The big picture

How education can be a lifeline for Syrian families

by Caroline Alphonso and Simona Chiose

About half of the refugees who have arrived in Canada from Syria have only a high-school education. Others lack proof that they completed higher education or must find a way to validate degrees from a country plunged into conflict. If they have their credentials, they must often upgrade them to meet the accreditation requirements of professional bodies here, or face working in jobs for which they are overqualified.

In these situations, younger generations who attend school in Canada become an immediate lifeline for their families. Students from Syria are different from refugees from other countries in that many still have family and friends left behind.

"To an extent, there is pressure to support the families who are still in a refugee camp or in Syria," said Michelle Manks, co-ordinator of the student-refugee program for World University Service of Canada.

So far, Canada has not had to plan for or accommodate the large-scale education issues faced by Germany, where hundreds of thousands of refugee students are expected to arrive within a year or two, or Sweden, where tens of thousands of people under 18 have come alone.

The demand for Canada's refuge may grow if the United States cuts foreign aid or reduces the number of refugees it accepts, as president-elect Donald Trump has stated he would do, Ms. Manks said, echoing warnings from other international refugee groups.

"The United States is the biggest funder by far of the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees," she said. "If Trump makes changes to that, it will have a huge impact on refugee protection around the world."

Should the number of refugees enrolling in elementary, high-school and postsecondary education increase, the programs currently in place provide one model for what works and the scale of the investment needed.

Elementary school

The early years: How school boards are helping Syrians start over

by Caroline Alphonso

When she arrived at Malvern Junior Public School in April, Elham Nanaa could only communicate with her teacher by typing Arabic into Google Translate.

FRED LUM/THE GLOBE AND MAIL

Elham Nanaa is planning a birthday party for her elementary-school teacher and she's drafted a reporter and a photographer visiting the classroom to do her bidding. "I need you to take Ms. Simos out of the room," she whispers.

She and her classmates, mostly Syrian refugees, string up balloons and set up a table with chocolate cake, chips, popcorn and pop, all the necessary elements for a celebration despite their families' generally modest means. "Surprise!" they yell as Niki Simos, the English-as-a-second-language teacher, enters the room.

Elham smiles and hugs her teacher, showing no trace of the shy little girl who entered Room 100 at Toronto's Malvern Junior Public School in April and could only communicate with Ms. Simos by typing her Arabic words into Google Translate.

Elham, 8, is among thousands of refugee children welcomed in schools across the country over the past year. The Toronto District School Board, Canada's largest school district, received about 800 Syrian refugee children.

How this eight-year-old Syrian refugee is learning English in a new land

There have been issues. Teachers' unions and boards have complained of the lack of provincial and federal funding as they discover the kind of needs the children may require, ranging from language resources to teacher assistants. In some instances, Canadian educators are teaching children who are attending school for the first time after leaving camps in the Middle East. Many school boards have had little choice but to tap into their own budgets to help these students.

"They are a special group of kids, so we want to give them a strong start to school," says Christine Oliver, supervisor of English language learning for the Calgary Board of Education.

The Calgary board has welcomed about 500 Syrian refugee children. Many of them enter a specialized program that puts all refugee students in smaller classes with a focus on English-language proficiency. Teachers also look for signs of trauma so that necessary supports are provided before the students attend regular classrooms.

At the TDSB, Marcia Powers-Dunlop, senior manager of professional support services, says schools do as much as they can with ESL supports.

"You have a bunch of children coming into the system that are not used to sitting still … some have anxiety, some have been traumatized," Ms. Powers-Dunlop says. "We've had a big learning curve."

She adds: "When all is said and done, I think we've done a good job with what we have."

In many ways, Elham is the poster child for the school board's success.

When Elham was four years old, she and her parents, three sisters, two brothers and grandmother left Aleppo. The Civil War had begun, and Elham's father, who owned a supermarket, wanted to keep the family away from the violence.

They travelled across the border to Turkey, and lived there for four years. Elham attended school in Turkey, one designed to house only Syrian children.

The family was sponsored by the Canadian government and arrived in the country in February. Unlike many other Syrian schoolchildren, Elham's education was not interrupted.

"I was excited," Elham says about coming to Canada. But "I was sad because I'm leaving my friends."

Ms. Simos, Elham's ESL teacher, remembers Elham on that first day. She was shy, but had a bright smile on her face, she recalls.

"You could tell she was excited to be here and was ready to learn," Ms. Simos says. "She just integrated into the classroom right away. She has confidence and I think that really helped her to adapt to the classroom routines."

Elham and her older brother, Ali, spend their mornings in the ESL classroom. She returns to her Grade 3 regular classroom in the afternoons.

The ESL classroom is an active atmosphere. Ms. Simos teaches nine students, seven of whom are Syrian refugees. She's patient around the students. She gently corrects their language and assists them in sounding out words.

She had challenges early on, helping them establish routines and teaching them about consequences to their behaviour. Some of them, Ms. Simos says, lived in refugee camps and did not necessarily attend school.

"Yes, the learning is important. But it's about feeling safe. They need to know that you care," Ms. Simos says.

Elham says her favourite activity is writing and reading in English. She could barely do either when she first arrived earlier this year. Ms. Simos and Elham conversed on an iPad using Google Translate.

"The [English] words started coming right away," Ms. Simos says. "I would say in the first few days. She picked up on the language right away."

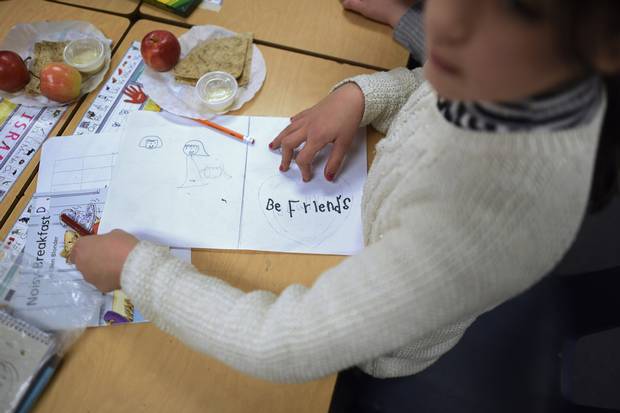

On a Wednesday morning, the students move from reading time on the carpet to choosing their own books to making posters.

One girl asks Ms. Simos how to spell "share." The teacher tells the girl to sound out the first two letters.

"C H," the girl responds.

"S H," Elham says from across the room.

Ms. Simos says that Elham's progress with her English-language skills may mean that she won't have to attend a self-contained ESL class next year. She will still need support from a specialized teacher, but not as intense.

"She's eager to learn. I see how well she's doing every day and I'm so amazed," she says. "She's speaking in full sentences – and they make sense."

Elham says her favourite activity is writing and reading in English.

FRED LUM/THE GLOBE AND MAIL

University

On their own: How Syrian families face tough choices on campus

by Simona Chiose

Sara Kuwatly, 21, is studying biology at the University of Guelph.

MARK BLINCH FOR THE GLOBE AND MAIL

Many mothers would like to have a daughter like Sara Kuwatly. Every weekend, Ms. Kuwatly, a 21-year-old studying biology at the University of Guelph, makes time to Skype with her mother in Norway. They talk for hours, catching up on everything they had not covered by text during the week.

Some of what they talk about are the usual concerns of any undergraduate. How she will prepare for multiple exams this month while holding a part-time job, her housemates, how to enjoy winter in Guelph, Ont.

But much of their conversation is about grappling with a past that has disappeared from the physical world and whether that means the future is fragile too.

"If I learned anything from the past five years it is to never plan something, because something always happens and it destroys your plans," said Ms. Kuwatly. "I just want to finish my four years and we will see what happens once I finish."

A Syrian, Ms. Kuwatly arrived in Canada from a temporary home in Lebanon last January, one of 76 students from Syria who came here through a long-running program from World University Service of Canada (WUSC), a non-profit development group. Since 1978, WUSC has resettled more than 1,500 young refugees, matching them to university and college programs across the country.

Last year, in response to the national campaign to resettle civilians fleeing from the five-year-long conflict, the program doubled its usual intake of students, largely a result of dozens of universities taking more students than ever before.

The program hopes to maintain that growth and double it again within five years. But it has not been easy to maintain the momentum.

"So far, we may not be able to meet those placements," said Michelle Manks, the senior manager of the student-refugee program at WUSC. "We would like institutions that work with us already to look at increasing the numbers to the same levels they increased them last year," she said.

While tuition costs for each student are waived or reduced by the postsecondary institution they attend, the program relies on campus student volunteers to fund-raise for the first year of the new arrivals' living costs and to offer practical advice and social support.

"We know the relationship lasts for the duration of their studies and often for their lifetimes," Ms. Manks said.

Every refugee has slightly different needs. For students from Syria, many of whom still have family or friends in the country, dealing with homesickness has been one of the biggest struggles.

"The homesickness is hard for us too," said Carly MacArthur, the co-ordinator of the student group at Guelph. "Those are the kind of things that we can't fix necessarily."

Sara Kuwatly: ‘If I learned anything from the past five years it is to never plan something, because something always happens and it destroys your plans.’

MARK BLINCH FOR THE GLOBE AND MAIL

For Ms. Kuwatly, arriving alone, in the winter of a quiet, small-town campus, the loneliness was acute.

"I am so attached to my family, that having to live away from them was so hard," she said.

She had grown up in a close family of five, who commuted to work and school from a suburb of Damascus. But after participating in demonstrations in 2011, her father – an accountant and small-factory owner – and her brother were both detained. Later, a friend of her mother's was arrested.

"When people decided that they want to fire back at the government, and all these countries got involved, that's when everybody realized there is no way back," Ms. Kuwatly said.

For her family, there was no choice. They would not become people "who have guns and go around shooting people," she said. An older brother was wanted by the regime.

Like millions of other Syrian refugees, they scattered.

Her father and a brother made their way to Germany, boarding a refugee ship. With her mother and a sister, Sara lived in Beirut. In the last year, her mother was resettled in Norway as a UNCHR-sponsored refugee; her sister is now in Germany.

A younger brother is still inside Syria. He is 17.

It could be years before the family threads unravelled by the conflict can be woven back, Ms. Kuwatly says.

And then, it is not clear where they would all be reunited. Lebanon does not allow those who leave as refugees to visit. Any return to Syria, even temporary, is a long way in the future. The building where they last lived was destroyed by bombing.

"I left knowing that I might not see my family again for four years, until I have Canadian citizenship or another citizenship – or until I can sponsor them to come here."

Still, when she talked to her mother in her loneliest early days in Canada, all she heard was encouragement.

"My mom just kept reminding me of what a great opportunity I had and that it might never happen again," she said.

As part of the student-refugee resettlement program, each student is matched to possible jobs on campus. That's how Ms. Kuwatly found a part-time position at the library, made friends and caught up with her academics.

Her English is almost flawless, picked up from listening to American music and watching English-language shows for most of her childhood. Because she only attended university in Beirut briefly, she is now in first year, a fact that annoys her.

"I'm 21. All my friends are graduating."

But the war means that she keeps in touch with old high-school friends only sporadically on Facebook.

"I know where they are and I know that they are safe but we are not that close any more," she said.

Since she has been in Guelph, Ms. Kuwatly has gotten to know another Syrian student who arrived with a sister, one sibling attending Guelph and another at the University of Waterloo. A privately sponsored family lives not too far away.

"Before I did it, I did not know that I can survive living away from my family," she said.

COLLEGE

The speedier solution for refugees who need work now

by Simona Chiose

If refugees are to succeed once they are resettled, they must be able to access education quickly. And while university degrees may be the solution for those who had to abandon postsecondary studies either in their home countries or in refugee camps, for others, colleges and the shorter programs they offer could be a better option.

"The short duration of college programs allows people to join the labour force much faster and it's where a lot of employment is," said Michelle Manks, the co-ordinator of the student-refugee program for World University Service of Canada.

College programs may also have more flexible admission requirements, which could help increase the number of young women who participate. In refugee camps in Kenya or Malawi, girls face more barriers to completing high-school education, whether it's doing chores or caring for siblings, Ms. Manks said.

"If families have to choose where to put limited resources, they prioritize the education of their young men," she said.

As a result, WUSC is planning to grow the program primarily by appealing to colleges and (in Quebec) CEGEPs to either start or increase their refugee placements.

Several colleges have already ramped up their programs for student refugees as well those living in neighbouring communities.

Algonquin College: Years of living in refugee camps or not having access to regular health care have left some refugees with neglected dental issues. At Ottawa-based Algonquin, dental hygienists, assistants and dentists offered a free dental clinic this summer. George Brown is now mounting a similar effort in Toronto.

Centennial College: The college in Scarborough, Ont., is combining help for Syrian refugees wanting to take courses there with assistance for elementary-school students. This week it will donate 50 backpacks filled with school supplies, warm clothing and gift cards to 50 Syrian refugee children in Toronto. And for one year, 10 Syrian refugees can receive waivers toward tuition starting next fall.

George Brown College: The college is offering workshops in Arabic as well as English on how to apply for postsecondary studies, where to take language courses and how to decide on and find pathways that match refugees' prior experience with what they want to do in Canada.

Seneca College: Ten Syrian refugees will be able to attend Toronto's Seneca College free, regardless of which program they choose, from a full-time, multiyear program to a short diploma.

MORE FROM THE GLOBE AND MAIL

’God has compensated me’: Manitoba town helps refugees make new lives