There are two warning signs at the entrance to Jackie Vautour's ramshackle New Brunswick homestead.

"It is because of you that the government is making us suffer as you can see," one reads. "Have a good look."

" Avis," the other continues. "Parc Canada sont defendu d'empieter." Which roughly translates as "Warning: Parks Canada are not to trespass."

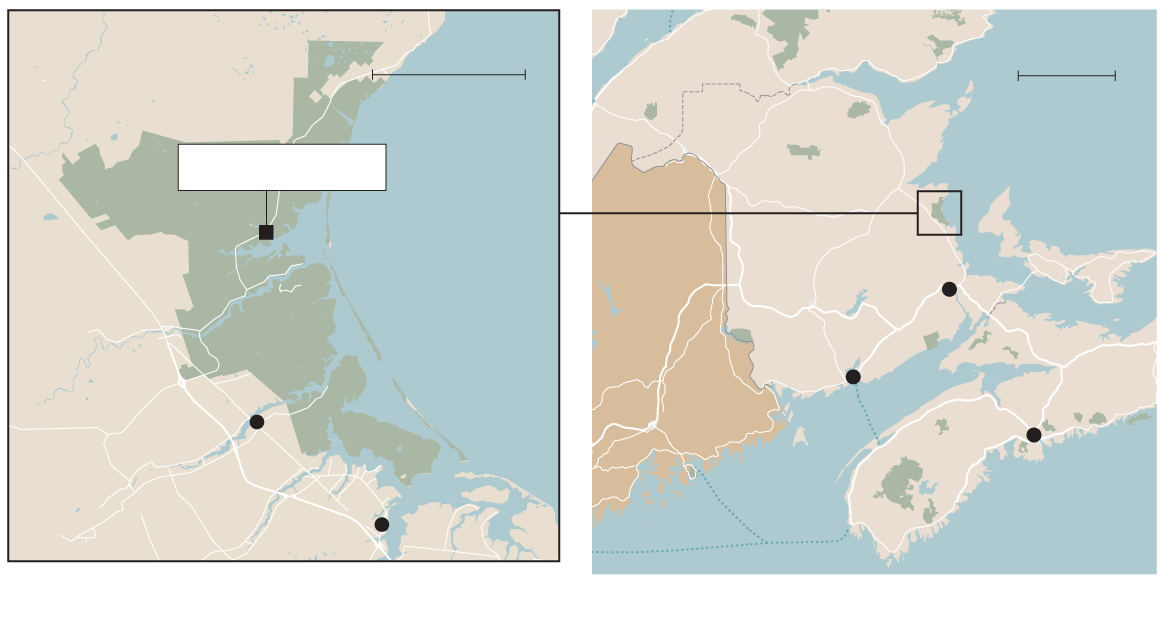

Mr. Vautour has squatted here, on the side of the highway in the middle of Kouchibouguac National Park, for more than 40 years in protest of the 1976 expropriation of his home, a government land grab that uprooted more than 1,000 people in seven neighbouring communities – about an hour's drive north of Moncton – as work for the national park began. It's where he raised nine children with his wife, Yvonne.

In more tense times, this two-room house overlooking Kouchibouguac Bay was central to a resistance movement waged by locals against provincial and federal authorities, a saga marred by violence from both sides.

Today, all other banished park residents have moved on. Tensions long ago subsided, but Mr. Vautour's resolve has not. Undeterred by decades of legal roadblocks, aborted or failed court challenges, waning public support and the fact that he's now 88, Mr. Vautour continues to fight the expropriation.

Warning signs in French and English urge Parks Canada employees ‘not to trespass’ on the Vautours’ shack in Kouchibouguac. It was once part of a community called Fontaine that was cleared away in the 1970s expropriation that built the park.

0

10

KM

Vautour house

Kouchibouguac

National Park

Saint-Louis-

de-Kent

Richibucto

0

100

KM

N.B.

PEI

Moncton

MAINE

Saint John

N.S.

Halifax

THE GLOBE AND MAIL, SOURCE: MAPZEN; OSM;

NATURAL EARTH; WHO’S ON FIRST

0

10

KM

Vautour house

Kouchibouguac

National Park

Saint-Louis-

de-Kent

Richibucto

0

100

KM

N.B.

PEI

Moncton

MAINE

Saint John

N.S.

Halifax

THE GLOBE AND MAIL, SOURCE: MAPZEN; OSM;

NATURAL EARTH; WHO’S ON FIRST

0

10

0

100

KM

KM

Vautour house

N.B.

PEI

Moncton

Kouchibouguac

National Park

MAINE

Saint John

N.S.

Saint-Louis-

de-Kent

Halifax

Richibucto

THE GLOBE AND MAIL, SOURCE: MAPZEN; OSM; NATURAL EARTH; WHO’S ON FIRST

The Rebel of Kouchibouguac (a nickname he hates because he believes it implies he is doing something wrong) is mounting his latest challenge with the Court of Queen's Bench of New Brunswick, asserting Métis heritage on behalf of himself and 126 other former park families.

Mr. Vautour and co-plaintiff Stephen Augustine, the hereditary chief for the region's Mi'kmaq people, are seeking aboriginal title to the park land. If successful, it could mean the end of Kouchibouguac National Park.

With this playing out at a time when Canada is attempting reconciliation with its First Nations people, Mr. Vautour's lawyer, Michael Swinwood, is hoping for a similar outcome to the 2014 Supreme Court decision that granted title of 1,700 square kilometres of land to Tsilhqot'in First Nation in British Columbia.

No statement of defence has been filed, but Mr. Swinwood expects the provincial and federal governments will argue that no Métis community ever existed at Kouchibouguac, a similar position taken against Mr. Vautour and his son Roy in a 20-year-old hunting– and fishing-rights case pending appeal at the Supreme Court of Canada.

It's another verse in Mr. Vautour's exhaustive attempt to have the land he lives on returned to him.

"The only way I keep moving is the almighty Lord and the strength in my belief," he says.

"No one can understand why I keep going. It's quite a thing. Just one day at a time."

The Vautour ‘castle’ is a home without running water, phone or hydro lines. Mr. Vautour has lived on this land since 1934, except for a two-year period after his eviction in 1976. He and his family returned to the land and rebuilt a home there.

A dilapidated scow, once used for fishing, sits in a field in Kouchibouguac National Park near the site where Mr. Vautour and his wife, Yvonne, were arrested for illegally fishing shellfish.

A man wades into the water along Kelly Beach in Kouchibouguac National Park. Mr. Vautour and a regional Mi’kmaq chief are mounting a legal challenge to seek Indigenous title to the park land.

'There is a folklore that he is the lone ranger'

A tear falls from Mr. Vautour's left eye onto the page in front of him.

"I'm not crying," he mutters, wiping the drop away with a tissue. "It's just that I have a bad eye. Had that ever since they pepper-sprayed my eye. I have a hard time crying. If I was a person like that, I'd have cried myself to death by now."

Rather than engage in an interview, Mr. Vautour reads from a statement that takes more than an hour to get through.

As he grumbles his way through events like the creation of the park, the expropriation and its effect on his family, and his role in the resistance, Mr. Vautour barely skips a beat.

Known for his bureaucratic prowess, Mr. Vautour keeps files that stretch back to the days when Louis J. Robichaud, the Acadian premier responsible for first creating the park in 1969, was in power. He recalls names of long-forgotten government ministers who came to visit him. He remembers dates and places.

But his rhythm is interrupted, and he goes off-script, when he reaches the details of violence that played out in the park's early years, specifically his family's removal from a motel at the hands of police in March, 1977.

The Vautours boarded in nearby Richibucto on the government's dime after police evicted them and bulldozed their home when they refused to abide by the expropriation.

When the province stopped footing the bill for their stay, the family refused to leave. To remove them, police used axes and tear gas before dragging Mr. Vautour and his sons to jail.

The melee was indicative of the tense and frequently violent climate around the park at the time between authorities and resisters. One former warden described the battles as "force against force."

Mr. Vautour shakes his head at the memory and sheds another tear. This one appears to surprise him.

"I don't know what's wrong with me," he says.

Mr. Vautour's toughness and resilience is the stuff of legend. Many view him as a folk hero.

He is a short, stoic man with a perpetual scowl. What's left of his cream-coloured hair is slicked back. He has sideburns and a handlebar mustache fit for a biker.

"There is a folklore that he is the lone ranger, standing up against big government," said Donald J. Savoie, the New Brunswick political scientist who grew up in nearby Bouctouche. "He became a symbol of resistance."

Jackie Vautour's popularity exploded when the public saw images and video of a government worker bulldozing his house in 1976. To that point, he was a community organizer, employed by a government agency, arguing for better deals against what were viewed as low-ball offers made to local landowners who lived in the park as the province, which was responsible for removing the inhabitants, tried to buy them out.

After his home was demolished, he became the face of a movement. In those days, Mr. Vautour was a mainstay in the press, drawing media attention from across the country. Reporters flocked to New Brunswick to report on the unrest in the park, which finally opened to the public in 1979.

With that exposure came praise and backlash, especially in Kent County, a largely Acadian area that also includes anglophone and First Nations communities. Mr. Vautour's actions earned him both followers and detractors. He became a polarizing figure for his outspokenness and grandstanding.

He says he's been targeted by death threats and campaigns to discredit his fight. There have also been innumerable visitors who've shown up on his doorstep asking to shake his hand.

Ronald Rudin, a history professor at Concordia University and author of the 2016 book Kouchibouguac: Removal, Resistance and Remembrance at a Canadian National Park, said for every person he interviewed who admired Mr. Vautour, there was another who resented him.

"It's totally mixed, it's divided," said Prof. Rudin, whose book details the creation of the park and the experiences of the expropriated families.

Attention to the land fight has faded over the years. Prof. Savoie believes people are tired of hearing about Mr. Vautour's plight.

Some locals roll their eyes at the mention of his name. Many believe he was fairly compensated due to his receiving a $228,000 payout (a far greater sum than any other expropriated family) and a deal for off-park land from then-premier Richard Hatfield in 1987.

"That's a fair chunk of change, but he didn't move," Prof. Savoie said. "That's why people think they've heard enough of him."

Mr. Vautour acknowledges receiving the money, which he says paid for his legal costs. He denies agreeing to vacate.

Mr. Vautour hopes his legal challenge will let him build the home he’s always promised his wife, Yvonne, left.

A kerosene lantern was the Vautours’ only source of light in the house until a small solar panel was installed.

Roughing it in the 'castle'

With the exception of a two-year period following his eviction, Mr. Vautour has lived on this property since 1934. It was once part of a community called Fontaine. All that remains is the Vautour "castle," which was rebuilt after he and his family returned to the land in 1978.

There is no running water in the house. Jackie and Yvonne Vautour use a portable toilet and bathe "the old-fashioned way."

"When people ask, I tell them, 'The same way your great-grandfather would've,'" Mr. Vautour says.

There is no cellphone service, nor do they have access to telephone or hydro lines.

A small solar panel powers the lights inside the house. Prior to its installation, a kerosene lantern was the only source of light. Any leftover juice from the panel is put into running a small television and DVD player given to them by their children.

"We've played a lot of solitaire," Mr. Vautour says.

The inside of the tiny home – a kitchen and small bedroom – is a shrine to Mr. Vautour, his fight and his family. Pinned up all around the house are old editorial cartoons, newspaper clippings and photos of the man they call the eternal rebel.

In the summer, the couple grows vegetables. Fried green tomatoes are a staple. They consume an array of boxed and canned foods like corn flakes and Kraft Dinner, while storing meat and produce in a cooler that costs about $7 worth of ice a day.

Every morning, Mr. Vautour gets up with the sun and goes for a walk down the road. He'll spend at least an hour working out in his home gym, housed in the garage. He'll bench press a rusted barbell, go through cable workouts on an old all-purpose machine and do some light cardio on a stepper. For breakfast, he eats tomatoes fresh from the garden, with a pair of eggs over easy and a bowl of cereal.

Yvonne Vautour, 85, keeps fit by skipping and jogging in the yard on sunny days.

Summer can be lovely, but winter is difficult to cope with as they grow older. A wood stove is the couple's only source of heat.

Their son Edmond Vautour worries during those cold months. As the child most involved with his father's legal fight, he is the contact for a majority of Jackie Vautour's affairs. He and Mr. Swinwood, the lawyer, are seeking approval from the government to build a home more appropriate for the winter. But because the Vautours reside in Kouchibouguac illegally, Parks Canada forbids it.

In a statement, the federal agency said it "will not and cannot authorize the installation of new services or dwellings for illegal occupants in the park."

In keeping with recommendations in the report of a 1981 special government inquiry, Parks Canada will not forcibly remove the Vautours, but the denial of services leaves the couple in a perpetual standoff with the government, neither side willing to budge.

Rather than leave, Mr. Vautour has always said he would die here.

‘The only way I keep moving is the almighty Lord and the strength in my belief,’ Mr. Vautour says. ‘No one can understand why I keep going. It’s quite a thing. Just one day at a time.’

'I never get tired of fighting'

The land-claim lawsuit may not change anything; Mr. Vautour could spend the rest of his days on the side of Highway 117, living illegally on land he used to own.

There are two parts of Jackie Vautour that people will remember, Prof. Savoie says. The first is the romantic idea portrayed in poems, songs, stage productions and documentaries of a man and his land, standing alone against the government.

His more tangible impact, however, is on public policy and how he changed the way land is expropriated, says Prof. Savoie. Governments no longer use the same heavy-handed approach employed at Kouchibouguac.

"What's the saying? 'Come the moment, come the man.' The moment came, and there arrived Jackie Vautour. Give him that. Someone had to do it," Prof. Savoie says. "For anybody, an individual, not a prime minister or a political organization, just a man, to have that kind of impact on the machinery of government, for that you have to give him some credit. That is no small achievement."

A verdict in his latest case could take years. But Mr. Vautour is long on patience.

He said he would like to see his fight settled in his favour before he dies. In the meantime, Mr. Vautour says he'll do what he's always done.

"I never get tired of fighting."

ATLANTIC CANADA: MORE FROM THE GLOBE AND MAIL