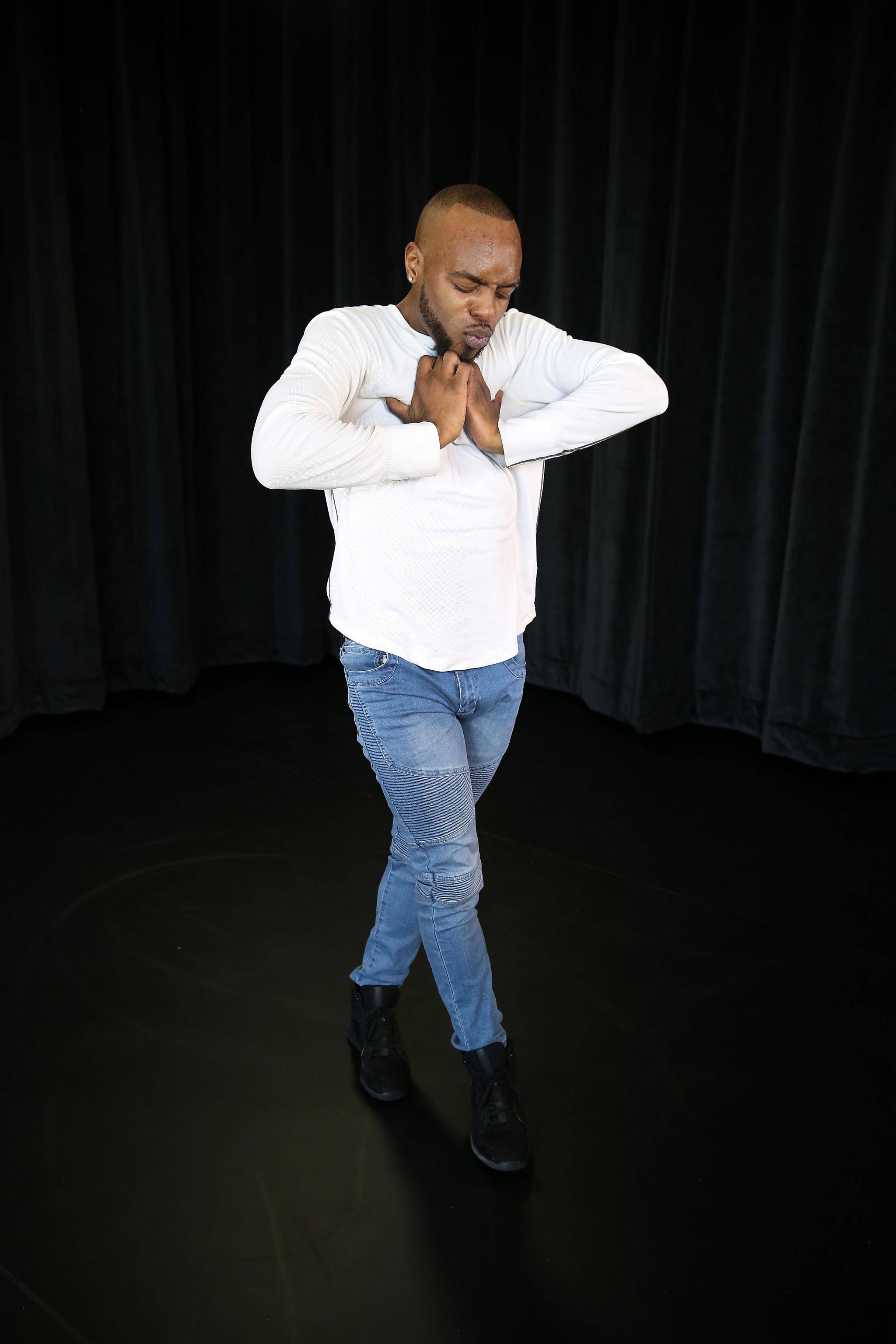

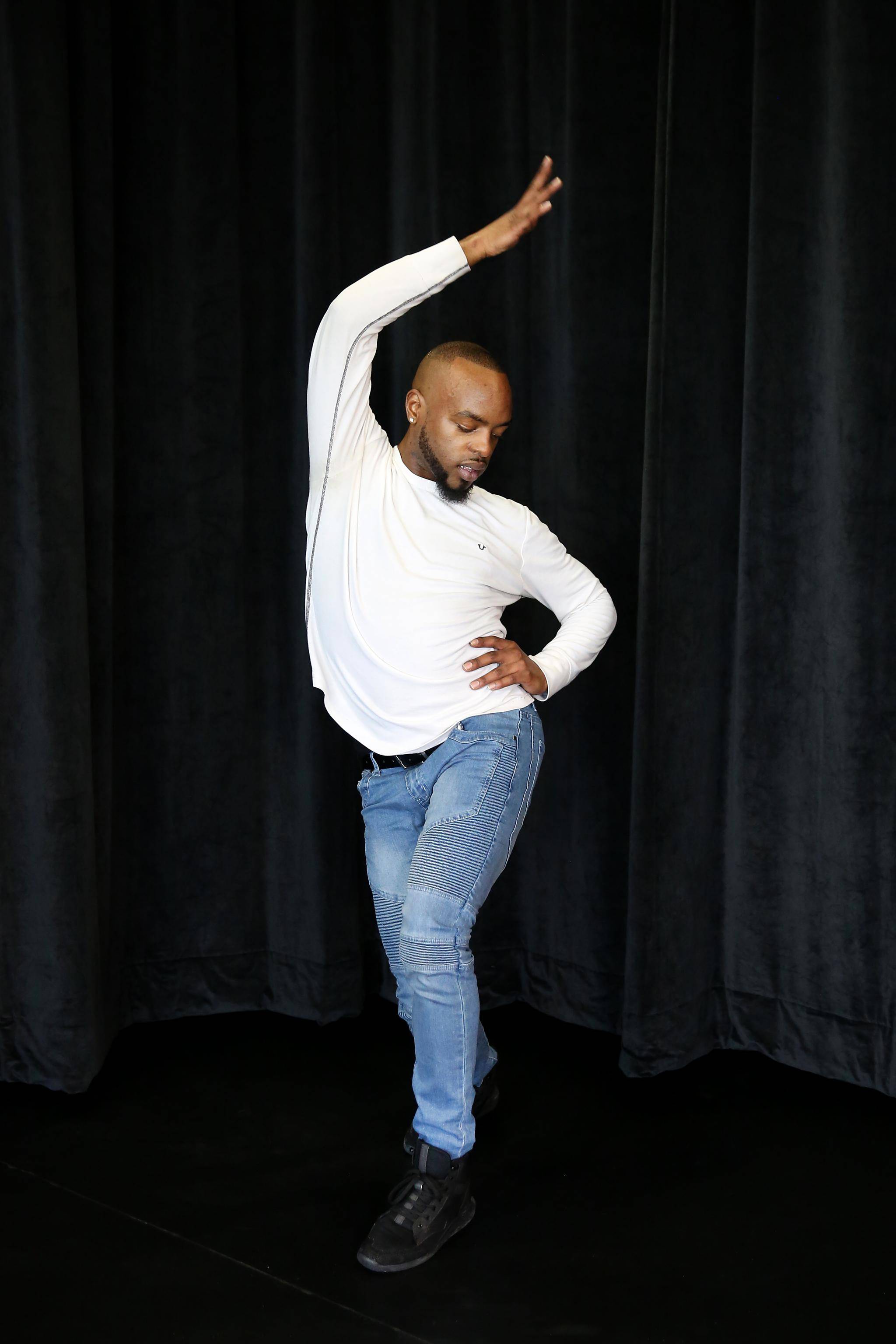

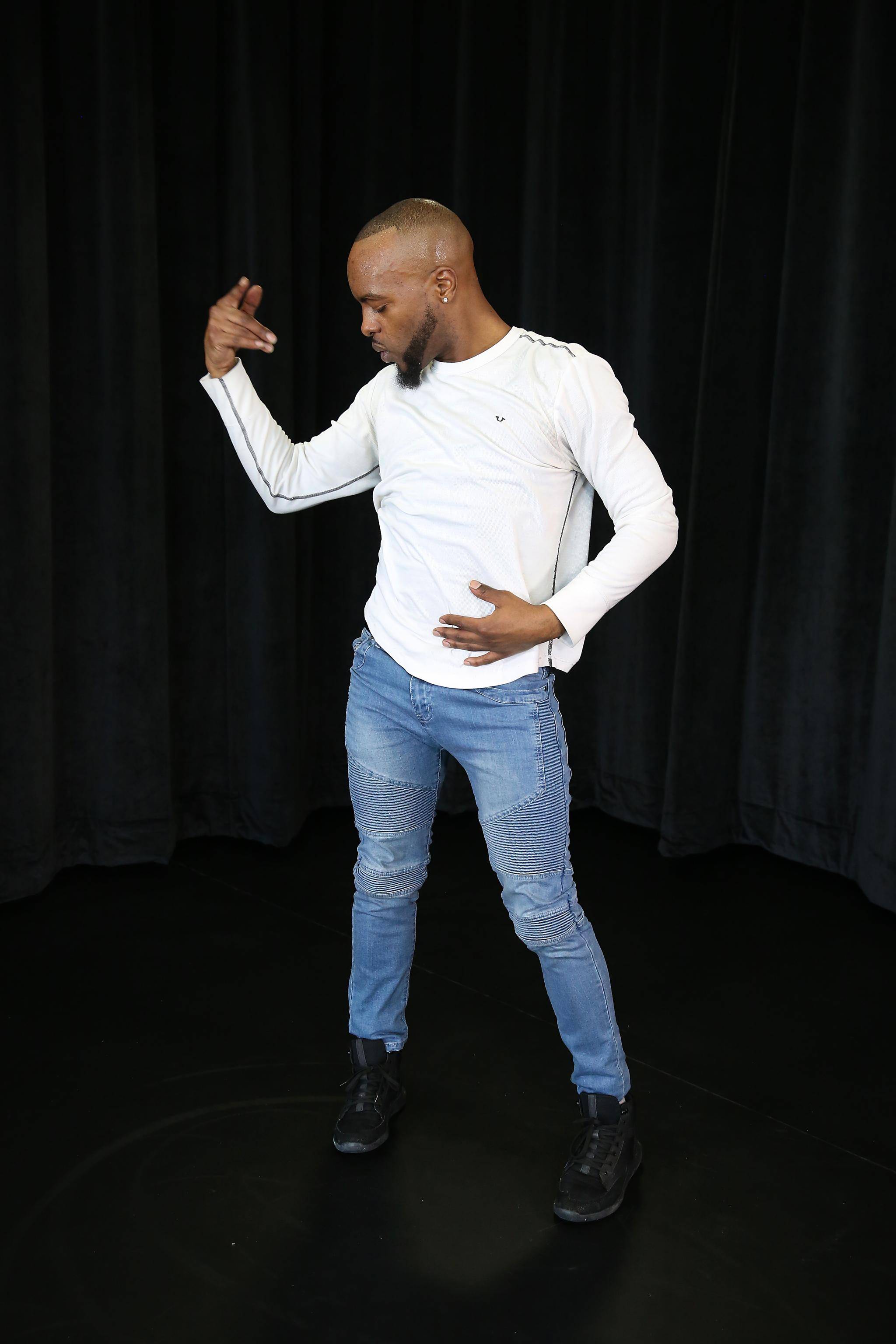

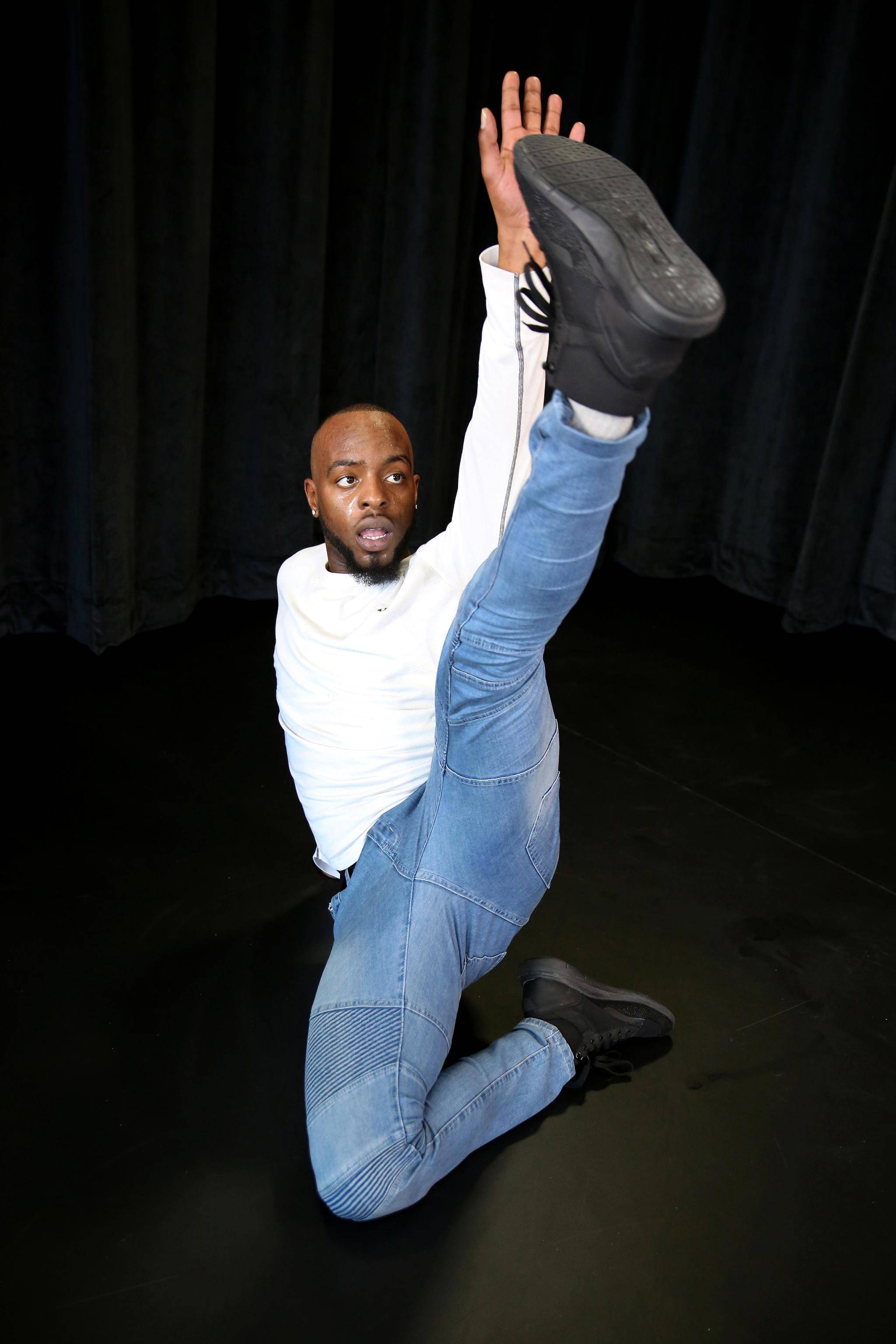

As he vogues, it's clear that Twysted Miyake-Mugler is a lifelong athlete. He has the stamina to duckwalk, a dance done while squatting. He's flexible enough to do the splits, and strong enough to pull himself back up to a standing position after dropping dramatically backward to the floor – on beat, of course.

It's not surprising that he used to be a hip-hop battle dancer, or that he ran track and played football throughout high school. But what gave the 29-year-old his initial love of movement was gymnastics, as a child.

"My mom took me out of that when I was six or seven," says Mr. Miyake-Mugler, about why he stopped. "She said it was too feminine."

Twysted Miyake-Mugler, Co-founder of the Toronto Kiki Ballroom Alliance, vogues

He plans to have his whole self on show at Toronto's first Black Liberation Ball on Saturday, Feb. 10. The much-anticipated dance competition and party is at Harbourfront, and ticket sales are brisk.

"It's going to be hot," says Mr. Miyake-Mugler, who is a co-curator of the event. He'll do live commentary as competitors add individual touches to moves that gay black and Latino men and transgender people have been doing for decades.

It's fitting that the ball is taking place during the 23 rd annual Kuumba festival. Harbourfront was Toronto's first major arts organization to mark Black History Month, and over the years the event has grown increasingly political.

That often means more complicated, too. Much of this year's programming aims to untangle how black identity intersects with other aspects of people's lives, including being LGBTQ.

Mr. Miyake-Mugler's ties to Harbourfront come through Brandon Hay, founder of the 11-year-old Black Daddies Club. Known as a passionate advocate for Toronto's black families, Mr. Hay's work challenging stereotypes about black men drew him into challenging homophobia, too.

Mr. Hay recalls a conversation with a Black Daddies Club member who felt ostracized from both white gay men and the straight black community.

"Here is this dude who is, like, living on this double-edged sword kind of vibe, like, who does he call community?" says Mr. Hay, who has three sons.

"Me, as a black man, I recognize what oppression is, so I'm not about the idea of oppressing another community, especially someone from within my own community. It just seems backwards, you know?"

So when Harbourfront approached Mr. Hay to curate a Kuumba program, he knew that he needed a co-curator who was black and gay. He reached out to Mr. Miyake-Mugler, as well as New York-based ballroom dancer and academic Michael Roberson, both of whom he had met a few times earlier.

Mr. Miyake-Mugler also has plenty of experience discussing difficult topics with marginalized people. His day job is with the Black Coalition for AIDS Prevention, and he's a co-founder of the Toronto Kiki Ballroom Alliance, which teaches youth how to vogue in an alcohol-free environment.

"It's so they don't have to sneak into the clubs like we used to," he explains. "We were put into adult situations at a very young age."

As a teenager growing up at Jane Street and Finch Street West in the mid-1990s, Mr. Miyake-Mugler would often head downtown to Church Street so that he could "be myself, even if only for one night a week." He was dancing hip hop and dancehall reggae, but in the wee hours, DJs would switch to house music and the few who knew how to vogue would take the floor.

Mr. Miyake-Mugler tried out a few experimental moves and developed a vogue obsession, as well as an appreciation for history. "I had no idea that house music had its origins in black gay communities," he says. "I thought it was white music."

Ball culture dates back to at least the 1960s, while house music and voguing were born in the same era as hip hop and breakdancing. But an association with gay men, drag queens and transgender people pushed voguing and its community out of the spotlight after Madonna's chart-topping 1990 single.

A vogue resurgence is well under way. Top performers compete with ballroom "houses" and, four years ago, Mr. Miyake-Mugler was drafted by New York's influential House of Miyake-Mugler (hence his stage name).

That doesn't mean homophobia has necessarily lessened, and Mr. Miyake-Mugler often feels excluded, if not targeted. "Even the more progressive people and their more progressed ways of homophobia…they're like, 'You guys stay in your lane, and we stay in our lane,'" he said. "There's never no crossing of lanes."

That's exactly Mr. Hay's goal. "A lot of the conversations about liberation and oppression so forth in the black communities, these are not new conversations," he said. "What I saw there was a gap or an opportunity for… starting to have these cross-border conversations."

The product of their efforts is the weekend-long Journey to Black Liberation Symposium at Kuumba. Discussion topics include black feminism, HIV and sex work. Mr. Roberson will speak on how ballroom culture fits into the history of black resistance.

Then comes the ball itself, with competition categories that mark both the joy and solemnity of Black History Month. Those wanting to win "Realness," for example, require costumes that invoke civil-rights leaders, while those strutting for "Runway" must pay homage to Haitian voodoo, in honour of the enslaved people from that island nation who successfully fought for their freedom.

While Mr. Hay has received some negative feedback, the men are confident their work will pay off.

"Black liberation right now just means to get those missed voices and including them in the conversation," says Mr. Miyake-Mugler. "Find out why they're feeling like they're not free."