TABLE OF CONTENTS

Part 1: Adrian Morrow on what they are

- What's going on in Iowa

- Why does Iowa get to go first?

- What are the arguments in favour of this system?

- Why don’t some people like the system?

- Any chance this system will change?

Part 2: Paul Koring on what is and isn't at stake

- Iowa isn’t America, not even close

- For all the fuss over Iowa caucuses, not many bother to vote

- Democrats and Republicans do it differently

- Iowa isn’t very good at picking winners

What's going on in Iowa

By Adrian Morrow in Des Moines, Iowa

It sounds like a democratic ritual from a bygone era.

Instead of going to polling stations and casting ballots, voters gather on a midwinter evening – in church basements, school gymnasiums or living rooms – to debate and choose the person they want as their party's presidential nominee.

These are the Iowa caucuses, the first electoral test of the U.S. presidential race.

To supporters, they are the epitome of participatory democracy. You have a good discussion about politics with your fellow party members and think long and hard before making your choice.

To detractors, they are an anachronism. The time commitment leads to low voter turnout, while the odd glitch calls into question their democratic worth.

One way or the other, the caucuses can make or break a presidential campaign. Post an unexpectedly good showing, and an upstart candidate can build enough momentum to pull ahead of the field; post a poor one and emerge wounded.

Sanders, Clinton in tight Iowa race

2:35

Why does Iowa get to go first?

According to the state's historical society, the caucuses go back as far as the mid-19th century, around the time Iowa joined the Union. But they only really gained importance in the 1970s.

Following the divisive 1968 Democratic convention, where Hubert Humphrey took the nomination despite having relatively little grassroots support, the party reformed its nominating process. The caucuses, which had previously consisted mostly of party insiders and activists, were now open to all registered Democrats. The Republicans adopted the same system in Iowa ahead of the 1976 election.

That year, on the Democratic side, a little-known former Georgia governor named Jimmy Carter realized he could use the new system to his advantage. He focused his attention on early-voting states, including a big push in Iowa. Mr. Carter placed second here (after "uncommitted" voters) and got the momentum he needed to overtake higher-profile candidates and ultimately reach the White House.

Former U.S. president Jimmy Carter at the Historic Plains Inn & Antique store in Plains, Ga., in 2003.

WALTER PETRUSKA/ASSOCIATED PRESS

David Yepsen, former chief political reporter at the Des Moines Register, watched the attention on the caucuses build in the years that followed. "I went to a Carter press conference once and I was the only reporter who showed up," he says. "I've seen these go from a handful of enthusiasts meeting with candidates in living rooms to huge events."

Mr. Yepsen recalls one time, during the run-up to the 1988 caucuses, borrowing a hotel clerk's car in a town of 1,000 people to go for a late-night pizza run with then-senator Joe Biden.

"The clerk handed him the keys and said, 'Here, take my car, but you have to be back by midnight because I have a date tonight,'" he says. "That's something you don't see any more."

Now, candidates often start campaigning here more than two years before the vote, staging hundreds of events across the state, flying in armies of staffers and saturating local television and radio with ads. The national and international media descend on Iowa too – the Des Moines Register estimated this year's media pack will include 1,600 reporters and camera crews – turning the state into a temporary extension of Washington.

What are the arguments in favour of this system?

Not surprisingly, political geeks in Iowa love it. There is some self-interest involved (it's nice for both the ego and the economy to get so much attention), but they also contend the system is good for the campaign overall by putting the candidates under a microscope.

The long campaign and the state's modest size, people here argue, force candidates to do more small-scale events and retail politicking. This can allow underdog contenders to get their message out even if they can't afford to match better-funded rivals' ad buys.

"The fact it is very retail and very grassroots is excellent," says Art Behn, chair of the Democratic Party in Dallas County west of Des Moines. "It allows all candidates to put their ideas forward and get heard."

Timothy Hagle, a political scientist at the University of Iowa, says the deliberations that happen in the caucus room allow more voter engagement than a typical election.

"That's how democracy works. You're getting people of the same party together and saying, 'Who do we want to represent our party?' Getting together and talking about that rather than just having people throw advertising at you," he says.

It's a responsibility many voters take seriously. Jannelle Noller, a 74-year-old retiree who moved to Iowa from Seattle for her husband's job, has been attending as many Republican events as she can to get an up-close look at the candidates. She figures she'll make her decision at the caucus itself.

"I'm going in with an open mind, and I'll see what people say," she says on the sidelines of a Donald Trump rally in Pella. "It's good to hear how other people feel, what they see in a candidate."

Why don't some people like the system?

The caucus process – sitting in a room for two hours on a week night debating politics with your neighbours, rather than voting in private at a polling station – doesn't appeal to most people. Turnout is typically just 20 per cent. Some observers argue this skews the process in favour of niche candidates who are good at mobilizing hard-core party activists, and disadvantages more moderate contenders who appeal to a broader electorate.

"Those who [attend caucuses] are going to tend to be older than the electorate as a whole and more committed to a particular candidate than many other voters might be," wrote Doug Mataconis on the Outside the Beltway blog after the 2012 caucus. "This is why candidates like Rick Santorum, Ron Paul and before them Pat Robertson tend to do well in caucus scenarios and poorly in primaries."

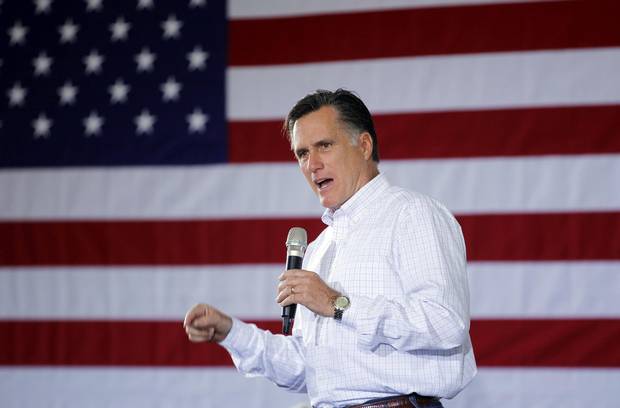

Mitt Romney speaks at a campaign rally in Dubuque, Iowa, on Jan. 2, 2012.

BRIAN SNYDER/REUTERS

And then there are the screw-ups. In the 2012 Republican caucuses, Mitt Romney was declared the winner on caucus night. But two weeks later, a recount confirmed Rick Santorum had actually taken it. Oh, and votes from eight precincts were lost in the mail. This all ended being academic anyway: By the time of the Republican National Convention in August, 22 of Iowa's 27 delegates were actually supporting Ron Paul, who finished third. That's because his organizers had done a better job getting their people elected at the subsequent county, district and state conventions.

(The GOP has since instituted changes to make the reporting of results faster and easier, and to oblige delegates to respect the vote at the caucuses.)

The arguments against the caucuses are a microcosm of the larger debate over whether the current system for choosing presidential nominees is a good idea. As it is now, the process goes state-by-state, stretches over months and gives disproportionate influence to a handful of smaller states at the start.

Any chance this system will change?

Both parties have rules in place protecting Iowa's first-in-the-nation status. And they have punished other states that have moved their primaries up in an effort to increase their influence. When Florida moved its Republican primary to Jan. 31 in 2012 (which forced Iowa to holds the caucuses Jan. 3 to stay well in first), party brass took away half the Sunshine State's delegates.

People have suggested alternatives, including a national primary in which every state votes the same day, or having states representing different regions of the country with different demographic makeups vote on the same day.

But Mr. Yepsen doubts things will change any time soon. Candidates who win the nomination have no incentive to change the system, as it clearly worked for them. Unsuccessful candidates, meanwhile, have built up organizations in the state that they may want to use for future runs.

What's more, party leaders would have to agree on a new system. The current process came into being largely inadvertently, and it's difficult to imagine everyone reaching a consensus on how to create a new one.

"The country can't agree on an alternative nominating process, like a regional primary or a national primary," Mr. Yepsen says. "It's just political inertia."

Four reasons why Iowa isn't that big a deal

by Paul Koring in Washington

1. Iowa isn't America, not even close

Hillary Clinton supporters look on during an event at BR Miller Middle School in Marshalltown, Iowa, on Jan. 26, 2016.

JUSTIN SULLIVAN/GETTY IMAGES

First to vote, the Hawkeye State gets disproportionate attention, especially since Iowa is so drastically unrepresentative of the United States.

Iowa is home to roughly 3.1 million people, less than 1 per cent of the total U.S. population of 320-plus million. New Hampshire (pop. 1.3 million), the second state on the party-nomination selection calendar, is also unrepresentative of the nation, but Iowa is less diverse.

In fact, Iowa is far more white than the rest of the nation: In 2014, the white population of Iowa totalled 92 per cent, compared to 77 per cent nationally; about 3.4 per cent were African-American (compared to 13.2 per cent nationally), and 5.6 per cent were Hispanic (17 per cent nationally). Percentages exceed 100 because many Hispanics opt to also identify by race as allowed by the decennial census.

Iowa is not just more white – it's population is also more rural than the rest of America. Nationally, 81 per cent of the U.S. population lives in urban areas; in Iowa, it's just 62 per cent. And the Iowans who do live in cities live in small ones: The state's biggest city, Des Moines, is ranked 104th by population nationally with 206,000.

2. For all the fuss over Iowa caucuses, not many bother to vote

U.S. Democratic presidential candidate Bernie Sanders speaks during a campaign rally at the Des Moines Area Community College in Ankeny, Iowa, on Jan. 10.

SCOTT MORGAN/REUTERS

Only registered members of the Democratic and Republican parties can vote in Iowa Caucuses. Currently, there are about 584,000 card-carrying Democrats and 612,000 registered Republicans.

But even in high-turnout years – those when no incumbent president is running for re-election – only about one in five registered party members actually bothers to spend an evening listening, arguing and being counted in caucus. That's an estimate because the Democratic Party refuses to release an actual raw votes figure. But a 20-per-cent turnout is considered good.

Republicans do release vote numbers. In 2008's hotly contested Republican race with multiple candidates – similar to this year – only 120,000 party members appeared at caucuses, a 20-per-cent turnout.

That means that only 250,0000 voters from both parties – in a tiny, entirely unrepresentative, overwhelming white, largely rural, mid-western state – decide the outcome of the "first in the nation" vote.

3. Democrats and Republicans do it differently

Pro-Trump flyers at a campaign rally at the University of Iowa on Jan. 26.

SCOTT MORGAN/REUTERS

In a caucus state like Iowa, voters don't just go to a polling station and cast a vote, as they do in primary states such as New Hampshire. Instead, they go to a meeting place for a gathering (caucus) where they listen to an actual candidate or, more often, to a candidate's advocate. They discuss, ask questions, perhaps even argue and then vote.

Iowa caucuses start at 7 p.m. local. They usually last about two hours. Exit polls are notoriously unreliable, not least because everyone is supposed to stay until the end and, by definition, if you're inside, you aren't talking to exit pollsters outside. Results are counted and made public, often by 11 p.m., although sometimes the delegate assignments and final totals aren't available until the following day. Each party reports separately. Delegate assignment also varies by party.

There are 1,681 voting precincts in Iowa's 99 counties, but often several precincts gather at the same location (school, community hall, church basement) to conduct their caucuses. The two parties organize and run their caucuses at different locations.

Results are reported to and tabulated by the respective Iowa party headquarters, not the state elections office.

In Democratic caucuses (roughly 1,100 locations are expected), any candidate with less than 15-per-cent support gets cut after an initial round of voting. So organizers count everyone in the room, then count how many supporters have gathered in each candidate's corner, and then disqualify those candidates falling below the threshold. Backers of a candidate who fails to meet the vote minimum can then throw their support behind one of the other candidates, or choose to not support anyone.

In Iowa this year, the 15-per-cent threshold could turn out to be bad news for former Maryland Governor Martin O'Malley, who may redefine "distant third" in a three-way Democrat race.

In Republican caucuses, there is no required minimum level of support, and the ballot is secret. About 900 locations are expected.

In order to vote in either party's caucus, registered voters have to show up. There are no advance ballots and no absentee ballots, with one exception: This year, for the first time, Iowa military members can participate online.

.

4. Iowa isn't very good at picking winners

Al Gore walks out of a barn with members of the Roarson and Wilts families as he tours their farm in Sloan City, Iowa, on Jan. 13, 2000.

DOUG MILLS/ASSOCIATED PRESS

Only once since the Iowa caucuses became the first important date on the election calendar for both parties, and when an incumbent president wasn't running for re-election, have Iowa voters correctly selected presidential nominees for both parties.

That was in 2000, when then vice-president Al Gore came first in the Democratic caucuses and George W. Bush was picked in Republican caucuses. Both went on to win their parties' nominations, and Mr. Bush beat Mr. Gore by a wafer-thin margin, but only after the disputed Florida vote was decided by the Supreme Court.

Here's a list of Iowa winners. The names of eventual party nominees are in bold, and in all caps if they were elected president.