It took him four tries.

The first time Fernando Avila left home in El Salvador in the care of a coyote, he was caught in Mexico, detained, and sexually molested in a jail. He was 14. On his next attempt to go north, he was again caught in Mexico and deported. On his third try, he was stuffed in a bus full of other kids in Guatemala; the driver was inebriated and went off the road, and a five-year-old and a 16-year-old travelling with Fernando died that night. He escaped with a head injury; he was hastily bandaged in a hospital, and deported.

Then, last May, his extended family pooled all the money they could muster, for one last try. They had to get him out; they were certain that he was out of time, and the gangs would no longer spare him. They got him into Mexico. There he waited for months, stuck in a small house in the centre of the country while relatives in the U.S. worked frantically to earn enough to pay for the rest of the trip. Finally, they sent cash, and the coyote drove him to the banks of a river, loaded him into an inflatable black-and-orange dinghy, waded into the water and towed him across the Rio Grande.

Fernando climbed out in the shallows, walked up to a truck parked nearby, and said to the border patrol agent at the wheel, Necesito ayuda. I need help.

It was Sept. 18, 2016.

A desperate bid to flee the gangs

A year before, The Globe and Mail told the story of Fernando's family and their frantic efforts to get their child out of El Salvador, where 25 people were being murdered each day in a country with the same population as Toronto. He became one of the tens of thousands of unaccompanied children who fled Central America to try to cross into the United States and make a claim for asylum. Parents entrusted their children to human smugglers who took them through territory controlled by drug cartels, where they risked kidnapping; sexual assault; forced labour in narcotics production; death by dehydration, exposure and drowning; even abduction for organ theft. The trip is monstrously dangerous, and the only thing worse is staying at home.

"If I send him, he may die," Irma Avila said then. "But if I keep him here, he will die."

(The Globe has changed the family's name, because they risk violent reprisal in El Salvador for talking to a journalist, and because Fernando is now at risk in the United States.)

Fernando has, for the past four years, been targeted for forced recruitment into one of the gangs that rule swaths of El Salvador and are engaged in what is, in effect, a civil war, between each other and against the government. Members of the Barrio 18 and the Mara Salvatrucha 13 battle continuously for territory and then kill each other in an unending cycle of retribution, while the state ventures in and out of the fray with periodic crackdowns, carrying out extrajudicial killings and stoking the violence. El Salvador had the highest murder rate in the world last year. The gangs rely on young people, because they constantly need to replace dead members and because criminal penalties for minors are lower than those for adults. Many young men join up – because life in the maras seems like the best option in a desperately poor country, and because they don't have a choice.

The Avilas wanted to keep Fernando, who dreamed of being an engineer, out: Their shy, dreamy boy would be dead within days with the Barrio 18, they were sure.

When it was published in 2015, the Avilas' story helped to illuminate a crisis that was mostly being viewed through the lens of a swamped U.S. immigration system, flooded with Central Americans fleeing violence. The Avilas' dilemma helped to explain why parents were making a choice, the dangers of which they knew full well, to send their children away. And it also demonstrated how the U.S. has outsourced its border control to Mexican authorities, effectively moving the frontier 3,000 kilometres to the south, in an effort to choke off the flow of Central Americans.

The Globe has since kept track of Fernando, and other young Central Americans repeatedly attempting the journey to the United States, and this story was originally intended as an update on their progress, as they reached America and began new lives as refugees, far from parents and siblings, but finally safe.

Now the election of Donald Trump to the U.S. presidency, and the executive orders on immigration and refugees in his first days in office, has thrown their future into question once again.

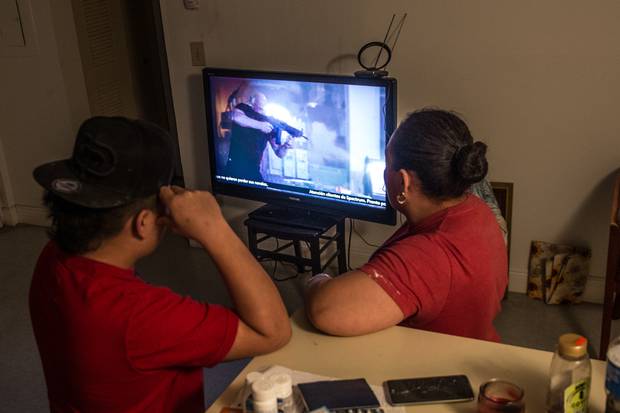

Fernando and his aunt watch TV. In order to release Fernando from a youth detention centre, his aunt had to identify herself to the Department of Homeland Security, meaning authorities will know where to find her if they decide to deport her.

Fernando and his cousin rest after a day on the job. He works day and night shifts drywalling for a renovations crew with other undocumented teenagers.

An extended family in peril

Fernando always imagined that when he got to America, he would go to school, and learn English, and work to start helping his family pay back their debts. He would go to court – "a real court, one that functions, not like El Salvador" – and tell the judge his story, and be granted asylum. And after a few years of studying and working, he would become a citizen. He could sponsor his little sisters, get them out of El Salvador, before they were old enough to attract the eye of a gang leader; he could perhaps go to college.

Instead, he finds himself in a position nearly as precarious as the one he left behind. He is working – drywalling, night shifts doing renovations in a national drugstore chain, on a crew with other undocumented teenagers. He earns $80 (U.S.) a day, and sends half of it home to his mother. He is waiting for a court date to make his initial case for asylum. But he is no longer sure if the U.S. will admit refugees, no matter how good their case, or indeed even if he will be permitted to proceed with his claim. It's a reasonable fear: Immigration lawyers and refugee-rights groups have no idea what rules apply now either.

If, instead, he is detained and deported to El Salvador, he will, in the best-case scenario, be a target for redoubled pressure and harassment from the gangs: He defied them in leaving, and because he went to the U.S., they will see him as a flush source of funds. There is also a significant possibility that he will simply be killed: Researchers tracking undocumented Central American children who have been deported in the past three years have a tally of more than 100 migrants who were murdered by gangs on their return.

And in the meantime, Fernando has imperilled his entire extended family . In order for him to be released from a youth detention centre by migration authorities, his Aunt Helena had to identify herself to the Department of Homeland Security, prove that she could act as his legal guardian, supply her address, and respond to follow-up communications. That system was created to protect unaccompanied minors who were detained at the border. But it has had the effect of making Helena, who has been in the U.S. working as an undocumented migrant for the past five years, and by extension her whole family, known to and immediately locatable by Homeland Security.

The administration of former U.S. president Barack Obama had an unwritten policy that it would not target such family members, acting as guardians for asylum claimants, for deportation. Mr. Trump, with his pledge to deport three million of the people he calls "illegals," has made no such indication. With her job in construction in Florida, Fernando's Aunt Helena is the sole source of support for both her ailing mother, and her own two children, back in El Salvador; she has also been the emergency source of funds to rescue teenagers in the extended family who were targeted for extortion and kidnapping by the maras. If she is deported – from the house whose address she gave to Homeland Security, where she must by law stay if Fernando is to pursue asylum – all of that will be lost.

"I thought twice about it," she said, when the call came telling her to come and register to claim him. "But really I had to do it. So I did.

"Of course, with the documents I had to provide to go and get him, they could come for me," she added. "Any time they want."

A precarious perch in America

I first met Fernando in the parking lot of a migrants' centre run by the government in San Salvador in August, 2015. I had already spoken to his parents earlier that day: Irma and Eduardo had been sitting anxiously in a row of hard chairs, waiting for the buses full of kids to roll into town from Mexico. They told me how crushed they were that Fernando was caught, after the effort it took to raise the money to send him – and also how profoundly relieved they were that he was on his way back, because they had been sick with worry since the day they handed him over to a coyote on a bicycle a few weeks before.

The Avilas were self-contained, self-possessed, and immensely dignified. I talked to them for about 45 minutes, and then moved on to other families. But a couple of hours later, I happened to be in the parking lot as Fernando arrived: I saw him seek out his family, his face a mix of relief, happiness, and the raw awareness that his return was a disaster. I watched as his tiny sisters wrapped themselves around his legs, as his mother hugged him hard, and then as Fernando's studied bravura fell away when his father, no taller than he, wrapped an arm around his shoulders. The boy began to weep, and then his father did, too, and the little girls froze, eyes enormous, at the sight.

I went on to spend a fair bit of time with the Avilas, including a visit to their home in a town called Aguilares, where I had a brief but thoroughly terrifying taste of what life is like living under the maras. The family talked me through the finances – the money lenders, the network of relatives, the "three tries" package they bought to try to get their son over the border. Irma sent me word when Fernando left for his second try a few weeks later, and I waited for news – it wasn't good; he was caught again. Once more, his mother went to meet the bus from Mexico, so glad to have him where she could see him, and more desperate than ever to send him away.

It was more than a year before I heard good news from Irma: In November she sent a message that Fernando had made it to the United States, been detained, and then released to make an asylum claim. He was with her sister in Miami, and they were all jubilant.

I kept my reservations to myself, but I was more cautious: Just 40 per cent of Central American children's asylum petitions are granted, and almost all of those from children whose families are able to pay a lawyer. (Only two per cent of Central American adults are granted refugee status.) It didn't seem at all certain to me that Fernando would be allowed to stay in the United States. While no one disputes that Central America is convulsed with violence, and that young people are its disproportionate victims, refugee status is, in theory, available only to someone who can prove they are being targeted as a member of a "group" – because they are gay or transgender, or a member of a religion or ethnic minority, or, in a growing body of claims, a woman. Gang membership is not considered a basis for "persecuted group" status, and neither is forced recruitment.

But I interviewed immigration lawyers who told me that Fernando's case sounded relatively strong, and that, at a minimum, he would likely be able to stay in the U.S. for several years as he exhausted all avenues for appeal. Those would be years in which he could pay off some of his family's monstrous debt, and years in which he would be safe.

And then, 51 days after he arrived in the U.S., Donald Trump was elected the next president.

Four years ago in El Salvador, Fernando got threatening calls from gang members saying that they would kill him if he didn’t join them.

Persistence, and mounting debt

Barrio 18 first came for Fernando in 2013. It started with the standard mix of intimidation and enticement. When Fernando resisted, it escalated to phone calls at all hours of the night: "We will cut your tongue out. We will cut your ears off. We will dig out your eyeballs. We see you walking to school. We are coming." A car with tinted windows crept along beside the path where he walked to class each morning. There was no help to be had from the police, who almost never investigate forced recruitment – and if the gang knows you have reported them, it means certain death. So Fernando stopped going to school.

Then a childless uncle living nearby, who is a welder and relatively prosperous, began to get phone calls, ordering him to pay $1,000 or else Fernando would be killed. He paid, and the threats stopped for a while.

Then Aunt Helena, in Florida, began to get the calls, too. If Fernando wouldn't join the mara, they would make money off of him other ways. In recordings she made of the calls, the gangster's voice is harsh and snarling, as if to mimic the dogs that bark in the background. "Send it," he says. "You know we don't play." They said they would put a bomb in her elderly mother's house, that they would kidnap her daughter, murder Fernando.

From Helena, they wanted $4,000. She pleaded that she was sick and not working – on the recordings her voice is high with anxiety, but she is not cowed. "Who are you?" she demands. "What's your name?" She tried to buy them off by sending small chunks of money here and there, precious dollars intended for clothes and school fees for her own children. "I fed them," she told me, bitter and rueful and resigned all at once, with the euphemism they use in El Salvador for extortion payments. "You think, 'Hell, I'm going to work all day to feed these bastards.'"

After Fernando was deported the second time, the harassment grew more intense: Sharp-eyed mara spies noted his absence; they saw his attempt to flee as defiance, and they knew the family had scraped together the money to send him. They stopped Fernando in the road near his home, and told him he must join. He later told me that he had tried to answer vaguely. "I knew it was just a matter of time until I would have to go again."

Staying, giving in and joining the Barrio 18 so that all of this would just stop: He couldn't face it. "It's crazy – killing someone and then someone kills you," he said. "They don't have feelings – for them it's just fine to kill people. But not for me."

The Avilas had purchased a three-attempt package from the coyote, but he refused to honour their third try without a new payment – and it wasn't as though they could call up the police to complain. (El Salvador's government downplays the role of the country's public-security crisis in driving the flood of children northward, but does little to stop the human-smuggling pipeline.)

The family, frustrated that Fernando had twice been caught in Mexico, decided they would try someone new: It took until May – months that Fernando largely spent inside the family's three-room house, trying not to attract any attention – for them to raise the $4,000. That was the trip during which the van crashed in Guatemala.

In June, less than a month after he came back, with his head a scabby mess and his memory still blurry, his parents sent him again: "I was scared, thinking about the accident and hoping nothing would happen." But his grandmother urged him to leave – "She said, 'You have to go before something happens to you here.' " The Avilas went back to the first coyote, and tapped the whole extended family to come up with the first $1,000 as an initial payment. When he set off, he had company: A cousin came, too – a girl his age the gangs had been demanding payments for – as did a friend who was being forced into a sexual relationship with a gang leader. They did the first part of the journey, into Guatemala, themselves – Fernando knew the way well, by that point. In a bus station there, the coyote's guide picked them up in a car.

This journey, he told me, was better. It wasn't a succession of days spent climbing into and out of vans, walking through the underbrush to skirt police posts or borders. The guide was less harsh than the ones who took him before, and Fernando felt safer than he had on previous trips. They crossed into Mexico at La Mesilla, then took dirt roads up to Tuxtla, the capital of the state of Chiapas. When they encountered Mexican police posts, the guide just straight-up said the kids were Salvadoran migrants; clearly, Fernando said, someone important had been paid, because they were waved through. From Tuxtla, they took the highway north to Pachuca in the centre of the country.

And there they waited – nearly three months – while his Aunt Helena and her husband and another aunt worked and scrimped so that they could send the next $1,000. Finally, one night near midnight, the guide hustled Fernando and the girls into a pickup truck and they drove up to Reynosa, a town where the Rio Grande forms the border with Texas. For the next two days, the teenagers dozed in preparation for another nighttime journey. And then the third day, they were woken in the late afternoon with the words, "Today you're going to cross."

Fernando says he wasn’t scared when he made the Rio Grande crossing that brought him to the United States, because he was caught up in the excitement.

Grateful for 10-hour work shifts

The river was far narrower than Fernando had anticipated. He can't swim, and neither could the girls, but he tells me he wasn't scared as he clambered into the little boat and the guide slipped into the water to start pulling the rope. "I was just thinking, 'I'm going to cross' – I was just excited." There was still enough light when they got out that they could make out the truck belonging to la migra, the border patrol. The Mexican trafficker stayed nearly submerged in the water, but whispered for them to walk toward the headlights.

The agents in the truck were kind, Fernando says, and so were the next ones, at the detention centre in McAllen they drove them to. "They asked why I had come, and I told them about the gangsters." They let Fernando call his aunt. The family had heard from him a few times on the road, when the coyote guide let him to call to say he was safe. By now, their anxiety was feverish.

"When he called – I was very happy, because he'd been through the most dangerous part," Helena said, about the region around the border crossings, which are controlled by narco-traffickers who routinely prey on migrants, robbing and raping them, or worse. "That's where they kill them, that's where they make them suffer the most – so that was past."

Homeland Security held Fernando there for a month. He lived in a dorm full of other kids, went to school in the days, and says it was a nice place. The U.S. authorities were generally kind, he says, and spoke to him in Spanish, and were vastly more gentle than the Mexican police who had three times arrested him.

When his paperwork was cleared, a staff member took him on his first trip on a airplane (an experience he found unpleasant) and he landed in Fort Lauderdale to begin his new life.

He went to live with his Aunt Helena and her husband; a few weeks later they were joined by another teenage cousin who made it across the Rio Grande. The family rents a ground-floor apartment in a row of nondescript townhouses in a neighbourhood of strip malls, pawnshops and nail salons. The boys share a room with two single beds on the floor; in the main room, there is one small couch, one kitchen chair, and a TV where they watch Mexican and Venezuelan telenovelas when they get home from work. When he's alone, Fernando writes and sketches in a journal: He muses about God always giving him one more chance, about destiny and whether it's determined – and writes about how much he misses Wendi, a girl back home.

Fernando's prize possession is an LG smartphone, which he uses to call his family in El Salvador through WhatsApp. That's the worst part: how much he misses them all. He steels himself not to weep when he calls. In any case, his sisters badger him to send money for dolls, so that makes him laugh.

He works 10-hour day shifts, or slightly shorter night ones, drywalling; he wants to get more skilled and move up the crew hierarchy so that he earns more. He comes home from work caked in white powder, and aching, but he's glad to have work. He would like to be going to school – maybe he could do night school – but he's tired and his erratic schedule makes it difficult. His Aunt Helena had to badger the bosses in the construction crew she has worked on for years to hire him; they prefer to avoid the scrutiny that comes with hiring kids, even if they're cheap.

His asylum paperwork sits in a stack of envelopes in a plastic shopping bag on the narrow kitchen counter. There is a packet that Homeland Security gave him when they released him, listing pro bono legal resources that could help with an asylum case. But it is in English, and no one in his family had read it. There was also a letter, ordering him to appear in court in December. Fernando didn't go: The letter was in English and no one in the family found someone to translate it in time. Standing in their kitchen, I felt a flash of disbelief, and I asked – after all this, the coyotes and the cartels and the debts, you missed your first court appearance because no one tracked down someone who could read a letter?

No one met my eyes. They were tired – bone weary from years of manual labour and constant anxiety about deportation – and they had no experience of a government that functions, or might possibly function, in their interests. We saw different things, the family and I, when we looked at that letter.

The weirdest thing, Fernando told me, about America, when he finally got there, was that everyone spoke English, all the time. He'd never really thought about how that would feel. The language, the daunting unfamiliarity, means he goes from work to home and back; what he sees of America is through the dirty window of the van, or the venetian blinds of the apartment.

Executive orders, vast backlogs

The right to claim asylum was set out in the United Nations 1951 Convention and Protocol Relating to the Status of Refugees, and the right of those with a "well-founded fear of persecution" to seek sanctuary in the United States has subsequently been enshrined in several acts passed by Congress. Mr. Trump's executive order freezing refugee claims for 180 days is the most substantive move to restrict that access. It has left organizations that assist refugees and migrants scrambling to understand the legal implications, and braced for what may come next.

Asylum seekers such as Fernando are following a process well established in international law, notes Tammy Alexander, who works on immigration policy in Washington with the Mennonite Central Committee, an organization that assists asylum seekers across the U.S. But there is nothing in the law that obliges states to grant refugee status.

Trump executive orders so far have called for the mandatory detention of refugee claimants (so Fernando would remain in detention for the years it takes to process his claim), Ms. Alexander notes. However, a number of lawsuits brought by refugees during the Obama administration obliged the government to release them, so it is unclear if or how that order will be followed.

The executive order talks about immediately adding 10,000 Immigration and Customs Enforcement officers and building more detention centres – but, she notes, those centres are already housing record high numbers of people, and ICE is contracting space in jails to try to accommodate them. There is already a years-long backlog in processing cases; moving swiftly to deport claimants will mean hiring thousands more judges, which was not included in the order.

Meanwhile, people such as Fernando's Aunt Helena are now at enormous risk, she says, simply because they followed the law.

On Friday, the Associated Press reported that a leaked White House memo shows President Trump is considering mobilizing 100,000 National Guard troops to round up undocumented migrants.

Eleanor Acer, who works on refugee protection for the organization Human Rights First in Washington, says that, even without an outright ban on refugees, her organization is expecting hasty processing of claims – "rocket dockets" – without legal counsel or time to gather evidence.

But she believes that refugees will continue to be able to make claims in the U.S. "The Trump administration could look to find loopholes or ways around the law or ways to evade U.S. obligations under the Refugee Protocol but that doesn't mean that at the end of the day they will be successful," she says. "The odds of the U.S. withdrawing from the refugee convention drafted in the wake of World War II, which the U.S. was highly influential in drafting – I think that's highly unlikely."

Ms. Acer pauses, and notes that her comments reflect a surprising degree of optimism in the wake of the executive orders. "That would be extraordinary, if they did that. The Refugee Protocol is the cornerstone of international law. Then there's no rule of law globally, if they did that."

One of Fernando’s drawings reads: ‘Mom, I miss you.’

'You want the best for your family'

On the day of Donald Trump's inauguration in January, I flew to Fort Lauderdale to see Fernando. He waited for me on a corner near his house, wearing a pressed-crisp flannel shirt buttoned all the way to the top and a black baseball cap flipped backward. At the incongruous sight of him, so far from the red dirt road lined with bougainvillea where I last saw him, I jumped out of the car and gave him an entirely unprofessional hug. He endured it with an awkward 16-year-old grin.

We went to Denny's, where a waitress in a spectacular blond wig called everyone "honey" and kept trying to refill our giant cups of soda. On the TV screen above us, Mr. Trump in his long blue overcoat strode past banks of flags.

Fernando had a tiny patch of whiskers on his chin; his nails were bitten to the quick.

He isn't much of a talker at the best of times, and he was ill at ease in the diner. Haltingly, he talked about how much his family owes – $13,000 all together – and how desperate he is to improve his drywalling skills so he can earn more. His eyes filmed briefly with tears when he talked about the serious risk that his family will lose their house. A lawyer to handle his asylum case, meanwhile, will cost $6,000.

Later I joined his family in their apartment, and when he was out of the room, his Aunt Helena said gently that Fernando is terrified that he will be sent home, before he has been able to pay off his debts.

At work, she said, everyone is talking about Mr. Trump, about whether he really would target and deport all undocumented migrants, and even those who are claiming asylum like Fernando.

"If I'm deported – my mother will die," she said. There is no way, she said, that she could earn enough to cover her mother's medication and care costs with the wages she would earn in El Salvador. "Trump says they're going to deport everyone. Then, what are we going to do? I'm scared. We're all so scared."

Mr. Trump popped up again on the muted television beside us. Helena bristled. "If all of us immigrants are gone, what happens to the U.S.?" she said in rapid-fire Spanish, making a dismissive gesture toward the screen. "We're the ones working here, working like teams of oxen."

A little later, Helena softened again, and said it would all have been worth it – the debts and the threats, even if she is deported – if Fernando gets refugee status and the right to stay. "I don't have papers, I will never have. They could come and get me. But he will have it. We're going to get a lawyer and he will have papers – so it was worth it for me. Because you want the best for your family. If he can make something of himself here, I'll be very glad."

Stephanie Nolen is The Globe and Mail's Latin America correspondent.Follow her on Twitter: @snolen

PILGRIMS' PROGRESS: MORE FROM THE GLOBE AND MAIL

THE GLOBE IN LATIN AMERICA: MORE FROM STEPHANIE NOLEN

From the archives: Take the illegal migrant’s path from Guatemala to Mexico