Current emission-cut pledges established in the prelude to the Paris climate talks aim at limiting surface temperature warming to 2 degrees Celsius over the preindustrial era by the end of the 21st century. In the final leg of the Paris conference, a growing number of countries, including Canada, are calling for an even more ambitious target: capping temperature rise to 1.5 C.

But even capping warming at 1.5 degrees will not stop the environmental consequences of climate change. Here's a look at what effects different surface temperatures might have on the Earth and what it'll take to mitigate the long-term effects of climate change:

+1.5-degrees Celsius

Sea levels could rise to submerge land currently home to 27.4 million people in China, 3.6 million people in Bangladesh and 13.4 million people in Vietnam, according to projections by three scientists working for Climate Central, a non-profit organization that reports on climate science. In the United States, the homes of 7 million people would be under sea level. In Canada, 540,000 people would be affected.

Median local sea level could rise by 2.9 metres in the Vancouver area, above what is now the homes of 295,000 residents. In the Montreal area, the water level would go up by 2.7 metres, affecting 5,000 people.

The impact would be even worse in large Asian cities: the homes of 4.2 million people in Shanghai, 4.9 million in Hong Kong and 1.2 million people in Hanoi would be under water level.

Climate change is causing species in the temperate zone of the Northern Hemisphere to move northward or higher in elevation. At 1.5 °C, most trees and herbs would be at moderate risk from falling behind the shifting climate zones, says Hans-Otto Portner, professor in Integrative Ecophysiology at the Alfred-Wegener Institute in Germany.

In the Middle East and North Africa, heat waves for two weeks to 80 days, according to the World Bank.

Between 6-15 per-cent increase in diarrheal disease in the Middle East and North Africa. Increase in the incidence of morbidity associated with food and water-borne diseases in Beirut of 16 to 28 per cent. In South America, 5 to 13 per-cent increase in relative risk of diarrheal diseases. In Mexico, 12 to 22 per-cent increase in dengue-fever incidence.

+2-degrees Celsius

Sea levels could rise to submerge land currently home to 64 million people in China, 12.5 million people in Bangladesh and 25.8 million people in Vietnam, according to projections by three scientists working for Climate Central. In the United States, the homes of 12 million people would be under sea level. In Canada, 737,000 people would be affected.

Median local sea level could rise by 4.7 metres in the Vancouver area, above what is now the homes of 340,000 residents. In the Montreal area, the water level would go up by 4.4 metres, affecting 10,000 people.

The homes of 11.5 million people in Shanghai, 6.8 million in Hong Kong and 3.5 million in Hanoi would be under water level.

Climate-change velocity would become too high for some species to move sufficiently fast and follow their preferred temperatures.

Crop production would be at high risk with some potential for adaptation, Prof. Portner told the UN climate-change conference in Lima, last December.

Heat waves in the Middle East and North Africa for three weeks to three months.

In Mexico, more than 30-per-cent increase in dengue-fever incidence in Mexico.

+4-degrees Celsius

Sea levels could rise to submerge land currently home to 144.7 million people in China, 48 million people in Bangladesh and 46.1 million people in Vietnam, according to projections by three scientists working for Climate Central. In the United States, the homes of 24.8 million people would be under sea level. In Canada, one million people would be affected.

Median local sea level could rise by 8.4 metres in the Vancouver area, above what is now the homes of 396,000 residents. In the Montreal area, the water level would go up by 7.4 metres, affecting 54,000 people.

The homes of 22.4 million people in Shanghai, 10 million in Hong Kong and 7.6 million in Hanoi would be under water level.

Climate-change velocity would be much too high for terrestrial and freshwater species to move and relocate.

Crop production would be at high risk. Biodiversity would be lost and the catch potential of fisheries would be highly reduced, Prof. Portner says.

Heat waves in the Middle East and North Africa for two months to 200 days.

Increase in the incidence of morbidity associated with food and water-borne diseases in Beirut of 35 to 42 per cent. In North Africa and the Middle East, 39 to 62 million more people exposed to risk of malaria. Howver, there will be a decreased malaria length of transmission season for tropical Latin America.

Mitigating the effects of climate change and meeting targets will require large and sustained cuts in greenhouse gas emissions, a shift to renewable energy and trillions of dollars

Capping temperatures at 2 degrees Celsius above preindustrial levels by the end of this century will be a massive global undertaking, according to experts. Even with current emission-cut pledges made by countries in the prelude to the Paris climate talks, the planet is on track to warm by 2.7 degrees Celsius, according to the United Nations. Some scientists believe the figure is closer to 3.5 degrees.

Limiting a global rise in temperature to 1.5 degrees Celsius would mean dramatic cuts in greenhouse gas emissions, a global shift away from fossil fuels, rapid development of renewable technologies and trillions of dollars of funding to help developing nations meet targets.

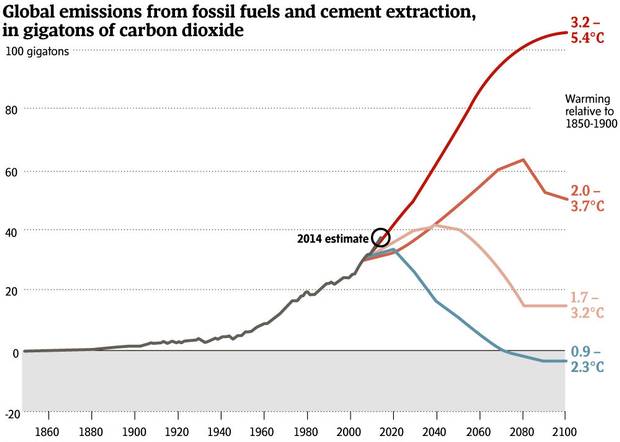

Curbing carbon emissions is key to lowering the Earth’s surface temperature, but by how much will inevitably be determined by the level of emissions cuts. The worst-case scenario sees fossil fuel emissions continuing with no change; the best-case calls for a drastic and immediate drop.

Trish McAlaster/The Globe and Mail / SOURCES: CDIAC/GCP/Friedlingstein et al 2014, via Global Carbon Project

Global emissions

Michiel Schaeffer, a physicist and climate scientist at the Berlin-based Climate Analytics policy institute, said to meet the 2-degree goal, global greenhouse-gas emissions would need to be cut to zero some time between 2080 and 2090.

In the 1.5 degrees Celsius scenario, that would need to happen earlier – some time between 2060 and 2080, explained Dr. Schaeffer.

By the middle of this century, countries would have to make significant progress in emissions cuts – between 40 and 70 per cent to reach 2 degrees and 70 to 95 per cent to reach 1.5 degrees, according to Dr. Schaeffer.

For Canada, hitting a target of 1.5 C will mean cutting emissions by a third over the next decade and achieving zero greenhouse-gas emissions over the next 30 to 35 years, according to Ian Bruce, director of science and policy at the David Suzuki Foundation.

On a global level, keeping the planet's temperature rise to less than 1.5 C by the end of this century would mean a massive weaning off coal and other fossil fuels that are putting heat-trapping gases into the atmosphere.

That will be a challenge in some rapidly developing countries such as India, the world's third largest emitter, which has plans to build more than 440 coal power plants over the next 15 years.

Dr. Schaeffer said that all existing plans to build coal plants around the world would have to be stopped – and other plants allowed to retire or converted to gas or cleaner energies when their lifespan of 50 years expires.

Renewable energy and carbon capture

Keeping the global temperature rise under 1.5 C by the end of this century will require a significant ramping up of renewable-energy technology, such as solar, wind and bioenergy technologies, as countries shift away from fossil fuels.

In Canada, achieving a zero-emissions economy will mean industry using renewable sources of energy and capturing carbon. It will also mean buildings and cars will need to become more efficient.

The David Suzuki Foundation is proposing a 100-per-cent renewable-energy goal by 2050. As an interim goal for 2030, it says Canada should consider the 50/50/50 plan, being considered by the State of California.

In that scenario, 50 per cent of a country's electricity would come from renewable sources, buildings would use 50 per cent less energy and the fuel used by cars and trucks would be cut 50 per cent.

Mr. Bruce, the foundation's director of science and policy, points to examples of progress in Canada such as the phasing out of coal from Ontario's electricity industry and British Columbia's carbon-tax plan.

"The real lesson there is that the federal government has a vital role and we can do so much more with a unified strategy on climate change," he added.

The focus right now is on the global electricity industry – the cheapest way to reduce emissions and curb global warming, explained Dr. Schaeffer.

Reducing emissions in the building and transportation sectors is much more expensive and harder to achieve – and those are the sectors countries will need to look at if they want to go from a 2 C goal to under 1.5 C, he said.

Adaptation fund

Ambitious global goals on capping temperatures would require developing countries to "leap frog" fossil fuels and it would mean developed economies providing financial assistance, explained Mr. Bruce of the David Suzuki Foundation. This would need to happen at a time when many of those developing nations are growing quickly and hoping to stay on that rapid economic growth path.

But most of these countries do not have the money or technological know-how to make a rapid transition to a clean-energy economy.

"For a 1.5° C or even 2° C degree pathway, there is consensus that the annual investments required in the energy sector alone [would] have to grow significantly up to about $1-trillion per year by 2020 and up to about $2-trillion per year by 2030/2035," stated a report called Fair Shares, endorsed by a global coalition of NGOs and civil-society groups. Most of these funds would be needed in developing countries.

Existing global climate -hange financing initiatives to help developing economies currently sits at about $15-billion, according to the report.