For the 905, a region known for sprawl and environmental apathy, the Places to Grow Act was passed with the hopes of trading up for urban density and Greenbelt protection. Ten years later, Dakshana Bascaramurty assesses the progress of two municipalities facing sky-high expectations

It was heralded as one of North America’s most progressive growth plans: a piece of legislation that pledged to populate the Greater Golden Horseshoe with live/work neighbourhoods, protect the Greenbelt and bring an end to the 905 region’s reputation for sprawl. The Places to Grow Act promised to bring density to all of Southern Ontario – not just more condos in downtown Toronto, but townhouses, low-rise apartments and narrower lots – because sticking with the status quo was simply too costly.

“We know it’s too expensive to grow out and we need to start growing up to save our tax dollars, to save our health and to improve our quality of life in urban centres,” says Susan Swail, the Greenbelt Project manager at the NGO Environmental Defence.

But a decade since it was passed, has Places to Grow stayed on track to transform Ontario’s suburban outposts into models of urban efficiency that both attract new residents and generate employment? In a region where the population is expected to swell to 11.5 million by 2031, the stakes are high.

The planners who have had to translate these guidelines to local contexts have faced challenges from all directions: a lack of market demand for high-density living, resistance from long-term residents and infrastructure gaps. And even those who have figured out how to draw new residents have struggled with generating jobs for them.

The Globe and Mail stopped into Oshawa and Milton, the municipalities at the eastern and western edges of the GTA, to discuss smart growth – and the obstacles to achieving it – with planners, politicians and residents.

MILTON

At the time Places to Grow was passed, Milton had a population of 56,000. That figure has since doubled and it’s expected to hit 230,000 by 2031.

The Good So Far

The desire for a home to raise a family and a better connection with the outdoors was what drove Alex Kjorven and her husband, Austin, from a condominium in downtown Toronto to a much roomier two-storey detached house in north Milton last September.

Even after the move to Milton, the Kjorvens have kept their jobs in Toronto – as well as their progressive ideas about density. There are signs that some of that is slowly catching on in the town they now call home.

Milton’s planning team has tried to encourage more height through zoning and promoting alternative medium-density housing, such as back-to-back townhomes. New construction in this form can reach densities of up to 100 units per hectare, says Gabe Charles, senior manager of planning policy and urban design. They’re attractive to builders because they can be cheaper and easier to manage than a four-storey condominium.

One such promising neighbourhood is in southwest Milton, near Dymott Avenue and Tremaine Road. While laid out like a traditional subdivision, it’s filled with three-storey townhouses, units, narrow lots and a bike lane.

The Bad

In the few months Ms. Kjorven has spent in Milton, she has noticed that many of her neighbours – the so-called “Old Milton” crowd – are resistant to new development in the town.

“I don’t know if I can bring my progressive, youthful optimism into the conversation,” she says. “I’m disappointed that so much of the discussion around [new developments] has been really negative messaging.”

When Places to Grow targets are mentioned at public consultations, residents often ask, “Why can’t you tell the province ‘no?’” says Bronwyn Parker, a senior policy planner with the town. One promising proposal for a 151-townhouse complex in the city’s core is an “appropriate density” for the area, Ms. Parker says, but a group of about 50 residents has protested it, saying it is too dense and too tall.

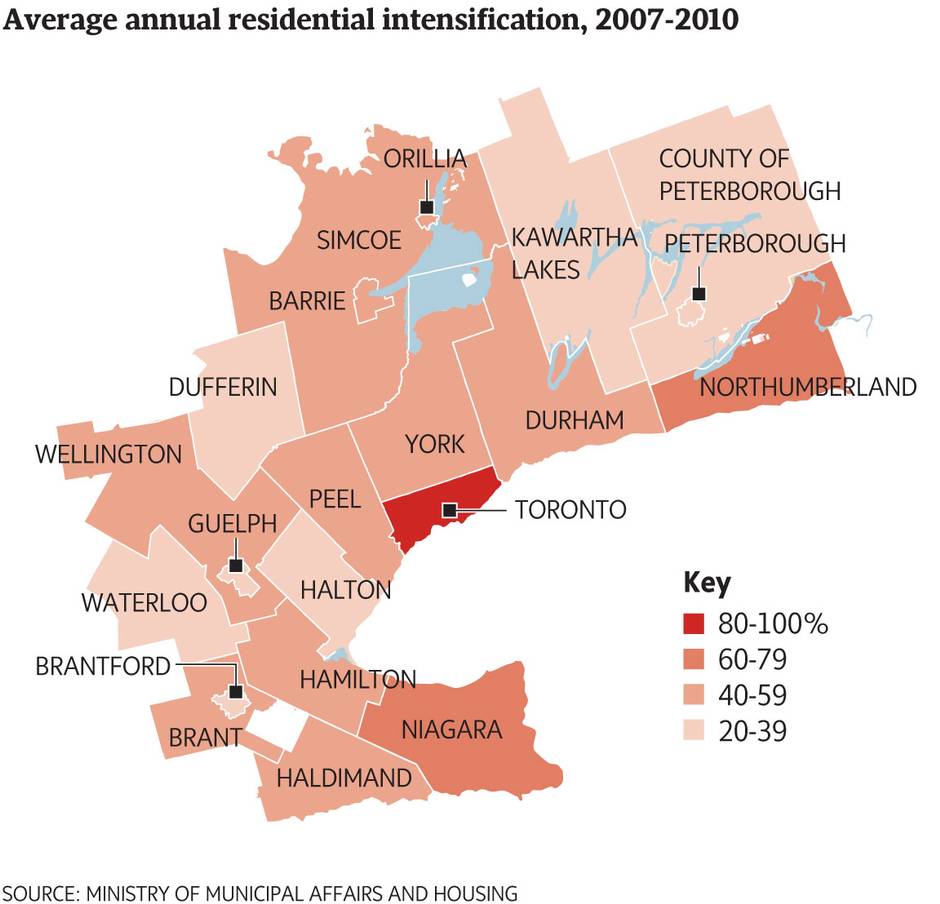

Places to Grow requires that by 2015, at least 40 per cent of annual residential development must happen within a municipality’s existing boundaries. Most are meeting that target based on provincial data from 2007 to 2010, but Halton Region (where Milton is located) lags the others at only 33 per cent.

Milton’s bigger struggle is with meeting the job targets of Places to Grow. More than most other GTA suburbs, it’s still a bedroom community; it isn’t attracting the same high-tech companies as Markham, and unlike Mississauga and Brampton, isn’t conveniently located near the airport. Planners emphasize the importance of building jobs around transit hubs, but little development has happened around the Milton GO station. Ms. Kjorven is at the station each weekday – but it’s to take the train to Toronto, where she and her husband still work. For now, the jobs they want aren’t available in their town.

The Canadian National Railway threw a monkey wrench into the town planning process when it made the recent announcement that it will build an intermodal station on land it owns in the town’s southwest end (a move that has been protested widely by politicians and residents due to environmental and traffic concerns). Before CN’s announcement, the town had planned to turn the area into employment lands to meet Places to Grow targets of 50 jobs per hectare. If the plan for the facility goes through, the pressure to meet those targets will have to be shifted elsewhere in town, Mr. Charles says.

“Where do we replace that? How do we replace that?” Mr. Charles says. “To say it caught us off guard is an understatement.”

The Road Ahead

The way residential housing is shifting in Milton is a promising sign, but it doesn’t seem to be changing as dramatically as it needs to. Milton is still seen as “the last best west” for GTA residents seeking affordable detached homes, and as long as that reputation remains, it will be difficult to get developers on board to build more progressive housing.

When it comes to density in downtown Milton, which is supposed to hit 200 people and jobs per hectare by 2031, the town is still lagging far behind most others in the region. In 2011, the most recent year measured, the density was only at 34.4 people and jobs per hectare, according to the province’s survey of progress, released in March. Milton has big plans for a satellite campus of Waterloo’s Wilfrid Laurier University, near the newly constructed Milton Velodrome, but the province has not approved those plans yet. If they go through, the area, known as the Milton Education Village, could help the town finally grow beyond its bedroom-community status.

OSHAWA

In 2005, Oshawa’s population sat at 146,795 and at last count was at 156,701. It’s expected to swell to 197,000 by 2031.

The Good So Far

When Dave McMillan, a tool and die maker, first moved to Oshawa two decades ago, he saw it merely as a “dirty town,” its dingy core surrounded by characterless sprawl. But in the past five years, he’s seen a substantial transformation in the city, prompted in part by its need to rise from the ashes of a partly collapsed automotive sector. Now, Mr. McMillan sees promise in the downtown revitalization and north-end development, so much, in fact, that he finally bought a house in Oshawa last summer, despite working in Brampton.

Mayor John Henry says the construction of the University of Ontario Institute of Technology in the north end and the residential development it has spurred along Simcoe Street North has been the most progressive growth the city has seen in the past decade.

The street, which was once just a wide expanse of rural land, has now become home to thousands of students who attend the University of Ontario Institute of Technology and Durham College. Several rental buildings have cropped up along the corridor and more are under construction. “[The north end] has developed nicely. It’s new, it’s fresh, it has brought a lot of people to the city,” Mr. McMillan says.

The Bad

In Mr. McMillan’s view, the only downside to the building boom in Oshawa is that Taunton Road, a major east-west thoroughfare, hasn’t been expanded to keep pace with the increased traffic.

The added pressure for infrastructure improvements is top of mind for the city’s planning department, too. The team has big plans for creating employment areas around the campus, but ironically cannot move forward to meet the province’s job creation targets without increased funding from that same level of government to put in water and sanitary services, says Paul Ralph, the city’s planning director.

“You can have the best planning documents in the world … but we need help on the infrastructure side from the province,” he said. For decades, local politicians in Durham Region asked the province for funding to extend Highway 407 further east – expansion was seen as a key factor in attracting businesses. After a series of delays, construction is now under way. Mr. Henry says many of his calls to the ministries of environment and municipal affairs are often passed down a long chain and ultimately yield no action or funding. But the province is making efforts: In late March, the Premier met with nearly every mayor in the GTHA in what she promises will be twice-yearly summits.

U.S. cities such as San Francisco and Portland, Ore., have had the most success with targeted job growth, says Melanie Hare, a partner at the planning firm Urban Strategies who helped put together parts of Places to Grow. That’s because they understand that infrastructure improvements must happen in the same areas a city wants to see increased density, she says.

“It’s a huge lever to try to encourage that employment growth in the right place.”

The Road Ahead

In Oshawa, mid- to high-rise construction has been limited mostly to rental towers geared toward seniors and students; drumming up interest in condominium ownership has been tougher for the blue-collar city. The growth of this form of housing depends largely on an aging population choosing to stay in town and downsize. Right across the region, the mix of housing stock is changing, but not dramatically: While 54 per cent of the new housing units built in 2006 in the GTA (excluding Toronto) were single detached homes, by 2013, it was down to 47 per cent – the share of apartments and row houses grew in that period.

Like Milton, downtown Oshawa was assigned a targeted density of 200 jobs and people per hectare by 2031, and based on provincial indicators, it’s halfway to that goal. While many of its neighbours have struggled with creating jobs, Oshawa, while still far from its target, is making great strides thanks to a recent boom of infill construction of new warehouses and plants downtown. Last year, the city set a development record by issuing more than $500-million worth of building permits and expects construction from all those approvals to hum along for another decade. With the right investment for infrastructure improvement, the city stands a good shot of not just reinventing its economy, but also attracting new workers and residents. Many who have studied development in the greenbelt, such as Ms. Swail and Ms. Hare, say the single greatest determinant of success for these sprawling communities is better transit infrastructure – finding a way to connect new residents to jobs without the reliance on cars.

Even with a ways to go before meeting their targets, Larry Clay, the province’s assistant deputy minister of municipal affairs and housing who has been monitoring the success of Places to Grow, says he’s not concerned about the slow start some municipalities have had. He points out that many didn’t get their official plans updated until years after the act was passed, which means they’re only a few years in to this new era in planning. “We’re projecting over the long term,” he says. “The economy has ups and downs over [the last decade]. There’s a lot of confidence that those forecasts will be accurate and will be met.”