Officers patrol in the Babilonia favela community, which stands on a hillside above Copacabana beach, an Olympic venue site, in Rio de Janeiro on July 26, 2016.

MARIO TAMA/GETTY IMAGES

A series of dramatic crimes in Rio in the past few months have created the sense – both here in the city and abroad – that security is deteriorating. In April, warring gangs used grenades in a battle next to a mall in Leblon, the city's chicest neighbourhood. In late May, a teenage girl was gang-raped by as many as 30 men who shared video and pictures of the attack on social media. That same month, police and carjackers engaged in a shootout in the middle of a historic avenue full of shoppers and strollers on a Saturday afternoon.

Five police officers were shot in different areas of the city in a single 12-hour period on June 14; two of them died. A man robbing a woman in July stabbed her in the neck, and she bled to death in front of her seven-year-old daughter. Amnesty International launched an app for favela residents to report gunfire in their neighbourhood, and it was overwhelmed with shootings logged on its first day.

Back in 2009, when Rio bid to host the 2016 Olympic Games, "security" was the most-used word in the pitch: The city said it was already making strides to bring down its historically astronomical level of violent crime, and would have the situation well under control by the time the the Games came to Rio. But now, with just days to go before the Games, the headlines make that pledge look hollow.

Soldiers patrol past a poster promoting the Olympics on Rio de Janerio’s iconic Copacabana Beach on July 30, 2016.

WILLIAM WEST/AFP/GETTY IMAGES

Headlines aren't always borne out by data, of course, but this time they are: The newest statistics from the state security agency confirm the sense of city residents. After years in which rates of homicide, armed robbery and killings by police fell, the numbers shot up again in the first six months of 2016. Violent deaths are up 43 per cent in June of this year compared to last. That is unlikely to have much impact on the tourists and athletes who come for the Olympics, because the government has deployed 82,000 personnel, including police, armed forces and private security guards, to keep visitors safe.

But the deterioration is grim news for the people who live outside Rio's fanciest quarters, both because of the risk they face right now, and because of what the return of the regular volleys of gunfire says about the fate of Rio's grand experiment in policing and public security.

Residents react during a shootout involving police and suspected drug traffickers at the Complexo de Alemao slum in Rio de Janeiro on June 27, 2007. Police killed at least 18 suspected drug traffickers in the massive operation.

RICARDO MORAES/ASSOCIATED PRESS

An ambitious experiment

Rio's violence problem began in the late 1980s when gangs with their origin in prisons began to take control of the drug trade. They based themselves in the favelas, areas where the state had little presence and had traditionally shown little interest in the well-being of residents. By the mid-1990s, there were whole swaths of the city that were fully under the control of autonomous armed groups – an extraordinary situation that came to seem normal.

When police entered at all, it was in brief, fiercely violent raids that produced high numbers of casualties. The rest of the time, the fate of people who lived in the favelas was determined by the nature of the particular gang that controlled their area: some directly preyed on the population, while others set up mini-states where the gang boss administered an authoritarian version of law and order, with punishments brutally and capriciously handed out.

At the same time, the gangs fought each other for territory, trapping civilians in the crossfire. It was a vicious and entrenched cycle. Violence spilled out across the rest of the city too, of course, but there was a vastly higher rate of death by violence in favelas.

Finally, in 2008, a handful of senior officers convinced the state government it was time to try something different, and they launched a program known as Pacification Police Units, or UPP in its Portuguese acronym. The idea was that a new cadre of officers, trained in community policing, would go into the favelas, and stay.

It was piloted in a handful of small communities. First an elite squad went in, with lots of warning, giving the drug gangs time to flee – which they did. Those who stayed but had weapons were given the chance to turn them in. Then the new unit set up shop. Officers walked through the community on foot patrols, they got involved in conflict resolution, they coached soccer teams.

Police bonuses were tied to reducing the number of homicides and robberies (rather than rewarding cops for killing suspected criminals, as was once the policy). UPP officers dialled back on policing the drug trade – not seeking to eliminate it, but hoping to remove the territorial occupation.

The second prong of the strategy was that, alongside the police, the state moved in with a battery of social programs – everything from health clinics to daycares to garbage collection – bringing the community into the fold of the larger city.

The fall in violence was immediate, and stunning. "People looked at the statistics and it was like we were the Messiah," says Robson Rodrigues, a retired police colonel who commanded the UPP project from 2010 to 2013.

A police officer salutes the Brazilian national flag atop the Alemao hill after invading the slum in Rio de Janeiro on Nov. 28, 2010.

SERGIO MORAES/REUTERS

After so many years of a dire status quo, there was no small amount of euphoria over the early success of the UPP, and Rio's project attracted attention in violent cities across Latin America. The push to expand the program was swift: There were seven UPPs when Col. Rodrigues took over, and he was under orders to install one a month – up to 40, by 2014, when the World Cup would come to town.

Now, however, eight years into the experiment, no one heralds the UPP any more. The project, like everything else in Rio, is flat broke, and has lots its political patrons. It's also lost much of the territory it reclaimed.

"In you asked me back in September, 2015, I still thought it was possible to save the UPP – I would have said yes, if the government reinvests and stops traditional policing tactics," said Silvia Ramos, who heads the Centre for Security Studies and Citizenship at Candido Mendes University in the city. "Two months ago, I would have said, 'Yes, but it will be difficult.' Today I say, 'No – it's not possible any more.'"

Virtually all of the territory claimed for the state through the UPP has once more been ceded to the gangs, she said – either overtly, or by police and traffickers tacitly agreeing not to confront each other.

Police officers stand in line during the inauguration of the UPP in Rio’s Rocinha slum on Sept. 20, 2012.

RICARDO MORAES/REUTERS

What went wrong?

The causes of the failure of the UPP are numerous and interconnected; some have their roots in dark parts of Brazil's history and others in the unprecedented confluence of crises that grip the country now.

First, it's incredibly difficult to change the culture of a police force, Col. Rodrigues observes with a sigh. Rio needed to take a police force that was created in the era of the military dictatorship, when "maintaining order" was done with repression, and convince officers who viewed the community as adversaries – where everyone is either in a gang, tied to a gang or hiding information about a gang – to instead see that community as people they serve and protect.

Rio didn't invest nearly as much time or money into recruiting new officers and training them well, as it needed to, Col. Rodrigues says. The majority of police, poorly paid and lacking resources to keep themselves safe, never embraced their new job, and the communities, steeped in years of brutal conflict, weren't convinced.

Then, the second prong of the strategy – the social services – arrived only in fits and starts or not at all. Some clinics and roads were built. Community centres were opened. But then no staff was hired for community centres or libraries. Garbage collection was erratic, sanitation hook-ups never came at all.

It's a something of a mystery, Prof. Ramos says, why the state failed at such an obvious thing. "They only ever envisioned driving the traffickers out, but nobody thought about the next day," she says. A recent study from Stanford University found that the breadth of the social component factored heavily into how much a UPP brought down violence in a given favela, and was "critical" for the policing effort to succeed.

This issue of credibility and state commitment became increasingly important as the police began to lose public trust. There were shootings, extortion and harassment – UPP officers used their foot patrols to do near-constant stop-and-frisk searches that people loathed.

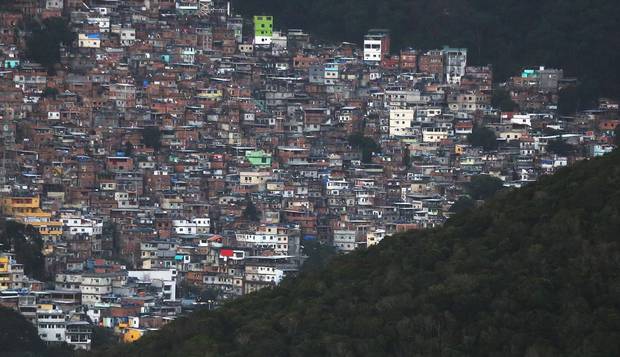

The Rocinha favela, seen from above on July 31, 2016.

MARIO TAMA/GETTY IMAGES

And then in September, 2013, a bricklayer named Amarildo de Souza from Rocinha, the largest favela, disappeared – and was eventually found to have been tortured to death by officers from the community force, who thought he had information on drug traffickers (whom they weren't meant to be pursuing in any case).

"Amarildo's death was catastrophic for the UPP project," says Col. Rodrigues. "It takes a long time to build legitimacy – but you lose it very quickly." Many people turned against the police after the de Souza case, and most were indifferent at best, he said. They certainly weren't going to help the project succeed.

At the same time, the UPP forces were stressed: After starting off in small and relatively "easy" communities, the force went into Complexo de Alemao, a collection of 22 favelas that sprawl together over low hills in the northwest of the city, near the international airport. It's home to at least 100,000 people, and was under the control of the Comando Vermelho, the most violent and confrontational of the gangs.

The UPP wasn't intending to tackle Alemao, but, in 2010, the gang came out of the favela to confront the state, engaging in shootouts with police and setting buses on fire around the city. This prompted a massive military occupation in return – which was transitioned to a UPP 14 months later. The next year, in 2012, a UPP was set up in Rocinha (pop. 120,000), which lines one edge of Zona Sul, the area that would soon fill with World Cup visitors.

Cable cars move along, seen through a window pierced by bullet holes, on July 24, 2012, at a police station used by the UPP in Rio’s Complexo do Alemao slum.

FELIPE DANA/ASSOCIATED PRESS

The mission in Rocinha was successful, at first, but the UPP never really took in Alemao, says André Rodrigues, an expert on public security who has studied the UPPs for the past six years.

"The occupation of Alemao was simultaneously the climax of the UPP and the beginning of its decline," he says. "There was an immediate drop in crime, and huge visibility for the police – but they should have dug in and fortified, and instead they pushed forward [with other expansions]. They didn't have enough police or the infrastructure to do foot patrols."

The UPP project in Alemao never really moved beyond occupation, he says. When the level of violent incidents began to climb, police from specialized tactical squads were shipped in, replacing the ones with community-oriented training – and exacerbating the cycle of confrontations.

Ask people who live there and they have real-world examples of all these problems. Mariluce Maria, a 34-year-old artist who runs a program through which local kids paint murals across the favela, describes the sense of optimism when the government built a big flashy cable-car over Alemao, to ferry residents to the tops of the hills, and put in a couple of new roads.

"But we were hoping for basic sanitation – and that didn't come," she says. "And to this day there isn't a single secondary school in the whole complex." They got a new soccer field, but the UPP stationed officers right in front of it: So people stopped using the field, because they were afraid of getting caught in cross-fire that resumed before too long.

Then came the money crunch. The UPP material budget was being sponsored by Eike Batista, the flashy Rio billionaire, once the world's eighth-richest person, in a gift to the city. Mr. Batista went spectacularly broke in 2014, drying up his philanthropy.

Then Brazil's larger economic crisis began to bite the state of Rio. When oil prices plummeted, the state, which drew a huge chunk of its budget from royalties from offshore drilling, effectively went broke, too. This year, the security budget has been cut by 32 per cent; demoralized police are getting paid months late, if at all; and there is no budget for overtime to put extra officers in places with problems.

Prof. Ramos points out that the UPP got guns and vests to do foot patrols, but never got intelligence services. There was no wire-tapping or tracking of weapons shipments, for example. The security ministry never looked further than the UPP – it wasn't one part of a larger strategy for improving safety in the city, it was the whole strategy. Many problems were clearly visible after the first few UPPs were installed, but there was no monitoring and evaluation component to the program – so the problems were replicated in each subsequent UPP rolled out, Col. Rodrigues says.

A UPP officer patrols in Babilonia.

MARIO TAMA/GETTY IMAGES

While all of this was happening, the gangs were watching. The major criminal leaders left the favelas before the UPP came in, and decamped to other communities that didn't get "pacified," or to more outlying regions of the city with limited police presence. They kept up the drug trade, ceding the territory.

But not all the criminals, or all the weapons, were removed, says André Rodrigues. Young men without criminal records stayed behind, keeping their weapons hidden, at first. But as the police weakened, as the population ceased to support them, as the lack of reinforcements and resources became apparent – the gangs began to emerge from the shadows again, seeing how much of the vacuum they could get away with filling.

In Alemao, Ms. Maria says, people call them " sementinhos do mal" – the little seeds of evil, young men who join the gangs both because they lack other opportunities and because they enjoy the affirmation of masculinity that comes with strolling the street with an automatic weapon. "They're much more violent because they're not thinking strategically about protecting their business," the way a kingpin is, says Col. Rodrigues.

Silvia Ramos argues there's a degree of absurdity to all this – Rio isn't a drug production centre and its gangs are not major international crime syndicates like Mexico's Sinaloa Cartel.

"We don't have ethnic or religious conflict of some places, and we don't have international gangs like Barrio 18 of Central America," she said. "It's not a criminal syndicate threatening judges or bombing public places. These gangs exist just to sell drugs and confront the police, and it's mostly illiterate boys in shorts and flip flops – and we're losing the war against them. This is what makes us crazy – are we again saying as a city we're not able to confront these people?"

In this year’s security budget, UPP officers got guns and vests to do foot patrols, but never got intelligence services.

MARIO TAMA/GETTY IMAGES

What happens now?

The Stanford study found that killings by police would have been 60 per cent higher without the UPP; that figure rose 68 per cent, to 74 deaths, this June compared to last. Meanwhile whole swaths of Rio – in the north and west zones, that were poorer and more violent to begin with – never received a single UPP and there is no sign now that they ever will. These neighbourhoods have minimal police presence at present, Mr. Rodrigues says – and now that all forces are concentrated around the Olympic area through August and September, they have even less.

Talk to people in Alemao, and everyone is convinced: "The day after the Olympics are over, when the tourists are headed to the airport, they will shut down the UPP," says Mariluce Maria.

Col. Rodrigues says the UPPs won't leave – but they will remain with their control steadily eroding and the violence rising. Police do not have the money or the staff to reoccupy what they have lost, Prof. Ramos says, but they will stand on one road while the traffickers operate on the next one.

That's the best a commander can hope for at this point, to avoid open confrontation, she said – but in many favelas, including those around her middle-class neighbourhood, the more confrontational gangs are showing they aren't content to share the streets. "We hear rounds of gunfire in the night – it's them, saying, 'We're back.'"

Follow Stephanie Nolen on Twitter: @snolen

THE GLOBE IN BRAZIL: MORE FROM STEPHANIE NOLEN

Jessica says she’s black. Her cousin says she’s white. In Brazil, race is a confusing, loaded topic

3:03