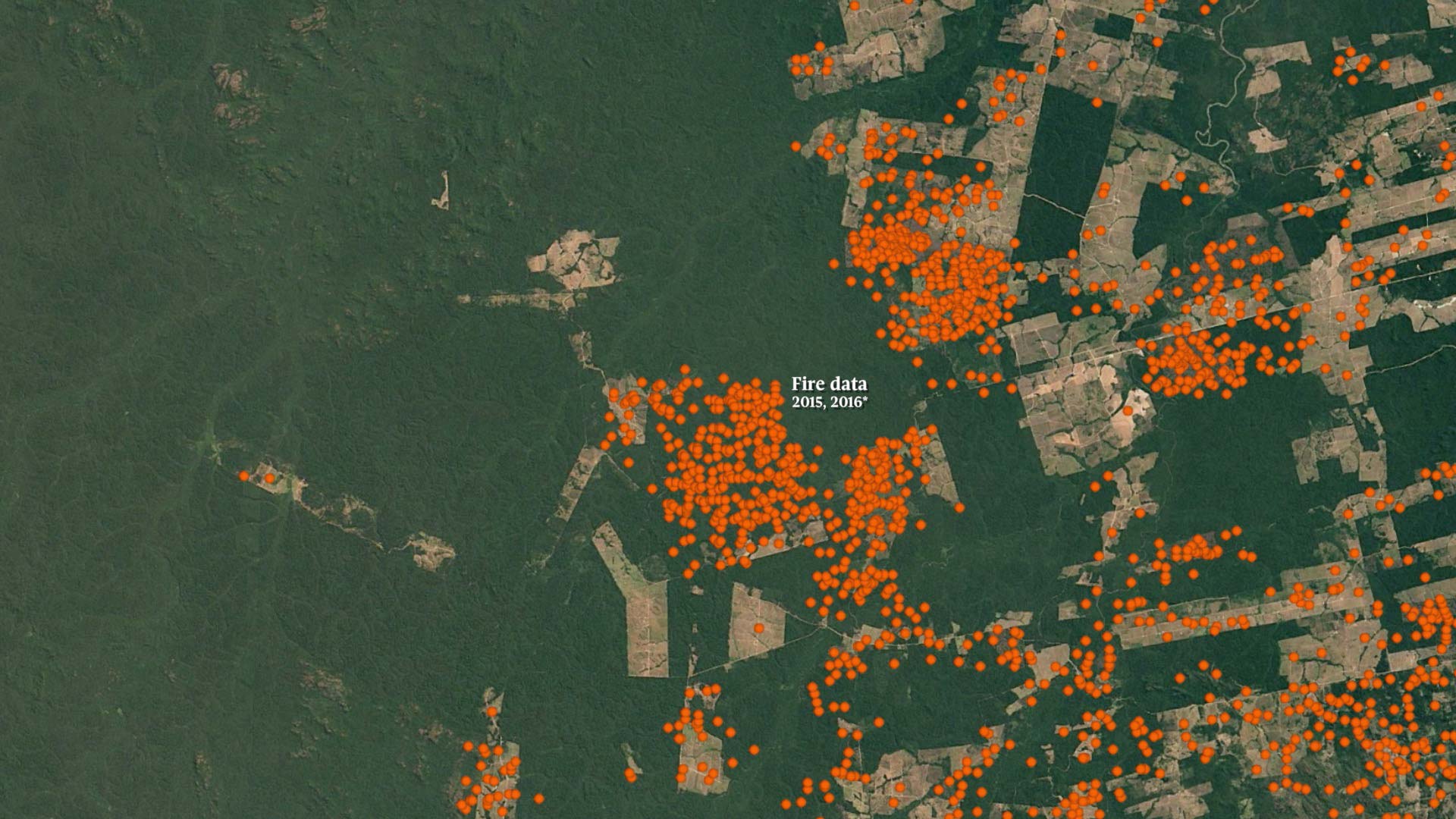

Brazil began to collect these images (on satellites belonging to NASA, China and India) in 2004, a key part of the country’s big push to stop the burning and the gouging. The pictures are sent to teams of field agents who head to the sites of fires and patches of newly denuded land, to make arrests, levy fines and destroy the equipment of loggers and miners and those who cleared the land for ranches and farms.

And it worked. Between 2004 and 2014, Brazil drove deforestation down by 82 per cent.

The early pictures photographed the forest at a resolution that showed the land in 25-hectare blocks. And so those who cleared it started to strip out smaller patches, hoping to elude the satellites. Over time, Brazil’s Ministry of Environment and the Brazilian space agency developed a new camera that zoomed in to capture images as precise as a single hectare. Deforestation rates fell further.

Yet the forest was still disappearing: A chunk bigger than Prince Edward Island vanished last year alone. And when I set out to try to understand why – and what that means, not just for Brazil, but for the rest of us humans – the most knowledgeable people I talked with seemed to be filled with a level of despair I had never encountered before when reporting on climate issues.

The story of this road, the BR-163, is in many ways the story of Brazil’s relationship with the rainforest.

When construction of the highway began back in 1972, the country was ruled by a dictatorship that viewed the Amazon as a risk: all that unoccupied territory, ripe for the taking by an enemy. And so the military rulers devised a policy, ocupar para não entregar – occupy so we don’t lose it – that aimed to move more people into the forest, fast. In the process of marking Brazilian ownership of the Amazon, the military rulers were also able to achieve another critical goal: the resettlement of poor, landless people who were then swelling the cities of Rio de Janeiro and São Paulo searching for work. This road, the BR-163, was a key north-south pole in that expansion.

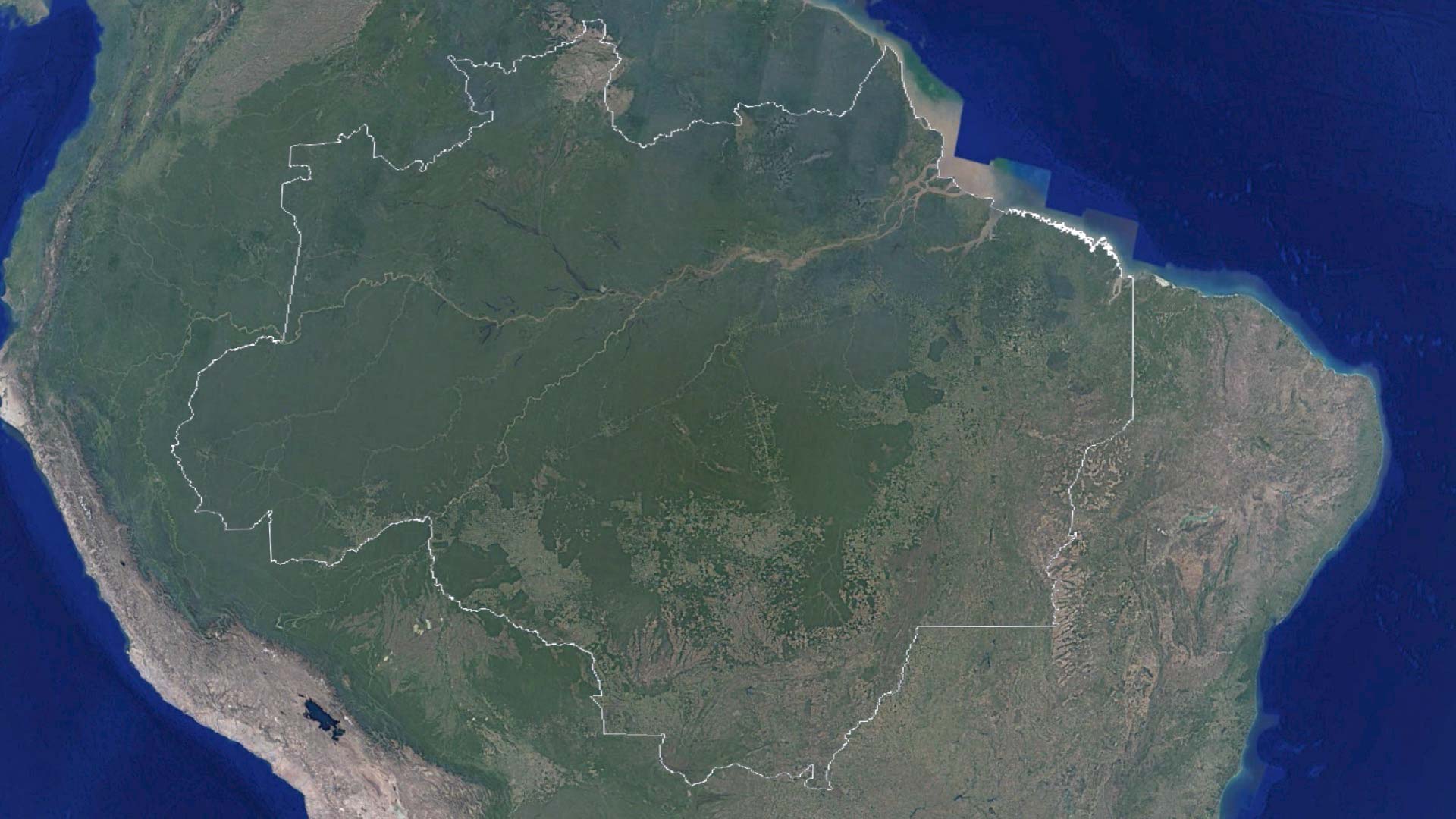

Today, it runs from Cuiabá, in the heart of the grain basket, to Santarém, a muggy port city on the Amazon River. As it snakes north, it cuts a path not only through the country itself, but through Brazil’s conflicting ambitions: to transform itself into a first-world economy, on the one hand, and on the other, to protect and preserve what is left of an ecosystem that recycles a fifth of the world’s rainfall, holds 150 billion tonnes of stored carbon, and is home to 15 per cent of all the species on Earth.

The outsize scale of the farms and the trucks was fitting, given what this region represents for Brazil. The government adapted soy plants for this climate in the 1970s, and farmers began to move here from the south. But in the last 15 years, as global demand exploded – primarily for soy to use in animal feed, and for livestock to nourish a new middle class in China and other emerging economies – the wealth, and the political importance, of this area began to grow.

Soy products accounted for $40-billion in exports last year. As Brazil has lived through its worst recession in nearly a century, this was one sector that continued to expand. That gave farmers and landowners, always a strong political force here, an even greater influence.

For the last 45 years, the southern border of the forest has been pushed steadily back. From the time of the generals, and into the 1990s, this was explicit government policy. The transition to democracy came just as domestic and international pressure about preserving the rainforest began to mount. Brazil took a new tack, saying it would try to control deforestation – assisted by an international fund, backed primarily by Norway, that recognized that the country was being asked to preserve forest cover of the kind that rich nations such as Canada had demolished in their own path to development.

Then came an interesting confluence of events that complicated Brazil’s relationship with deforestation. In 2002, Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva, known as Lula, was elected Brazil’s president. His first years in office coincided with a surge in global commodity prices that made Brazil richer, and Lula popular – and fuelled a surge in forest clearing to make way for cattle and soy, much of it shipped to world markets along the BR-163. Lula was sensitive to the international criticism about the Amazon, and he tasked his environment minister with sorting it out. Marina Silva, a protégée of the assassinated environmental activist Chico Mendes, drew up a transformative plan to change the way Brazil managed its forest: The key was robust police enforcement, employing those satellite images. For the tricky issue of Amazon highways, she put forward a plan called the Sustainable BR-163, which proposed the road be used to enable development but be carefully managed to control deforestation. A key measure involved turning huge areas of land along the road into “Conservation Units,” removing them from the land speculation market.

Ms. Silva eventually quit cabinet, disillusioned – she’s running for president herself this year. But her plan was tremendously successful. Deforestation fell by 58 per cent during her time as minister. Brazil continued to lose, on average, 9,600 square km of the forest, the size of Cyprus, annually – but the downward trend, even as GDP and income rose, was a powerful endorsement of sustainable resource management.

Yet starting in 2014 – as political turmoil and corruption scandals engulfed Brazil – deforestation rates suddenly shot up again, likely a result of the perception that there would be few repercussions for breaking the law. Dilma Rousseff, Lula’s hand-picked successor, was impeached in 2016 after six years in power, and replaced by her vice-president, Michel Temer, a long-time patron of rich landowners, soy farmers and ranchers. Mr. Temer himself was soon ensnared in scandal, and turned to those ruralistas to ensure his survival, by proposing to ease restrictions on everything from mining to ranching in protected forest. “All of the gains we had in the past 30 years, creating environmental safeguards, laws that organize land occupation – are being exchanged with this rural elite, they’re the bargaining chip to keep Temer as president,” Ane Alencar told me, before the road trip. She’s a scientist who helped write the plan for the Sustainable BR-163, and a co-founder of the Amazon Environmental Research Institute.

Here, too, there are vast fields, recently harvested. But there are trees, too: More than a third of Mr. Ferrarin’s land – 5,300 hectares – remains primary-growth tropical forest.

It is not because he is a bleeding-heart environmentalist, he was at pains to make clear, that he has preserved those trees. He believes the government will eventually pay out to reward those who protect the forest cover; in the meantime, the trees help keep his water sources running.

He believes that farmers like him should be compensated through a global fund for the trees they leave standing.

It’s not just me who needs to breathe fresh air – it’s the whole world.”

But not all of them. “I’m not in favour of zero deforestation – I’m in favour of legal deforestation,” he says. “The world needs food. No one can live from forest.” And Brazil needs the exports. “Agribusiness,” he says, “is what’s keeping this country afloat.”

Under Brazil’s Forest Code, the owners of property in the Amazon can clear only 20 per cent of their property; the balance they must preserve, or restore to forest if it was previously cleared. There was an amnesty when the code was brought in 2012, which is how Mr. Ferrarin gets away with having less than that. Besides, he is disputing whether his forest technically would be Amazon, claiming he is in the transition zone from a savannah-like biome called the cerrado, an argument that has increasingly found favour with environmental authorities under the Temer government.

I came here in 1978 encouraged by the federal government to open new frontiers and occupy the Amazon.”

He built Esperança by acquiring a series of small properties. “When I bought it, I had to clean up the rest of the native vegetation,” he said. By limpar, clean, he meant cut down. He stopped the truck at one point to show us a clump of three grand trees. “I left those,” he said proudly. A shifting, tail-swishing clump of cattle stood beneath it, each trying to keep within the small circle of shade the trees cast.

There are twice as many cows as there are people in Brazil – but this country has the world’s least productive cattle industry. Canadian farmers raise, on average, seven cows per hectare; here, they raise just one. Forging new pasture for cattle is the single biggest driver of deforestation – responsible for 66 per cent of it. But that statistic can be deceiving. Often it isn’t the push to graze more cattle that drives farmers to fell trees. Instead, cattle are used to declare de facto ownership of land that has been purchased or occupied. Brazil’s land-titling system is intensely bureaucratic, extremely slow, and often simply absent; just 30 per cent of landowners in the state of Pará, where we were headed, have legal title to their land.

And because people who don’t have title to land can’t rent it out – or sell it – keeping cattle makes it productive, without anyone having to do much: Brazil’s cattle are turned loose in fields of scrubby vegetation and left for weeks at a time under minimal supervision.

He told us about his part-time role as an evangelical pastor. He told us how proud he was of his daughters, both college graduates – he never had the chance to go past grade school. His children are raising their own families in the town of Sinop.

And after we had been talking for several hours, and the harsh lines of the pastures had softened in the late afternoon light, Mr. Weiss chuckled and offered to “confess.”

When first he came north, he made a living by operating heavy machinery, he said, and then he saved up enough to buy the equipment himself and began to hire himself out to clear farmland: two tractors, and a chain slung between them – that’s how the 50-metre trees of the Amazon were brought down. And that’s how he made the money to acquire Esperança.

He quit clearing in 2005, when the government’s new regime of enforcement kicked in. “I never did any work without documents, nothing illegal,” he said. The top environmental official in the region was a friend of his, and warned him he could end up behind bars if he cleared land for people with fake permits. “So I got out of the business – other people went on working on whatever terms.”

Not that Mr. Weiss was opposed to a little creative sidestepping of the law, once he became a farmer. When warnings began piling up that he wasn’t meeting his obligations to replant the cleared areas of his property, he took a stack of them into the office of his pal and dumped them on his desk. They had a gentleman’s agreement that the warnings and fines would “go away,” he said, and he has simply ignored them for years.

But what about his cattle business? In 2009, Brazil won a commitment from major beef producers that they would not purchase cattle raised on illegally deforested land. But Mr. Weiss said with a shrug that he has no trouble selling his animals.

He does not have formal registration of his property; to get it he would have to reforest, something he has no intention of doing. “It’s not my responsibility.” He is focused instead on modernizing his ranch – he’s building up from three cows per hectare to six. And he is converting some pasture to soy fields.

The environmental lobby drives him bonkers. The stars of Brazilian soap operas are always collecting signatures on petitions to preserve the forest, he said, without thinking for a minute about where their food comes from. “They won’t pay a penny to reforest. I’m the one whose pocket it’s supposed to come from … I came here and built something, and now I’m the villain.”

At midday, we pulled up to a skeletal shed in the middle of Jamanxim National Forest.

The ICMBio agents leapt down from their pickups and homed in on four men sitting out the heavy midday heat under the rough metal roof, while the police fanned out to form a semi-circle perimeter.

The men were cooking beans on a gas ring connected to a tank of propane; the blue flame hissed and the steel pot juddered. At first, the rattle from the pot drowned out all the other sounds.

One of the agents, Nilton Barth Filho, stepped over to the tank and turned the flame down. For a second I thought this was courtesy: If they were going to interrogate these men, they would make sure lunch didn’t burn. But as the noise died away, a second sound was audible – the drone of an engine somewhere in the forest behind us. Mr. Barth Filho’s head snapped up as he heard it, and then he and three colleagues bolted toward it.

The sound of the engine stayed steady – so it wasn’t loggers with chainsaws. It was a pump: garimpeiros panning for gold.

Both of the agents were right, in their way. The garimpeiro do drive deforestation across the Amazon. But their environmental impact is dwarfed by that of the legal mining industry, which has a large – and growing – presence in the rainforest.

There are active legal mines, exploration sites or purchased concessions on almost one million square kilometres of land in the Amazon; mining in this region was worth four per cent of Brazil’s GDP in 2016, or $32-billion. Mines must undergo an extensive environmental licensing procedure, and companies are required to later “restore” the area they have mined, which means the impact of mining can appear relatively small, compared to farming or logging.

But new research has found that mining leaves a significant footprint. Australian ecologist Laura Sonter recently demonstrated that 9 per cent of the forest loss between 2005 and 2015 was due to mining. That’s 12 times more than occurred within mining lease areas alone. The additional deforestation comes from urban areas that grow up to house the work force, industries that expand to serve the supply chain, and big infrastructure projects built to support the mine.

Today, mining is not permitted in protected areas. But last August, President Temer introduced legislation to permit mining in a 28,700-square-kilometre reserve called RENCA, in the northeastern Amazon, a region that is home to three First Nations and also acts as a huge carbon sink. In the wake of a global outcry, he withdrew the proposed law. But RENCA was just one small piece of a much bigger debate about mining in the forest: Another five million hectares of land – equal to the size of Costa Rica – are the subject of bills before Congress seeking to lower their protection status to allow mining.

Given the scale of the industry, it was easy to understand why Mr. de Jesus felt that busting a few men panning for gold was pointless. But they weren’t having much luck with ranchers and loggers that day, either.

The people who came here to colonize the area really see the forest as a supplier of resources to be exploited.”

“We can’t get them,” Ms. Ferreira chimed in, her voice flat with frustration. “Eighty per cent of the time, we know – but we can’t prove it. They put the land in someone else’s name, and we issue fines, and nothing happens – they toss the fine in the drawer. The only person who ever pays the fine is a small land-grabber who is afraid of the attention.”

Landowners with outstanding fines can’t get access to government credit programs – that’s one of those enforcement measures brought in at the beginning of the turnaround period, in the mid-2000s. But for a nominal fee, or the use of some land, they can easily find someone to put their name on the property. “Brazil’s problem is impunity,” said Ms. Ferreira. “If people who break the law ever got punished, it wouldn’t just keep happening.”

Mr. de Jesus chimed in. “The only way they get punished is that we destroy their equipment, like their tractors and their pumps,” he explained – something ICMBio agents have been authorized to do since 2009, when they come upon an environmental crime. “That,” he adds, “is when our work gets dangerous.” A law currently before Congress, proposed by the head of the ruralista lobby, would bar agents from destroying equipment.

When, after hours of this, we finally encountered the garimpo, the agents were jittery with adrenalin. But even as they smashed up the equipment, it was clear they weren’t striking much of a blow for the forest.

“Did you know this was Jamanxim Forest and you can’t mine here?” she asked Mr. Lima.

“No,” he replied, “I never heard that.” He was standing with one foot on an old wooden sign that identified the area as protected; he couldn’t read that, either.

“The government speaks pretty words about protecting the forest – but we will lose 50 per cent of our budget next year,” said Mr. Fucks. “We need [more] employees and three times as many vehicles. We only have what we do because foreign governments donate them … We’re losing. But if we had three times as many people, we could win.”

Ms. Ferreira, peeling off her bullet-proof vest at the end of the day, questioned whether beefing up their ranks would really make a difference. The most powerful politicians in Novo Progresso, she pointed out, own the farms inside the forest. “If the punishment was serious – if the law applied here … Even if we had 100 vehicles and all these people, it wouldn’t fix it. Because it’s politics.”

“Would you like tea? It’s mate, we grow it ourselves.” This was the gracious welcome from a politician at the centre of this ongoing conflict when we went to see him the next morning. At Novo Progresso’s unpretentious single-storey city hall, we were ushered in to meet the vice-mayor, Gelson Dill. (The mayor, Ubiraci Silva, does not meet with journalists. The fact that he is facing $515,000 in fines for environmental crimes may have something to do with this.)

It was just last year that Mr. Dill was elected to the number two job in this municipality, which at 38,000 square kilometres is more than half the size of New Brunswick; but he has served as a municipal councillor for almost as long as he has been a farmer, because, he says, producers must have a voice in politics. He was eager to talk to us about the development challenges in the region: Trucks spent more than 10 days parked on the BR-163 near the city last year, he said, when the rains turned the highway to mud, and the government had to airlift in supplies. Only a fifth of local producers have been able to register title to their land because the process is so slow and complicated, he complained.

[The city] is strategically located and has a huge growth potential both in agriculture and mining segments.”

I broached Mr. Dill’s own environmental record gingerly, but it turned out he was eager to discuss the subject. He breezily confirmed what I’d heard, that he owns a farm inside Jamanxim National Forest. But he said he owned it before the land was declared a Conservation Unit – and that it was part of a family enterprise in the area that included logging and sawmill businesses. The logging was rendered illegal overnight when the area was given protected status. His brothers gave up and moved, but he kept the ranch, on the footprint they already occupied, he said.

The previous government, of Ms. Rousseff, denied him compensation on the grounds that he had occupied the land illegally. But in the Temer administration, he and the owners of the other 250 ranches in the protected forest in Novo Progresso have found a newly sympathetic ear. By recategorizing 400,000 of the 1.3 million hectares of the Conservation Unit, he says, the government could address the uncertain situation of 95 per cent of the people living in the protected area. The farmers are negotiating with the government over precisely how much land, and which areas specifically, would have its conservation status downgraded, but he said he expects the law to change soon.

Environmentalists and protection officers abhor the plan – not just for the amount of forest that would be lost within the rezoned area, but for the message it would send to land-grabbers and speculators in the rest of the country: If they occupy and clear protected land, and settle in, sooner or later they will be given ownership – and the right to deforest. Ms. Alencar, the conservation scientist who drew up the original Sustainable BR-163 plan, put it this way to me before we set out on the drive: “If the government says, ‘We will change the limits of Jamanxim National Forest, and everyone that is there is allowed to be there’ – imagine what will happen to the 47 per cent of the Brazilian Amazon that is some kind of protected area.”

But Mr. Dill made his sound like an eminently reasonable solution. “Their goal was to suffocate the producers in the Conservation Units,” he said of the Rousseff government – but that would be bad for the forest. “The producer ends up not trusting the state, and committing environmental crimes and clearing new areas.” Under his proposal, farmers whose properties are regularized would be motivated to maintain their status as good citizens, he said.

“There are more than 19 million hectares of forest in our region – and we’re asking for less than one million hectares, to resolve the conflicts.”

Mr. Dill frankly conceded that he has received fines on other properties he owns outside the forest. The policy that prevents slaughterhouses from buying animals reared on irregular land such as the forest farm ought to have made the ranch unviable. Mr. Dill puffed out his cheeks and described that restriction as little more than an irritation: He raises his cattle to nearly full-grown, then hands them off to a farmer whose land lies outside the protected area – after which they’re sold into the supply chain that promises consumers rainforest-free beef.

The source of much of the violence is the trees, which in this region are felled not only to make way for other industries: This is an epicentre of illegal logging. It’s a lucrative business, worth an estimated $288-million – at least half the timber harvested in Brazil is illegal. Logging here isn’t the kind of clear-cut that Canadians might envision. Illegal loggers target individual high-value trees, such as a single ipé, 45 metres tall and nearly two metres around, that will produce $5,000 worth of wood. It might be growing in a conservation area – a national park or forest – or on union land, which is like Crown land in Canada, owned by government but not zoned for protection. Or it might be on private land, which under the Forest Code can’t be legally logged.

You might think, so a tree or two is taken here or there – comparatively that doesn’t seem like such a big problem. But logging, like mining, has an outsize impact. “It’s deforesting activity that incentivizes,” is how Marco Lenti, who has been researching the business for more than 20 years and currently manages the forest file for the World Wildlife Fund in Brazil, explained it to me. Once loggers open a road, they are often followed by hunters, and then by garimpeiros, who use the opened track to explore for gold. Then comes the wholesale clearing: The land is set alight, the cheapest and fastest and easiest way to clear the vegetation. “Logging is the starting point,” Mr. Lenti said, “of colonizing the forest.”

It’s also deforestation that degrades: The logged patches may appear on those satellite maps as untouched. But biologists have discovered in recent years that the extraction of even a small number of trees has a mammoth impact on biodiversity and the health of the forest.

There were more fires in the Amazon in 2017 than had been recorded since record-keeping began 19 years ago – more than 160,000 in September alone.

The loss of the big trees also affects the natural cycles of the lower ones, and throws the whole ecosystem out of whack. We are only beginning to understand how damaging this is. New, more sharply focused satellite monitoring shows that from 2007-2013, some 102,000 square km of the Amazon were degraded – more than double the area deforested. A study of the biodiversity in degraded forest in Pará found that twice as many species have been lost to degradation as to deforestation.

As with so much else in this country, Brazil has, on paper, a plan to control illegal logging. A licensing system is meant to ensure that timber sold in Brazil or exported is legal – but the system is laughably inefficient, Mr. Lentini explained, and easily corrupted. To obtain harvesting permits, landowners bribe officials; or sell illegally harvested trees, claiming they have come from other land they own and are permitted to log; or fudge documents coming out of sawmills. Fake papers are so easy to come by in towns such as Trairão, he said, that he has bought them himself, in a matter of minutes.

They spent 15 years there, trying to build up a farm – but a neighbouring soy-plantation owner kept trying to buy them out. (It’s illegal but common for people settled through INCRA to sell their land). Eventually, he took to burning their fruit and nut trees, she says. When police ignored their complaints, they headed farther north, thinking they would have more luck in this area where agriculture is still small-scale. They found the land near Trairão – INCRA wouldn’t resettle them officially, but no one complained when they began to set up a home there.

And instead of clearing trees, they planted more. They began to harvest caucau and cashews, and seeds they sold to reforestation projects. These were ideas she learned from her mother, who raised 12 children on what she gathered in a small woodlot. “People said at first that we were crazy,” Ms. Pereira said, when she welcomed us into their airy house, nestled in a grove of trees. “But then they saw what we were doing and many of them wanted to start doing the same thing.” Ms. Pereira set up an association, teaching women in the community how to make a living from the forest. Some of their husbands switched to “extraction,” as it is known, as well.

The logging bosses did not appreciate any of this: They didn’t want to compete with her for manual labour, and they didn’t like the ethos she was spreading about how the trees had more value left alive. Neither did they like all this talk of living self-sufficiently from the forest. When the environmental police made a major raid on the loggers in the area in 2013, and burned the logging equipment, the owners blamed her for tipping off the authorities – she says she did nothing of the kind, that she had, rather, been hoping to win people over gradually.

But the reprisals came almost immediately.

Because of our work here and due to the concentration of illegal loggers here, we received death threats.”

A woman warned her that four local loggers’ associations had put up $1,500 each to pay for a hitman to kill her and her family. A short time later, on a rainy evening, several trucks pulled up in front of their house, and 12 men, draped in guns and ammunition, appeared at the door. Knowing the neighbours were too far away to hear her scream, Ms. Pereira recalls with a wry smile that she and Mr. Alves instead invited them in; she made them juice from the fruit she’d harvested.

The loggers said they were there to make a “deal.” She said she wasn’t interested. The leader told her, “Look, if one of my workers loses his livelihood because of you and they come here and do something to you or your husband – don’t blame me.”

“Is that a death threat?” Ms. Pereira says she asked him.

“I’m just telling you, poor people like you only make money when they die,” he replied.

“So kill me now,” she said. “Because if you don’t, I’m going to make a criminal complaint against you all.” It was, she says, resignation rather than bravado: She was convinced that they would, in fact, kill her.

For reasons that still mystify her, they didn’t. They put down their juice and drove off into the rain. “They could have done whatever they wanted – we were alone there, and there was no way out. … They have killed so many people and no one hears about it. No one has the courage to talk about what happens here. Here there is justice for the rich, my dear, but not for the poor.”

Reporting the threats to the law yielded little – no local police station would open a case against the comparatively wealthy and powerful loggers. Gunmen continued to pull up and circle her house periodically on motorbikes. And although federal police finally got involved, the best they had to suggest was that the family move away. They refused. A sort of uneasy détente developed: They abandoned the effort to win others over to extractivism. But they stayed put.

We were asked to change our names and leave the state and move to another, but we are not criminals, we never killed anyone, so why should we leave?”

“If we leave, we’ll lose what we built here, and they’ll keep killing people and nothing will change,” said Ms. Pereira “We already ran from Mato Grosso and we’re not going to run again.”

Ms. Pereira sees the dense forests that remain in Pará as a sort of last stand for the country. “We don’t want what happened everywhere else in Brazil to happen here.”

Their small farm, an oasis in the forest, where the chickens fussed at our feet and flowered vines crept over the house, presented a weird contrast to the dark story Ms. Pereira told. A fierce rainstorm blew in before dusk and she urged us to get back on the road, not to linger. Mr. Alves sketched out a shortcut back to the BR-163 – a road built by loggers to get their loads to the highway more quickly – and we headed off.

In Itaituba, a city of 100,000, we checked into a hotel – it could charitably be called “modest” – where rooms were running at more than $200 a night. In the morning, when I saw the breakfast room full of men in the uniforms of construction companies and hydroelectric plants, I understood the hefty rates: Itaituba is a boomtown in the making.

By now, 10 days into the trip, my shoulders ached from yanking the steering wheel around the giant potholes, my eyes stung from the smoke, and the whole world felt like it was coated in a palette of unremitting greys and browns.

So when we picked up Alessandra Korap at her house in a small Indigenous community on the edge of town in the early morning, and parrots congregated noisily in the mango tree above her house, it already felt like a respite.

She directed us out of the town and onto the Trans-Amazônica, the east-west highway.

We drove west for an hour inside the Amazon National Park before turning onto a dirt road leading down to the banks of the Tapajós. A line of boats in varying states of disrepair littered the shore; Ms. Korap told us they belong to garimpeiro who use them to dredge the river bottom and travel to access points for sites inside the forest.

Before long, there was the growl of a motor, and a teenager from Ms. Korap’s community piloted a simple outboard to the shore. He lugged aboard the gas we had brought, piled us in,

The constitution adopted in Brazil in 1988, following the end of the dictatorship, guaranteed the rights of Indigenous people to their land, and in the 1990s the government began the process of identifying traditional Indigenous territories and handing them over to limited forms of self-government. There is archeological evidence that the Munduruku have occupied the region of the upper Tapajós for hundreds of years. In the late 1990s, they began the process of trying to have the land demarcated, as the process of official recognition is called in Brazil. And they fell into a bureaucratic nightmare that dragged on for more than a decade.

Finally, in the last hours of Ms. Rousseff’s administration, some 173,000 hectares were provisionally identified for demarcation. But when Mr. Temer took over, he froze the process again. In 2014, the Munduruku did the physical part of the process themselves – cutting a border around their territory through the jungle. That didn’t, however, give them legal rights to the land.

And that matters: Officially designating the land as Indigenous would threaten one of the most ambitious infrastructure projects in Brazil.

The hidrovia is a plan for 49 separate dams on the Tapajós and its tributaries – meant to quell the rapids and create a 2,200-km stretch of placid water on which grains could be moved north to the Amazon River – on barges that hold 50,000 tonnes, compared to 40-tonne trucks. Among the investors in the project is China’s Three Gorges Development Corporation.

When operational, the dams would generate 29 gigawatts of electricity, equal to 25 per cent of Brazil’s current usage. The biggest of the dams would be more than seven km across and require clearing nearly one million hectares of forest. The Munduruku territory would be obliterated.

The Munduruku have been fighting the dams for five years now – in a canny campaign that they focused not on Brasília as much as on Europe, where the citizens of countries sympathetic to Indigenous people might put pressure on Brazil.

They have managed to have the building of the first two stages suspended while the Supreme Court considers whether their claim to the land is enough to stop the project. But if they don’t have demarcation, they cannot claim Indigenous land. And in the hotel lobby in Itaituba, as men in suits and men in industrial coveralls bustled past me in all directions, the prospects for such official recognition seemed remote indeed.

Our young boat pilot nosed us into a dent in the trees, and Ms. Korap led us ashore and along a short jungle path to a clearing.

The cacique welcomed us graciously and sat us down to explain why the Munduruku won’t get their right to their land recognized in today’s Brazil.

“We used to think it was the dams that were the issue – today we see that the dams are just the foot in the door,” he said. “After they build the dams, other projects come after it, projects to export soya, mines, ranches, sawmills.” Already Munduruku land is peppered with garimpo mines. “But we know the garimpos, the little guys, they won’t stay. It’s the big foreign mines who are going to get control of this region.”

Just the day before, Mr. Saw told us, he and some of his family had been out hunting in the forest when they heard illegal loggers at work, on the Indigenous land – but could do nothing to stop them. “We can’t do anything. We’ve been repeatedly threatened by them. If we want to survive any longer, we have to keep quiet. We can only report them to ICMBio for them to enforce the law – but they aren’t able to do it.”

It would not be difficult, in his village, to romanticize the role of Brazil’s Indigenous people in protecting the forest – to see their way of life as holding some sort of key to human survival.

On the day we spent in Sawré-Muybu, Mr. Saw and his family moved easily through the tangled trees and vines, racing across slim branches balanced over swamps, moving swiftly up and down the hills at the riverbank. In late afternoon, children lined up to plunge one after the other into an ice-cold stream.

Yet, as Chief Juarez himself observed, there are Munduruku working in the garimpo on their land, and Munduruku who do illegal logging. They do it, he said, for money. He does not want his people to live entirely isolated in the forest: They need better health care, and better education, and options for young people.

But the change must be on their terms, he said – and those are terms that settler Brazil does not seem to grasp.

We know that nature gives life to everybody, both Indigenous and white peoples.”

Santarém’s port buildings are a bulky, modern contrast to the low, gentle sprawl of the rest of this city, where, nearly 500 years ago, Jesuit missionaries began to build a town on the site of a settlement of Tapajós Indigenous people. Today Santarém has an economy growing at three times the national average and expects its population to double, to 600,000, in the next three years.

In the morning, we went to see Higo de Sousa – a deputy to the state’s top environmental official, whose office is 1,500 km away in the capital, Belém. He inquired about our journey, and when we told him of the smoke and the craters on the BR-163, he just laughed.

Mr. de Sousa was eager to describe the many ways the state is attempting to control illegal activity in the forest. In the same way that slaughterhouses have to say where they get their cattle, and Cargill has to buy soy from producers that have registered their land, the government wants to make gold buyers verify their sources of ore, he said.

But the longer we talked, the more Mr. de Sousa’s outward optimism seemed to fade. I told him about how the cattle ranchers we met described the way they circumvent the system. Timber buyers, he acknowledged with a sigh, do the same: “That’s our life – we set up a process, they find a way around it. There are 853 garimpo sites around Itaituba alone, he added. “You can’t stop it – there are millions of these anthills in the forest – by the time you get there, they’re hiding in the woods.” Not long ago, he travelled two days by road and boat with a two-person police escort to inspect a huge plantation being carved into the forest illegally. When he got there, he was confronted by an armed militia. “So we turned around and travelled two days home again.”

By the time we had been talking for a couple of hours, Mr. de Sousa had boiled the situation down to a question of power. “The big agricultural producers, the ones with the most capital, are the ones at the front of politics here,” he said. And they are the ones who will determine what happens to the forest. “When you see it from outside it doesn’t look so complex. When I started in this job, I thought, ‘Okay, let’s fight the loggers, the miners, the ranchers’ – but when I got a good look at it, I was just a small dot in the giant canvas.”

Mr. de Sousa concluded, half-joking, “The planet is depending on me.” Then he buried his face in his hands. “For the love of God …”

I also knew that some of the measures that would make a real difference for preserving the Amazon are relatively straightforward. That regrown forest, for example, could be monitored. The satellites that sweep over the Amazon take no pictures of regrowth: Once a patch of forest is marked as cleared, it is subsequently skipped. Something as simple as turning a camera on it now would allow the government to track what is regrowing.

Brazilian agriculture is hugely inefficient, something I’d been reading on paper for years but understood in a new way when I drove through the endless fields of newly cleared pasture, right next to previously cleared land that had been abandoned. Brazil does need a stronger agricultural sector; it is a vital part of the economy, just as Mr. Ferrarin and the other farmers insisted.

With technical assistance to farmers and ranchers – teaching them about crop rotation to prevent pasture degradation, for example; and using water tanks, instead of ponds, for cattle – the sector could expand without losing another hectare of forest.

At the same time, by stripping corruption and bureaucratic inefficiency out of its land-titling system, Brazil could deliver ownership documents to Brazilians who are already legally farming in the Amazon, turning their farms into collateral for credit that they could then reinvest to increase their productivity. And the government could stop settling poor farmers in the forest – people with no assets and no technical support who have little choice but to clear land for cattle, because they have no other way to make a living.

For the more than half of farming that is already made possible by government credit, such credit could be conditional on farmers demonstrating compliance with the Forest Code. And government spending – on credit, but also on infrastructure such as roads and bridges – could be prioritized for municipalities that are operating within the Code: The likes of Vice-Mayor Gelson Dill’s Novo Progresso could be blacklisted until a majority of properties are compliant.

In addition, the research institute Imazon found that a quarter of all deforestation in the Amazon in 2016 took place on public land that hadn’t been zoned. As a result, no one is assigned to monitor what happens on that land. By converting it into Conservation Units and recognized Indigenous territory, the government could dampen the market in land speculation.

Marco Lenti of the World Wildlife Fund described as “reasonably well managed” the 2.5 million hectares of Amazon that are currently licensed and used for sustainable logging (four or five of the oldest trees per hectare are removed each year). Those swaths of forest are safe and monitored. But there is so much consumer concern now about dirty supply chains, and about rainforest wood in general, that people don’t want to buy even from such legal producers, he said. “I think we need to use the forest to give it value,” he said.

These steps are not easy, but they are manageable, in the context of what Brazil has been able to do already. But what I understood only once I’d driven the road was how intense are the pressures to do something different.

The 30 million people – almost a Canada – who live in the forest want better lives, and so do millions more Brazilians.

They see a resource whose value is to be maximized immediately. They have willing partners, in China in particular, ready to fund the infrastructure that guarantees a steady flow of food, and in companies such as Cargill, ready to process it in the supply chain of their giant transnational businesses.

Almost everyone I met on our journey talked about the price they were being asked to pay – to protect the forest, or to develop it. The ranchers and the farmers asked why the cost of stored carbon and recycled rain should come out of their pockets. The Munduruku wonder why their survival must be bartered for a growing economy that will fund Brazil’s pensions and universities. Should Western consumers bear some of the price, too, by paying more for sustainable rainforest products, for wooden decks or soy-based pet food or steak? Everything – wood, soy, cattle – raised on farms compliant with the Forest Code costs more, because because it comes from a reduced area of productive land on property that's mostly forest. And auditing those supply chains costs money, too.

One day not long after our trip, I sat in my office in Rio and clicked open the latest satellite feed of images of the Amazon. I thought about how silent and how clean it looked from above, with wisps of cloud across the images – and also, once you know what you’re looking at, how crowded. And I remembered Mila Ferreira, the environmental-protection agent, and something she told me when we were standing in a smouldering field, with bemused cows watching us eating a pineapple we were given by a friendly, unhelpful farmer.