The Canadian army desperately needed men like Scott Smith.

A hard-nosed counsellor who worked with troubled teens in the Vancouver Island wilderness, he looked the part of a soldier. He was tall and muscular, with a gruff appearance that concealed his fun-loving side.

Cpl. Scott Smith was a counsellor at a wilderness camp for troubled teens on Vancouver Island before joining the military in 2009.

Courtesy Smith family

When he enlisted in 2009, Canada was ensnared in an arduous combat mission in the southern Afghanistan province of Kandahar. Confronted with a defiant Taliban armed with assault rifles, rocket-propelled grenades and homemade bombs, Canadian soldiers were dying at a rate not seen since the Korean War.

Corporal Smith went to the battle-scarred country wanting to make a difference, supporting the training and fighting of Afghan security forces during a nine-month tour.

He came back a frayed man, his mind ravaged by the eternal replay of war. He started drinking more and spending less time with his wife and two young boys. Large crowds spooked him. Even an outing to a pumpkin patch he found unnerving.

Last December, two years after returning from Afghanistan, Cpl. Smith, who had counselled others against suicide, ended his own life after a military Christmas party. He was 31 years old.

"I knew that the military was part of our life till the end," says his grieving wife, Leah. "The end was a lot sooner than we expected."

The mostly NATO-led Afghanistan combat mission, which wrapped up in 2014 after 13 years, claimed many Canadian lives: 158 soldiers, one diplomat, one journalist and two civilian contractors. Two of those soldiers took their lives in theatre; four others were suspected to have done so.

But that's only part of the story.

The Globe and Mail has learned that at least 54 soldiers and veterans have killed themselves after serving in the Afghanistan war. The tally comes partly from e-mail records created by the Department of National Defence and the Canadian Forces in 2014, in response to questions from The Globe, but they wouldn't release the suicide count.

Details came to light only after the newspaper obtained those records through the Access to Information Act eight months later. The 162 pages of e-mail communications show that The Globe's request was initially sent to 30 military and government e-mail addresses and was processed for nearly two months. At some point, a decision was made to keep the suicide tally secret.

The Globe identified other deaths through poring over more than a decade's worth of military-related obituaries, and then confirming, in interviews with soldiers' families and members of the military, that those deaths were in fact suicides.

The effects of the Afghanistan mission were clearly a factor in some of the suicides, though it's unclear in how many. Data collected by the military and by The Globe and Mail show that in the final years of the operation, suicide became a far greater threat to Canadian troops than did insurgents and their weapons. From January, 2011, to April, 2014, two soldiers were killed in combat in Afghanistan; in that same period, at least 29 took their lives after returning home from war. (The exact count is uncertain; the federal government doesn't regularly track suicides of veterans and has incomplete records on reservists, who made up more than one-quarter of Canadian troops in Afghanistan.)

"They don't have a grip on the suicidal veterans," contends former veterans ombudsman Pat Stogran, a retired colonel with the Princess Patricia's Canadian Light Infantry. "If troops are coming out of the battlefield so damaged that they are going to kill themselves, to me it's an extension of the conflict and it's an extension of the Force-protection obligation."

Suicide is complicated. Rarely can families answer even the most basic questions: "Why?" and "Why then?" Rarely can investigators say, in any definitive way, how the death could have been averted.

But prevention, at least in some cases, is possible. And there are lessons in each death – for the military, which is responsible for delivering health care to soldiers; and for the Canadian government, which sends men and women to war and has pledged to look after former soldiers when they are released.

Although the military acknowledges that mental illness is sometimes connected to a soldier's service overseas, it says it has not found a consistent relationship between deployment and increased suicide risk.

Both the Canadian Forces and Veterans Affairs note that, over the past decade, both organizations have dedicated more money, staff and facilities to mental-health care, and they insist that they have strong suicide-prevention programs in place. Forces spokeswoman Jessica Lamirande also notes that, upon returning from Afghanistan, all soldiers underwent an "enhanced post-deployment screening process" to help identify possible medical issues – and suicide risk. As well, she points out, most of the 40,000 soldiers who served in the Afghanistan mission have not developed significant mental-health problems.

"We have made tremendous strides in supporting military personnel who experience deployment-related mental-health conditions, such as post-traumatic stress disorder," also known as PTSD, Ms. Lamirande says.

Most of the 54 soldiers and veterans who took their lives in the wake of the Afghanistan mission are unknown to Canadians. Soldiers whose suicides occur after their Afghanistan service are not recognized in the same way as those killed in the war. They are not part of Canada's Afghanistan Memorial Vigil – which includes plaques commemorating soldiers and Canadian civilians who died in the mission – to be permanently installed, along with a battlefield cenotaph, in Ottawa, likely in 2017.

In a sense, these are our forgotten casualties.

The Globe examined the lives and suicides of four men: soldiers Scott Smith, Jamie McMullin and Paul Martin and veteran Ron Anderson. All were husbands and fathers, tough infantrymen with the 2nd Battalion of the Royal Canadian Regiment at the Gagetown base near Fredericton. All fought for Canada in Afghanistan. All returned home broken, their minds and lives fractured by war.

Cpl. McMullin was the youngest, and the first to die, in June, 2011. Cpl. Smith, who had great ambitions for his military career, took his life most recently, in December, 2014.

These four soldiers' struggles with post-traumatic stress disorder, alcohol and the military's universality-of-service rule – which removes soldiers from the Canadian Forces if they are deemed unfit to deploy – demonstrate that the military and government are failing some of our most vulnerable troops. Cpl. Smith wasn't in treatment, because he feared that seeking help would torpedo his career, his family says; the other men were receiving therapy and medication for post-traumatic stress disorder before they died.

But the Globe investigation found that questionable decisions were made in their care, and in the handling of their army careers. A shortage of mental-health staff and support programs was also a persistent problem, as was the military's process for releasing mentally wounded soldiers from the army.

In one case, that of Sgt. Martin, a military inquiry into his suicide found that he was not "emotionally ready" to leave the Forces when he was scheduled for medical release. That same inquiry led to four recommendations aimed at boosting mental-health services and improving how the military deals with traumatic incidents. And yet, as a 2014 inquiry report obtained by The Globe reveals, the recommendations, delivered by three senior officials with the Canadian Forces, were rejected by military brass.

In the case of Cpl. McMullin, the military forgot to give his family the inquiry report into his suicide. The Forces didn't realize its mistake until contacted by The Globe. His death was attributable to military service, the inquiry concluded.

Canada's Afghanistan mission may have officially ended, but in reality it is far from over. The consequences of our nation's longest war are still reverberating through Gagetown and other military communities across the country.

Just ask the families of the deceased infantrymen.

"We spend a fortune training these soldiers to go over, and then we won't spend the money on them when they come back," laments Darrell McMullin, a career army man and Cpl. McMullin's father. "There has to be more money for the medical treatment when they come home. You have to be willing to put as much money into fixing them as you put into breaking them."

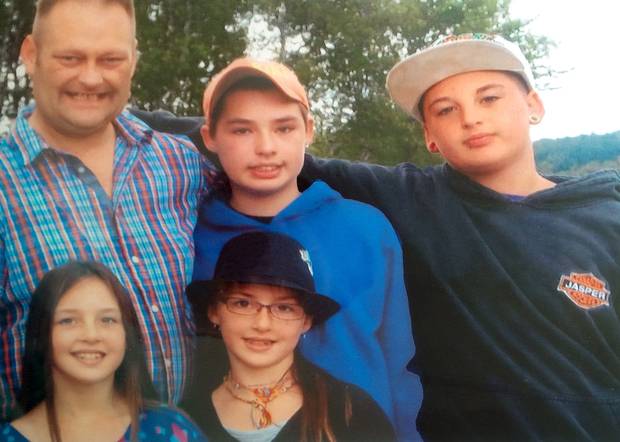

Cpl. Jamie McMullin dressed up for Halloween with his sons, Jake, left, and Hunter.

Courtesy McMullin family

Jamie McMullin, father of three. June 9, 1982 – June 17, 2011

Cpl. McMullin was a child of the military. He grew up around bases, first in Petawawa, Ont., and then in Gagetown, the second-largest military compound in Canada. His father worked there as a mechanic, fixing battle tanks. His mother, Brenda, was an administrative clerk at the base.

The Gagetown compound is drab and sprawling, occupying a swath of land about 25 kilometres southeast of Fredericton. About 6,000 people – military and civilian – work at Gagetown and its associated units. Opened in 1958, the base is the lifeblood of such nearby communities as Oromocto, Lincoln and Geary, where "Support our Troops" signs adorn the windows of fast-food restaurants, banks and barber shops. Roughly three-quarters of those towns' residents are Gagetown employees and their families.

The McMullins live in Lincoln, about a 15-minute drive from the base. Mr. McMullin had hoped his only boy would try a different career, perhaps learning a skilled trade. But his son wanted to jump out of helicopters and roll around in the mud. He wanted to be in the infantry.

Infantrymen (and they are still nearly all men) are trained for war. They are deployed to the front lines, asked to attack insurgents, protect civilians and defend territory. Armed with rifles, grenades, machine guns and other high-powered weapons, they are constantly on watch and on edge.

When Cpl. McMullin joined the military in November, 2004, his parents had just retired from the Forces. Athletic and outgoing, with short, dark hair and a big smile, Cpl. McMullin was the life of the party. He met his wife, Megan, in high school, but he didn't really get to know her until they were both in the military. Their relationship blossomed quickly.

Cpl. McMullin deployed to Afghanistan in September, 2008, part of a group dispatched from Gagetown to join Task Force 3-08. It was his first overseas tour, and he was excited. He'd trained nearly four years for this moment.

Cpl. Jamie McMullin deployed to Afghanistan in September, 2008, part of a group from the 2nd Battalion of the Royal Canadian Regiment at the Gagetown base near Fredericton.

Courtesy McMullin family

"He couldn't wait to go," his father recalls, seated in a rocking chair in his home. His wife sits across from him, her feet up, on a brown recliner. "Both [of us] being soldiers, we knew what it meant," he adds. "We were very proud that he was going and serving, but we worried every day."

The couple had reason to worry. The Afghanistan war was wounding and killing scores of NATO soldiers, Taliban insurgents and Afghan civilians. By the end of 2014, nearly 3,500 coalition soldiers would perish there, with Canada enduring the third-highest number of casualties, behind the United States and the United Kingdom. (Nearly 10,000 American troops are still in Afghanistan, supporting local security forces.)

A rugged country wedged between Iran and Pakistan, Afghanistan became a target of the Americans and their international allies after the attacks of Sept. 11, 2001, killed nearly 3,000 people – carnage orchestrated by Osama bin Laden and his al-Qaeda organization, which Afghanistan's Taliban regime had supported.

A U.S.-led coalition invaded Afghanistan and ousted the Taliban that fall. The Taliban were gone from power – but they were not gone. The Canadian military learned this firsthand in 2006, after it assumed responsibility for combat operations in volatile Kandahar. The Taliban had been steeling themselves for a fight and, that March, Canadian casualties began to climb.

Thirty-six Canadian soldiers were killed in 2006, compared with only one the year before. By the time Cpl. McMullin set foot in Kandahar in the fall of 2008, more than 90 Canadian soldiers had died.

The McMullins kept Skype open day and night on their laptop, just in case their son – who spent a lot of time on foot patrols and in the line of fire – might call. Once, he appeared on their computer screen around 3 a.m., in tears: One of his friends had been killed. The McMullins tried to comfort him; it was hard being so far away.

At some point, Cpl. McMullin was tapped to take over his friend's bed and his spot in the light-armoured vehicle. "That bothered him a lot," his father says. "He felt like he was replacing the guy."

In all, 12 of Cpl. McMullin's friends were killed in Afghanistan. He had a dozen poppies tattooed on his right arm to remember them after he returned to New Brunswick in the spring of 2009. The night of his homecoming, Cpl. McMullin woke his father up to talk; the elder McMullins were staying with Jamie and Megan.

"He was just very depressed about the things he had done over there that he couldn't get over," his father says. He declines to reveal details: "I told him I would never speak about the things he told me."

Already on sleeping pills prescribed during his tour, Cpl. McMullin looked exhausted. He was withdrawn and easily startled by loud noises. He angered quickly and often seemed on edge, waiting for something to happen. He started drinking heavily – rum, beer, whisky. He drank to forget. But the nightmares kept coming.

His parents suspected he had PTSD. Ms. McMullin knew what the mental illness looked like: Her husband had been diagnosed with it in 2004.

"He went through things a lot worse than I went through, and I did a tour in Croatia. I did Bosnia," Mr. McMullin says. "Jamie didn't come home. Jamie left his soul in Afghanistan."

Cpl. McMullin, who remained in the infantry, sought medical help shortly after returning. Diagnosed with PTSD, he was connected by the military with a psychologist for counselling and a psychiatrist for medication.

Although he was receiving treatment, his parents believe their son wasn't regularly taking his prescribed medication, which included pills for depression, anxiety, anger and sleep. And, in any case, he would have had to stop drinking for the meds to work properly. His parents tried to convince him to go into an alcohol rehabilitation program in Guelph, Ont. – the program has a contract with the military, and treats people struggling with PTSD and addictions. He told them he wasn't ready.

Two years after returning from Afghanistain, Cpl. McMullin tried to hang himself. Although one of his sisters found him in time to stop him, he became aggressive and the police were called. They took him to the psychiatric ward of a Fredericton hospital, where he stayed for five days.

That suicide attempt, in March, 2011, greatly alarmed Cpl. McMullin's family, but his care didn't appear to change greatly. His therapist recommended he get away for a week, his father says; Jamie wanted to go to the family's lakeside retreat in Cape Breton.

But Mr. McMullin says his son's time-off request was denied. Soon after, Cpl. McMullin was given a medical designation that limited what he was allowed to do in the army, a step that could have led to his discharge from the military. In the young man's eyes, it was a devastating blow. His father believes Jamie thought that his military career was over and that he didn't know how he would provide for Megan and their three sons – the youngest, Jake, about a year old.

The day he was told about his medical designation, Cpl. McMullin went golfing and drinking with a few of his military buddies. Megan was supposed to play baseball that night, but her husband got home late – so late that she couldn't make it to her game. He went down to the basement, to the corner where he hung his military uniforms. This was his personal watering hole.

Worried, Megan kept checking on him. At some point, she fell asleep on the couch with their son Hunter in her arms. She awoke in the middle of the night and went downstairs. Cpl. McMullin had turned his transistor radio on, tuned to country music. He had pulled out notes from his therapy and letters from schoolchildren, sent to him while he was in Afghanistan, telling him that they were proud of him, that he was their hero. Megan found him hanging from the rafters. He had just turned 29.

His death sent Megan and Cpl. McMullin's family into a spiral.

It's been four years since his suicide. Talking about his death still brings tears to his parents' eyes. Framed pictures of their son in military fatigues line a family-room table; a mini Canadian flag rests there, too. "For Jamie, to try to understand the pain he was in, he left boys that he absolutely adored," his father says. "I can't even imagine the place he was in, when he did it."

Darrell and Brenda McMullin believe the military’s medical system failed their son. ‘He fell through the cracks,’ his mother says.

Michelle Siu for The Globe and Mail

Many of the McMullins' questions about their son's medical treatment remain unanswered: They have not yet received the military board-of-inquiry report on his suicide, though it was completed in April, 2014, and The Globe obtained a heavily censored copy in July through the federal access-to-information law. Boards of inquiries are held in every suicide of active-duty soldiers. They take place at the soldier's home base and are closed to the public and media. Made up of members of the Canadian Forces, such boards are mandated to find out what happened preceding the suicide. Board members don't lay blame, but they can make recommendations to strengthen services and help prevent such an incident from occurring again. The National Defence ombudsman has been critical of the inquiries, recently saying that they are military-centric and difficult to understand for many grieving families. Long delays have also bogged down the process in the past.

In the report into Cpl. McMullin's death, the three-member board made four recommendations, but the content of those proposals was censored in the documents obtained by The Globe. What was not censored: the fact that his death "was attributable to military service."

The unredacted material notes one particularly traumatic incident. In mid-December, 2008, a light-armoured vehicle was hit with an improvised explosive device, killing three soldiers from Gagetown. "Recognized for his leadership and strengths, [Cpl. McMullin] was required to move to the affected section and fulfill the higher role and tasks of the deceased Section 3IC [third-in-command]," the report states.

As a result of The Globe's inquiries into the case, Forces spokeswoman Lieutenant Crystal Gayed says the military has taken steps to provide Cpl. McMullin's wife with a copy of the inquiry report and to organize a debriefing with the family as soon as possible. She says that the final report was approved when the inquiry's president transferred to Alberta from Gagetown, and no one realized it had not been provided to Megan.

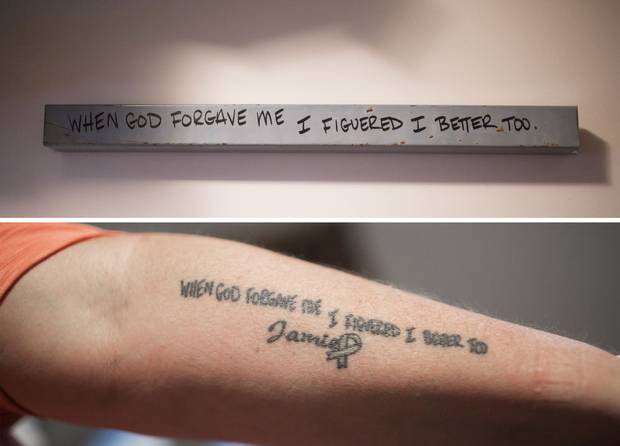

A while before his suicide, Cpl. McMullin had written these words on a grey metal strip in his basement: "When God forgave me I figured I better too." It's a near-quote from country-music legend Johnny Cash. The metal strip now hangs in his parents' front hallway. His mother has the words tattooed on her arm.

Top: Cpl. McMullin had written these words on a grey metal strip in his basement. Bottom: After his death, his mother had the words tattooed on her arm.

Michelle Siu for The Globe and Mail

Cpl. McMullin's parents believe the military's medical system failed their son. They say that not enough was done to treat him, to involve his family, or to keep him safe after his suicide attempt. After his death, they found enough unused pills to overfill a tin cookie can. "He fell through the cracks," his mother says.

The McMullins want the military and the federal government to commit more money, staff and programs to mental-health treatment.

Consider this small example of why they should: Gagetown's mental-health unit recommended to Cpl. McMullin that he read a particular book on PTSD, but the unit didn't stock any copies of it. He would have had to buy the book or sign it out from the public library – two things his father says his son would never have done because he didn't want to advertise his condition.

After Cpl. McMullin's death, his wife donated $5,000 to the mental-health unit so that it could buy PTSD-related books. The unit has a library now dedicated to her husband. Soldiers can simply sign out the book that Cpl. McMullin never got.

Sgt. Paul Martin with his wife, Hélène Bilodeau, and their daughters at an event recognizing the help that he offered to victims of a car accident.

Courtesy Martin family

Paul Martin, father of two. June 27, 1974 – Sept. 8, 2011

Sgt. Martin grew up in a blue-collar family in Bathurst, N.B. His father was a miner; his mother worked at a college cafeteria. He was 16 when he joined the reserves, transferring to the regular force at the age of 20. An infantry soldier, he embarked on his first overseas mission that year, deployed to war-torn Croatia as part of Canada's contribution to a United Nations peacekeeping force in 1993.

Hélène Bilodeau met Sgt. Martin after he returned from tour. He was a slim, dark-haired corporal, based in Valcartier, Que. A friend thought the pair would hit it off. But Ms. Bilodeau, a college student, was wary of army men because they spend so much time away. It didn't take long for Sgt. Martin to win her over. He was a good man and very funny. She liked that he was close with his family and that he wanted to settle down.

The couple married in 1997 at a small Quebec City chapel, not long after Sgt. Martin returned from his second overseas tour, this time in volatile Bosnia. When he deployed to Afghanistan in September, 2008, on the same tour as Cpl. McMullin, Sgt. Martin had already served in four foreign operations. The Afghanistan assignment worried Ms. Bilodeau. The peacekeeping missions had taken a toll on her husband, leaving him, at times, unable to sleep.

On the day he left for Kandahar, the couple gathered at the Gagetown base with other departing soldiers and their families. Ms. Bilodeau did what she had done many times before – kissed her husband goodbye, wished him good luck, and told him to be careful. Élody and Cloé, their two blond-haired little girls, were by their side.

Seven months later, her husband returned home a different man. A bomb had exploded near him in Afghanistan, causing temporary hearing loss and constant headaches. He was extremely nervous, jumping at loud noises. He was also quick to lose his temper, and his sleeping troubles worsened. Ms. Bilodeau would find him awake in the middle of the night, standing frozen in the basement. He seemed lost.

Two days after his return, Ms. Bilodeau urged her husband to get help. "You have to go to the emergency tomorrow because you're not my husband any more," she recalls telling him.

We are at her kitchen table having decaf coffee in Geary, a little more than 20 kilometres from the home of Darrell and Brenda McMullin. Her daughters are watching TV in the family room. Sharing this story isn't easy for her; her husband was a private man.

Sgt. Martin told his wife little about his experiences in Afghanistan, and Ms. Bilodeau didn't press him. This wasn't unusual. The brute rawness of war is hard to explain to those who weren't there to experience it. He did tell her a bit about the young soldiers under his command and the guilt he felt after he was injured in February, 2009, sidelining him in the final two months of his tour. He mentioned that several soldiers died in an incident while he was recuperating. For some reason, Sgt. Martin believed he could have prevented those deaths.

"He said, 'That's my fault,'" recalls Ms. Bilodeau, a teacher's assistant. "He said, 'Well, if I'm on the patrol, this never [would] happen.' He was really, really mad."

Sgt. Martin heeded his wife's pleas and sought help. Diagnosed with PTSD, he began to see a psychologist and a psychiatrist regularly in June, and was placed on prescription drugs that began making a difference, Ms. Bilodeau says, in French-accented English. Her husband was calmer, less aggressive.

The military had revamped its health services and mental-health programs after deep budget cuts in the mid-1990s. The goal was to improve the quality of treatment and access to care. But both the federal government and the Canadian Forces' medical system failed to keep up with the volume of soldiers returning from Afghanistan with severe mental scars.

Nearly one-third of soldiers who served in Afghanistan sought mental-health services within about four years of their deployment, according to a National Defence study. The researchers examined the medical records of a random sample of 2,045 soldiers who had deployed to Afghanistan between 2001 and 2008. They found that 14 per cent had been diagnosed with an Afghanistan-related mental disorder – 8 per cent with PTSD, and 6 per cent with illnesses such as depression and anxiety. For those who were in combat-heavy zones, the prevalence of PTSD was 25 per cent.

The rise in PTSD and other mental illnesses, in turn, strained the military's medical staff. Wounded soldiers encountered a chronic shortage of mental-health workers and, sometimes, long waits for care.

The need to double the number of Canadian Forces' mental-health professionals was identified as early as 2002. Yet, despite long-standing government pledges to expand the military's mental-health work force to about 450, staffing levels hovered below 380 for a decade.

As of September, the Canadian Forces was still 35 mental-health clinicians short of its goal. Forces spokeswoman Ms. Lamirande says that recruiting and retaining mental-health staff is a challenge due to a high demand for their services across the country, and that the military is aggressively working to fill the vacancies. Meanwhile, there is little question that the need for mental-health workers has only risen: The 450 mark was set before Canada's Afghanistan role morphed into combat.

Throughout his PTSD treatment, Sgt. Martin maintained his long-time volunteer firefighting position in Oromocto. The job allowed him to continue to serve the community, even as his military role diminished. But he was assigned a career-limiting medical category and subsequently transferred out of the infantry and into the base's Joint Personnel Support Unit (JPSU) in February, 2011.

Sgt. Paul Martin was a long-time volunteer firefighter. The job allowed him to continue to serve the community, even as his military role diminished while he sought PTSD treatment.

Courtesy Martin family

Created in September, 2008, the unit was designed to help mentally and physically wounded soldiers heal, offering programs and administrative support to those deemed unable to fulfill their regular duties for at least six months. The unit was also supposed to help them return to their military careers, if possible, or train them for new civilian jobs and smooth their transition out of the Forces.

The JPSU, though, took wounded members away from their units and the soldiers they knew, and it had been underresourced for many years. In a review of the support-unit program in 2013, the National Defence ombudsman found that it didn't have enough staff and that existing employees lacked sufficient training to deal with ill soldiers. The ombudsman's investigation of the JPSU is continuing.

According to figures provided by the Canadian Forces, 1,614 military members posted to the JPSU had returned to military work between July, 2010 and January, 2015. That compares to 2,053 who had been released from the Forces between November, 2009 and this past January. Many of the discharged members were classified as no longer fit to deploy – and therefore in violation of the military's universality-of-service principle.

This is exactly what happened to Sgt. Martin.

After nearly two decades in the military, he was forced to start over. He tried retraining to become a civilian heavy-equipment operator, but it wasn't going well. His wife says he was also battling Veterans Affairs for full recognition of his PTSD and the disability benefits that would accompany such a diagnosis. The dispute with Veterans Affairs appears to stem from the fact that Sgt. Martin stopped taking his pills in the spring of 2011 because he was feeling better. He told his wife that his doctor approved of the move.

Ms. Bilodeau told her husband she didn't think stopping his meds was a good idea. Soon, she saw the effects. He couldn't sleep. He became aggressive and agitated. "I think it was too fast," she says. "He took a big handful of pills every night just before going to bed, and took pills in the morning and at the lunch. And then he stopped."

Eventually, Sgt. Martin went back to the doctor. He was given only one medication this time, an antidepressant. About two weeks later, on Sept. 7, 2011, the family was on its boat docked on the Oromocto River. Sgt. Martin wanted his wife and daughters to sleep over, but the girls had school the next day and Ms. Bilodeau had to work early. They went home and Sgt. Martin stayed.

Around 10:45 p.m., he left in a beige pickup truck and called 9-1-1 on his cellphone. He told the operator he was suicidal, according to a military report obtained by The Globe. The RCMP dispatcher tried to talk him out of taking his life, but at some point he hung up the phone, stopped the truck and shot himself with his hunting rifle. The RCMP found his body at 1:20 a.m. He was 37.

Sgt. Martin left his wife a handwritten goodbye note. In it, he expressed his love for her and their daughters and his anger with authorities. He felt as if the army didn't want him and that Veterans Affairs didn't care. He was also worried about the family's finances.

Hélène Bilodeau with her daughters Cloé, left, and Élody at their home in Geary, N.B. Her husband, Sgt. Paul Martin, died by suicide in September, 2011.

Michelle Siu for The Globe and Mail

But there was much he didn't tell her. For instance, she didn't know that he had been golfing with Cpl. McMullin the day the young soldier killed himself three months before Sgt. Martin's death. She found out when I told her.

Neither she nor the McMullins know whether the pair was close, or what to make of the timing of their deaths. Sgt. Martin never spoke to his wife about the corporal or his suicide. The McMullins heard about their golfing day through a military friend of their son, who was with them on the course.

The tragic deaths of Cpl. McMullin and Sgt. Martin were not anomalies in 2011: Ten other soldiers took their lives that year after returning from Afghanistan. It is the highest single-year total since the beginning of the war. In all, 25 soldiers died by suicide in 2011. The number of vets who took their lives that year is unknown.

A military board of inquiry was completed in Sgt. Martin's death. A four-page executive summary and two-page letter signed by JPSU head Colonel Gérard Blais in March, 2014, was provided to Ms. Bilodeau. The military did not give her the entire report because rules in place at the time the inquiry launched, in 2012, didn't require that. That policy has since changed, and full reports are provided to families, although some details are redacted, says Ms. Lamirande of the Canadian Forces.

The Globe requested the inquiry report under the Access to Information Act. The 265-page document that the newspaper received in July was heavily censored. Even the recommendations were not decipherable, given the many redactions. The Globe learned of them through the short report provided to Ms. Bilodeau.

The executive summary in Sgt. Martin's death fills in some holes. It states that he showed signs of PTSD three times during his career, most significantly after returning from Afghanistan in 2009. He was deemed successfully treated in March, 2011, but that didn't change his medical classification or his posting to the support unit, "which he viewed as a stab in the back," the summary notes. The JPSU placement "left him feeling abandoned by his home unit."

The military reviewed Sgt. Martin's case, but his fate remained unchanged. He was scheduled to be medically released on Jan. 21, 2012.

"Sgt. Martin had spent his entire adult life in the infantry and was not ready for release," the board of inquiry's summary states. He strongly identified with the Canadian Forces, the report adds. "Sgt. Martin was not emotionally ready to leave the CF."

The board concluded that his suicide was attributable to his military service. It noted that Sgt. Martin experienced several traumatic events in his career that caused nightmares, insomnia, hyper-vigilance, irritability and an increase in his drinking. It also said he was not pleased with the outcome of his disability claim with Veterans Affairs.

On the night of his suicide, the summary says, he told the 9-1-1 dispatcher that he was in this situation "because he signed up for the army and that it was all he knew."

The board made four recommendations. It proposed assigning JPSU-posted soldiers an assisting officer from their home unit to maintain contact and to help prevent feelings of isolation. It recommended that medical staff involve family members in the soldier's treatment, to ensure that all concerns are identified. It proposed that soldiers slated for medical release be assigned a mental-health team to help prepare the soldier for transition to civilian life and to identify possible suicide risk. The board also urged the Canadian Forces to formalize a debriefing process after critical incidents to help prevent "mass mental-health casualties."

The board of inquiry's findings in Sgt. Martin's death have never been publicly revealed: Inquiry conclusions and recommendations rarely become public.

In the end, none of the board's recommendations was supported by military brass. In his letter to Ms. Bilodeau, Col. Blais said that improvements had already been made to the JPSU and that there weren't enough resources to assign a mental-health team to follow soldiers designated for medical release. Doing so, he said, would compromise the care of other members. The recommendation for formalized critical-incident debriefings was rejected outright. The reason given: There was not enough evidence in the medical literature to support the proposal.

Ms. Bilodeau has never read the inquiry's findings. Poring through the details would be too emotionally difficult, she says. The inquiry report went to General Tom Lawson, then chief of the defence staff. In a letter obtained by The Globe, Gen. Lawson said he agreed with Col. Blais, and did not support the board's recommendations.

Retired Sgt. Ron Anderson with his four children. The picture was taken on the first day of school in September, 2013.

Courtesy Anderson family

Ron Anderson, father of four. May 27, 1974 – Feb. 24, 2014

The military was the only way of life that Sgt. Anderson really knew. His father, Peter Anderson, spent three decades in the infantry, deploying twice to Cyprus and once each to Norway, Denmark and Germany, where Ron was born. A rambunctious child, he became a cadet at age 12 and enlisted in the regular force right after high school.

His father was happy for him. The military had provided Mr. Anderson and his family with a good life. He hoped it would do the same for his two sons. Ryan, five years younger than Ron, followed him into the infantry.

A father of four, Ron Anderson completed six overseas tours before he deployed to Afghanistan for the second time in January, 2007. He had been to Bosnia twice and to Croatia, Kosovo and Haiti. He was in Afghanistan in the early 2000s, when Canadian troops were largely based in less-treacherous Kabul, the capital. He received a commendation from General Rick Hillier, then chief of the defence staff, for providing first aid to an injured Afghan child struck by a non-military vehicle. A potentially dangerous crowd had formed, but Sgt. Anderson, then a master corporal, kept attending to the boy's wounds.

In the war-stretched army, Sgt. Anderson was prized: He was a well-tested soldier. But he was showing signs of PTSD before his 2007 return to Afghanistan. He should never have gone back, his parents say.

Sgt. Ron Anderson served for two decades in the army. He completed seven overseas tours, including two tours in Afghanistan.

Courtesy Anderson family

"I could have stopped him. I could have called in there," his father says, seated at his kitchen table with his wife, Maureen, in their home in Lincoln, not far from the McMullins. "But then he'd hate me because his brother was going."

This was Ryan's first time in Afghanistan and his big brother wanted to be with him. They were in H Company together, though not in the same unit. Their Kandahar tour was a "nightmare," Mr. Anderson says. They spent their entire six-month stint on the front lines, getting fired upon and firing back.

Now-retired sergeant Blair Williams was there, on the same tour as the Anderson brothers. He says that Sgt. Anderson helped rescue him and his crew after their light-armoured vehicle was hit by a suicide bomber. The blast disabled the vehicle and the Taliban were coming to finish off the injured soldiers.

Sgt. Anderson and his group were right behind. They got out of their vehicle and fired on the insurgents – one of whom apparently had a hand grenade, Sgt. Williams says. Ten Canadians were rescued that day; four of them were so badly wounded – including Sgt. Williams – that they had to be medevaced to Kandahar Airfield base for treatment.

"He was an excellent soldier," says Sgt. Williams, who himself was diagnosed with PTSD after the tour. "He was smart at what he was doing. He was knowledgeable about his job. He took care of his men."

One of the deadliest days for Canadian soldiers in Afghanistan occurred during Sgt. Anderson's tour. He and his crew were behind an armoured vehicle that was struck by a roadside bomb on April 8, 2007. Six soldiers were killed that day, five from Gagetown and one from a Halifax-based reserve. All were his friends. Sgt. Anderson and his men had to gather their remains.

"He saw a lot of death and dying, and that really bothered him," his mother says, her eyes downcast. In front of her are pictures of her son and a framed case with his military medals.

After Sgt. Anderson returned home from Afghanistan in mid-August, 2007, his parents could see he was struggling with mental illness. He was drinking harder and was more withdrawn. There were moments he would be happy to see his parents, and other times he would turn his back on those he loved. "He wasn't himself," his mother says.

Sgt. Anderson sought help. He was diagnosed with chronic and severe PTSD and severe major depressive disorder, according to a psychological progress report in his New Brunswick provincial court file. Although he was found guilty in October, 2008, of uttering threats against his then-wife and her parents, the judge gave him a conditional discharge, noting PTSD had completely changed his life, affecting his work, finances and family. His marriage had also broken up. Sgt. Anderson had never been in trouble with the law before.

At his bail hearing in June, 2008, Sgt. Anderson sounded tired and agitated. The court provided The Globe with an audio recording of the proceedings. Sgt. Anderson told the judge he was taking eight pills a day and seeing a psychologist and a psychiatrist regularly. He was getting only about three hours of sleep. "I haven't been playing with my children. Say hello, that's about it," he told the court. "I haven't been a father – playing sports with them or going to their school things, nothing like that since I come home from Afghanistan. I can't help it," he added. "I just want to be left alone."

The Crown attorney asked Sgt. Anderson when he first realized he had been dramatically affected by his deployments. Sgt. Anderson remembered the exact date: June 13, 2007, when he had an anxiety attack in the Afghan desert. "My heart started beating fast. I started vibrating. I started sweating profusely," he told the court. "So I went to see the medic and he knew what it was. It was just after my buddies got blown up."

Sgt. Anderson was eventually transferred out of the infantry and into the JPSU. The support unit was supposed to help him get better, but his father believes it did more harm than good. There were limited programs, staff and resources. According to Sgt. Martin's board-of-inquiry report, JPSU-posted soldiers were only expected to call in once week and show up in person once a month.

During his stint with the support unit, Sgt. Anderson spent most of his time at home, his parents say. Their son also started playing slot machines. His father estimates he blew through $60,000 in two months on gambling and alcohol.

"They sent him home. This is their solution? Three years he spent drunk in the basement," his father says. His mother, a retired nurse, adds, "I think that's the worst thing they can do, send these guys home."

Infantry veteran Peter Anderson says his son, Ron, was showing signs of PTSD before his second tour in Afghanistan in 2007.

Michelle Siu for The Globe and Mail

Sgt. Anderson was medically released from the military in 2013, after serving for two decades. He wanted to get away from Gagetown, and moved to Miramichi in northern New Brunswick with his girlfriend and her son. He bought a two-bedroom house and seemed to be doing better. His ex-wife sent their four children to live with him in August. He quit drinking to look after them.

The Andersons have a framed picture of their son with his four kids, taken on the first day of school in September, 2013. The retired sergeant, in a blue-and-red checked shirt, has a big grin. His left arm is wrapped around his boys; his twin girls are in front. It's their last family portrait.

He was struggling financially to care for everyone, and falling deeper into debt. Unable to work because of his PTSD, he was reliant on his disability benefits and a pension from Veterans Affairs. Bankruptcy records show he owed $105,459 in November, 2013. He didn't tell his parents about his financial troubles.

That winter was rough, his mother says. The pipes in her son's home kept freezing and he had to haul in water from the river. Sgt. Anderson was stressed, but no one thought he was suicidal.

His girlfriend found him in their shed early on the morning of Feb. 24, 2014. He'd shot himself with his hunting rifle. He was 39. His mother says his autopsy report showed he had medical marijuana and prescription drugs for depression in his body, but no alcohol.

Because Sgt. Anderson was retired from the military, he's not technically part of the Canadian Forces' tally of soldiers who died by suicide after serving in Afghanistan. He is among the untold more – the veterans whose deaths are not regularly tracked by National Defence or Veterans Affairs.

No boards of inquiries or formal medical suicide reviews are done in veterans' deaths. Veterans Affairs has a suicide-prevention program, but the department does not track how many vets kill themselves each year. Veterans Affairs spokeswoman Janice Summerby notes that when soldiers leave the military, they begin receiving health care through the provincial medical system. "As such, Veterans Affairs Canada does not have jurisdiction to undertake reviews of veterans' suicides," she says.

The Andersons are worried about their youngest son. Ryan was blown out of the hatch of an armoured vehicle when a bomb exploded in Afghanistan. He has back problems and PTSD, and is receiving treatment. He took his brother's suicide hard, his parents say.

Sgt. Ron Anderson, left, with his brother, Ryan, and their parents, Peter and Maureen. Retired Sgt. Anderson died by suicide in February, 2014. His brother was released from the military in September and is being treated for PTSD.

Courtesy Anderson family

Ryan is reluctant to speak about his brother or what he is going through. He didn't stay for the interview the two times I visited his parents' blue-grey bungalow on land dotted with birch trees. After 17 years in the military, Sgt. Ryan Anderson, a married father of two, was medically released in September.

"That's my biggest worry," his mother says, in a hushed voice. "Will Ryan be okay?"

Cpl. Scott Smith with his youngest son, Ian, who was born just before Cpl. Smith departed for Afghanistan in March, 2012.

Courtesy Smith family

Scott Smith, father of two. Feb. 7, 1983 – Dec. 10, 2014

Cpl. Smith overcame a lot of hardship early in his life. He never knew his father. His mother died of cancer when he was 7, and the boy moved to Calgary from England to stay with an uncle. Within a year, he was on the move again, to his grandmother's in Victoria.

They grew close, but she didn't have many people to turn to for help with his care. When she was hospitalized with pneumonia, she had to leave her grandson with her apartment manager. The illness made her realize there would be no one to look after her grandson in the case of her death. She made a difficult decision, and put him up for adoption.

Scott – whose original surname was Wilkinson – bonded immediately with his adoptive parents, Connie and Bob Smith. The couple had been on the adoption list for a decade and were about to give up. Scott was 11 when he came into their lives. Their son was a witty charmer. He played soccer and rugby during high school and was an excellent swimmer.

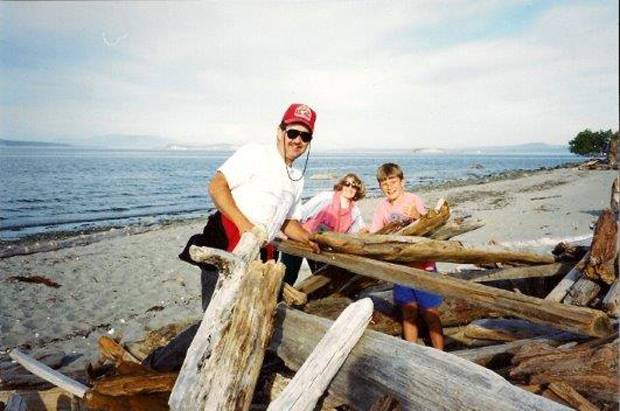

Scott Smith grew up on Vancouver Island with his adoptive parents, Bob and Connie Smith. This is the family’s first outing together, before the couple adopted him.

Courtesy Smith family

He was also very caring and wanted to make a difference. After high school, he began working with troubled teens at a wilderness boot camp on Vancouver Island. The job was challenging but rewarding. He went back to school to finish a certificate in counselling.

He was working for the wilderness camp when he met his wife, Leah, then 23. She had moved to the island's Campbell River from New Minas, N.S., in 2007. He was tall and muscular; she was petite and pretty. There was a spark between them.

The couple married a year later in a small ceremony at an inn by the Pacific Ocean. Ms. Smith had no inkling he was thinking of joining the army. He announced his decision to enlist a few months after their wedding. They were at a Tim Hortons, waiting to watch the Sex and the City movie. The film was his choice; in retrospect, she suspects he picked a chick flick to butter her up for the difficult news.

She remembers telling him: "As long as you're not front-line Afghanistan, I'm okay."

His parents, though, didn't think the military was a good fit for their son. He had experienced bouts of depression because of all the losses in his life, his mother says, and he sometimes drank heavily. Along with his biological mother's death, Cpl. Smith had lived through the death of his grandmother, from cancer, when he was 15. An Alberta uncle had died by suicide after losing his oil-patch job in the 1990s.

Connie Smith worried that the macho military culture would push her son to drink more, and that war would play havoc with his mind. "It was not an ideal environment for him," she says.

But military recruiters never called the Smiths for a reference or for insight into their son. After he enlisted, his mother says, she phoned his commanding officer and told him about her concerns. She called a second time after her son got involved in a drunken scuffle in a bar in London, Ont., where he and other soldiers were celebrating the completion of battle school, which followed basic training. She recalls a different commanding officer telling her he would keep an eye on her son.

Cpl. Smith and his wife were living on the other side of the country at that point, having moved to the Maritimes on New Year's Day in 2009. Soon after, Ms. Smith found out that she was pregnant with their first son, Casey – her husband had just left for basic training in St. Jean, Que. There was a lot of training. The couple spent more time apart during their marriage than they did together.

A second son, Ian, was born just before Cpl. Smith departed for Afghanistan in March, 2012. He was excited about his son's birth – but also about going on tour. "He didn't want to leave me and the boys, but it's something that is very good for their career," Ms. Smith says.

Although Canada's combat mission was over by the time Cpl. Smith deployed, a contingent of about a thousand Canadian troops remained to train and support Afghan security forces. There were still risks.

The Smiths communicated by e-mail, Facebook and Skype every other day during his nine months in Kabul. His enthusiasm for the tour diminished about midway through, Ms. Smith recalls. He was working long hours and was exhausted.

Cpl. Scott Smith on duty in Afghanistan in 2012. He was part of a contingent of Canadian troops based in Kabul, helping to train Afghan security forces.

Courtesy Smith family

When he returned from Afghanistan in November, Ms. Smith kept watch over her husband. She had spoken to other military wives and had attended a coffee-night chat at the Gagetown base, where family-support workers and a military chaplain walked families through what to expect when their soldiers returned. Ms. Smith looked for signs of mental trauma, but did not see anything immediately. While her husband had some trouble adjusting to day-to-day family life, he seemed to adapt.

The first really troubling sign emerged in October, 2013, after he'd been home for nearly a year. The Smiths were watching a movie, Pain & Gain, in their newly built home in Rusagonis, N.B., west of the Gagetown base. In the film, Mark Wahlberg and Dwayne Johnson play bodybuilders turned kidnappers and killers.

About midway through the movie, Ms. Smith says her husband zoned out and the colour drained from his face. He stretched out his arms, as if trying to grab at something. He started pacing and sweating. He was like this for two to three hours. Afterward, he tried to assure his wife he was fine. The scene that set him off was one in which the bodybuilders hit a man with a vehicle. Cpl. Smith told his wife it reminded him of an incident in Afghanistan.

After the movie meltdown, Cpl. Smith started to have more breakdowns and to distance himself from his family. The couple went to marriage counselling for more than a year, but in the summer of 2014, he decided he didn't want to continue with the sessions. He briefly sought help for alcohol use, but told his wife he didn't think much of the base's addictions counsellor.

When his parents came for a visit that fall, he refused to go to a pumpkin patch with them and his boys. He was withdrawn, his mother says. She got angry with him, unaware of his troubles.

About a week after his parents left, Cpl. Smith was alone, off-roading in his Jeep, when he thought he saw a suicide attempt in another vehicle. He didn't know whether it was real or a hallucination. Later, he told his wife and mother what happened. They tried to persuade him to seek treatment, but he was worried that doing so would scuttle his military ambitions. He was preparing for a leadership course and was up for a promotion – seeking PTSD treatment had cost others their careers.

"He was an extremely proud soldier," his wife says. "He really loved what he did. He had aspirations to go very high in the military."

Cpl. Smith was at a military Christmas party with his battalion on Dec. 10, 2014. It was part of a week of festivities at the base, and he came home from the party intoxicated. He and his wife quarrelled. That night was a breaking point for her. Their relationship was strained and Ms. Smith was worried about their boys. She told her husband she was going to leave him, and took off in her car.

He phoned her cell as she was driving, but she was not ready to talk. She didn't see his text messages until it was too late. The last one read: "I'm sorry this is how it ends. Tell the boys I love them."

Five-year-old Casey Smith hugs his blanket in front of a photo of his late father, Cpl. Scott Smith.

Michelle Siu for The Globe and Mail

Cpl. Smith was 31. His suicide was a shock to his wife and parents. When there had been a rash of military suicides the year before, Cpl. Smith told fellow soldiers to come to him if they were in trouble and uncomfortable talking with anyone else.

Both his wife and mother suspect Cpl. Smith had PTSD, and that the effects of his deployment to Afghanistan were a factor in his death. At the board of inquiry at Gagetown this past April, Leah Smith learned that her husband had slipped on ice and hit the back of his head at that Christmas party. She was told he was given first aid but didn't go to the hospital. She wonders whether the head injury played a role. The inquiry report is not yet complete.

It's unclear how much alcohol was in Cpl. Smith's body the day he died. For some reason, a toxicology test was never done.

His wife and mother want to see military culture change. They say seeking help shouldn't be viewed as a weakness and career killer by either soldiers or their commanders. His mother believes mental-health training should be ongoing, as integral to the military as physical fitness.

"If you can't actually see a wound, we as people, as a society, don't see it as them being sick," his mother says. "That has to change."

The Other Fallen, a painting created by several volunteer artists as part of Project Heroes, commemorates ‘those whose despair was so great they saw suicide as their only option.’ Project Heroes is a non-profit travelling exhibition dedicated to Canadian soldiers whose deaths are connected to the war in Afghanistan. The portrait in the upper left panel is of Cpl. Jamie McMullin.

The aftermath: More casualties to come

It's oddly quiet inside the New Brunswick Military History Museum at the Gagetown base. There is no one here to greet visitors, no one on this overcast day to trumpet Canada's hard-fought battles.

The museum isn't big. The siege of Fort La Tour during the Acadian civil war, the battle of Paardeberg in the Second Boer War, as well as the World Wars and other overseas operations are all depicted in one rectangular wood-floor room. But the statues of fresh-faced soldiers cradling assault rifles in unsullied uniforms don't truly capture the brutality of war – whether centuries ago or more recently.

The museum's exhibition ends in the mountains of Afghanistan, with two life-sized soldier replicas behind a thick mud wall. One is taking aim with his rifle; the other is taking cover.

The story of the Afghanistan war is still being written, here in Gagetown and at other military communities across the country. The military expects PTSD cases related to Afghanistan to keep rising until the end of the decade.

According to the Canadian Forces, in the case of many soldiers' suicides, there is no history of deployment. Between January, 2002, and April 8, 2014, 183 active-duty soldiers killed themselves; of those, 42 took their lives after serving in Afghanistan. Another two died by suicide in the mission, and possibly four others, although the Canadian Forces won't confirm the suspected suicides, citing privacy concerns.

Most of the families of the fallen Gagetown four have never met, but they are connected by grief. Their men were sent to fight on behalf of their country. They came home scarred, their way of life destroyed. The medical system that was supposed to heal them didn't. They didn't die in Afghanistan, but they are casualties of the war.

The families of Scott Smith, Jamie McMullin, Paul Martin and Ron Anderson told their stories in the hope they will help spur improvements in mental-health care, changes to military culture, and stronger support for those being released from the military. They want other soldiers who are struggling with mental trauma to get the right treatment. And they want the Canadian Forces to do more to help wounded soldiers return to their military careers. For those who want to stay in the service, PTSD, they say, shouldn't be a reason to expel them.

Sgt. Anderson's father pulls out his laptop to read a death notice just posted to the Royal Canadian Regiment's Facebook page. Another veteran had taken his life. The young man had two children and was engaged to be married. He served in Afghanistan in 2007, at the same time as Mr. Anderson's sons.

"Look at the suicides," Mr. Anderson says, jabbing a finger at the screen. "It's quite obvious what they are doing is not working. It's not getting better."

One veteran's road to

recovery

Retired master corporal Darrell McMullin was diagnosed with PTSD in 2004, but he didn’t seek help until after his son’s suicide in 2011.

Michelle Siu for The Globe and Mail

Retired master corporal Darrell McMullin struggled with mental trauma for a decade before he admitted to the army that he was ill. But he still didn't seek therapy for post-traumatic stress disorder, thinking he could handle his illness on his own as he retired from the military in 2004.

A mechanic who fixed battle tanks, he had deployed to war-torn Bosnia and Croatia during his two-decade career. The tours left him struggling with nightmares and getting little sleep. He seemed angry at everything and just miserable, his wife says.

His son's suicide in 2011 was a severe test to his fragile mental state. Corporal Jamie McMullin had followed his parents into the army. He was diagnosed with PTSD after serving in the Afghanistan war. After his son's death, Mr. McMullin's phone started ringing.

"I was getting calls from all these people and all his friends who were having the same struggles, and the first thing I would tell them is they needed to get help," he recalls. "One day I decided enough is enough. I needed to practise what I'm preaching."

Mr. McMullin called Veterans Affairs last year and told the federal department he needed help. He says he used to scoff at the idea of therapy. Now he's a believer. He takes anti-depressants as well as medication to help him sleep and to stop his nightmares. He sees a psychologist once a week. She has taught him how to cope with stress and how to look at situations in a different way. He gets about eight hours of rest a night and rarely has nightmares any more.

"I'm living life again," he says.

Where to get help

The Canadian Forces and Veterans Affairs have programs to help soldiers and their families who are struggling with mental-health concerns. They include:

- 24/7 member assistance program at 1-800-268-7708. The program provides telephone counselling for issues such as marriage trouble, depression, alcohol or drug abuse, and suicidal thoughts

- 24/7 family information line at 1-800-866-4546. The program offers telephone counselling to military families

- support from base chaplains

- crisis intervention through the veterans pastoral outreach program

- mental-health clinics and family resource centres at Canadian Forces bases and wings

- 1-844-236-8387 to reach the Veterans Transition Network, whose mission is to make sure no vet suffers in isolation

Renata D'Aliesio is a national news reporter with The Globe and Mail.

Are you a military family with a similar story? Email Renata D'Aliesio at rdaliesio@globeandmail.com as she continues to bring attention to this important issue.

Follow Renata D'Aliesio on Twitter: @RenataDAliesio

Send confidential information to Globe journalists using SecureDrop.

…