Sex work and the rules around it have dominated Parliament Hill chatter. The second stage of the federal government's race to pass a bill governing prostitution by the end of the year has begun, with the Senate legal and constitutional affairs committee beginning hearings. This comes after the House of Commons justice committee's rare summer sitting on Bill C-36, which was tabled in June, six months after the Supreme Court struck down some of Canada's prostitution laws. Dozens of witnesses have spoken about the bill, with some supporting it and others calling for it to be amended or scrapped altogether.

Here's a glance at what the government is proposing, and what critics say about the changes.

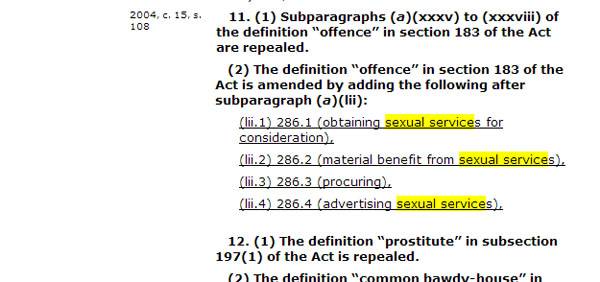

1. Going after the buyers

The bill criminalizes the buying of sex – or “obtain[ing] for consideration… the sexual services of a person.” The penalties include jail time – up to five years in some cases – and minimum cash fines that go up after a first offence.

2. What’s a “sexual service”?

The bill doesn’t say, meaning it would likely be up to a court to decide where the line was drawn. A government legal brief, submitted to the committee as it considered the bill, says the courts have found lap-dancing and masturbation in a massage parlour count as a "sexual service" or prostitution, but not stripping or the production of pornography.

3. What about sex workers?

They also face penalties under the bill, though the government says it is largely trying to go after the buyers of sex. Under the bill, it would be illegal for a sex worker to discuss the sale of sex in certain areas – a government amendment Tuesday appears set to reduce what areas would be protected – and it would also be illegal for a person to get a “material benefit” from the sale of sexual services by anyone other than themselves. Some critics have warned that latter clause could, for instance, prevent sex workers from working together, which some do to improve safety.

4. What about those who work with sex workers?

Anyone who “receives a financial or other material benefit, knowing that it is obtained by or derived directly or indirectly” from the sale of a “sexual service,” faces up to 10 years in prison. This excludes those who have “a legitimate living arrangement” with a sex worker, those who receives the benefit “as a result of a legal or moral obligation” of the sex worker, those who sell the sex worker a “service or good” on the same terms to the general public, and those who offer a private service to sex workers but do so for a fee “proportionate” to the service and so long as they do not “counsel or encourage” sex work.

5. Can sex workers advertise their services?

This is a key plank of the bill, which makes it a crime to “knowingly advertise an offer to provide sexual services for consideration,” or money. This could potentially include newspapers, such as weekly publications that include personal ads from sex workers, or websites that publish similar ads. Justice Minister Peter MacKay appears to believe the ban could go after such publications. “It affects all forms of advertising, including online. And anything that enables or furthers what we think is an inherently dangerous practice of prostitution will be subject to prosecution, but the courts will determine what fits that definition,” he told reporters after speaking to the committee July 7. This has been welcomed by some, including Janine Benedet, an associate professor at the University of British Columbia who supports the bill overall, though she called for some changes. “I didn’t actually expect to see this advertising provision in this bill but I would say it’s actually a really important step, to say that kind of profiteering needs to stop,” she said.

6. Can anyone still advertise the sale of sex?

Yes – sex workers themselves. The bill includes an exemption that says no one will be prosecuted for “an advertisement of their own sexual services,” though platforms that actually knowingly run the ads may face prosecution.

7. What else is in the bill?

It expands the Criminal Code’s definition of a weapon to including anything “used, designed to be used or intended for use in binding or tying up a person against their will,” a change the head of the Canadian Police Association welcomed. The bill also sets mandatory minimum sentences of at least four years in prison for kidnapping cases that involve exploitation, or any similar case where a person’s movements are limited – steep new penalties. The bill also gives a judge new powers to order a sex ad seized or deleted – by amending a clause that previously extended those powers in cases of child pornography or voyeurism.

The government has pledged $20-million over five years in new funding to help sex workers get out of the trade. However, Ottawa hasn’t said specifically how the money will be spent and various critics, including police chiefs, have warned it’s too little.

8. What brought us here?

The Supreme Court struck down Canada’s existing laws last December – namely, a ban on keeping or being in a “bawdy house,” or brothel; a ban on “living on the avails of prostitution,” since largely reworded as the “material benefit” ban; and a ban on communicating in public for the purposes of prostitution. The court generally said the provisions violated the Charter by threatening sex workers’ rights to life, liberty and security of the person. That’s essential, because critics are warning the new bill does the same thing, and is therefore vulnerable to a Charter challenge. “The new bill does not respect our constitutional right to life, security and liberty,” sex worker Émilie Laliberté told the committee.

The group whose challenge led to the December Supreme Court decision has already promised another legal fight.

9. Why is the government doing this?

They’re doing it now because the court forced their hand – without a new law, Canada would simply not have any laws on the books against prostitution by December. Some witnesses have called for that, but that’s not what government is doing. Conservative MP Stella Ambler, who is on the Justice Committee considering the bill, has flatly called the bill an “anti-prostitution law,” and the Justice Minister has said it’s the government’s aim to limit the sex trade as much as possible.

The opposition parties have opposed the bill. But both the NDP and Liberals have avoided getting into specifics about how they would have responded to the court’s ruling.

10. What’s the status of the bill?

Once done at the committee, it will return to the House of Commons, which is scheduled to return from its summer break Sept. 15. It is now working its way through the Senate. Canada’s current laws, struck down by the Court, officially expire in December, and the government has pledged to pass Bill C-36 by then.

Produced by digital politics editor Chris Hannay.