Para ler esta reportagem em português, clique aqui

In Guarani, they are called mokoi and gwyra. You can think of them like two small birds that fly to join you at the moment of birth and travel on your shoulder all your life. They are the guardians of your ayvu, your animating force, your soul. If you grow old, and your body wears out, then the birds depart for their natural home in the cosmos. That's a good death.

But the birds can also be frightened off your shoulder, long before your body wears out. They can be dislodged by harsh words, or by a shocking sight – your lover encircled in someone else's arms, for example. The birds may settle and return to you – but they may not. That is when trouble begins: The most evil spirits, the angue, that are around us and in us, can take over then.

The angue can lead you to do all manner of bad things. They may even give you the idea to pick up a rope, toss it over the branch of a tree, pull it tight around your own neck, and jump. Jejuvy, in Guarani: It is usually translated as suicide in English, but that's a limited word – the clear implication is that the angue suffocated you, after giving you a wish to die. And then the spirits are loose, and if no one is on hand to take steps to stop them, they can fan out to cause new suffering – including jejuvy in many others.

Once the hangings have started, it can be a very long time before they stop.

Jejuvy took hold in December, 2015, in Sassoró, an Indigenous reserve in central Brazil that is home to 3,800 people. The first to die was Junior Silveira, who was 20. He hanged himself from a large tree in a clearing between the houses. His family found him near dusk, and the chief, Paulo Fiel, called the police – but they are never quick to answer calls from the reserve, and it wasn't until the next day that Mr. Fiel was given permission to cut his body down.

"By then, everyone had seen, even the little ones," said Junior's mother, Maria Benites. Years ago, a child would never have been permitted to see a victim of jejuvy. These days, you can hardly prevent it.

After Junior, the deaths came swiftly, a 15-year-old boy, a 14-year-old girl. Until the last to die: Junior's brother, Gilmar, who strangled himself with a belt on a post inside the family's rough board house in October.

"They were not sad boys – they were normal," Ms. Benites told me, her voice flat. "They liked school. They played football. They went to dances. They were always together.

"Something happened to them."

Maria Benites looks at a photo of one of the two sons she lost to suicide over the past 15 months at her home on the reserve in Sassoró.

Parallels to a Canadian crisis

There is a suicide crisis among Brazil's Indigenous people, who take their own lives at an average rate 22 times that of non-Indigenous Brazilians. Among the non-Indigenous Brazilian population, it is men over 60 who are most likely to kill themselves (a statistic that is in line with most Western countries); on Brazilian reserves, it is almost entirely adolescents who take their own lives. More boys kill themselves than girls, but the rate of suicide by girls is growing more quickly. The overall Indigenous suicide rate is higher than the national one across the country, but it is wildly higher in a handful of places.

The situation has many parallels with the phenomenon of Indigenous suicide in Canada, with one conspicuous difference: In Canada, it is called a "crisis." Prime Minister Justin Trudeau has pledged urgent action on Indigenous suicide, and cabinet ministers have promised a federal intervention (although Indigenous leaders say both a plan and resources are still starkly lacking).

In Brazil, however, there is no talk of a crisis. In 2015 the federal government announced a prevention plan for what it calls the worst-affected reserves (pledging to cut suicide by 10 per cent) but it will not make public the budget or where that plan is supposedly being implemented. This belated and haphazard response reflects, in part, the fact that the country is mired in economic and political turmoil that has pulled away resources and attention from most social problems. But even at the best of times, Brazil's 900,000 Indigenous people are profoundly marginalized, the poorest citizens, little remembered, less served.

No more than a dozen people in Brazil, a country of 210 million, are researching the possible causes of the astronomical rates of Indigenous suicide. Community-level resources are pitifully scarce: For the 70,000 Indigenous people in the state of Mato Grosso do Sul, where Sassoró is located, there are 13 psychologists, none with more than an undergraduate degree.

It is difficult to determine precisely when this problem began, because data are predictably scarce: A federal Indigenous health service has kept statistics only since the mid-1990s. But suicides – occurring in such large numbers, not just one or two in a generation – are by all accounts a recent phenomenon. Most people the age of Ms. Benites, who is 52, say it never happened when she was young. The phenomenon first drew attention in Brazil with a spate of suicides among her people, the Guarani-Kaiowa, in 1986, when the Brazilian Indigenous affairs agency noticed a spike – from about five a year to 40. Statistics collected since 1996 show an average of 46 a year – a rate that is 21 times greater than the national one. Many of those who work in the field say this is probably a sharp underestimation, since Indigenous deaths are almost never subjected to a coroner's analysis, and are often simply not recorded at all.

São Gabriel

da Cachoeira

Suicide hot spots

Boa Vista

State of

Roraima

Tabatinga

State of

Amazonas

BRAZIL

State of

Mato Grosso

Do Sul

BOLIVIA

Dourados

Amambai

Sassoró

TRADITIONAL

GUARANI-

KAIOWA

TERRITORY

ARGENTINA

URUGUAY

THE GLOBE AND MAIL, SOURCE: INDIGENOUS PEOPLES

RIGHTS (CTI) AND INSTITUTO SOCIOAMBIENTAL (ISA)

Suicide hot spots

Boa Vista

São Gabriel

da Cachoeira

State of

Roraima

Tabatinga

State of

Amazonas

BRAZIL

State of

Mato Grosso

Do Sul

PERU

BOLIVIA

Dourados

Amambai

Sassoró

TRADITIONAL

GUARANI-

KAIOWA

TERRITORY

ARGENTINA

URUGUAY

THE GLOBE AND MAIL, SOURCE: INDIGENOUS PEOPLES RIGHTS (CTI)

AND INSTITUTO SOCIOAMBIENTAL (ISA)

Suicide hot spots

Boa Vista

São Gabriel

da Cachoeira

State of

Roraima

Tabatinga

State of

Amazonas

BRAZIL

State of

Mato Grosso

Do Sul

PERU

BOLIVIA

Dourados

Amambai

Sassoró

TRADITIONAL

GUARANI-

KAIOWA

TERRITORY

ARGENTINA

URUGUAY

THE GLOBE AND MAIL, SOURCE: INDIGENOUS PEOPLES RIGHTS (CTI) AND INSTITUTO SOCIOAMBIENTAL (ISA)

Among the suspects: chronic disease, drug abuse

As a series of suicides by young girls in Northern Saskatchewan made news in Canada in recent months, I went to Sassoró, and to reserves scattered through Guarani-Kaiowa territory, to try to understand what is happening here, and what, if anything, is being done in response. I talked to the psychologist whose catchment area includes the Benites family; to the regional health authority; to traditional healers and to anthropologists; to parents and siblings of the dead.

When I asked people why they thought the young Guarani-Kaiowa are killing themselves, they told me about lost land and lost rituals, and the lure of the city and fancy sneakers and cellphones. About chronic disease and near-universal unemployment. About alcohol and drug abuse, and a generation of children whose parents feel they cannot control them. (And a generation of children who feel their parents should not try to control them.) I heard about the nature of the Kaiowa, some of whom described their people to me as closed, reserved, disinclined to share emotion but prone to sticking fiercely to an idea once it has entered their minds.

And I heard about the mokoi and gwyra, the birds of protection that can be startled away. That explanation, in the end, made as much sense as any of the others.

Brazil has 900,000 Indigenous people, and 480 "demarcated territories" encompassing just over a million square kilometres, 12 per cent of the country's land – land set aside for Indigenous people to live on. (Indians, as they are almost universally known here, have no ownership rights, or control of minerals or anything else beneath the soil.) Some 400,000 of those indigenous people live away from those demarcated territories, in rural areas or in cities.

The Indigenous people of the Amazon rain forest, with their bowl haircuts and yellow feather headdresses that are a National Geographic staple, are the archetypical Brazilian Indian. And 98 per cent of the demarcated Indigenous land is in the Amazon. But the second-largest Indigenous population in the country is here in Mato Grosso do Sul, a state on the western flank of Brazil that shares a border with Paraguay and Bolivia. There are eight First Nations in the state – "ethnicities," they are called in Brazil; the largest, by far, is the Guarani-Kaiowa, who make up two-thirds of the Indigenous population and whose traditional territory is today fractured between the three countries.

On the Brazilian side of the border, the Guarani-Kaiowa have nine reserves in the south of Mato Grosso do Sul. This is breadbasket territory, the heart of Brazil's thriving industrial agriculture business. The land is a vast sea of green fields of soy, spiky sugar cane, and darker green corn, owned by a handful of giant firms, many of them multinationals. While the rest of Brazil staggers under the weight of a stalled economy, plenty of money is still being made here: The Asian market's hunger for Brazilian soy, and for beef fed on soy, has not dimmed. Once in a long while the farmland is interrupted by a town, built around a plaza, with a handful of clothing stores and gift shops, a couple of bakeries, and lines of big trucks idling at the one traffic light.

You can drive for 15 or 20 minutes at a stretch and pass only fields that are pasture for white Brahman cows. After a while, you realize that far more land here has been given to cows than to Indigenous humans.

The reserves are unmarked; you have to know what you are looking for to find them, down long, rutted, red dirt roads. Eventually there are houses in among the scrubby bush – the best ones a couple of low rooms with plaster over mud brick; the poorest, such as that of Ms. Benites, just tarp pulled over sticks. Each reserve has a school, where all classes except Guarani language are taught in Portuguese. The schools are chronically short of teachers and the most basic quality control. Just 5,400 Indigenous people in the state have made it as far as the first year of high school. There is usually a small health post on each reserve, where for a few hours each day an "Indigenous health agent" vaccinates babies and doles out tuberculosis medication.

There are plenty of trees between the houses, and a sense of spaciousness; there is also a total absence of any kind of economic activity. The teacher and the health agent are the only people on most reserves with paid employment. The only jobs to be had are day labour on the farms, a few months a year during harvest – but farmers don't like to hire " Índios." Sometimes women get jobs washing clothes or floors for white people in the town – but it's far, and the work pays only about $20 a day.

Brazil's Indigenous people had their first interactions with European colonizers in 1500, along the Atlantic Coast. So, some of them have more than 500 years' experience dealing with the mundo branco, the white world. But colonialism came much later to the deep interior of the country. The first plantation land grants in Mato Grosso ("thick forest" in Portuguese) were doled out to white settlers in the 1800s, but a major effort to control the movements of the Indigenous people began only in 1915.

For decades, most of the Guarani-Kaiowa managed to stay away from the reserves, and kept to the forests. But by the 1970s, the last swaths of forest were being cut down for cattle ranches and maté plantations, and the government drove the Guarani-Kaiowa off their land and into small reserves. The pain of the displacement was then compounded: Before they were moved, the Indigenous occupants were forced to act as slave labour, clearing the land for the new farms, and building the roads that would serve them; some were obliged to continue for generations as unpaid farm workers.

The relocation was, by all accounts, a catastrophe for the Guarani-Kaiowa. They were a semi-nomadic people used to ranging over large distances, suddenly denied access to their traditional means of supporting themselves. The forests were razed, the wild animals they hunted disappeared, and the water sources were drained to irrigate plantations. The relocations upended the Guarani-Kaiowa in another, terrible way: Particular places are essential for the practice of their rituals for planting, for hunting, for marriages and treating illness. A family's tekoha, its original and sacred land, is the source of teko pora – words that mean, essentially, to be alive and well. When they were "interned" – that is the word people usually use to describe the dislocation – everything began to fall apart.

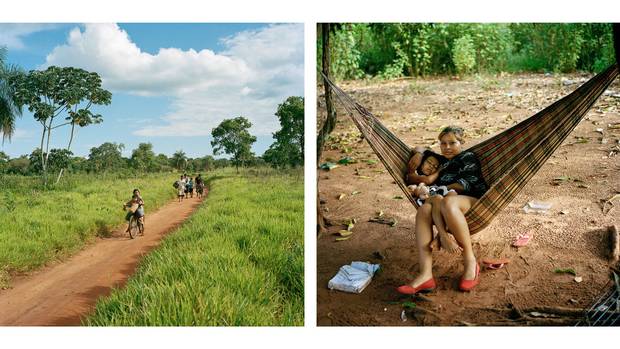

Left: Youth in the village of Limão Verde on the Amambai Indigenous reserve pay desultory attention to a cultural presentation intended to build self-esteem.

Right: Amambai rsidents attend a community meeting organized by SESAI, Brazil’s Indigenous Health Agency. The agency has launched a new initiative to engage community elders and service providers such as police officers and pastors in efforts to lower the rate at which Guarani-Kaiowa people, particularly teens, take their own lives.

'Lots of things now are out of control'

"The deaths, the murders, the suicides – they have to do with how we live now," Izaaque João, who lectures on Guarani-Kaiowa religion in a local college program for Indigenous teachers, explained to me. "When people are mentally and physically well, it's fine, but when we're not, the spirit can get to us, because we're not protected. A way exists to protect the group, but what happens now is that shamans are not doing the rituals to protect the people – they have inadequate space to do it. To do it you need your proper place. It's a sacred thing that can't be sung anywhere."

We were sitting in front of his mud-brick house on a reserve on the outskirts of Dourados, a city of 215,000 people that is the largest in the region. Mr. João gestured briefly with his chin, taking in the jumble of houses down the road and the highway behind us that the government had recently carved through the centre of the reserve.

"This is not a sacred place – it's not purified. You can't do those rituals here."

A few days after I met Mr. João, I went to see a shaman. I drove four hours along that highway, past soy fields that stretched to the horizon, to the Guarani-Kaiowa reserve at Amambai. It's a languidly bustling, cheerful community, with a well-built school and playing fields for kids. The town of Amambai is about 20 minutes up the road, so a few people go there for work. But the darker side of life here is also apparent: In the middle of the day, you come across women so high on something they can barely walk, leading a pack of filthy half-dressed children down the centre of the road. Amambai has been notorious in recent years as the community with the highest suicide rate in Brazil, a grim title it lost this year to Sassoró.

Early in the morning, I found Ilma Gomes, 58, at home, cooking something in a huge, soot-stained pot over a wood fire in a lean-to. Dried gourds doubled as dishes, animal skulls were stashed in the rafters, and mysterious leather bags of things hung on the stick walls; she was playing Guarani ritual music off a thumb drive in a laptop. She wore capri pants and a chiffon shirt; her silver hair was pulled back in an elegant knot.

Ilma Gomes is a Guarani-Kaiowa shaman who lives on the reserve in Amambai. After 17 people, mostly teenagers, took their own lives in the community in 2015, she and other traditional healers got together to perform rituals to strengthen the spiritual forces they said could protect the children.

She echoed what Mr. João had told me: Few people do the rituals any more. There are many rituals a Kaiowa must do each day, like taking herbal remedies, to keep the angue away. There are the steps a parent can take if they fear their child is menaced. There is a protective leaf they must use to wash their hair. Prayers they must say, to keep safe. But they don't.

"Lots of things now are out of control," she said, popping up and down from the bench where we sat, to stir the smoking pot. She described how all the youth on the reserve walk around with headphones on, looking at cellphones. "There is a voice speaking right into their heads and they don't control what goes in their heads – this takes children into despair, it amplifies sadness," she said, in Guarani. "They fall in love secretly and sometimes start drinking – without the control of the rituals they should be doing."

Sometimes mothers come and ask for her help with their children, Ms. Gomes told me. "When the parent sees they are not well, it is the moment to intervene," she said. "If no one notices, it's a problem."

Often, these days, she said, parents are not watching.

Left: A pickup soccer game on the reserve in Amambai. This reserve has over the past 20 years had one of the highest suicide rates in the world.

Right: Nelza Gonçalves attends the suicide prevention meeting in Amambai organized by SESAI. The agency will not make public where it is targeting or what the program budget is.

Left: A family walks a path in Amambai in southwestern Brazil.

Right: Ellen Rodrigues Sarmori holds her sleeping sister Wendy on the reserve in Amambai. Their brother Allen, 16, was found hanging in a tree a year ago. Neighbours say he was frustrated his parents could not afford to buy him nice sneakers or a fancy cellphone. His mother believes jealous forces, human or otherwise, took his life.

High rates of violence, and communities disrupted

A few days before I met Ms. Gomes, on my way to Guarani-Kaiowa land, I went through the state capital, Campo Grande, and stopped in at the pristine blond-wood office of the state's Indigenous health service. There, I heard some of the data that lies behind the kind of fractured families Ms. Gomes would tell me about. I met with Edemilson Canale, who is in charge of the service, and Fabiane Vick, a psychologist who heads up the mental-health initiative.

Mr. Canale, a public-health expert, is Terena, one of the First Nations native to the region, while Ms. Vick is white, and did her master's thesis on Guarani-Kaiowa suicide. They talked about the high rates of violence in Guarani-Kaiowa reserves, of endemic domestic abuse, child sexual abuse, and incidents of assault; and about alcohol and drug abuse, which they said was widespread, even among children. Mr. Canale said that his chief preoccupation is child mortality – the Indigenous rate in the state is more than double the figure for Brazil as a whole – and both of them talked about how difficult it is to try to tackle issues related to mental health when many of the people they try to serve are malnourished and living in decrepit homes, problems outside their ostensible mandate.

In addition to the internal violence, there is external conflict, Mr. Canale explained: Since the 1980s, groups of Guarani-Kaiowa have been attempting to reclaim land they say is theirs, pitting them against agribusiness. The violence has intensified as the farms have expanded. Two chiefs were murdered in the past six years, and there were shootings, kidnappings and disappearances, leading to a constant sense of menace around Indigenous communities.

Mr. João told me about this, too: Attackers are rarely charged with assaults on Índios, he said, because the state and federal congress representatives are closely tied to agribusiness. State and federal military police often carry out evictions of Guarani-Kaiowa squatting on land they seek to reclaim; farmers use guards (with military-grade weaponry) from private security firms staffed mainly by ex-police.

Evangelical churches have had a strong and constantly expanding presence on Indigenous reserves in the past 15 years, and, Mr. Canale said, forcefully discourage their followers from consulting traditional leaders or healers. The result has been disruption of communities and families. Izaaque João, the teacher of Guarani-Kaiowa spirituality, talked about that, too.

Guarani-Kaiowa youth grow up with access only to poor education, with no recreational option beyond drinking – which they often start to do before they are 10 – or smoking the abundant marijuana that comes over the border from Paraguay, or crack, the health workers said; they have virtually no career prospects, and yet plenty of exposure to another, parallel life that they see on TV, and in the towns. Ms. Vick said that in interviews with families of teens who have killed themselves, parents say their children "see everything, the televisions, the cellphones, the nice clothes, they see it and they want it but they live in another world."

Studies of Indigenous youth in other countries have demonstrated the corrosive effect of "increasing relative disadvantage." Although Brazil is currently facing a crisis of unemployment and inflation, real standards of living for most people here improved dramatically in the past 15 years. The poorest Brazilians – with the exception of Indigenous people – benefited most; fully 35 million moved out of poverty altogether. Almost none of that change reached the reserves.

I visited 10 families on reserves in southern Mato Grosso do Sul who lost at least one member to suicide in the preceding year, and the stories the grieving parents told me had many common elements: He fought with his girlfriend. He was angry because I said he could not live with the girl he liked. My daughter was drinking. My son wanted new runners, and I said I could not buy them. "They're banal things," Paulo Fiel, the elected leader in Sassoró, told me. But the conflict could be enough to startle off the mokoi and gwyra, he said, and leave a soul vulnerable.

Ms. Vick, the head of the mental-health team, said their epidemiological tracking shows that suicide comes in waves, something they are at a loss to explain. Mr. Izaaque, however, said it makes perfect sense: With no rituals to control the spirits that break loose in jejuvy, and no rituals of protection, the evil spirits wreak havoc on one person, and then the next.

In photos: Guarani-Kaiowa country up close

Cattle ranching and industrial soy farming have taken over most of the land that was once Guarani-Kaiowa territory. Indigenous people have many land claims in the area registered with the federal government, but these take decades to be adjudicated.

Residents of the Guarani-Kaiowa reserve at Amambai blocked a nearby highway in November to protest the fact that half the community had been without running water for nearly two months after a pump broke down. Protest leaders said that only blocking the highway brings attention from the Indigenous affairs organization that manages utilities and other services for the reserve. Police separated the protesters from angry white farmers wanting to use the road to get to town.

Children play in a schoolyard in Amambai. Guarani-Kaiowa youth grow up with access only to poor education.

Araci Samor of Amambai lost her husband Nivaldo Chara Martin, 42, and son Michel, 15, to suicide.

A soy field next to the village of Jiguarapiru. Traditional Guarani-Kwaiowa land is today the heart of Brazil’s agro-industry, a booming sector in an otherwise moribund economy. The highly mechanized farms employ few workers, and people on the reserve say white bosses don’t like to hire ‘ Indios.’

.

Suicide 'hot spots,' but few clear-cut explanations

The theory that roots the clusters of death by suicide among the Guarani-Kaiowa in the loss of their land is compelling, and it is cited in virtually all the research or public discussion about the issue. But it raises serious questions. First, why is it only the Guarani-Kaiowa? There are seven other Indigenous ethnicities in Mato Grosso do Sul, all with similar trajectories of dispossession, yet only this one has a suicide crisis.

Eighty per cent of Indigenous suicides take place in four "hot spots," which are home to 40 per cent of the Indigenous population. The first is Mato Grosso do Sul; the other three are in the Amazon rain forest, among ethnicities that have dramatically different experiences from the Guarani-Kaiowa – they have not been driven off their land, they continue to practise traditional agriculture and hunting and handicrafts, and in many cases they are the dominant ethnicity in their towns. Two of the Amazonian communities share some features: They are in remote areas near borders with Colombia and Peru – where the federal government has made a push in recent years to increase urbanization and establish a Brazilian (that is, non-Indigenous) presence. There is a large military installation in each, and a growing influence of drug traffickers. But the fourth of the "suicide hot spots" is in a state to the north, in its largest city, with nothing in common with the other areas.

"The question of demarcation of land is an interesting lens to look at the suicides in Mato Grosso do Sul," said Maximiliano Ponte de Souza, a psychiatrist based in the Amazonian city of Manaus who is one of the leading (and, he points out dryly, one of the only) medical experts on Indigenous suicide. "But that doesn't apply to the Amazon, which is where the largest Indigenous territories in Brazil have been demarcated."

Most of the rain-forest communities share one feature: Starting in the 1950s, children about nine or 10 years old were taken from their families to live in a network of religious boarding schools run by Salesian Catholic priests, in an initiative enthusiastically endorsed by the federal government. The schools had a rigorous schedule that combined studying in Portuguese (Indigenous languages were forbidden) and manual work on farms. There have not been reports in Brazil of widespread sexual abuse in the schools, but then there has been no public accounting of the residential-school experience. Dr. Ponte de Souza says children were taken young – because that was viewed as the best way to break the cycle of passing on their community's spiritual beliefs – and in the process, missed the rituals for the process of becoming adults. The last of the schools was closed in 1986.

The loss of rituals features in a number of anthropology journals, but this is not a clear-cut explanation either: Each of the three Amazonian hot spots is home to a number of ethnic groups, but as with the Guarani-Kaiowa, only one such group, in each place, has a suicide crisis. In this, the Brazilian situation mirrors Canada's: There are Canadian Indigenous communities with epidemics of suicide, such as Northern Saskatchewan; and Attawapiskat in Northern Ontario, where more than 100 people tried to kill themselves in the past year. But there are also Indigenous Canadian communities where the suicide rate is lower than the national one. In a single geographic region, different First Nations have a marked difference in suicide rates – the James Bay and Northern Quebec land claim, for example, covers both Cree and Inuit; only the Inuit have elevated rates of suicide. Suicide in Canada is often connected with the residential-school experience, yet the largely Catholic communities that surround the former residential school at Chesterfield Inlet in Nunavut have some of the lowest suicide rates in the territory.

In Canada, there is research under way to try to understand why suicide occurs within some but not other groups with highly similar socioeconomic environments and experiences of colonialism. In Brazil, Dr. Ponte de Souza works out of a closet-sized office stuffed with what passes for an archive and struggles to scrape together funds to allow a graduate student or two to do field work based on interviews with a dozen people.

In Mato Grosso do Sul, I asked everyone I met why they thought the Guarani-Kaiowa are plagued by suicide, when other First Nations living on the surrounding land are not. Edemilson Canale, the head of Indigenous health services, said the Guarani-Kaiowa reserves are closest to the cities – giving people a sense of what they lack – but also located in the part of the state with the fewest employment possibilities. As a people, they were traditionally semi-nomadic, whereas the people of the Terena ethnicity, for example, always farmed, making the "internment" harder for the Guarani-Kaiowa.

His colleague, the psychologist Fabiane Vick, said her staff reports that the Guarani-Kaiowa are "much more introspective and reserved than other ethnicities … our professionals find it very difficult – they don't share their emotions or suffering. It's locked away, even with their own people."

But Dr. Ponte de Souza said this line of explanation makes him uneasy. "People seek answers in the sociocultural organization of each group and their differences. 'The Terena are more open in incorporating the new, unlike the Guarani-Kaiowa' – that kind of thing. This … places the blame for the suicide on the victim," he said. "I ask, 'Is suicide perhaps a social strategy for diminishing suffering?' If I say 'Their culture is the cause,' I forget all the suffering that the community endured."

In every conversation about suicide he has ever had with Indigenous people of every ethnicity, he said, it is clear that they see it as a "bad death," not desirable – so it is difficult to believe there is anything inherent in the people or their culture that makes suicide an acceptable choice, he added.

No warning signs – and no one looking to help

In Sassoró, I found Maria Benites sitting in a broken bamboo chair in the dirt patch between the two lean-tos where she and her grandchildren have been sleeping. They moved here from another house after Gilmar killed himself in October – most families choose not to stay in a house where jejuvy has happened. She got up and brought out a small, rickety bench for me to sit on – the best piece of furniture for a visitor. The combined material possessions of Ms. Benites and the two children and four grandchildren who live with her would fit in a laundry basket.

Nilcilene, 10, and Vera Lucia, 5, listen while their grandmother Maria Benites talks about two of her sons, who died by suicide in the past year and a half.

She said there was no warning sign that either of her boys was considering suicide. Junior, she said, was angry that she didn't want him to go to an all-night dance party with a friend she believed was a drug user. And when Gilmar died, 10 months later – he missed his brother, and he was squabbling with his pregnant wife. But she believes someone may have been envious of her good-looking, healthy sons, and put a spell on them. That, she believes, could unlock angue as well.

And that makes her fear for the grandchildren. "I think every day they might take the same path," she said. "I need to find out who cast the spell, so they can't do the same to the others."

But the loss of both these boys, in just a year, has left Ms. Benites bone-achingly weary, with a sparseness to her movements and an even greater economy of words. Thoughts of those boys catch her mind and draw her away for long stretches, when she sits and stares into the middle distance.

One thing Ms. Benites did not tell me, something I learned later from the reserve leader, Paulo Fiel: Junior Benites had tried twice before to kill himself. No one in the family sought help, at the time, or later. None came to them.

Dr. Ponte de Souza told me he hears variations of this in many of the verbal autopsies he does with the families of suicide victims in the Amazon. "In addition to saying that the people were 'normal' and 'fine,' family members also said that the person who died by suicide had already attempted suicide other times," he said.

"In other societies, this situation would be considered very alarming and not at all 'normal.'" But the terrible frequency of suicide has served to normalize it. "And although people have attempted suicide various times, they haven't sought help, either from the Indigenous health agents or from traditional sources."

And although the deaths were recorded as suicide, help has not sought them, either. On the reserve in Amambai, I met Claudinéia Rodrigues and Fernando Sarmori, who agreed to talk to me about their son, Allen. We settled together in the yard, as their daughters – a six-year-old with a grimy Barbie; an aloof 16-year-old – swung in a hammock in the yard.

Allen was 16, in his first year of high school and thinking about a career in the military when he was found hanged in a tree near their home a year ago. Ms. Rodrigues sobbed and rocked from side to side, tipping forward so that her dark hair tumbled over to hide her face, saying she was sure someone had a hand in her son's death, then telling me that he had her cellphone and was wearing a new shirt she had bought him, on the day he died – words that sounded almost defensive, because the neighbours had told me Allen was angry at his parents that he couldn't buy a phone or new clothes. "Why did they take the life of my son?" she asked, and wept, and the "they" seemed as if it encompassed all who wished her ill, human and otherwise.

Mr. Sarmori, a tall, thin man, stood behind his wife raking distractedly at the dirt, and told me Allen wasn't the first, far from it: His father and his sister both hanged themselves. So did Ms. Rodrigues's brother.

And yet, despite this, Allen's parents said that I was the first person to come to their home to ask about him and what was happening when he died. The first to ask about any of the suicides in the family. No mental-health professional has come, no one from the medical service or the reserve leadership, Ms. Rodrigues said. I heard this in every one of the homes I visited: No one has come. No one has asked.

A jarring encounter

The psychologist who covers this region is an earnest white woman named Monay Larissa de Souza, who is 29. For six years, she served the community – whose language she does not speak – alone, even as the number of youth suicides rose steadily. Last year, two more psychologists were added to her team. Now they are attempting to visit every home where someone takes his or her own life, in order to identify and try to track family members, she said – because they have learned that when there is one, there will usually be more.

In Sassoró, the psychologist assigned to the area is one of the few Indigenous professionals in the health service, a Guarani-Kaiowa woman named Barbara Rodrigues. (She doesn't speak the language either, because her mother, determined that she would get a good education, put her in a "white" school where she learned Portuguese.) She has been in the job a year, and says if she had known what it would entail, she might not have taken it. She hears stories of abuse, but says she has no way to intervene; stories of people in the community selling alcohol to minors, but can do nothing about it. "It's a very frustrating job, I won't deny it," she said, in a late-night conversation on the porch of her home in Tacuru, the town near the reserve. "I identify risks and tell the rest of the services, and nothing happens. I'm here to collect statistics – there's nothing else I can do."

In her lap, she held a pink, glitter-spackled folder of her case notes: interviews with family members and friends of the young people who killed themselves in Sassoró this year. Each one was a litany of misery – of alcoholism, domestic abuse, unemployment, hunger for opportunities that didn't come. But the reasons family members give for suicides – "they're just trivial things." It leaves her mystified. "If I could say that's the thing that's causing it – fantastic, we'll go there and tackle it. But I can't say."

Ms. Rodrigues's concern was palpable, but I did not find it echoed everywhere. On the reserve in Dourados, I had a jarring encounter with the mental-health services. I drove up to the administration office and met the community leader. When I told him I was reporting on suicide, he replied, "We had one yesterday! Or maybe it was two days ago." He summoned the psychologist on staff, Elizeti Moreira, and told her why I'd come. Ms. Moreira is Terena, the only other Indigenous psychologist working in the region. She reached into her pocket and drew out her mobile phone, thrusting it toward me to display a picture. "He had been in to see me just two days before, and when I heard the news, I rushed right there to see if it was the same guy. And it was! Hanging here." She laughed in apparent amazement and shook her head. In the photo on her screen, a man in blue shorts hung from a mango tree, his neck crooked sharply to the left.

Psychologist Elizeti Moreira looks out the window of the health centre on the Dourados reserve.

She led me to her office and read me her case notes from her meeting with Onildo de Oliveira. He was a father of four, unemployed and deeply troubled about his inability to find work. His former wife had had him detained for failure to pay child support once before, and he didn't want to return to jail. The children asked him for food, and he had nothing to give them. He went to apply whenever he heard about jobs, but the people hiring made clear those jobs weren't for Índios.

Ms. Moreira put his file down and repeated that she had had no hint he might be suicidal. I asked her what she would have done had she suspected he might be. She told me how, a year earlier, a woman of about the same age had come to see her, similarly desperate about how to feed her family. Ms. Moreira had got her a job washing clothes with a white friend in town, "and then she was fine." But with Mr. Oliveira? "Because he's a man, there's nothing I could do."

I asked if I might be able to meet his family, and the leader told a reluctant Ms. Moreira to show me the way. As we drove up, through a thicket of trees, she pointed out the one where he had killed himself. His mother, Celestina Vilhalva, 58, tiny, hunched, with a weathered face, was crocheting on a bench outside the two-room house, but began to sob when we said we had come to ask about Mr. Oliveira; his former wife, Mara de Souza, 33, had a dazed expression on her face. They told me that he was a good man, who went to church, and didn't drink, and they had had no warning.

Ms. Moreira, the psychologist, interrupted to bring up the cycle of suicides that could be set off now.

Ms. de Souza shuddered. "I don't know what this means for my daughter," she said.

While we talked, five-year-old Lara ran back and forth in the yard, chasing geese into the tall grass, slowing a little, from time to time, to see if her mother and grandmother still wept.

Left: Alisson Ortis and Nicole Samoiri Martin, both eight years old, play in a tree in their yard in Amambai. Nicole lost her father and brother to suicide. Right: The da Silva siblings Miguel, 4, Bruna, 6, and Neto, 8, in the village of Jaguapiru on the reserve in Dourados. Child mortality in their community is more than double Brazil’s national rate.

'Valuing life,' identifying risk

Discussion about the causes of Indigenous suicide in Canada often focus on the loss of language and cultural identity, and on how young people feel a lack of opportunities for their future. There is broad consensus that these are factors, although they raise the same questions – why some communities with these problems have high rates of suicide and others do not. Inuit communities have the highest suicide rates in Canada, but in most cases they have the highest levels, among all Indigenous peoples, of geographical, language and cultural continuity.

Some of the newer research in Canada looks at intergenerational trauma – at the impact on the young people whose parents and grandparents were coerced into relocation, or abused at residential schools, for example. There is a focus on adversity in early childhood, and how it can play into suicide risk: There is strong evidence to suggest that children who are exposed to "adverse environments" – to alcoholism and drug use, to domestic violence, to sexual abuse even if they are not its direct victim – will develop impulse-control problems and have trouble understanding the consequences of their actions. It's a description that fits every one of the cases in Barbara Rodrigues's pink folder. But none of the mental-health workers in Mato Grosso do Sul had ever heard about this research.

At the end of 2015, with 17 suicides in Amambai, Fabiane Vick and her team began to implement the government's new suicide-prevention program there. It was the first organized effort in the Indigenous health service to address suicide, even though it was the leading cause of death for people under 30.

They got better vehicles, so they could travel to more parts of the reserves, and added to the staff. "We did activities on 'valuing life' – talking about plans, dreams, goals, self-esteem – with the help of Indigenous health agents in communities," Ms. Vick said. They held meetings for pastors, leaders, and others in the community called upon to interact with the reserve, such as police and paramedics – and talked to them about identifying suicide risk, and prevention strategies. Last year, there were just four suicides in Amambai.

Ms. Vick and her team are understandably delighted. But the federal government did not make any provision for research to evaluate the impact of the intervention, or to compare the outcome to communities that do not receive it, so they have to base their plans on their faith that it is working. There was one suicide in Amambai in January, of a 26-year-old; there were none in February.

Meanwhile, when I was in Amambai, I learned that there was another suicide intervention under way, another possible explanation for the decline in deaths. Ilma Gomes, the shaman, told me that last year, after so many children took their own lives, she and the other traditional healers got together and decided they needed to take action. Clearly these children lacked the forces that would shelter the mokoi and the gwyra, would keep them in place as the guardians against evil spirits.

So the healers began to do the rituals of protection, all of them together, at once, every day – in the schools and all the places where young people gather.

"We did it for three months. And then the dying stopped."

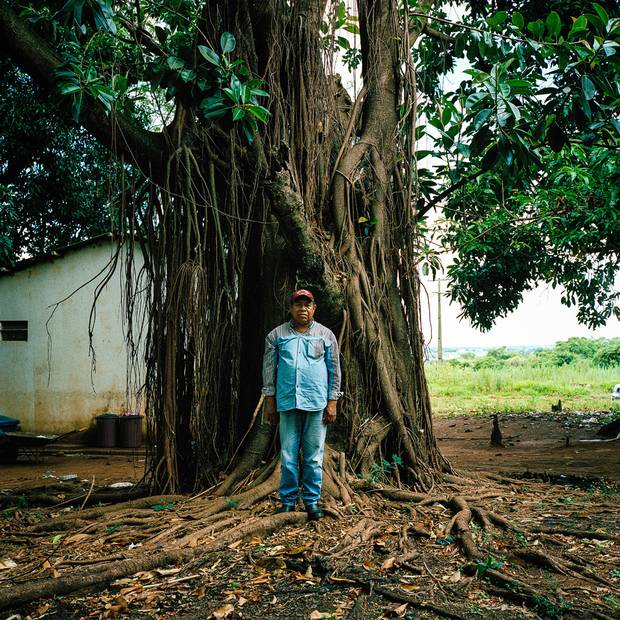

Arsenio Vasques, 63, raised his grandson Enildo from the time he was a baby. Enildo hanged himself last year, at 16. Mr. Vasques has been trying to address the rash of youth suicides in Amambai, where he is a community leader – but said he never expected the menace they call jejuvy would touch his own family. ‘To fight these suicides, it can’t just be the leaders, it has to be all of us together, teachers, pastors, we all have to be united.’

Stephanie Nolen is The Globe and Mail's Latin America correspondent. Follow her on Twitter: @snolen

With research from Elisângela Mendonça

MORE FROM THE GLOBE AND MAIL

’My cry for help could have been lethal’: An MLA’s message for Indigenous youth in distress