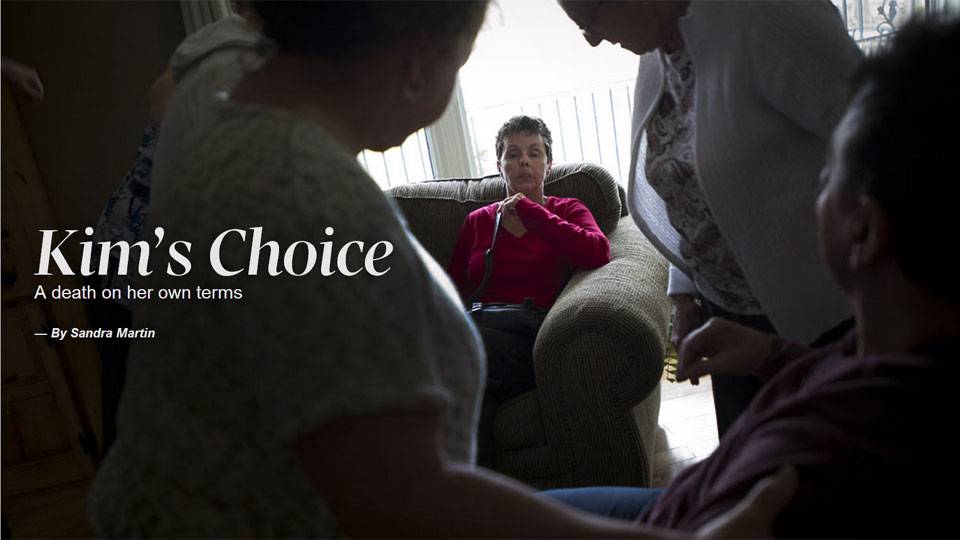

‘I have a plan,’ Kim Teske, left, with her sister Deanna Smith in May, 2014, told Sandra Martin. She was suffering from Huntington’s, but none of her doctors would help her die. She hoped her death from starvation would spur change.

Kevin Van Paassen/For The Globe and Mail

About three years ago, a senior editor some two decades my junior invited me into his office, a ramshackle enclave dubbed "the sunshine room" because the walls were painted a noxious shade of yellow. After tapping on his BlackBerry for several minutes while I computed my potential severance package versus my outstanding mortgage payments, he pulled his gaze away from his screen, peered at me quizzically and announced my new assignment: Find somebody who wants to die and write about it for the paper.

"Do you have the stomach for such a story?" he asked.

"Of course I do," I retorted with my customary defiance, eyes flashing at the notion that I might not have the same byline hunger as a young hire fresh out of J-school. After sharing the lives and deaths of at least a dozen people since then, I have learned that guts have nothing to do with pain, loss and grief. What you need is an open heart to appreciate another person's suffering. That is the lesson the dying and their families have taught me.

Heart is at the essence of the unanimous Supreme Court ruling in the Carter case, which overturned the ban on physician-assisted dying in February, 2015. People who are "grievously and irremediably ill" face "a cruel choice," the judges wrote in one eloquent voice. They must either kill themselves prematurely, "often by violent or dangerous means," or they must endure "severe and intolerable suffering" until they eventually die of natural causes. The Carter decision was based on suffering and the autonomy rights of patients to determine the point at which life had become intolerable for them.

The long-awaited legislative response goes in the opposite direction, moving the decision-making power away from patients and putting it squarely back in the hands of physicians by introducing "reasonably foreseeable" death as an additional qualification to "a grievous and irremediable medical condition" that is "intolerable to the individual."

Bill C-14, which was tabled in the House of Commons on Thursday, has far too little heart and far too much head. It is lodged firmly in the mindsets of risk-averse bureaucrats and politicians. The government bill is cautious, pragmatic, and above all, designed to pass in the narrow two-month window before the Carter ruling comes into force on June 6, 2016. What has so spooked the majority Liberal government that it has retreated from Carter and abandoned the persuasive recommendations of its own parliamentary committee?

I don't know the answer, but I wonder if it has something to do with the vote-rich coalition of religious and community groups claiming to speak on behalf of the vulnerable, as well as the powerful professional associations espousing the autonomy and conscience rights of doctors and health-care institutions. They are certainly bombarding my electronic inbox with warnings, petitions and safeguards, some of which are patently unconstitutional. Former Conservative MP Steven Fletcher, who is a quadriplegic, eloquently confronted medical opposition to physician-assisted dying in a presentation before the Parliamentary committee late in January. "To the doctors and the medical profession," he said, "be professional, be tough." Assisted dying is "not about you," he said. "It's not about the medical profession. It's about the individual and his or her choices."

Many people shared traumatic and sometimes horrific experiences with me, both on and off the record, in the course of my research for articles in The Globe and Mail and for my book, A Good Death: Making the Most of Our Final Choices. Tears were often shed in the telling and the listening, and I make no apology for that. I heard about a couple determined to die before old age and incapacity forced them to move out of their house and into long-term care. Even though he was a doctor and had access to barbiturates and sedatives, he miscalculated the lethal cocktail necessary to kill either his pain-wracked and opiate-addicted wife or himself. He ended up on life support in a local hospital until his grown children agreed to pull the plug, and she spent two years in misery and deepening depression in institutions before she finally died.

Human stories have the power to transform others, and that is what happened to me in writing about people like Kim Teske. She had inherited the gene for Huntington's, a ghastly neuro-degenerative disease that combines elements of Alzheimer's, Parkinson's and schizophrenia.

"I love life and I love me," she told me many times, insisting that she did not want to end up in an institution like her older brother Brian, waiting for either a feeding tube or to choke to death. "I have a plan," she insisted. Kim wanted to send a political message that the law should be changed to allow people facing a hideous sentence a peaceful exit. That's why she told me her story.

Kim Teske’s apartment is packed up in Orangeville, Ont., Friday May 9, 2014. Ms. Teske, who suffered from Huntington’s disease, passed away a week earlier.

Kevin Van Paassen/For The Globe and Mail

Kim knew from watching Brian's deterioration that she could have lived several more years, becoming increasingly disabled, but that is not what she wanted. None of her doctors would help her die or even discuss options with her. In desperation, she turned to the Internet and, with the help of one of her computer-savvy sisters, found Dying with Dignity. The organization would not provide the means, but people there listened to her, took her seriously and explained that starvation and dehydration were the most reliable and legal way of ending her life in this country.

She died in May, 2014, in her own bed, surrounded by her supportive family after refusing food and drink for 12 days. Nobody thought she could stick it out, least of all me. It was too hard, especially for somebody like Kim, who loved to eat, drink and party, but she did it, amazing us all with her courage and determination.

It is hard to know whether people like Kim will qualify for medical assistance in dying if Bill C-14 becomes law. Was her death "reasonably foreseeable"? The same is true for the three patients who formed the basis of the Carter challenge. Kay Carter was afflicted with crippling spinal

stenosis that forced her to spend her days and nights flat on her back "like an ironing board." She had gone to a clinic in Switzerland for an assisted death, and her family later joined the court challenge on her behalf. Gloria Taylor, like Sue Rodriguez, had ALS, a neuro-degenerative disease that causes muscles to atrophy until the patient, who remains cognitively intact, can no longer speak, swallow or breathe. Dying, usually from respiratory failure, is said to be like drowning in your own phlegm. Would that death qualify as "reasonably foreseeable" and if so, at what stage of the disease?

The question is moot for Ms. Carter, and for Ms. Taylor, who died suddenly of a massive bowel infection in October, 2012, but it is top of mind for Elayne Shapray, the final patient in the Carter challenge. She has progressive multiple sclerosis, which severely limits her independence and her ability to care for herself, but is her death "reasonably foreseeable"?

On Thursday, her husband, lawyer Howard Shapray, responded to Bill C-14 with a sharply worded statement to the Minister of Justice, calling the bill "an insult to those who struggle with and endure interminable illnesses that create pain and suffering but which do not cause death." Mr. Shapray said it was "shocking" that the government would table a bill that goes against the "spirit" as well as "the substance" of a trial decision that was "affirmed by the Supreme Court of Canada."

The "people you seek to deprive of a dignified physician-assisted death are those who may need it the most and who are not in the least bit 'vulnerable,' " he concluded.

The bill seems to be directed at end-stage cancer patients, people for whom death is a given, even if the timing cannot be predicted precisely. It shuns people with refractory depression, those who are under 18, and denies access to dementia patients who have stated their end-of-life wishes in advance directives completed after diagnosis but while they were still competent. Who will speak for the suffering for whom no end is in sight? Not Parliament, not for at least five years after the passage of this safe bill.

Let me tell you what desperate people do when life becomes intolerable. They turn their faces to the wall and wait for a slow death, they empty their bank accounts to fly to Switzerland, they guess at lethal doses and often end up in worse shape, they buy guns and ropes and resort to all manner of scary and unreliable exits. I talked with the family of a man who twice ordered expensive barbiturates, once from Mexico, another time from China. They never arrived. Finally, he rented a helium tank, put a plastic bag over his head and pumped in the gas until he suffocated.

If we do not listen to suffering patients and offer them peaceful exits, they will find their own solutions, and that includes underground death providers. After Sue Rodriguez lost her case at the Supreme Court and then died by suicide with the help of a mystery doctor, Austin

Bastable, a tool and die maker from Windsor, Ont., who was paralyzed from acute multiple sclerosis, became the first Canadian to die with the help of Jack Kevorkian, a.k.a Dr. Death.

Mr. Bastable had already tried to take his own life by ingesting his stockpile of pills while his wife was at work. She discovered him and called emergency services. Three days later, when he woke up in hospital, she looked at him and said, "I'm so sorry." That was when she realized, as she explained on an episode of the CBC Television program Man Alive, that as much as she wanted her husband to live, it was cruel to thwart his desire to die. No matter how much she would miss her husband, she recognized that life had become intolerable for him. Letting him die was the ultimate act of love.

Dr. Donald Low and his wife Maureen Taylor recorded a plea on video in 2013 for physician-assisted death. ‘A lot of clinicians have opposition to dying with dignity. I wish they could live in my body for twenty-four hours, and I think they would change that opinion,’ he’s said.

I've heard that sentiment many times. Journalist Maureen Taylor and her late husband, Donald Low, tried desperately to find the means for a fast painless death for him after he was diagnosed with a malignant brain tumour in February, 2013. She shared a journal entry with me in which, overcome by grief, she silently implored her husband to "hang in there a bit longer … I'm not ready to let go of you." The moment passes because she realizes, "that's not how he feels."

Together they made a video in which Dr. Low, slumped on a chesterfield, one eye closed, the other eyelid taped open, made a plea for physician-assisted dying. "A lot of clinicians have opposition to dying with dignity," he said. "I wish they could live in my body for 24 hours, and I think they would change that opinion."

It was not dying that he feared; it was the protracted process in which he would be drugged into unconsciousness and unable to communicate with his family. Yet that is how Dr. Low died several days later. Palliative care can dull the pain and sedate you until you die, but it cannot give you control or choice. Dr. Low had the best palliative care available, but it was not what he wanted. And it was not what his wife wanted for him. She told me later, lying beside her husband on his death bed was like "sleeping with a corpse."

Of course we need better resources for palliative care and greater access to it, especially in remote and rural areas and in long-term-care facilities. But it does not work for everybody, as the late palliative-care specialist Larry Librach testified at the Carter trial in British Columbia in 2012. "After careful reflection, I have come to the personal opinion," he told the court, that "the provision of quality palliative care will not answer the wishes of all persons who are dying and that we as a society need to deal with this issue through the courts and through Parliament." The courts have spoken; alas, Parliament was not listening hard enough. Even palliative sedation will probably not be available to patients in the excluded categories at the point where they have determined life has become intolerable.

Like most of us, I'd like to think that I will live forever or that I will fall asleep some night and never wake up. That is unlikely to happen, especially since the majority of us – some put it at 70 per cent – will die in hospital. A good death does not just happen. I am far more likely to succumb to the attenuated fog of Alzheimer's than to collapse from a massive heart attack on the golf course – especially since I have no aptitude for the game.

In my research, I travelled to a death clinic in Switzerland, visited with doctors in the Netherlands and Belgium who regularly perform euthanasia, read reams of statistics exploding the myth of the slippery slope from countries that allow some form of physician-assisted death, and debated methodology and protocols with foes on either side of the dying spectrum from around the world.

And I travelled back in memory to my mother's protracted death in the early 1980s in a Montreal hospital. She spent nine weeks in an acute-care bed until her robust heart finally stopped beating in her cancer-ravaged body. At the time, I thought she died peacefully, with three of her children and her husband clustered around her bed holding her hand and rubbing her back while we waited out the pauses until her

agonal gasps finally stopped. Now I know we can do death better.

I don't want to linger nearly so long as my mother did, putting my family, the health-care system or my moribund self through a tortuous and expensive demise. Nor do I want to keep my illness – if I have one – a secret. My mother fought her cancer ferociously for more than a decade, guarding it close to her compromised breast. We never talked with her about hopes or fears, a choice I have seen friends make since. I hope I won't do that, because I know how hard a burden it places on partners and children.

A good death will not just happen. I need to make decisions and choices and share them with my family, my doctor and my lawyer. Knowing is not the same as doing, of course, but here's a start: I want to die in my own bed with a potion or an injection, after a final gathering of my closest family and friends. I'm still thinking about music and poetry and whether I should have a cat snuggled against my knees, but you get the idea. It is straight out of a Victorian melodrama, before technology and pharmaceuticals turned that roseate dream about the shutting down of the light into a noxious nightmare.

Death is the final mystery. It catches most of us unaware, which is probably why we fear its approach. So I've made a list of my death fears in descending order: dementia, ALS, Parkinson's or another neuro-degenerative disease, cancer.

Why, I wonder, is the death I fear the least getting the most attention from politicians, not to mention the caring professions? Even a terminal diagnosis usually gives you time to make out your will, assign powers of attorney for health and property, write your own death notice (leaving out the tricky bits), decide if you want a funeral or a memorial service, how much it should cost, who should speak and at what length.

The answer is simple: Cancer follows a predictable trajectory. You get a diagnosis, you undergo treatment, you are cured, or you go into remission until the cancer resurges and you die either in palliative care or with physician-assisted death as soon as your death is "reasonably foreseeable." That is why Bill C-14 does not mark the end of the campaign for our final human right – choice in timing and manner of our deaths. It is merely another frustrating stage in a long battle that began nearly 25 years ago, when Sue Rodriguez, who was suffering from ALS, famously asked, "If I can't give consent to my own death, whose body is this? Who owns my life?"

Now, there was a woman with heart.