Hundreds and some days several thousands of vehicles drive through Paqtnkek Mi'kmaw Nation on the northern edge of Nova Scotia, just west of the heavily tourist-travelled gateway to Cape Breton Island.

Few actually see it, though.

Paqtnkek (pronounced buck-n-keg) is not technically invisible. But passersby have no direct way of accessing the reserve – they haven't for more than 50 years since the TransCanada highway was put in.

The road, which is lined by forest, was built to run through Paqtnkek territory but without access points into it; the highway not only severed the reserve in two, but its lack of interchanges meant that to access the undeveloped southern section of the reserve, a person would have to walk from the northern side across a busy, four-lane highway.

The 400 or so residents who live on the cramped north side, where the economy has never grown beyond sales of gas, cigarettes and convenience-store basics, must take a meandering route home from the highway via secondary access roads. The more brazen use a rutted, gravel track that has been ploughed through a section of forest, connecting the shoulder of the highway to a neighbourhood street.

The drive in to Paqtnkek is not one that anyone takes by chance. On other reserves, businesses serve the surrounding community and boost the local economy. To Paqtnkek's longstanding economic detriment, few outside it realize the community even exists.

That may soon change, as leaders in Paqtnkek are literally paving the road to revival. Band officials have spearheaded development of a new $15-million highway interchange that will provide direct access from the TransCanada to both sides of the reserve, including the promising southern parcel of land that has gone untouched for decades.

That property is slated to anchor a new $8-million commercial development on which Chief PJ Prosper is pinning loftier hopes than mere job creation for band members (a leasehold condition obligates tenants to hire from the reserve, and contractors on each phase must guarantee a minimum of 20 per cent of their employees are local Mi'kmaq).

The first phase of the 12-acre development, which will likely include an anchor tenant such as a major gas station or a fast-food chain restaurant, will also have room for small businesses that are expected to create jobs for members of the reserve and people who live in surrounding communities. As part of a unique collaboration, leaders from Paqtnkek have been working on an agreement with municipal officials at the County of Antigonish aimed at teaming up on efforts to grow both of their economies, which overlap due to geographic proximity.

Residents in both communities are hungry for job opportunities.

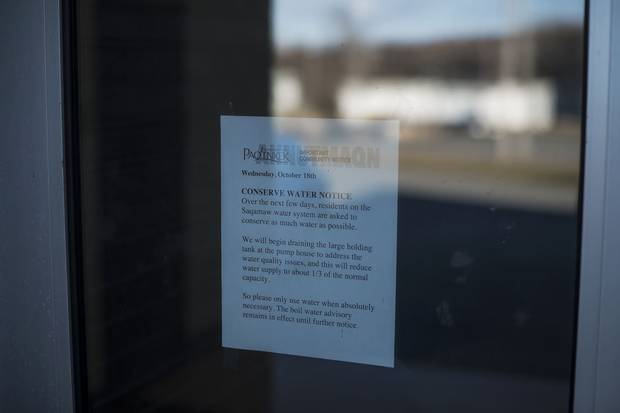

The reserve, Mr. Prosper said, is badly in need of a revitalized economy. Aging infrastructure is in need of upgrades, including the band's troubled water system which often requires residents to boil before drinking.

While the addition of new bricks and mortar are still a ways off, the prospect of change is already having an impact in the community.

"It has a way of allowing people to dream a bit of what is possible," said Rose Paul. As Paqtnkek's director of economic development, her job is to ensure the reserve's economic vitality; in addition to spearheading the highway interchange project, she has been leading community efforts to establish relationships with municipal and business leaders.

"Our young people are no longer looking at coming to the band office when they're 18 years old and getting a welfare check. They're bringing in their application to get a job and looking to set up businesses," she said.

"The paradigm shift is already happening."

That includes outside of Paqtnkek's borders, where momentum stoked by the band's highway effort has helped fuel the development of new relationships.

"We want to work more on collaboration than competing," said Owen McCarron, the warden of Antigonish County. "We see the opportunity for both reserve and non-reserve residents with the interchange project," he said. "As they court different businesses to set up in that location … we feel the benefit of creating more jobs and to Antigonish and surrounding areas is really huge."

Ms. Paul is working to ensure that. Last year she was named the country's top economic development officer by the national Council for the Advancement of Native Development. She also became the first-ever Mi'kmaq representative to sit on the local Chamber of Commerce in Antigonish.

"Not a lot of First Nations have strong relationships with the neighbouring municipality," she said. "Our goal is to do an economic development project together and remove these barriers that have been up for a long time," she said.

To make progress on that front, Ms. Paul applied for a grant from the Community Economic Development Initiative (CEDI), a national, federally funded initiative between the Federation of Canadian Municipalities (FCM) and Cando, a national Indigenous economic development organization.

Until recently, there was no real mechanism to connect municipal governments, who deal mainly with provincial officials, with First Nations, who deal mainly with the Crown, said Helen Patterson, the FCM's CEDI program manager. A pilot project that wrapped in 2016 after connecting six First Nations and municipal governments revealed the need for a guide to help build relationships between governing officials, who need to trade knowledge on governing structures, culture and decision-making processes and, of course, establish trust.

Ms. Patterson said CEDI now offers enrollees a toolkit to help guide the process, which aims for end goals such as joint planning on land use and economic development.

Antigonish County and Paqtnkek are one of 10 partners currently using the tool kit to explore new possibilities. Both councils have participated in a blanket exercise, a powerful role-playing model in which participants take on the roles of Indigenous people in Canada. Standing on blankets that represent the land, they are directed by a narrator that represents European colonizers.

The governments are also developing a relationship accord, which is a commitment to work together under common principles and goals.

"Two governments are going to be stronger together if they collaborate and plan together," Ms. Patterson said. "In some of these places, there is a real sense of possibility and planning together for growth. They're real pioneers in this First Nations-municipal relationship work."

Although there is still quite a bit of construction to be done, the future for both communities in Nova Scotia looks better than before, said the warden, Mr. McCarron.

"When we look at reconciliation, we can't necessarily change what has happened in the past," he said. "But we can make a concerted effort on doing a better job going forward."

IN PICTURES

Paqtnkek at a glance

A stop sign in Paqtnkek Mi’kmaw Nation. Access to the north side of the reserve (whose name is pronounced buck-n-keg) involves a meandering journey on secondary access roads, or for the more daring, a gravel track connecting the shoulder of the TransCanada highway to a neighbourhood street.

A water-conservation advisory is posted on the door to Paqtnkek’s community centre. Paqntkek’s troubled water system is a major part of the aging infrastructure that the band hopes could be improved by more economic development.

Travis Isadore, foreground, who has lived in the Paqtnkek reserve for 22 years, works on the highway interchange. The band is pinning high hopes on a commercial development that will have room for small businesses and a leasehold condition obligating businesses to hire from the reserve.

Outside the office of Rose Paul, Paqtnkek’s economic development director, a sign touts the future benefits of the highway interchange.

THE GLOBE IN ATLANTIC CANADA: MORE FROM JESSICA LEEDER