One year after the crash that killed 47 people and devastated its downtown, Lac-Mégantic remains haunted by the tragedy – its residents caught between the impulse to stay and rebuild and the desire to move on.

Christian Lafontaine moves through his day like a man in a hurry. He’s a survivor and, between expanded responsibilities with his family’s construction business and a one-month-old baby at home, the 46-year-old seems always to be thinking about the next thing to do, the next place to be. It’s as if, through constant motion, he can keep the past at bay.

Mr. Lafontaine and his wife, Melanie Guérard, were the last patrons to find their way out of the packed Musi-Café in Lac-Mégantic after a hurtling train crashed into the small Quebec town last year, killing 47 people and laying waste to several downtown blocks. Afterward, Mr. Lafontaine memorialized the escape on his right bicep: The shoulder-to-elbow tattoo shows the couple running away as flames engulf the café behind them; in the background lies the iconic Ste-Agnès church, surrounded by black tank cars thrown from the train.

He lost his brother, Gaétan Lafontaine, and Gaétan’s wife, Joanie Turmel, along with several close friends. It was a dreadful intrusion on the life his family had built just outside Lac-Mégantic, so entrenched that several residential streets bear his brothers’ and father’s first names.

Mr. Lafontaine says he has no plans to leave this picturesque region in Eastern Quebec, but he knows of others who have chosen to move, either out of frustration with the pace of reconstruction or because the memories of the accident are still too harrowing.

“Everyone has their reasons,” he says. “Everyone has their ghosts.”

One year after the horrific crash, Lac-Mégantic remains haunted by a tragedy that has touched nearly everyone in town. There is no escaping the ghosts of the dead in a now deeply scarred place working to put itself back together, one halting project at a time. Some, like Mr. Lafontaine, appear to have reached a sense of peace with what happened, even as they mourn those they’ve lost. Others are fighting a barely concealed battle against flashbacks, nightmares and relentless grief.

Thus the strange psyche of this traumatized town of 6,000: caught between the impulse to stay and rebuild and the desire to move on – between fight and flight. Looming, too, are questions about the thing Lac-Mégantic lost that seems most likely to return: the snaking trains laden with volatile crude oil that once rolled through the lakeside town.

‘A heavy burden’

Yannick Gagné stands by a steel skeleton on the edge of the new commercial district built adjacent to the shattered downtown. The owner of the Musi-Café, where more than half of the victims died on July 6, had planned to reopen the bar on a new site by the one-year anniversary. That reopening has now been delayed by months as he waits for financial aid long promised by governments in Ottawa and Quebec City.

When it eventually opens in September, the new Musi-Café will reflect the region that surrounds it, with furnishings rich in local wood and granite dug from the hills surrounding Lac-Mégantic. Mr. Gagné worries that, without aid, he may have about $600,000 in debts before he can open the bar.

“That’s a heavy burden,” he says. “We’ve had to fight to build this project and we aren’t done yet. This isn’t the same city any more – a lot is left to save, we’ve changed.”

His staff has scattered across Quebec. Karine Blanchette, an actress and waitress, now lives in Saint-Hyacinthe, near Montreal. She prefers not to talk about what happened last year.

The bar’s former manager, Sophie L’Heureux, has also left the region in search of work. With a smile, Mr. Gagné says he’ll convince her to come back once the bar has been rebuilt.

The railroad tracks run about a dozen metres west of the new Musi-Café construction site, the same distance as from the old bar.

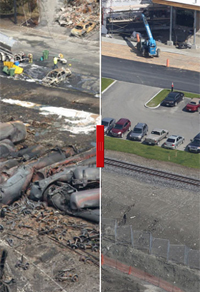

When driving downhill toward the community’s core, you now encounter a virtual trompe-l’œil as the buildings on quaint Frontenac Street are still standing in the distance and appear unmolested, almost deceiving you into thinking the rebuilding is over. Cresting a hill, you see the storm fencing, and mountains of dirt rush into sight. The downtown is still walled off.

While some of the tall storm fencing brought in by Quebec provincial police last summer is gone, most has been moved back nearer to the Red Zone, as it’s called, and the blackened rump of downtown. The black shroud that once hid the devastation from public view has been removed. The scar is now fully visible.

For many, the gash in the centre of town is a constant reminder of the tragedy and makes it more difficult to move on.

“We are grieving events that still aren’t in the past, they are all around. In the normal process of grieving we regain the rhythm of life, however that rhythm is upended here. You see outside my window,” says Father Steve Lemay, gesturing at the scene of devastation outside his Ste-Agnès Church office. “You see, it’s the same for everyone, even the most banal of outings confronts us with grief.”

‘Inside, everything is moving’

A year ago, René Simard was smoking a cigarette on the terrace of the Musi-Café when the Montreal, Maine & Atlantic oil train careened into town. Many of the people closest to him were inside the bar, celebrating his friend Stéphane Bolduc’s birthday. Simard was an art teacher at the local high school for two decades, and most of the patrons were his students at some point.

Within moments he was running as the train derailed. He spotted his car parked nearby and ran toward it. The car exploded. He survived; his friends did not.

Now, most nights Mr. Simard sleeps on his couch, fully clothed, ready to run out of his house at any moment. He knows it sounds outrageous, but it helps him sleep.

Once clean-cut and conservatively dressed, he now wears a loose T-shirt and has grown a beard. He lives a Zen life, he explains inside his warmly decorated home.

Mr. Simard hasn’t returned to work since the accident and has been diagnosed with post-traumatic stress disorder. His friends now come to see him at his home in Nantes, on the outskirts of Lac-Mégantic. He lists his triggers: The orange lights on winter plows make his chest feel like it is being crushed; sirens are intolerable; sitting in the middle of restaurants causes panic attacks; he avoids being in crowds and tunes out the sound of yelling children.

Then there are the demons of night. “I’m always having nightmares, terrible nightmares. I’m like a child when I wake up. I’m killing my mother, doing terrible things,” he says. “This is crazy. I told my psychologist to lock me up in an iron jacket, but he told me that this is normal. A little girl was playing on her deck this morning and her screams made me go back to that evening, just talking about it makes my chest tighten. Her screams brought me back to the people I heard burn to death behind me.”

In fact, hundreds of locals are experiencing cases of serious trauma. In trailers behind the city’s hospital, 30 social workers are dealing with a deluge of new files. The number of locals seeking help increases weekly, along with the severity of the reported problems, according to town councillor André Desjardins.

On Oct. 31, a volunteer firefighter who worked at the town’s largest employer, Tafisa, died by suicide. The young man killed himself after losing his girlfriend in the disaster and spending the first hectic days in the fiery downtown, helping unearth the bodies of some of his closest friends.

“A volcano is still burning in the population,” says Tafisa CEO Louis Brassard, describing the man’s struggle and the impact it has had on the factory floor.

When Mr. Simard first met with The Globe and Mail in October, the skin on his hands was red, deeply cracked and swollen. He now has deep red streaks on his face. “Stress,” he says. “I look relaxed, but inside, everything is moving.”

What worries the artist most is his loss of creativity. He’s hung his art on his walls, but his past collages and paintings only seem to taunt him. The spark is gone. His impeccable French has also suffered and he now keeps a dictionary on his kitchen table.

To cope, he’s resurrected the dreams of his childhood. “My parents didn’t want me to have birds,” he says, “so I bought birds.” He now has five, most of them chatty parakeets.

He compares his grief to a set of Russian nesting dolls. Ten of his close friends were lost – too many to cope with collectively. Each death must be dealt with separately, each resolution leading to the next period of mourning.

In his closet, Mr. Simard keeps a mesh baseball cap that Mr. Bolduc used to wear when the two sailed on Mégantic Lake.

“I won’t wear the hat, I haven’t even adjusted it in the back,” he says. “It’s an object that I treasure.”

An exodus, real or imagined

Despite the trauma of the accident and the challenge of living in a town under constant reconstruction, many residents say their decision to stay was an easy one. Some cite their own families’ roots here, others point to the tightly knit nature of the community or the stunning scenery of Quebec’s Eastern Townships.

Sylvain Brier, the associate vice-principal at Lac-Mégantic’s high school, says that, because he only moved to Lac-Mégantic in late 2012, he doesn’t share the same history as some families in town. But, he adds, “It’s a small place so when somebody leaves it makes a big mark, you know, leaves a big trail behind. And they have lived here all their lives.”

Both the regional school board and the Lac-Mégantic high school say there has been no notable decrease in the student body and, while the municipality confirms a population decline, it has refused to provide any numbers.

Even lacking proof, many in Lac-Mégantic seem to feel that an exodus has started. Whether or not it is true – and many argue it isn’t – the departure of a few has left others wondering whether they should follow and escape what could be a decade of painful reconstruction.

A review of real-estate listings shows a large number of houses on the market. “There are a lot of homes that are for sale, an enormous number, maybe even more than last year,” says local real-estate agent Gina Dubé.

Ms. Dubé’s face is plastered on signs around Lac-Mégantic. She had a record year in 2013 as sales increased by 50 per cent following the disaster. “We were in a state of shock,” she remembers.

Nearly 100 businesses and residents suddenly found themselves homeless. While some would soon be allowed to return to their homes, much of the town’s centre is still off-limits and slated for demolition.

Along with the evacuees, Ms. Dubé says many of her listings are from local couples who split up after the tragedy. “It forced many people to re-examine their lives and put things in perspective; it’s sad, but many broke up,” she says.

Ms. Dubé says others have simply left Lac-Mégantic, although she hasn’t collected a number. She also says very few new residents have arrived.

“New people will come. We’re going to be a new city soon, that will entice people,” she says. “What has happened is that Lac-Mégantic has been discovered. The city had always been considered the rough diamond of the Estrie [the French name for the Eastern Townships], now people have learned of it.”

In the months following the tragedy, thousands of Quebeckers swarmed to the town to see the devastation. While derided by locals as “loiterers” and “lookie-loos,” many have come back several times to enjoy the beauty of the area.

While the disaster has encouraged some residents to leave, the migration has been reversed for others. Frédérike Simard, 22, is moving back to Lac-Mégantic to be closer to her father and her fiancé’s family.

“I almost lost my dad. That was a wake-up call, so I decided to move back and be near him,” she says.

A hairdresser in Quebec City, she’s emotional when describing the realization that her father escaped being a victim in Canada’s deadliest modern rail disaster by only moments – and because he borrowed a cigarette.

Her fiancé, Sébastien Bolduc, is happy to join her in the move. A soldier in the Royal 22nd Regiment in Quebec City, the Van Doos, Mr. Bolduc was injured in Afghanistan and is ending his time in the military.

“My family is important, I just wanted to be closer,” he says. He was the one with the dangerous job; he never expected his brother Stéphane would die in the cozy Musi-Café, surrounded by friends.

The smell of oil

The disaster was disorienting for everyone. “The problem here is that people lost their points of reference and now their daily routines are gone,” says Mr. Desjardins, the town councillor. “They used to go for walks in the evening and have their coffees in the morning; that’s all been disrupted.”

On Kelly Street, the paint is fresh on Robert Dallaire’s house. Only a few metres and a badly burned maple separate him from Veterans Park, where hundreds of thousands of litres of flaming oil flowed into Mégantic Lake.

The retiree moved back into the house as soon as permitted and went to work repairing the damage. He and his family made it clear they had no plans to go anywhere.

“There was no question that we were staying,” he says. He was away at the time of the disaster; many of his neighbours died while they slept.

When Mr. Dallaire’s wife finally saw what was left of the street where they lived for 25 years, he says, she had a “crisis.” She’s been mute ever since, diagnosed with post-traumatic shock and slowly relearning to speak.

The smell of oil can be almost intolerable in their home. Angry at a lack of information from the town and the slow pace of redevelopment, the couple will be travelling Quebec in an RV this summer.

‘A bitter taste’

Like many towns in rural Canada, Lac-Mégantic is entwined with the railway that runs through it. Founded as Mégantic in 1884, the town came into being just as the final stretch of the cross-Canada railway was constructed between Montreal and Atlantic Canada. It was renamed Lac-Mégantic in 1958 for the lake it sits beside.

Without the railway, residents are certain that the town’s biggest industrial employers would leave. But if the train comes back through town carrying oil – a real possibility after January, 2016 – others have declared they would choose to leave rather than live in fear of another tragedy.

“It’s paradoxical,” says Richard Michaud, a town councillor and long-time Lac-Mégantic resident. “The town was built with the railway, and then the town had its biggest disaster with the railway. So it leaves a bitter taste.”

The town’s struggling economy has not made things any easier. One councillor estimates that roughly 300 people are collecting employment insurance benefits and a total of 800 jobs were lost.

For one group of local business owners, the tragedy represents an important opportunity for renewal. The group, called Groupe Action Mégantic, is pressing for a new tourism plan aimed at capitalizing on the attention Lac-Mégantic has received since last year. The group has proposed building an Imax theatre and a 300-bed hotel, along with an interpretation centre that would describe Lac-Mégantic’s history, including the devastating rail accident.

Mr. Michaud, who is in charge of culture at the town council, says the region can continue to draw people with its stargazing and heritage. But when it comes to the old motto “From the railway to the Milky Way,” he’s certain that will change. “We’ll do away with the railway, but we’re sticking with our stars,” he said. “No one’s going to take those away.”

‘I cry every day’

Luc Dion and Julie Heon have been inseparable for the past year. Casual flirting on the terrace of the Musi-Café on July 6 turned into their first date. Then at 1:14 a.m. they were rocked as the oil train flew past.

As survivors, the couple say they have found strength in each other. Mr. Dion moved into Ms. Heon’s house on July 1.

“I feel bad for the people who try to imagine how it was there, it seems like they are being hard on themselves when trying to understand,” Ms. Heon says. “We were there, it was a stunning event that still wakes me up at night, but we’re moving past it, we’re dealing with it.”

The couple say they have little interest in joining any official anniversary ceremonies. But when the Musi-Café reopens, they would like to return with the other survivors and raise a pint to the victims.

“We’re constantly reliving that day,” says Ms. Heon, whose best friend died inside the bar after leaving the couple alone on the terrace. “I’m sad, I cry every day and I don’t need a ceremony to cry about it for three hours. I’m tired of crying.”

Mr. Dion expresses anger at the “politicking” he blames for much of the delays and frustrations in town.

“This used to be a small village, now it’s a very small village. It’s all politicking, nothing has opened yet and promises were betrayed. The hands aren’t following the words,” Mr. Dion says.

He worries when he hears the warning bells of level crossings, reminding him of the last sounds he heard before the MM&A oil train crashed. Ms. Heon has had similar trouble.

“I don’t hyperventilate or have a big panic,” she says, “but it really stirs the emotions.”

In the words of a four-year-old

In early August, four-year-old Édouard Pelletier will strap on his skates and head out on the ice. He’ll probably be the youngest person at Lac-Mégantic’s arena as he starts his first session at the hockey school named after his father, Mathieu Pelletier.

A math teacher at the local high school, Mr. Pelletier was a hockey prospect who bowed out of a full scholarship at an American university to stay with Alexia Dumas-Chaput. On the night of July 5, he headed out to the Musi-Café with two friends. One was visiting from Quebec City, the other from Switzerland.

Ms. Dumas-Chaput woke up early July 6 to frantic texts looking for her husband. His body was found at the Musi-Café. Following the disaster, Lac-Mégantic’s hockey school was renamed after its founder.

This winter Ms. Dumas-Chaput skated with her son and gave him hockey lessons for the first time. With Mr. Pelletier’s hockey sticks still in the garage, Édouard is continuing a passion shared with his father.

“Édouard doesn’t really understand that the school is named after his father, but it makes me really emotional,” Ms. Dumas-Chaput says. “I’m hesitating between being a typical mother in the stands or going down into the locker room and helping him dress up, which is what Mat would have done.”

As she and her son adjust to a new routine, she says life has never returned to normal. “Even in my nicest days, when I can appreciate my time with Édouard, there isn’t a day that I forget what happened. I get up alone, I go to bed alone, I remember what happened,” she says.

Mr. Pelletier’s son has lasting questions about what happened to his father, and about whether anyone will be punished as a result. MM&A and three of its employees, including the engineer that night, are now facing 47 charges each of criminal negligence causing death.

Édouard, Ms. Dumas-Chaput says, “has a four-year-old’s sense of justice and he thinks bad behaviour requires a consequence. Like everyone else, he needs to feel that someone assumes responsibility for their errors. He might not have the right sense of proportionality, he figures that they will get a time-out or be forced to draw something – he doesn’t understand prison time – but they need to take responsibility.”

Running a new railway

Before the accident, regulators in Canada treated oil as relatively low-risk and enforced few rules for classifying crude. Lac-Mégantic prompted municipalities across North America to demand better information about what moves through their communities by rail, and Ottawa now requires shippers or importers to have detailed emergency-response plans in place before they can send crude oil, ethanol and several other highly flammable liquids. The changes are among a raft of new rules introduced in Canada and the United States after the accident exposed glaring gaps in the regulation of the rail industry.

Still, Mayor Colette Roy-Laroche says she will continue to press for a rail bypass around Lac-Mégantic to ensure that hazardous goods are no longer ferried down a steep slope into town. So far, she’s received no assurances from either level of government and doesn’t expect to until they know how much it will cost.

The new rail company that has taken over the MM&A’s network has been under intense scrutiny at town meetings and in the local press.

At a public meeting with the Central Maine and Quebec Railway in late May, the CEO of the largest employer in town was the last at the microphone.

“I told them that they will need to run a safe operation, the population will be watching,” Mr. Brassard says. “In French I told him: Il faut que les bottines suivent les babines. You need to walk the talk. The room laughed, but it’s our responsibility as a customer to deal with a business partner that shares our values.”

He says he was satisfied with the veteran operators that look poised to run the new railroad.

However, the distinction between MM&A and CM&Q is belied by the fact that the new company, which just received permission to operate in Canada, is employing many managers who have come directly from the previous railroad. Four senior managers from MM&A are with the CM&Q on contract, while others have been hired into permanent management positions. The trustee for MM&A, Bob Keach, would not say which four were on contract.

A review of the new company’s phone directory lists MM&A’s former CEO, Bob Grindrod, as employed by CM&Q. MM&A’s former heads of human resources, marketing, transportation practices, budgeting, engineering, real estate and environmental affairs are all listed on the CM&Q directory.

‘Live life at its fullest’

Mr. Brier, at the high school, says he senses some concern among students about their future in the town. “We can feel that they are worried and asking themselves a lot of questions: Should I stay or should I go?” he says. Many have consulted the school’s guidance councillor.

Enrolment in extracurricular sports programs increased by at least 30 per cent last year, filling the gym from the end of the school day until 10 p.m. every weeknight. The accident left Lac-Mégantic’s children with few places to hang out.

The adults have their own questions – and some residents strike a mystical note. Whether for a laugh or for advice, Mr. Simard speaks daily with his friends who died. While the memorial candles crowd his credenza, he says the ghosts of his friends are there for assistance. “I never believed this before, but they are still here looking over us,” he says.

Mr. Lafontaine’s wife, Melanie, gave birth in the spring to a little girl named Élodie. Mr. Lafontaine muses that the child could be a way for those who died in the accident to return, and then quickly dismisses the notion. But, he adds, “You know, my brother Gaétan knew we wanted to have another child, so maybe he’s the one who sent her to us.”

Lac-Mégantic’s dead are still remembered, even before their names are inscribed on a planned memorial. Their presence is still felt around town, coddling friends on disquieting nights and providing a new appreciation for what hasn’t been lost.

“This isn’t just dark and drab,” Mr. Lafontaine says. “I’ve been given a chance, why would I waste it? I’m going to live life at its fullest. We’re all going to die, we all know that, so why not enjoy life while we can?”

Justin Giovannetti and Kim Mackrael are Globe reporters.