In early July, the mysterious leader of the Islamic State in Iraq and the Levant appeared publicly for the first time in a videotaped address.

Dressed in a black robe and a black turban, his dark beard fringed with grey, Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi, dubbed the most dangerous man in the world, strode to a microphone to lead prayers in Mosul’s grand mosque.

His followers had just swept through Iraq, slaughtering opponents and plundering a central bank on the way to a stunning military victory. ISIL now controlled a large swath of Syria and Iraq, as well as Mosul, Iraq’s second-largest city. It had declared that it would henceforth be known as the Islamic State, a caliphate governed by sharia law, and that Mr. Baghdadi had taken on the mantle of caliph – a political and religious leader for all Muslims. Now, he addressed the historic “burden” that had been placed on his shoulders.

“I have been tested with this trust, a heavy trust, and been appointed as a guardian over you,” he told the crowd. And the battle had only just begun, he said. “If you only knew what reward, dignity, loftiness and honour lies in jihad … not one of you would sit back or remain behind.”

In that moment, Mr. Baghdadi cemented his position as the world’s most powerful Islamist militant, surpassing al-Qaeda leader Ayman al-Zawahiri in influence and completing a revolution that had been under way for nearly a decade. By declaring an Islamic state, he has done what al-Qaeda promised but never delivered, and shown that he has far more real power than the al-Qaeda leaders currently in hiding in the Pakistan-Afghanistan border region. He controls oil fields, hundreds of millions in looted cash, and a capable, well-led paramilitary organization of more than 10,000 followers.

U.S. President Barack Obama vowed this week to “degrade and destroy” the militant group. This is vital not just to control its influence abroad – but to guard against potential threats to the West. Mr. Baghdadi’s success has young recruits, including at least a dozen Canadians, flocking to the Islamic State’s black banner. Speaking from London this week, Prime Minister Stephen Harper said that the Islamic State “has the capacity of not just leading regional jihad, but becoming a massive terrorist training base for the globe.”

Although the Islamic State has so far deployed its Western passport holders in the fight for Syria and Iraq, security services are deeply concerned about the threat posed by the potential return of radicalized and well-trained extremists.

Eclipsing al-Qaeda

The leader drawing so many hopeful jihadists from around the world was born a Sunni Muslim in the Iraqi city of Samarra in 1971. He studied religion as a young man and is believed to have earned a PhD in the subject from a Baghdad university. He also claims to be descended from the prophet Mohammed, a requirement for someone claiming to be caliph.

At some point after the 2003 U.S. invasion, Mr. Baghdadi joined al-Qaeda in Iraq, which was led by the Jordanian militant Abu Musab al-Zarqawi. From 2003 to 2006, Mr. al-Zarqawi briefly seized the world’s attention in much the same way as Mr. Baghdadi has today, with spectacular attacks and brutal beheadings. His terrifying bloodlust, particularly his sectarian attacks on Shia Muslims, drew a reprimand from al-Qaeda leaders, who thought he was alienating potential sympathizers. Mr. Zarqawi ignored their warnings, recognizing that he was growing better known and more influential than the old guard, attracting money and recruits from all over.

But Mr. al-Zarqawi was killed in 2006 by an American air strike. Some time around that period, Mr. Baghdadi was arrested by U.S. forces. He was not seen as a major figure in the insurgency, but during his time imprisoned at Camp Bucca, a detainment facility in Umm Qasr, Iraq, he is believed to have expanded his network. Upon his release a few years later, he returned to the group, renamed the Islamic State in Iraq, and was eventually named its leader in 2010.

His timing was good: The Arab Spring and Syria’s spiral into civil war provided a perfect opportunity for the Islamic State of Iraq to re-organize and rebuild. For example, Mr. Baghdadi helped to create the Nusra Front in 2011, one of a number of opposition groups vying to overthrow President Bashar Al-Assad.

When Mr. Baghdadi announced that the Islamic State was taking over the Nusra Front in 2013, he was rebuked by al-Qaeda leaders who declared the merger invalid. But in a bold public stand, he said al-Qaeda “is no longer the base of jihad,” and that it had “deviated from the correct paths.”

“I have to choose between the rule of God and the rule of Zawahiri and I choose the rule of God,” Mr. Baghdadi said at the time.

“That really distinguished him,” said Kamran Bokhari, adviser on Middle East and South Asian affairs for Stratfor, a global intelligence company.

As the insurgency roiled in Syria, Mr. Baghdadi proved to be a shrewd organizer and planner. About a year ago, he recognized that Iraq under President Nouri al-Maliki was drifting further into sectarian division, an opportunity he could exploit, Mr. Bokhari said. In a marriage of convenience, Mr. Baghdadi recruited former Iraqi Baathists and members of the Iraqi military and spy services, according to Mr. Bokhari. Many of these men had lost their jobs after the U.S. decided to “de-Baathify” Iraq’s military. They gave him the organizational strength and the tactical nous that fuelled the group’s battlefield success over the last several months.

Mr. Baghdadi also appears to have a passion for accounting and annual reports, which the Islamic State has produced since 2012. In 2013 it published figures for the number of assassinations carried out, improvised explosive devices planted, checkpoints established, and suicide attacks. The Financial Times also cited figures showing that the Islamic State was taking in as much as $8-million a month by extorting businesses and residents in Mosul. Others have suggested its oil sales could be worth as much as $1-million a day, although Mr. Bokhari said he doubts the figure is that high.

“That’s the kind of money a state generates,” he said.

Mr. Baghdadi’s inner circle is made up mostly of former military and security officers, according to Iraqi analyst Hisham al-Hashimi, but he also has prominent roles for recruits from Saudi Arabia and Syria, and prominent fighters who are Chechen. Citizens of Britain, the United States, Canada and Australia have also featured in the group’s propaganda work on social media.

The diversity of those featured is likely intended to suggest a global organization, even if the Westerners are mainly used as low-level fighters or in media operations. Significantly, no Western Muslims are said to be part of the inner circle, but each passing week seems to bring news of more Canadians who have joined the fight, raising the spectre of a growing threat at home.

‘Come and join’

“Come and join before the doors close,” implores the man identified as Abu Muslim in his martyrdom video.

He speaks of hockey and camping and life growing up in Timmins, Ont., where he was known as Andre Poulin before he says he was born again as a Muslim fighter. “I was like any other regular Canadian,” he says in the video. Circulated in July, this slick appeal to the YouTube generation argues that all able-bodied Muslims are obliged to join in the jihad and get away from “Dar al Kufr” or a land of infidels.

Then the camera cuts away to the scene of his death, in which he runs headlong into a hail of bullets, as he and other Islamist insurgents lay siege to an airport in the Syrian desert.

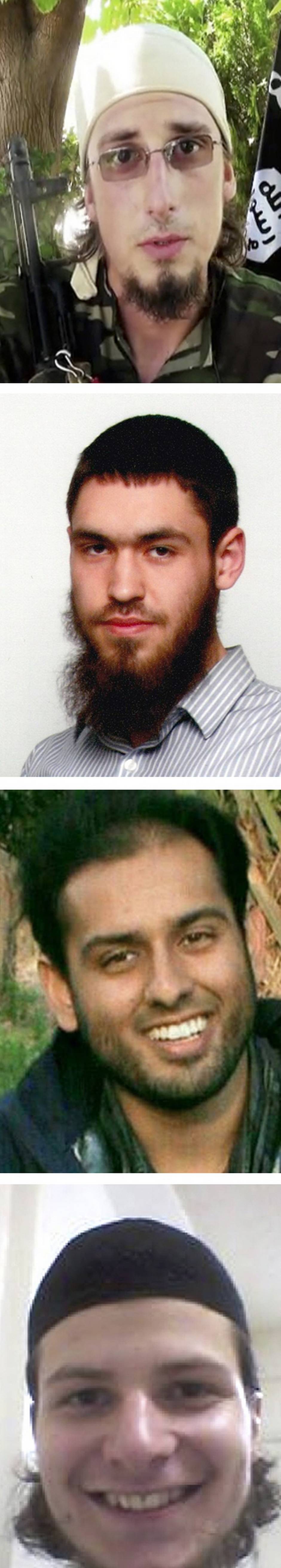

Like hundreds of Western recruits who have aligned with the Islamic State, Mr. Poulin was probably more esteemed for his passport and propaganda value than his battlefield acumen. Consider Salman Ashrafi, a married former Talisman Energy human-resources analyst from Alberta, who is said to have killed himself – and 46 Iraqi soldiers – by exploding a truck bomb. Or his fellow travellers from Calgary – Farah Shirdon, who appeared in a videotape promising to he would help ISIL bring death upon Canada, and Damian Clairmont, a convert, both of whom were also recently slain in Syria and Iraq.

Last week, Canadian officials repeated their official estimate that “about 30” Canadians are “suspected of involvement in terrorist related activities” in Syria, which would also include those who joined the Islamic State’s rivals, such as the Nusra Front. Yet Ottawa’s figure may be too low. U.S. representative Mike Rogers, chair of the House Intelligence Committee, told cable news outlets last week that “several hundred” Canadians or “as high as 500” had flocked to Syria. To put that in context, Germany and Britain each said they believe 400 to 500 of their citizens have joined the fighting in the region, while various officials suggest anywhere from 12 to 100 Americans have joined the Islamic State.

At least five Canadians have been killed while fighting in Syria and Iraq. Generally in their 20s, they came from all walks of life. Federal officials say the struggle to investigate and prevent domestic recruitment is a nebulous cat and mouse game, given the unpredictable nature of radicalization. They say they have enormous difficulties identifying or catching prospective terrorist recruits before they depart. And once they do get outside, there are few levers Canadian police can use against them.

The Mounties are examining new measures to curtail radicalization in Canada. They are also running a “High Risk Travel Case Management Group” that is said to be “disrupting attempts to travel” by would-be terrorists. What that actually involves is unclear. According to sources, suspected Canadian extremists have lately complained about government officials taking away passports.

In August, the country’s top spymaster wrote a piece in The Globe and Mail acknowledging that Canadian Islamic State fighters are a threat on our soil as well as abroad. There is a “very real prospect” that they would use their terrorist training to attempt violent acts in Canada.

“Europe has already suffered such an attack, where a French citizen and ‘returnee’ from Syria went on a shooting spree in Belgium and killed a number of innocent civilians,” Michel Coulombe, director of the Canadian Security Intelligence Service wrote.

“Even if a Canadian extremist does not immediately return, he or she is still a Canadian problem.”

Hashtag terrorism

The Islamic State’s rise has been marked by brutality. The recent decapitations of U.S. journalists Steven Sotloff and James Foley are but two examples of a conscious harking back to acts of seventh-century warfare, but with images recorded and disseminated via 21st-century smartphones as a tool for terror, fundraising and recruitment.

The Islamic State propaganda machine is a sprawling endeavour, operating in multiple countries, using multiple mediums and propagated by thousands of low-level volunteers and supporters. It typically pushes out gruesome footage of executions or car-bombs, as well as somewhat more pleasant missives, such as a recent testimonial-style video on the various benefits of living in the Islamic State that features interviews with fighters from Morocco, Indonesia, Finland, Tunisia, Britain, Belgium, the United States and South Africa.

Beyond videos, the Islamic State propaganda teams have designed and disseminated a wide variety of digital banners that now grace the Facebook and Twitter profile pages of their supporters. Such banners tend to centre on the black flag emblem, but others also show images of the burned and mutilated bodies of Islamic State-executed enemies, or still shots of fighters destroying forbidden crops, such as tobacco or marijuana.

The content spreads quickly, making it virtually impossible to delete entirely. The accounts usually amass a few hundred or a thousand followers before they are shut down – only to pop up again under slightly different names.

“These guys have become the boogeymen of the world right now and they know that and capitalize on it,” Mr. Bokhari said.

The social media techniques employed by the Islamic State are not entirely different from those of other jihadist groups. However the Islamic State media machine appears to exceed all previous iterations in scale, variety and sophistication. The group’s videos have a substantially higher production quality than other groups, and feature near-perfect English translations and subtitles of Arabic content, indicating a large number of native English-speakers within the group’s propaganda arm.

“There’s guys out there listening and absorbing that propaganda, that radicalized vision,” said Linda Robinson, a senior international policy analyst at RAND Corporation. “I think everybody’s awakened to it pretty dramatically now – it seems to me like it’s a night and day situation, where people have suddenly realized that this is the new al-Qaeda.”

In truth, the Islamic State is a major threat to al-Qaeda.

“The Islamic State has now emerged as the world’s second jihadi superpower, and possibly the dominant one,” J.M. Berger, a U.S. based researcher, wrote in Foreign Policy this week. “And it wants what al-Qaeda has – global terrorist credibility and the respect, support and loyalty of the world’s jihadi organizations.”

Yet, Mr. Berger writes, while Mr. Baghdadi’s group has won pockets of support from terrorist leaders in Gaza, Afghanistan, Indonesia and elsewhere, “core” al-Qaeda retains the support of its heavy-hitter franchises in Yemen, Somalia and North Africa. The discord threatens to divide the global jihadist movement.

“It’s a permanent rupture, because al-Qaeda’s looking bad. These guys [the Islamic State] are taking over and getting people to defect from al-Qaeda all over the world,” Mr. Bokhari of Stratfor said. “They’re the main show. Zawahiri’s worry is that he’s looking pathetic. He has nothing to claim. These guys openly say ‘You claim to be a leader but you’ve been hiding for over 10 years.

“This group eclipsed al-Qaeda years ago, but nobody paid attention. It wasn’t evident, but now it is.”

For the moment, the Islamic State’s operations have focused on holding territory, installing sharia law and establishing a caliphate over an area the size of the U.K. But their ambitions, as revealed in the re-drawn maps of the world they distribute on social media, are much grander. Their aim is a caliphate extending from North Africa to South Asia.

The more realistic threat, according to Western security officials, is that ISIL fighters will return to cause trouble in their homelands. Aaron Zelin, a researcher affiliated with the International Centre of the Study of Radicalisation and Political Violence, said any plots or attacks in the West are now more likely to emanate from the Islamic State than al-Qaeda.

The rivalry between the groups intensified this week as al-Qaeda announced it was opening a branch in India and ISIL responded by posting leaflets in the city of Peshawar, where al-Qaeda leaders are believed to be hiding, announcing their caliphate extends to the Pashtun lands.

Division among violent extremists may be beneficial, or it may not, Mr. Berger said.

“The infighting could also work against us, if the competing factions decide that the best way to settle things is by proving who is the biggest, baddest and most brutal terrorist.”