The military ceremony honouring Corporal John Unrau was bittersweet for his family.

After working in the army for two decades and deploying to Bosnia and Afghanistan, Cpl. Unrau, 42, was in chronic pain and suffering from post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) when he ended his life on Canada Day in 2015. On Oct. 26, before the soldier's family, friends and co-workers, the Canadian Armed Forces recognized that his suicide was connected to his military service, presenting the Memorial Cross medals to his mother, Dorothy, and his brothers, Eddy and Dan, at the Sudbury Armoury in northern Ontario.

The Sacrifice Medal was also posthumously bestowed on Cpl. Unrau, who was part of the Lord Strathcona's Horse armoured regiment in Edmonton.

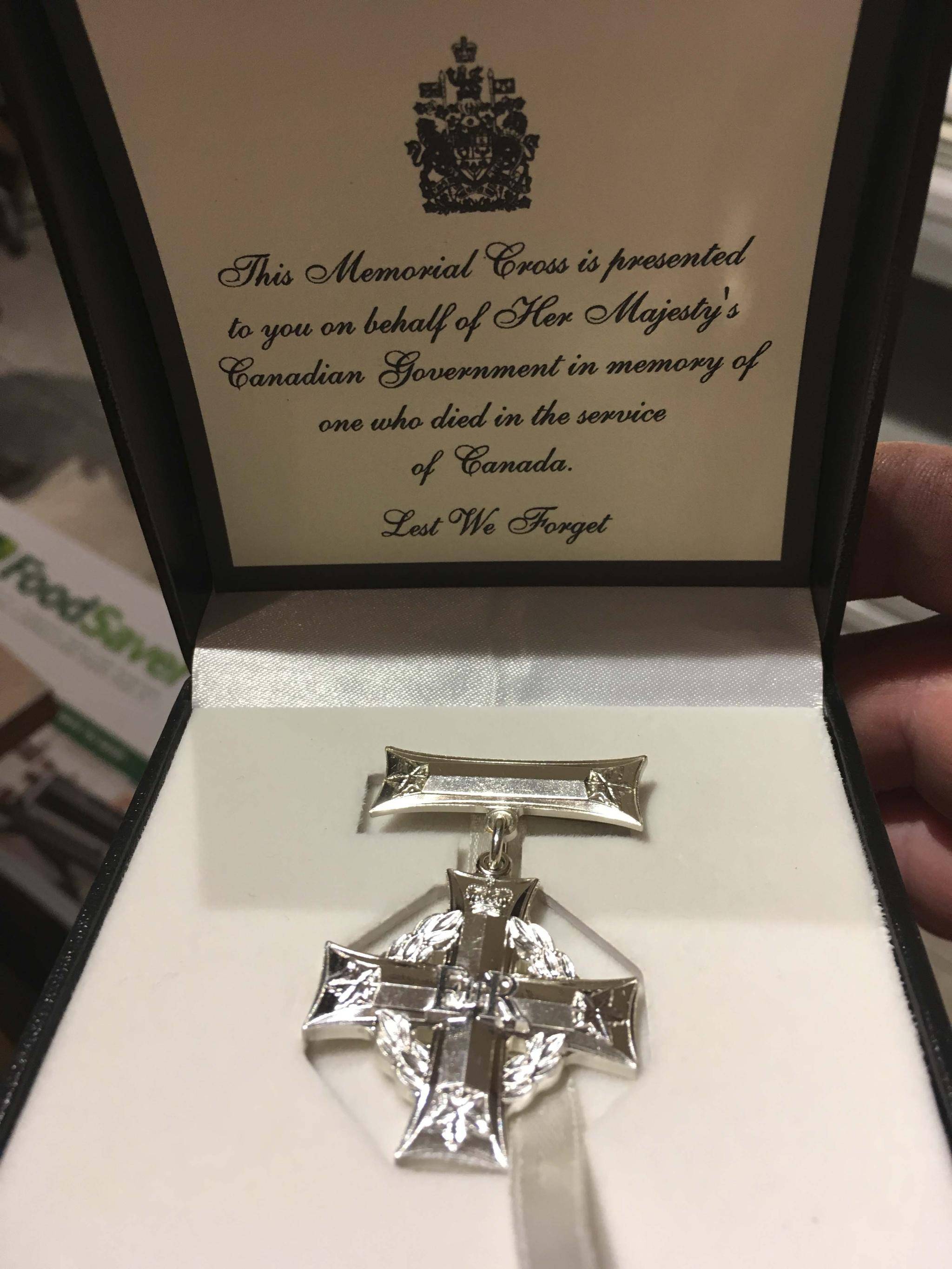

The Memorial Cross and ribbons are awards given to the loved ones of Canadian Armed Forces personnel who died in service or whose death was attributed to their service, and the Sacrifice Medal recognizes those who die as a result of military service or are wounded by hostile action.

For his family, the official acknowledgment meant that Cpl. Unrau would be recognized as a casualty of the Afghanistan war, along with the 158 soldiers who died during the mission.

"They've accepted it. That's all we wanted," Eddy Unrau said. "Just don't say [the suicide] had nothing to do with being in the military, because that's why Johnny did this – entirely because of the military."

Cpl. Unrau is one of more than 70 Canadian soldiers and veterans who served in the Afghanistan operation and later took their own lives, a continuing Globe and Mail investigation has revealed. The newspaper told the stories of 31 of these fallen soldiers last fall, examining the factors that may have contributed to their deaths, including battlefield trauma, mental illness, relationship strife and financial troubles.

Lisa McBain places a candle for her late brother Corp. John Unrau during a candlelight ceremony to honour the memory of Soldiers of Suicide (S.O.S.) at the National Military Cemetery of the Canadian Forces at Beechwood Cemetery Feb. 21, 2017 in Ottawa.

DAVE CHAN/THE GLOBE AND MAIL

Many were severely affected by their experiences in the war. But The Globe's investigation found that only eight of their families had been awarded the Memorial Cross and Sacrifice Medal, even though a death by suicide is supposed to be treated no differently than a death on deployment or in domestic operations.

The Forces began a review as a result of the newspaper's inquiries. Fifteen families have now been given the recognition, while another dozen are expected to receive the honours soon, military spokesman Derek Abma said.

Four of the 31 cases remain under review.

The father and sisters of Sergeant Doug McLoughlin are still waiting to hear whether the long-time Edmonton infantry soldier will be honoured. Diagnosed with PTSD after deploying twice to Bosnia and twice to Afghanistan, Sgt. McLoughlin, 37, was going to be medically released from the Forces when he took his life in March, 2013.

A military board of inquiry determined in 2014 that his suicide was connected to his army service, according to a partly redacted report The Globe obtained under access-to-information legislation. The report noted that Sgt. McLoughlin went on three overseas tours from February, 2000, to April, 2002, with only short breaks between the difficult deployments.

His father, Brendan McLoughlin, who served in the British Army, said the wait for his son's honours has been difficult. His son was a member of the 1st Battalion of the Princess Patricia's Canadian Light Infantry.

"It's disappointing for me a little bit that we haven't received anything yet," Mr. McLoughlin said. "The medals would be recognition from the military that he did serve his country well."

Anita Cenerini and her family waited 13 years for her son, Private Thomas Welch, to be recognized. The young trooper was the first Canadian soldier to take his own life after returning from the Afghanistan war.

A 22-year-old rifleman with the 3rd Battalion of the Royal Canadian Regiment in Petawawa, Ont., Pte. Welch had been back from Afghanistan for less than three months when he ended his life on May 8, 2004, just hours before he was supposed to board a flight for Thunder Bay, Ont., to be with his family on Mother's Day.

Anita Cenerini holds a portrait of her son, Private Thomas Welch, at her Winnipeg home in October 2016, with Pte. Welch’s stepfather, Grant Palmer, left, and brother, Jacob Cenerini-Palmer, right. In 2004, Pte. Welch, suffering from post-traumatic stress disorder, died by suicide three months after returning from Afghanistan.

LYLE STAFFORD/THE GLOBE AND MAIL

Yet no military board of inquiry was held to examine the circumstances that may have contributed to his suicide and whether his death was connected to his Afghanistan tour.

After The Globe published a report on the troubling case in the spring, military officials met with Ms. Cenerini. She told them about her son's mental-health struggles during and after his deployment. She suspected he was grappling with PTSD.

Soon after the meeting, Pte. Welch's death was reclassified. The Department of Veterans Affairs affirmed that the soldier's suicide was linked to his Afghanistan tour.

Ms. Cenerini said she finally felt at peace. Her fight was over.

"It meant closure for me because it gave me peace that Thomas's death was not in vain," she said. "There is recognition and acknowledgment that he died as an honourable member of the military and his death was attributable to his service in Afghanistan, which is something that I always knew in my heart. That was never a question for me."

A private memorial service was held on Sept. 18 at the military base in Petawawa to honour Pte. Welch. Brigadier-General Stephen Cadden, commander of 4th Canadian Division, presented Ms. Cenerini with her son's Sacrifice Medal. Ms. Cenerini also received the Memorial Cross, and her husband, Grant Palmer, and their son, Jacob, were given Memorial ribbons.

After the medal ceremony, Brig.-Gen. Cadden spoke for some time with Ms. Cenerini.

"The love and pride which she still so evidently feels for Thomas made me very glad that this recognition, although delayed, has been made, so that her country is just as proud of him," Brig.-Gen. Cadden said in an e-mail. "To those of us in uniform, we have a duty to remember the fallen, to acknowledge their sacrifice, and to honour their memory."