Out the bubble window of a surveillance plane in the middle of the Gulf of St. Lawrence, a North Atlantic right whale surfaces from a dive for plankton and reveals fresh pinky orange welts on its tail. It's a depressing and too familiar sight for the four biologists on board who have been observing and recording the whales over the last six weeks.

At least 10 right whales have been found dead in the Gulf of St. Lawrence this summer and the death toll could reach as high as 12 depending on the results of genetic testing to confirm the whales' identities. The deaths represent about 2.5 per cent of the critically endangered right whale population, of which there are only about 525 left in the world.

"It's devastating to the species of North Atlantic right whales," said Moira Brown, a right whale scientist with the Canadian Whale Institute and the New England Aquarium. "We're all shocked by this."

Right whales have been popping up in summer months since at least 2010 in the Gulf of St. Lawrence, a semi-enclosed fishing and shipping area bordering the Atlantic provinces and Quebec. Historically, the whales like to feed in the Bay of Fundy and Roseway Basin off southern Nova Scotia in summer, but recent aerial surveys show an unprecedented number – 80 to 100 – are hanging out in the Gulf of St. Lawrence.

Scientists believe they're travelling further north for food: each day in summer these school-bus sized mammals like to eat 1,100 kilograms of high-fat, rice-sized zooplankton called copepods. They're bulking up for winter and reproduction.

North Atlantic right whale sightings,

July 3 to 31, 2017

Gulf of

St. Lawrence

Nfld.

Anticosti Island

Shipping lanes*

Whale sightings

Que.

Îles-de-la-

Madeleine

PEI

N.B.

N.S.

Halifax

Atlantic

Ocean

Bay of

Fundy

Grand

Manan Island

Roseway

Basin

0

150

KM

*More than 50 ships per year

North Atlantic right whale migration route

Que.

N.B.

Feeding grounds

Me.

Summer/fall

Winter/spring

Mass.

N.Y.

Spring/summer

Pa.

Migration route

Va.

N.C.

S.C.

Calving grounds

Atlantic

Ocean

Fall/winter

Fla.

0

300

KM

MURAT YUKSELIR / THE GLOBE AND MAIL, SOURCE:

NOAA; SMITHSONIAN OCEAN PORTAL

North Atlantic right whale sightings,

July 3 to 31, 2017

Gulf of

St. Lawrence

Nfld.

Anticosti Island

Shipping lanes*

Whale sightings

Que.

Îles-de-la-

Madeleine

PEI

N.B.

N.S.

Halifax

Atlantic

Ocean

Bay of

Fundy

Grand

Manan Island

Roseway

Basin

0

150

KM

*More than 50 ships per year

North Atlantic right whale migration route

Que.

N.B.

Feeding grounds

Me.

Summer/fall

Winter/spring

Mass.

N.Y.

Spring/summer

Pa.

Migration route

Va.

N.C.

S.C.

Calving grounds

Atlantic

Ocean

Fall/winter

Fla.

0

300

KM

MURAT YUKSELIR / THE GLOBE AND MAIL, SOURCE:

NOAA; SMITHSONIAN OCEAN PORTAL

North Atlantic right whale sightings, July 3 to 31, 2017

Gulf of

St. Lawrence

Nfld.

Anticosti Island

Shipping lanes*

Whale sightings

Que.

Îles-de-la-

Madeleine

PEI

N.B.

N.S.

Halifax

Atlantic

Ocean

Bay of

Fundy

0

150

Grand

Manan Island

KM

Roseway

Basin

*More than 50 ships per year

North Atlantic right whale migration route

Que.

N.B.

Feeding grounds

Me.

Summer/fall

Winter/spring

Mass.

N.Y.

Spring/summer

Pa.

Migration route

Va.

N.C.

S.C.

Calving grounds

Ga.

Atlantic

Ocean

Fall/winter

0

300

Fla.

KM

MURAT YUKSELIR / THE GLOBE AND MAIL, SOURCE: NOAA; SMITHSONIAN OCEAN PORTAL

North Atlantic right whale

Sightings, July 3 to 31, 2017

Migration route

Gulf of

St. Lawrence

Que.

Nfld.

Anticosti Island

Shipping lanes*

N.B.

Feeding grounds

Whale sightings

Me.

Summer/fall

Que.

Îles-de-la-

Madeleine

Winter/spring

Mass.

N.Y.

Spring/summer

Pa.

PEI

N.B.

Migration route

N.S.

Va.

N.C.

Halifax

Bay of

Fundy

S.C.

Atlantic

Ocean

Atlantic

Ocean

Calving grounds

Fall/winter

Grand

Manan Island

Roseway

Basin

0

150

0

300

Fla.

*More than 50 ships per year

KM

KM

MURAT YUKSELIR / THE GLOBE AND MAIL, SOURCE: NOAA; SMITHSONIAN OCEAN PORTAL

On board the joint U.S. and Canadian government-funded surveillance mission, biologists are laying the groundwork to help protect the right whales in the Gulf. They've been up in the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration Twin Otter aircraft since mid-June, circling and swooping to map and photograph the whales. The data will provide information on where the whales are, how many, for how long and why. It will be shared with governments, scientists and the New England Aquarium, which keeps a catalogue on all right whales known to be in existence.

On board the flight, Jen Jakush, a biologist with the Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission, calls out descriptions of each whale's callosity pattern as its massive black body surfaces. Callosity refers to unique calcified skin patches on a whale's head that identify it, much like facial features. Ms. Jakush is an expert in this area and recognizes the whales' faces and knows their names, catalogue numbers and family trees by heart. Another biologist points a long lens camera linked to GPS out the aircraft window to capture them.

The biologists – two from the U.S. government's Northeast Fisheries Science Center in Massachusetts, one from Fisheries and Oceans Canada in Halifax and Ms. Jakush – are bonded by their fascination for this mammal, which takes them up and down the North Atlantic coastline. This summer has been difficult as they've watched the whales drop off in large numbers.

They say the whales don't look good in the Gulf; many are thin and beat up with lesions. They spotted four entangled in fishing gear up here. And then there are the 10 deaths.

Necropsies on six of the dead whales have been done and early results show three died from blunt force trauma from ship collisions and one died from fishing gear entanglements. Full results are expected mid-September.

A ship tows a dead whale near Norway, PEI. At least 10 North Atlantic right whales have been found dead in the Gulf of St. Lawrence this summer.

DEPARTMENT OF FISHERIES AND OCEANS

Dr. Pierre-Yves Dumont collects samples from one of the dead right whales. Several of the whale deaths have been attributed to entanglement in fishing gear or strikes from vessels.

MARINE ANIMAL RESPONSE SOCIETY/THE CANADIAN PRESS

In Shippagan, N.B., a whale carcass lise on the beach after a necropsy.

MARINE ANIMAL RESPONSE SOCIETY

There are only 524 North Atlantic right whales left in the world.

MARINE ANIMAL RESPONSE SOCIETY

On a Prince Edward Island beach on June 30, experts dissect and haul away a right whale carcass. Necropsies and aerial surveillance data are helping to inform fisheries authorities about how more whale deaths can be prevented.

MARINE ANIMAL RESPOSNE SOCIETY

Right whales in the Gulf of St. Lawrence are a predicament that pits the survival of the species against major economic drivers in the region. The area is a commercial shipping freeway and an important North American trade corridor that handles 40 to 50 million annual tons of cargo. It's also home to a lucrative fish and seafood industry valued at $467-million annually.

The reason why they're here may be tied to climate change. Scientists have published studies that show the Gulf of Maine is warming faster than any other part of the North Atlantic Ocean. Dr. Brown said scientists are looking at concentrations of plankton and ocean currents to see how this may be affecting the whales' food supply.

On this last day of aerial surveillance, a right whale surfaced with raw peach-coloured scars on its tail, which Ms. Jakush said was likely caused by trailing fishing line days to weeks ago.

She said right whales generally get the rope in their mouth first and then it gets entangled around their head and body. As they swim, the lines chafe their skin and drain their energy. The lines can slice through their blubber, which can lead to infection and a slow, drawn-out death.

Eighty-three per cent of the North Atlantic right whale population bears scars from entanglements, according to the New England Aquarium and the Center for Coastal Studies. Twenty-seven per cent have scars from multiple entanglements. Some animals have been entangled as many as six or seven times.

Tim Cole, a U.S. government research biologist with the Northeast Fisheries Science Center on board the flight, explained how the fishing gear depletes the animal: "A whale swimming normally uses the energy equivalent of 16 people on a treadmill but if you start putting lines and buoys on it, the energy requirement goes up and over time it's a drain," he said.

DFO marine biologist Angelia Vanderlaan said data from the aerial surveillance was used by Fisheries and Oceans Canada in its decision to suspend and later close the snow crab fishery in the southern Gulf of St. Lawrence on July 20.

On the July 29 surveillance flight, however, several fishing buoys could still be seen in the Gulf near the whales. Fisheries and Oceans Canada said in a statement that it's "actively monitoring the waters from the air and sea, scanning for fishing gear, and taking action to remove abandoned gear when need be."

On Friday, the federal government added stricter temporary measures to prevent more right whale deaths in the Gulf, ordering large vessels to slow down to 10 knots. If ships don't comply with the rule, which will be enforced by Transport Canada and the Canadian Coast Guard, they could be fined up to $25,000.

The Canadian government also requested that mariners be on the lookout for right whales and voluntarily reduce speed along the Laurentian channel in shipping lanes between the Magdalen Islands to and the Gaspé peninsula until Sept. 30 when many the whales migrate to coastal Florida and Georgia for the winter.

Chris Taggart, an oceanography professor at Dalhousie University, says slowing down isn't the best solution and only lowers the kill probability to 50 per cent.

Prof. Taggart, principal investigator for a whale habitat and listening experiment that's part of Dalhousie's Marine Environmental Observation, Prediction and Response Network, said the way of the future to protect right whales from ship strikes is acoustic sound technology or a real time alert system for mariners, which Dalhousie has been using in the Gulf since last year. (The federal government contributed $56,000 towards the project.)

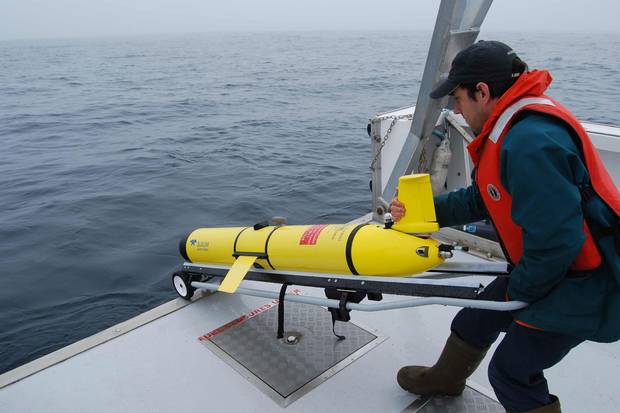

The project uses gliders, which are like small submarines with wings. They zigzag through the ocean and record whales' sounds to identify their location and then alert ships if whales are in their path.

"It's 24/7 and it's weather independent," said Mr. Taggart. "They can send the data in real time and from a cost perspective, they're dirt cheap. It puts no humans at risk."

Researchers use gliders to track the whales and give vessels information on their locations to avoid strikes.

OCEAN TRACKING NETWORK

Mr. Taggart and Dr. Brown helped change shipping lanes in the Bay of Fundy in 2003 and created a voluntary avoidance area for ships in the Roseway Basin in 2008 to protect right whales. Ongoing studies show these efforts lowered the risk of ship strikes by 90 per cent and 82 per cent, respectively. After that, the right whale population had rebounded by about a third.

But now right whales are on the decline.

Only five calves were born this year, compared to 14 in 2016, according to the New England Aquarium. From 2000 to 2016, an average of 19 calves were born each year. Dr. Brown said if right whales are travelling farther to find food, it can cause stress and compromise their health and subsequent birth rates.

"Any of our cautious optimism that this species was on its way to recovery has been erased," said Dr. Brown from her home on Campobello Island, N.B., adding that she's overwhelmed and exhausted from the loss. She also points out that one died in the Gulf in 2016 and three more in 2015.

"If this level of mortality is not prevented, right whales are headed for extinction."

Minister of Fisheries, Oceans and the Canadian Coast Guard Dominic LeBlanc said this month that this situation in the Gulf poses a challenge and he's already been looking at measures to better protect the right whales – from changing the types of fishing gear, mandatory reporting of the sighting of right whales and using acoustic sounding technologies to better track them. "A whole series of things are going to be in place in the coming weeks as the whales migrate out of the Gulf of St. Lawrence," he said.

"At the end of the day the government of Canada will take its responsibility under law to protect this species.

"I'm not prepared to have a circumstance like the one we had this year repeat itself next year."

THE DEATH TOLL

North Atlantic right whale deaths in the Gulf of St. Lawrence in 2017

A dead North Atlantic right whale is shown in the River of Ponds area in western Newfoundland.

FISHERIES AND OCEANS CANADA/THE CANADIAN PRESS

1. Ten-year-old male (catalogue #3746) was spotted dead in the south central area of the Gulf of St. Lawrence on June 6. He was last seen alive April 23 feeding in Cape Cod Bay. This was the first time he had been seen in the Gulf.

2. "Glacier," named for the large white scar on his back, was a 33-year-old male spotted in the south central area of the Gulf of St. Lawrence on June 19. He was last seen in the Gulf on July 29, 2016.

3. "Panama," a 17-year-old male, was located June 18 in the south central area of the Gulf of St. Lawrence. He was last seen alive Feb. 14 feeding in Cape Cod Bay. He fathered at least one calf in 2011.

4. "Starboard," an 11-year-old female named after her severed right fluke, was spotted dead June 22 in the south central area of the Gulf of St. Lawrence. She was tangled in fishing gear and had rope through her mouth and right flipper.

5. Unidentified female carcass found in the south central area of the Gulf of St. Lawrence on June 22.

6. A 37-year-old male (catalogue #1207) carcass was found fresh with blood coming from his genital region in the south central area of the Gulf of St. Lawrence on June 23. He fathered at least two calves in 2005 and 2008.

7. A non-identified male discovered dead July 5 in the Gulf of St. Lawrence near the Magdalen Islands.

8. "Peanut," a 26-year-old male named for shape of a scar on his head, was spotted dead July 19. He had fathered at least one calf in 2004.

9. An unidentified right whale washed up on the shores of Trout River in western Newfoundland on July 21.

10. An unidentified right whale washed up near Cape Ray in western Newfoundland on July 27.

Two more unidentified right whales washed up on the shoreline of western Newfoundland: one on July 27 near Lark Harbour and another on July 30 south of the River of Ponds, meaning it's possible, if they are not are matches with number 1 and 5 above, that the list of deaths could grow to 12.

Sources: New England Aquarium and Marine Animal Response Society

Video: Studying right whale carcasses to discover what’s causing their deaths

SAVING THE WHALES

Risks for the rescuers

Joe Howlett of the Campobello Whale Rescue Team, right, works from the bow of a boat disentangling endangered right whales. Mr. Howlett died in July when a whale he had just freed struck his boat with its tail.

NEW ENGLAND AQUARIUM

The dangers associated with rescuing a whale trapped in fishing gear hit home last month when Joe Howlett, a lobster fisherman and veteran volunteer whale disentangler, died while freeing a North Atlantic right whale off the coast of eastern New Brunswick.

"It's going to take a long time to learn to live with this one," said Moira Brown, a close friend of Mr. Howlett and right whale scientist with the Canadian Whale Institute and the New England Aquarium who had been on many whale rescues with him.

She got the call July 10 when Mr. Howlett, 59, was aboard a federal Fisheries Department vessel off Shippagan. He had just cut the lines from a right whale that was entangled in fishing rope when the whale hit him as it was cut free and swam away.

Fisheries and Oceans Canada responded by suspending its responses to entangled right whales while it reviews its policies and practices. The department says there are serious risks involved with any disentanglement attempt and that each situation is unique and whales can be unpredictable.

But there have been a lot of questions surrounding this decision: "This is not something Joe would've wanted," said Dr. Brown. "We are still ready to respond."

During entanglements, responders use a Zodiac rigid-hulled inflatable boat to approach the whale and cut the fishing lines using hook knives attached to poles. "We discuss our approaches," said Dr. Brown. "When we arrive at an entangled whale, we assess the entanglement. We assess the behaviour of the whale. We make very cautious approaches and if anybody doesn't feel comfortable they speak up. Everybody is just watching out for everybody else. Joe was great at that."

Rescuer Joe Howlett untangles a right whale in August, 2016

WHALES AND OUR WORLD: MORE FROM THE GLOBE