‘Expectations have never been so high for a minister of justice,’ says one legal scholar about the challenges facing Jody Wilson-Raybould.

ADRIAN WYLD/THE CANADIAN PRESS

There's a family story about a young Jody Wilson, out playing with her sister, Kory. In an empty yard across from their house, they stumbled on a beehive. Kory, who is 14 months older, stopped short, suggesting they leave the bees to their business. But five-year-old Jody forged ahead, seeking confirmation of the occupants. She returned home swollen with stings.

Talking to the people who know her well, one gets the feeling that Canada's new Justice Minister and Attorney-General has never really stopped poking at beehives. In Grade 7, for a speech contest, she shared stories of the countless stitches acquired on her childhood adventures on Vancouver Island. When the sisters graduated from law school in 1999, their mother, Sandy, had their baby shoes bronzed to mark the milestone: Kory's were pristine; Jody's were creased and worn.

She set off brazenly from there, serving for four years as a Crown attorney in the courtroom trenches of Vancouver's Downtown Eastside; slogging, for another five, through negotiations with the province and Ottawa as a member of the British Columbia Treaty Commission; and then running, in 2009, for the post of B.C. regional chief, eventually winning two terms in the rough-and-tumble arena of aboriginal politics.

The beehive-poking moment they still talk about in B.C. is known as her "With all due respect, Mr. Prime Minister" speech: While addressing a gathering of government officials and aboriginal leaders in 2012, she stared down Stephen Harper, seated in the front row, and rebuked Ottawa for its "neo-colonialism."

But, for Ms. Wilson-Raybould, the turning point came one year later, during the Idle No More protests, as she was sitting in the prime minister's office in the Langevin Block. With a crowd chanting outside, and acting in her capacity as B.C. regional chief, she presented a detailed strategy for First Nations self-government. Mr. Harper all but ignored it.

So, when Justin Trudeau came calling, Jody Wilson-Raybould was ready to listen. Five months ago, after winning the newly created riding of Vancouver Granville with 44 per cent of the vote, she was sworn in as Canada's justice minister. It was arguably the defining moment of a day that was itself remarkable for the unprecedented ethnic and gender diversity of the country's new cabinet. People wept – in their seats at Rideau Hall, in their living rooms in British Columbia, and across the country – as the first aboriginal Canadian was named to run the department that had designed, more recently than many Canadians like to remember, the laws and legislation that created residential schools, stripped this country's aboriginal women of their rights based on whom they married, and effectively rendered indigenous people second-class citizens through the Indian Act. As the new minister would point out two weeks after the cabinet swearing-in, during a speech at Simon Fraser University: Just over half a century ago, she wouldn't have even been allowed to vote.

There is a tendency, at such a historic tipping point, for the symbolism of Ms. Wilson-Raybould's appointment to become a distraction from the person taking office, drifting uncomfortably close to tokenism. A woman! A First Nations woman! But, the emotional weight of her appointment aside, in the last 30 years "expectations have never been so high for a minister of justice," suggests Adam Dodek, a legal scholar at the University of Ottawa.

After a long career fighting proudly for indigenous rights, she is now sitting on the other side of the table, as the representative of the Crown. It will be impossible to make everyone happy, not least herself. And the success or failure of the new government in which she sits is riding, in no small part, on how well she does her job.

Making history was easy by comparison. Jody Wilson-Raybould, it's safe to say, has just confronted her biggest nest of bees.

‘I think we’re all on a quest to achieve justice,’ says Ms. Wilson-Raybould, seen here with Prime Minister Justin Trudeau at the cabinet swearing-in last fall.

ADRIAN WYLD/THE CANADIAN PRESS

A LONG LINE OF TRAILBLAZERS

It's Monday morning, and the head of Canada's legal system is running late. When she finally sits down in a boardroom in the Justice Building, she smiles upon learning that her sister shared the bee story, and volunteers that she herself was in the emergency room almost every week, growing up. But, Ms. Wilson-Raybould points out, "I have changed a lot since I was a kid. I am not a huge risk-taker any more."

The message is clear: When it comes to rewriting Canada's laws, she'll step carefully.

When the Prime Minister told her that she was getting the justice portfolio, she says, two thoughts immediately ran through her mind.

The first was the importance of her appointment for the nation's indigenous people.

The second: physician-assisted death. Of all the responsibilities on her plate, and there are many, this is certainly the most pressing – drafting the legislation that will detail how Canadians suffering from debilitating or terminal illnesses will be able to direct a doctor to help them die. One of the first actions out of her office was to request a six-month extension to a deadline set by the Supreme Court, which last February struck down the country's prohibition on doctor-assisted dying – and gave Parliament a year to pass new legislation, or see the court decision itself become law. In the end, the court gave the Liberals another four months, until June.

Justice minister promises ‘substantive’ discussions about right-to-die legislation

2:13

But that's only the top item on her to-do list. Ms. Wilson-Raybould is also tasked with legalizing marijuana; improving outcomes for aboriginal and mentally ill people in the justice system; unravelling laws passed by the previous government, including those involving mandatory minimum sentences; and reviewing all outstanding court cases involving the Crown, to decide whether – and how – they should continue.

With the retirement of Justice Thomas Cromwell in September, and the pending retirement of Chief Justice Beverley McLachlin (who is mandated to step down by fall, 2018), she has two key judicial appointments to oversee, on top of the ongoing number of lower-court vacancies that the Justice Department must regularly fill. Along with Carolyn Bennett, the Minister of Indigenous and Northern affairs, Ms. Wilson-Raybould has been put in charge of the inquiry into the murders and disappearances of hundreds of indigenous women.

‘It’s time for justice’: Liberals launch inquiry into missing, murdered indigenous women

2:16

And, as the country's attorney-general, she also serves as the legal adviser to all her colleagues around the cabinet table. "You could have no policy ambitions in the job," says Prof. Dodek. "That [alone] could absolutely consume the minister's time 24/7." But Ms. Wilson-Raybould has a list "that touches on some of the most critical social issues in our country."

According to Prof. Dodek, you'd have to go back to Jean Chrétien in 1980 to find a justice minister with such an ambitious mandate – and his one job was to bring home the Constitution and enact the Charter. Indeed, one could argue, Prof. Dodek suggests, that Mr. Chrétien had the lighter load.

But while Ms. Wilson-Raybould may be a novice MP, she's hardly new to complicated problems, or political hurdles. She comes from the Musgamagw-Tsawataineuk/Laich Kwil Tach people of northern Vancouver Island, and bears the name Puglaas, bestowed upon her in a potlatch ceremony when she was 7. It means "woman born of noble people" – she comes, in fact, from a long line of trailblazers – and it carries the expectation of leadership in her clan.

"We were brought up to believe in ourselves" she says, recalling her childhood with her sister, "and to know where we come from."

How else to see where you're meant to go?

A THREAD OF DESTINY

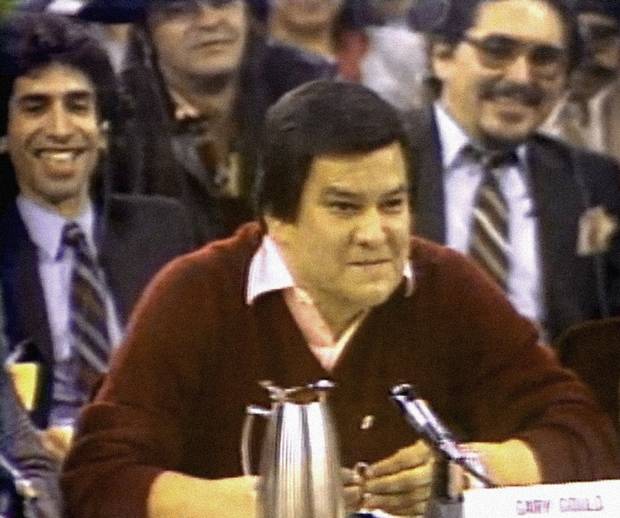

During the election campaign last fall, in one of those rhyming sequences that make historians delight, a 32-year-old video resurfaced in which the father of the future justice minister spars with the father of the future prime minister. They are sitting across from each other at the 1983 constitutional conference on native issues in Ottawa. Bill Wilson, then vice-president of the Native Council of Canada, tells Pierre Trudeau, "I have two children on Vancouver Island, both of whom, for some misguided reason, say they want to be a lawyer. Both of whom want to be the prime minister."

He then pauses for effect. "Both of whom, prime minister, are women."

At that, the mostly male audience guffaws loudly – a telling sign of the times. The camera turns to Mr. Trudeau, leaning back in his chair. "Tell them I'll stick around until they're ready," he quips.

There's another pause for more laughter. "I'm informed," Mr. Wilson says, "that one of them could be out here on a plane this evening."

Like many good tales, the truth isn't so tidy. As it happened, Jody and Kory were watching the exchange live in a school assembly, red-faced about being singled out. Neither particularly recalls dreaming of being prime minister, and Mr. Wilson acknowledged in a recent interview that he was actually thinking that Kory, the more serious, scholarly student, would be the one catching that flight to Ottawa.

"I think my sister was the smarter one," Ms. Raybould-Wilson says, smiling. "I was a jump-off-the-roof sort of kid. I got into trouble all the time." Stories abound. Her mother recalls how her younger daughter liked to climb to the very top of the playground swings. And how, on the first day of Grade 3, she was marched to the principal's office for refusing to do her work. The reason her mom remembers that day so clearly? She was the teacher.

Jody was a clever, if indifferent, student. Her high-school academic adviser, Tim McKinnon, tells of a parent-teacher meeting at which he and Sandy Wilson insisted that Jody, over her protests, take subjects that would keep her options open in university. "Let's get you through high school, Jody," he remembers joking. "Then, if you want to be a ditch digger after that, fine."

He says now, "Had you looked at Jody's grades in high school, would you say she was bound for great things? Maybe not … but in my experience over a long career, it's an attitude toward life, it's energy – and a feeling about yourself and your abilities – that makes people successful. And that's certainly worked out in Jody's case.

Lively youth aside, her story is woven with a thread of destiny. Ms. Wilson-Raybould comes from a prominent family of the We Wai Kai Nation, and she has a home on the Campbell River on the Cape Mudge reserve, not far Comox. Her paternal grandmother, Ethel Pearson, helped to start the B.C. Native Courtworkers Association, and was active in fighting for Bill C-31, which restored status to indigenous woman who had lost it when they married non-indigenous men. Her father was the second indigenous person to graduate from UBC's law school. (His cousin Alfred Scow was the first, and became the first indigenous judge appointed to the B.C. Provincial Court.)

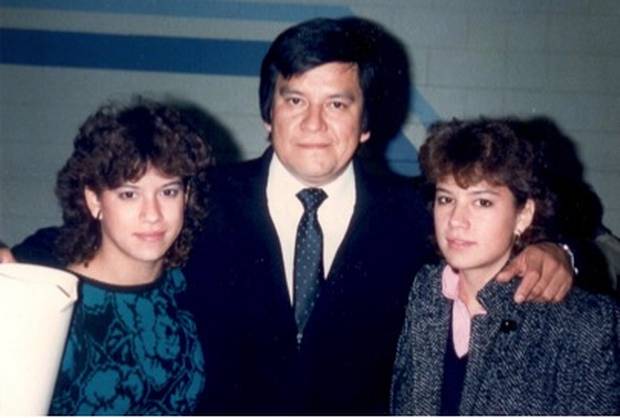

The Wilson sisters with their father, Bill.

PHOTO COURTESY OF KORY WILSON

Mr. Wilson became a prominent indigenous leader and activist, and served as spokesman for the Native Council of Canada in 1983, to push for Section 35 of the Constitution Act, an amendment that affirms indigenous rights, and would later guide his daughter's work as regional chief. Her accomplished sister was recently named executive director of aboriginal initiatives and partnerships at the British Columbia Institute of Technology.

Her family, however, was not spared the hand of the law. Many of Ms. Wilson-Raybould's relatives attended residential school. Her father, one of the youngest in his family, escaped only because, when officials came to get him, his own father, by then a well-off businessman in Comox, refused to let him go. Her grandmother, Ms. Pearson, although a respected elder, was among the indigenous women stripped of native status – her second marriage was to a white man. In contrast, Ms. Wilson-Raybould's non-native mother gained status by marrying Bill Wilson, shortly after they graduated from high school together in Comox.

Sandy Wilson worked hard to provide for her two daughters.

PHOTO COURTESY OF KORY WILSON

The marriage didn't last long; Jody was born in Vancouver while her father was midway through law school, and she doesn't remember a time when her parents were together. After the split, the two girls moved around with their mother, who worked as a grade-school teacher, before they settled back in Comox, to be close to their extended family.

They didn't have a lot of money, but Ms. Wilson worked hard to keep the family afloat; her daughters didn't feel deprived. When a full-time teaching job wasn't available, their mother worked as an in-patient clerk at the local hospital, making sure the girls got to their competitive swimming practices and kept up with their studies. When they were in high school, she slept on the living-room couch so they could have their own bedrooms.

Mr. Wilson would visit from Vancouver, but credits his former wife with raising the girls to be who they are today. From his family, though, they acquired much of their knowledge of indigenous politics. Ms. Wilson-Raybould recalls him taking them, even as young girls, to his meetings with provincial indigenous leaders and chiefs, where they would sit under the table as the debates unfolded. In the kitchen on the reserve, or at their grandmother's home in Comox, treaty rights and the Indian Act were regular topics of discussion. "As much as we wanted to go out and play with our friends," she recalls, "we were told to sit and listen to the discussions taking place, whether around the land question or self-government."

She says it was clear from a young age that, guided by her roots, an activist family and the expectations of a strict single mother, she'd better make something of herself. In a school where she and her sister were among the few aboriginal students, Mr. McKinnon says, Jody was known for holding her own, defending herself if she felt a teacher was in the wrong, or confidently debating her classmates. "She would say whatever the hell she wanted to say," recalls Mr. McKinnon, who served as her academic coach throughout high school. "She could definitely hold her own."

Looking back on that time, the minister says, she realizes she was insulated from a lot of the problems that plague many First Nations people; although they may have been stuggling financially, the people of Cape Mudge shared " a strong sense of community." She recalls few direct personal experiences with racism, beyond the story of a day in elementary school, when she was called down to the office so that a dental hygienist could check her teeth. Upon learning that only the indigenous students were receiving the check-up, Sandy Wilson marched down to the office herself. Her daughters' teeth were her business.

That was the last time Jody and Kory were singled out.

Ms. Wilson-Raybould, third from the left, stands beside her mother and sister, surrounded by Kory Wilson’s daughters Kaylene (left), Kaydence (second right) and Kaija (right).

PHOTO COURTESY OF KORY WILSON

A VOICE FOR SELF-GOVERNMENT

"I loved being in court," she recalls of her nearly four years, starting in 2000, as a crown attorney at the Vancouver Criminal Courthouse in the Downtown Eastside. "I loved being able to articulate arguments in front of a judge, and having to think on my feet."

After a brief stint in traffic court, she spent long days juggling just about every kind of legal matter – guilty pleas, bail hearings, judge-only trials. She witnessed firsthand a grim Canadian reality: the disproportionate number of aboriginal defendants, and those poor and fighting addictions, who become entangled in the justice system – often on a relatively minor first offence – and then get stuck in a revolving door of charges, jail stints and probation violations.

"She was a very competent person," recalls defence lawyer Chris Johnson, who faced her in court. He describes her as a "firm but fair" prosecutor. "She is no pushover, but she would consider different ways to resolve matters, and certainly always listen."

She was also the only indigenous lawyer working for the Crown at the time. "I was sorry to see her go," says Mr. Johnson. "She added a completely new perspective that [we] didn't have before, or much since."

In 2003, Miles Richardson, then head of the treaty commission trying to settle land claims in B.C., offered her a job as a senior adviser. Ms. Wilson-Raybould became a lead voice at the table, eventually rising to the position of an elected member of the commission, and then acting chief commissioner.

It was during this time that she met Tim Raybould, a Cambridge PhD and long-time consultant with the Westbank First Nation on Lake Okanagan. They were married seven years ago in a traditional ceremony at Cape Mudge. Now that she is based in Ottawa, he will spend half his time there, too. (They don't have children, but are close to Kory's three daughters, whom they regularly take on vacations to such places as Florida and Las Vegas.)

Tim Raybould, Ms. Wilson-Raybould and her three nieces.

PHOTO COURTESY OF KORY WILSON

Mr. Raybould also became his wife's first controversy – when it was discovered he had registered as a lobbyist this year on behalf of Westbank and of the First Nations Finance Authority, a not-for-profit that provides loans and financial advice to indigenous communities. Critics quickly called this a conflict of interest; in an e-mail to The Globe, the minister said her husband registered officially to "be very transparent" about his long-time career advising First Nations governments on policy matters. "I take my ethical obligations very seriously."

She'd been at the Treaty Commission for seven years when a chief from Cape Mudge nominated Ms. Wilson-Raybould for the position of regional chief – a role in the big leagues of aboriginal politics that would vault her onto the executive committee of the Assembly of First Nations (AFN). She won the vote by a significant margin, and, at 38, officially started a life in national politics.

She stayed for two terms, the only woman at the AFN table. It wasn't always easy. She got used to having an idea that she put forward being ignored, and then picked up by a male chief and suddenly being deemed worthy of attention. "For me, as long as it gets talked about, all the better," she says. "But in my experience, sometimes some voices are listened to more than others."

While negotiating treaties, she recognized that First Nations would have a better bargaining position if they were self-governing, and became an expert in the subject. She and her team drafted three connected documents, totalling 900 pages, that former prime minister Paul Martin, who has known her for years, calls "as good as anything I have read on governance." It included a carefully researched binder of best practices, a self-assessment for band councils to determine how well-prepared they are to be self-governing, and a guide to begin the steps toward self-government.

Ms. Wilson-Raybould was aware of the need for good governance that was accountable to the people. As she would later say in her public speech at the 2012 Crown-First Nations gathering, "Too many of our people don't trust their own governments, and quite frankly," she added, looking pointedly at Mr. Harper, "they don't trust yours, either."

Her impatience with the slow progress being made – and what she perceived as indifference from Ottawa – came to a head during the Idle No More meeting in 2013. With the protesters gathered outside on Parliament Hill, she and a number of other chiefs met with the prime minister, over the objections of many people in the First Nations community. When it came time for Chief Wilson-Raybould to speak, she laid out her self-governance initiative, proposing a "reconciliation framework" that would guide programs in each government department.

In his concluding remarks, she says, Mr. Harper conceded that, although Ottawa knew it had to change the Indian Act, nobody had any good ideas on how to go about it. "But I had just presented the solution that was developed in our region," she recalls. "For me, that created an incredible level of frustration."

By the time Justin Trudeau sat down with her in July, 2013, during an AFN meeting in Whitehorse, she was considering her future path. The two spoke privately for more than an hour, talking about their visions for the country, reminiscing about their political fathers – the first of several conversations. Seven months later, she co-chaired the party's biennial convention in Montreal; six months after that, she was acclaimed the Liberal candidate in Vancouver Granville.

For all her years in national indigenous politics, she had never belonged to a party before. "Why do you want to do that?" her mother recalls asking, in reference to her daughter's decision to run for federal office. "She said, 'I have done all I can. I have to get to a higher level.'"

Says the minister herself: "If you want to see change, if you want your voice heard, you need to be sitting at the table."

Trudeau: ‘It is time for a renewed nation-to-nation relationship’

2:06

THE SEARCH FOR BALANCE

From her fourth-floor office, the minister has a clear view, across Ottawa's Wellington Street, to the Supreme Court. Sitting at her desk a few days into her new job, Ms. Wilson-Raybould picked up the phone and called Chief Justice McLachlin. "I am not sure this was appropriate," she says now, but she wanted to offer her "thanks to the court."

She recalls telling the Chief Justice, "I really respect a lot of the decisions you have made with respect to indigenous rights. I hope it's okay to say that."

Chief Justice McLachlin assured her: "It's always okay to give a compliment."

Their exchange is telling evidence of the shift in philosophy at the Justice Department. It's safe to say that under the Conservatives, whose policies were often frustrated by rulings from the court, such pleasantries were rare.

Even within the context of the Liberal government's ambitious, and decidedly liberal, new agenda, Ms. Wilson-Raybould brings a unique vision to the justice portfolio. Although she is only the third woman to hold the job, she brings something even more change-making to her new post: her indigenous background. "There are things that she will see and questions she will ask and perspectives she will have that even the most well-intentioned non-First Nations wouldn't see," says Kim Campbell, the country's first woman justice minister. (Anne McLellan was the second.) "That diversity bodes well for expanding the scope and the understanding of justice."

On that subject, Ms. Wilson-Raybould speaks repeatedly about balance. When talking about justice policy, she refers to ensuring the "balance between individual choice and protecting [the] vulnerable." When it comes to sentencing, she talks about ensuring "that our approach doesn't discriminate against people."

She stresses the need for consensus-building and compromise, referring, in a speech at UBC last month, to the way her ancestors settled disputes – a sharp contrast, she said, to the "partisan" environment in Ottawa. "I don't think I will ever get used to the type of politics and etiquette in the House of Commons," she said, "particularly during Question Period."

In that same speech, she also discussed the need to build "off-ramps to the system" – that would address the factors that lead to criminal behaviour, and would prevent young people (too often young, indigenous men, she specifies) who commit non-violent first offences, from becoming trapped in the system. Part of her mandate from the Prime Minister includes the expansion of restorative-justice measures as an approach to less-serious criminal cases.

In her recent meeting with her provincial counterparts, meanwhile, she requested input on best practices that could be shared nationally. "We can take a more holistic community approach," says Ms. Wilson-Raybould. Asked to name what she considers a successful program, she cites Vancouver's Downtown Community Court, where the government provides services related to health, justice and social needs in one location.

In addition, she is expected to reverse the Conservative policy of mandatory mininum sentences. "I think it's very important," she says, "for judges to be able to reflect on what they hear, and make decisions based on the reality for the person who has come before them."

A sense of how she plans to go about her agenda may be in part revealed by some of the people she consulted after taking the post. Along with Mr. Martin and Ms. Campbell, they included former justice minister Irwin Cotler.

In interviews, all three made the case that Ms. Raybould-Wilson's background is a chance to find new solutions to problems that have plagued Canada for decades. "The justice portfolio is the most fun you can have as a lawyer. It is really at the heart of what so much of government is about," says Ms. Campbell. "But it also requires you to reach out and really understand the social significance of what you are doing."

She advises Ms. Wilson-Raybould to be patient, to build trust among her colleagues, and to choose her battles wisely. In general, she says, every minister has to remember that her views and opinions may be at odds with others around the cabinet table. But Ms. Wilson-Raybould's job is that much easier, she says, because many of the deliverables outlined in the justice mandate were promised during the election. She also has at her service a department of newly emboldened lawyers charged with tackling an exciting agenda with an "evidence-based" approach.

Mr. Martin argues that, as the voice of the Crown, the new justice minister's background – and her fiercely held views about indigenous rights – is a strength she brings to the job, inasmuch as it provides a deep understanding that has been lacking in Ottawa. Referring to the long line of white men who preceded her, says Martin, "Nobody – nobody – asked the question, 'Does he have a conflict of interest?'"

'SOMETHING IMPORTANT TO ME'

Not long ago, a father, a second-generation Chinese-Canadian, stopped Ms. Wilson-Raybould at Pearson Airport in Toronto to tell her that her appointment is an empowering symbol of the future for his young daughter. Ms. Wilson-Raybould is mindful of her responsibility to mark the way for others, and says that she approaches her cabinet position, and her role as an MP, "through the lens of my own experience, my own feeling of injustice."

And like many Canadians, she has her own memory of a loved one's death. She sat with her maternal grandmother through the last days of life, when the effects of a stroke had put her into palliative care. The minister is reluctant to give full details, but her mother explains that Ms. Wilson-Raybould took a break from law school at UBC to travel back to Vancouver Island, barely leaving her grandmother's bedside for a week. "It's something I have to do," her mother recalls her saying when she urged her daughter to go back to school. Finally, her mom told her, "Honey, I don't think she will go with her granddaughter sitting beside her," and Ms. Wilson-Raybould reluctantly took the ferry back to school. Her grandmother passed away in her sleep not long after.

"Being there for her was something important to me," she says, acknowledging that the experience has had an impact on her views of physician-assisted dying. "For me, it stressed the need to provide the most comfort to people when they are nearing the end of her life, whatever form that takes."

Adds Ms. Wilson-Raybould, "As minister, but just generally as a member of Parliament, and also as a human being, I think we're all on a quest to achieve justice, and in order to do that we need to recognize the incredible diversity that exists out there, and create the legal and political space to ensure that all people can benefit and thrive."

Even if that means poking a beehive or two along the way.

Erin Anderssen is a senior feature writer with The Globe and Mail.