An Uber pulls up to a Weston Road plaza populated by no fewer than five Caribbean restaurants. Carrie Mullings gets in the car and says hello to the driver, a young black man. They make small talk, she jokes about how Jamaicans are always running late and the driver erupts in laughter, nodding vigorously in agreement. He drives a bit more. There's silence. Suddenly, the Jamaican accent Ms. Mullings had been masking bursts forth.

"So which parish yuh from?" she asks, locking eyes with the driver in the rear-view mirror. "Mmm?"

He tells her the name of the Jamaican parish he grew up in. Then asks her the same: "Where yuh from? Manchester, eh?" referring to Manchester Parish in central Jamaica.

She smirks. "Mi from Manchester? No sah. Mi bawn yah."

It's true: she was bawn yah (born here) in Toronto to a white Canadian mother and black Jamaican father. And like so many other second-generation immigrants with parents from the West Indies, especially the ones growing up in neighbourhoods such as Scarborough Rouge or the Jane-Finch corridor where Caribbean populations are concentrated, Ms. Mullings's speech is peppered with patois and delivered with a Jamaican accent.

In early 2015, just before he dropped his mixtape If You're Reading This It's Too Late, Drake released a short film, Jungle, in which he spoke with a faint Jamaican accent, mixing in a bit of patois, the distinctive vernacular of the country – a flavour that emerged on many tracks and came out even stronger in 2016's Views. Many listeners, particularly in the United States, were perplexed: Why was the rapper with an African-American father and Jewish-Canadian mother suddenly speaking in a way that suggested he was from the islands? Most living here, though, recognized the sound. It's just a GTA ting.

Caribbean culture has become so influential in the city that bits of the patois language and the accent that goes with it have filtered down to much of the rest of the population, including Drake, creating what both linguists and visitors to the city notice as a very distinctly suburban Toronto sound. South Asians in Mississauga respond to questions with ahlie as an affirmation or to state skepticism. Croatians in Malvern will say from time in reference to something that happened long ago. Somalis in Rexdale will greet each other with a wah gwan? rather than asking what's up.

English is Jamaica's official language, but patois (or Jamaican Creole as it's called by linguists) is widely spoken. It's its own distinct language, not just a dialect, and draws influence from English primarily but also Spanish and West African languages.

For some native speakers and their children, the popularization of their language stirs up complicated feelings. Some see this as a positive evolution: a sign of the reach of reggae and dance hall culture around the world. Others, meanwhile, complain it's used mockingly, or is just another example of appropriation – when outsiders adopt a language that has made its native speakers the targets of discrimination.

Generation gap

The lunch rush at the New Caribbean Queen Jerk Drum, a busy spot at Finch Avenue West and Weston Road, has died down and staff are now chatting with each other, stealing glances at their phones. Courtney Grant, the owner, emerges from the kitchen, his green t-shirt stained with a spot of sauce from the fiery curry goat he made. He sits down at a booth with his 17-year-old daughter, Shavoni.

The majority of customers on this weekday are black but the odd East Asian or white customer will come in for a takeaway container of jerk chicken or stewed oxtail. When asked what it's like to hear some of them drop patois in their speech, Mr. Grant smiles.

"It feels good," he says with an accent that's stayed with him since he moved here from Saint Thomas in the U.S. Virgin Islands.

His daughter holds up hand manicured in yellow and silver nail polish to his face as a gesture to stop.

"Why?!" she asks, horrified.

Mr. Grant explains that it shows their language is important. "Everybody wanna be associated with patois now," he says.

Ms. Grant, who speaks with an accent that doesn't betray her ethnicity, sighs.

The Caribbean diaspora in the city has slowly grown since immigration from the islands really took off in the 1960s. There are 627,590 people of Caribbean origin in Canada, and about half of them live in Toronto, according to the 2011 National Household Survey. Jamaicans make up by far the largest portion of the city's black population. But in those early days, being dark-skinned in old, white Toronto the Good was historically more of a liability than a marker of pop-culture cool.

Ms. Grant attends Vaughan Secondary School in Thornhill, where it’s become commonplace to hear groups of white girls trying out patois phrases when they converse. She credits Drake for the phenomenon.

Mark Blinch/The Globe and Mail

Ms. Grant's parents, as with many others, scolded her when she spoke patois at home.

"My family came from the ghetto to where they are now. They don't want me to look like the ghetto," she explains.

The Grants lives in Woodbridge now, but first settled in Chalkfarm, a Downsview neighbourhood that has long been associated with drugs and violence. After arriving in Canada, Mr. Grant learned quickly not to tell people which neighbourhood he lived in.

He cringes when he sees black kids get on a bus and start cursing, knowing that some of the non-black passengers will assume all black kids swear a lot. When he worked as a furniture delivery man, he'd sometimes show up to a job at a white person's home and as soon as they heard his accent, they'd mimic it.

"They will try to imitate the f-word. And then the next ting: 'Yuh got a ganja spliff, mon?' They think everybody smoke [marijuana]."

Ms. Grant attends Vaughan Secondary School in Thornhill, where it's become commonplace to hear groups of white girls trying out patois phrases when they converse. She credits Drake for the phenomenon.

"It's annoying. They don't really know what they're saying," she says. "They'll say, 'Oh, this guy's such a waste yute [useless person].' They overuse it to the point that I don't even want to use it any more."

Jafaikan

The most infamous local use of Jafaikan, as Londoners call it, was in 2014, when a video leaked of an intoxicated former Toronto Mayor Rob Ford sitting in a Rexdale fast-food restaurant, incoherently ranting about police surveilling him. He received heavy criticism for speaking in a Jamaican accent and using patois swear words – the kind that some musical performers have been fined for saying on stage in Jamaica.

"There is a legitimate fear by some Jamaicans that Jamaicans are already seen as aggressive, perhaps not willing to assimilate into Canadian culture," says Clive Forrester, who taught a York University course in Jamaican Creole. "Here's a person who is behaving in an unsavoury manner and using Jamaican language and more or less emboldening the critics of Jamaican identity and Jamaican culture."

In a video that surfaced in January 2014, former Toronto Mayor Rob Ford ranted about various things using Jamaican patois.

Fred Lum/The Globe and Mail

Mirna Eljazovic joins all those Jamaicans who were angered watching the late Mr. Ford's bumbling attempt at code-switching. She moved with her family from Bosnia to Hamilton in 1994 and since she was 13, patois has been a regular part of her vernacular.

She was one of the few white people in her predominantly Jamaican high school and today, at 30, her closest friends in Toronto, now her home, are black (from Africa and the West Indies) and her boyfriend is Jamaican.

She rolls her eyes at the lazy non-black patois speakers, the ones who say "Ya mon" or "Everyting is irie" with a cartoonish accent. That use of the language feels mocking or disrespectful, she says.

Meanwhile, dropping eediat (idiot) or cyattie (an undesirable, high-drama woman) in her speech has never felt like a performance or disrespectful for Ms. Eljazovic. These terms populate her vocabulary and flow from her mouth as easily as the Canadian English ones do because they're ones she grew up hearing and saying.

"It's like when you start speaking to your friends, it's a mutual language that we all use," she says.

History of patois

Things were very different just two decades before Ms. Eljazovic was dishing with her Caribbean friends.

When Ms. Mullings, the Uber passenger, was going to school in the late seventies, her Italian friends would speak it with her – but clandestinely. "Their parents hated it. It would be something you hide. Like how you put your miniskirt in your backpack and put it on at school."

Because the West Indian influence on language in the GTA is relatively recent, few studies on its evolution exist. But London has seen a parallel phenomenon, which can provide clues to the development of our homegrown lingo.

Linguists have extensively studied the settlement of Jamaicans in the British capital and the influence their culture and language has had in their new home. West Indian immigrants arrived there a decade earlier than they did in Toronto but, so far, many of the same patterns in the evolution of the language can be seen here, too, says Lars Hinrichs, a linguist at the University of Texas at Austin who studied the role of patois in Toronto a few years ago.

In London, it was only the first wave of immigrants in the 1950s and 1960s who spoke patois. In the 1970s and 1980s, the next generation, their born-in-Britain children, were the code-switchers, alternating between London English and patois. At this point, second-generation West Indians from other countries also began lacing their speech with patois, and black youth from Africa as well – it was no longer a Jamaican language, but a black language. By the 1990s, white, British-born youth were speaking confidently in a mix of English and patois. Most recently, linguists have seen the emergence of a new dialect: Multicultural London English, which is widely spoken by the young working class, regardless of ethnicity.

A pair of Canadian researchers have studied what they call Black English in Toronto, which is characterized by a faint accent and high levels of what linguists call t/d-deletion – dropping the final T or D in a word, as in "I can' wai' to go there" or "She pass' her exam yesterday."

"It's not something they seem to turn off or on, so I wouldn't call it code switching," says Jacqueline Peters, an adjunct professor of linguistics at Concordia University and one of the study's authors. "I don't even know how many of them would be able to speak what we call 'standard' English."

Over the airwaves

Ms. Mullings gets irritated when people dismiss patois as the language of uneducated people, or say it's just broken English. Her late father Karl Mullings, a co-founder of Caribana and major booster of Canadian reggae music, taught her patois at home and stressed it was an important part of her Jamaican culture.

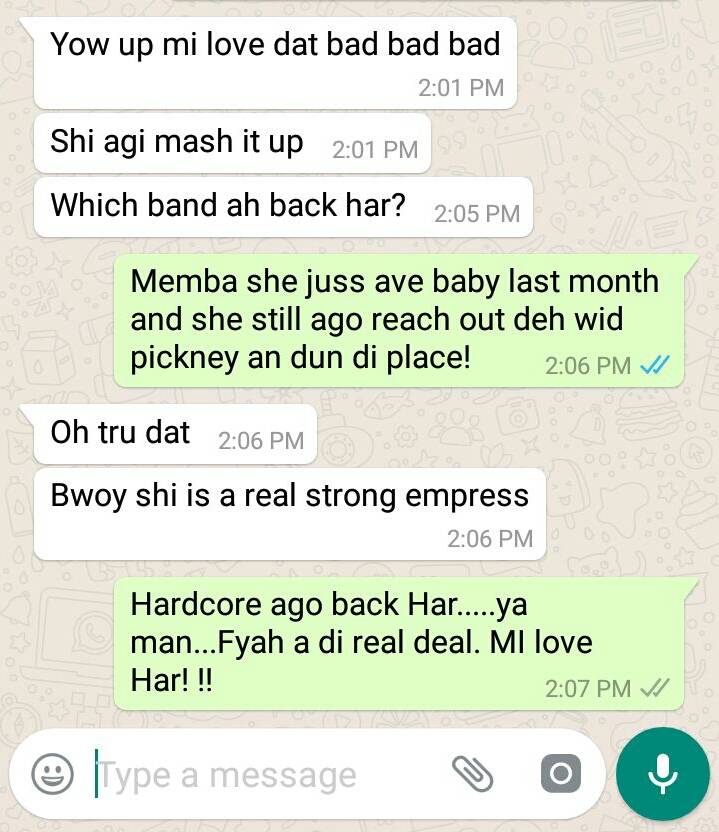

Ms. Mullings's life now revolves around that scene: she helps organize reggae festivals, hosts the reggae show Rebel Vibez on the radio station VIBE105, and manages many reggae artists around the world, including some who are white.

In the radio studio, she switches seamlessly between heavy patois when she does catch-up calls during commercial breaks with the Jamaican singers she manages and then English rounded out with a voluptuous Jamaican accent when she's on air. She wants to speak to her Caribbean base, but also make the show as accessible as possible to all Torontonians, of any race.

Last Monday, while playing one reggae song, a listener sent her a WhatsApp message, requesting that very song. Ms. Mullings programmed it in again and got on the microphone.

"Mi bran new favrite. Wanna say gud mawnin to Ms. Amber Hardy who's lissening in on the outside. I hope yuh feelin betta, sis. Naw gon play dat one ya back for you. Just for you. Oh Na Na Na," she said, and the reggae beat rose.