lands, often on behalf of proscribed terrorist organizations. Previous conflicts in Somalia, Chechnya, Bosnia and Afghanistan have all attracted foreign recruits. But the Syrian conflict of the past six years has been different, both in terms of sheer numbers as well as the diversity of countries from which foreign fighters have originated.

It has been a fundamental game-changer. Unlike in previous conflicts, the foreign fighters who migrated to Syria were largely young men adept at using social media while they lived in the West. They were the digital generation. At home in the West, they posted images on Facebook and tweeted about their lives. Once in Syria, they continued to do the same, only this time they posted photos of the battlefield, live-tweeted about their migration experience and reached back into their home countries to recruit their friends and families.

Their online presence also made it easier for researchers like myself to reach out to them and ask for interviews. The conflict and technology and scale has changed but one thing hasn't – their justifications for joining a jihad. And they inevitably echo the rationale set down years earlier, on pen and paper, in this detailed letter from Maiwand Yar.