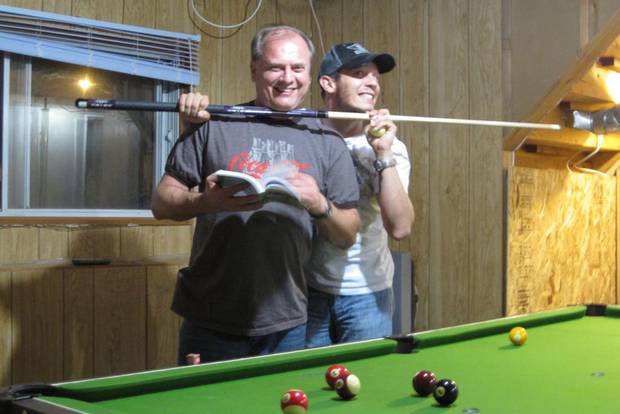

Corporal Shaun Collins, right, plays around with his father, Gary. Mr. Collins told a death inquiry his son had been a caring young man before his two tours of duty in Afghanistan with the Canadian Forces.

Courtesy Collins family

Gary Collins's voice trembled, his face reddened, and tears pooled in his eyes as he began to talk about his only son inside a silent Edmonton courtroom. He had sat at a small wooden desk for four days, poring over thick binders of exhibits and listening to 11 Canadian Forces members and mental-health specialists testify at an unprecedented Alberta death inquiry. Now, it was his turn to speak. He took a deep breath and pressed on.

His son, Shaun, was a teenager when he joined the reserves, not long before the terrorist attacks of Sept. 11, 2001, sparked the Afghanistan war. Deploying twice to the battlefield – first as a reservist and then with the regular force – Corporal Collins returned from his second tour haunted by nightmares and flashbacks.

"Shaun seen and did things over there that were against everything we taught our kids to respect," Mr. Collins told a group of mostly government lawyers gathered for the inquiry.

His son had been a caring young man. Mr. Collins recalled how he once bought a bus ticket to Fort McMurray for a panhandler trying to get to the oil-sands mecca. If only, he lamented, Edmonton military police had shown similar compassion on March 9, 2011, the night they arrested his son for allegedly driving drunk in a black SUV.

Within two and a half hours of that arrest, the 27-year-old corporal with the Princess Patricia's Canadian Light Infantry was found unconscious in a dark military cell, hanging from the metal-barred door. Cpl. Collins, who was being treated for post-traumatic stress disorder and clinical depression, died in a hospital two days later.

The inquiry, the first ever in Alberta to zero in on a military death, has exposed disturbing cracks in military police practices, equipment and facilities and in the Forces' mental-health-care system. The province's police watchdog – the Alberta Serious Incident Response Team – and the military completed separate investigations into Cpl. Collins's death, but their reports have not been publicly released. No criminal or military charges were laid in the case, a Canadian Forces spokesperson said in an e-mail.

Key breakdowns that came to light over four days of inquiry testimony included a lack of medical follow-up after Cpl. Collins asked for mental-health services after his second Afghanistan tour. Also, the military police team failed to adequately search the Forces' security information database and so were not aware of the corporal's previous suicide threats.

Meanwhile, video cameras installed to watch over soldiers in the Edmonton military police cells were not working and hadn't for years. And a defibrillator belonging to the military didn't work when officers and a friend of Cpl. Collins frantically tried to revive the soldier.

Cpl. Collins is one of at least 62 military members and veterans who have taken their lives after deploying on the Afghanistan operation, a continuing Globe and Mail investigation has found, an alarming number that had been hidden from Canadians until recently. Another 158 soldiers died in theatre, including six who killed themselves. About 40,000 soldiers served on the 13-year mission.

Provincial court Judge Jody Moher, who presided over the inquiry, cannot assign blame, but she can make recommendations to help prevent a similar death. Although the inquiry concluded last week, her report will likely take months to complete.

National Defence lawyers urged Judge Moher to limit the scope of her recommendations, arguing the province does not have jurisdiction over a federal entity such as the military. Mr. Collins, however, pleaded for the judge to weigh in: "Why allow an inquiry if you are not going to allow recommendations?" he asked.

It was a gruelling week for Mr. Collins, and more lie ahead for the Edmonton grandfather. On Monday, he returned to another courtroom for the first-degree murder trial in the death of his eldest daughter, Shannon. Her remains were found on an acreage just outside the city in 2008. Her boyfriend, Shawn Lee Wruck, wasn't charged until 2013. The trial is expected to last a month.

Signs of concern

Shaun Collins was a kind-hearted teenager when he joined the reserves shortly before the Sept. 11, 2001 terror attacks. The inquiry looking into his 2011 suicide, the first of its kind in Alberta, has exposed flaws in military jail safeguards and mental-health-care system.

Courtesy Collisn family

Torn apart by his sister's slaying, Cpl. Collins began seeing military social worker Shaun Ali in 2008. He told Mr. Ali that he believed he knew who killed her and was frustrated that police hadn't made an arrest. He also felt he was being harassed by members in his own unit because he had reported drug use by other soldiers.

Mr. Ali saw Cpl. Collins about five times over 11 months. The social worker said Cpl. Collins appeared to be doing well before he went to Afghanistan for his second tour in November, 2009, with the 1st Battalion of the Princess Patricia's Canadian Light Infantry.

During the tumultuous deployment, Cpl. Collins erupted in the field at a master corporal. He reportedly turned in his rifle to a fellow soldier and said: "Take this from me before I kill him." But some also heard, "Take this from me before I kill myself." Cpl. Collins was flown out of the battlefront to see mental-health workers at Kandahar airfield base. They determined that he was not a threat to himself, Major J.M. Watson testified.

The battle group spent a few days in Cyprus decompressing before returning to Canada in May, 2010. While there, soldiers filled out a form that asked whether they wanted to speak with a mental-health worker. Cpl. Collins answered yes, but the inquiry heard that no one from the military's medical system followed up until he called a help line in distress on Aug. 23, 2010.

Frustrated with the information he was getting, Cpl. Collins abruptly hung up the phone. Before he did, he said: "I'm done," and "I've had enough." Worried that he might be thinking about killing himself, a mental-health worker called for help and Edmonton police were dispatched to his home. Cpl. Collins told the officers it was a misunderstanding and assured them that he didn't want to take his life.

The incident led to a session with Mr. Ali. The social worker noticed significant changes in Cpl. Collins. He was showing signs of depression and anxiety. He wasn't sleeping well and was drinking more.

Cpl. Collins was referred for psychological and psychiatric assessments and anger-management counselling, but balked at addictions treatment. As his mental health continued to deteriorate, he threatened to take his own life twice in the fall of 2010.

The military prohibited him from handling weapons and transferred him to a woodworking shop with other ill and injured soldiers. The move was a positive change for Cpl. Collins. One of the soldiers he met was Everett Dalton, now a retired corporal.

"I tried to take care of him. Watch over him like a big brother would," Mr. Dalton said. "I recognized what he was going through."

Cpl. Collins wanted to get better. In early December, 2010, he turned to a psychologist outside of the military system because he worried seeking further help within would harm his career. Trauma specialist Keli Furman testified that "he was one of the most severe cases of PTSD" she had seen in her career. "There was clear evidence that he had been exposed to horrific events," she said.

Dr. Furman worked with him to control his temper and ground him to reality. A military psychiatrist monitored his medication. He was taking an anti-depressant, sleeping pills and an anti-psychotic to stabilize his mood.

Dr. Furman met with Cpl. Collins the day before he hanged himself. She said she saw no signs then that he was a suicide risk. He was excited about his future and about getting married. He recently got a cat and was enjoying his woodworking job. He hoped he could eventually rebuild his career in the Forces.

"He knew he had a long way to go, but he was highly motivated to recover," Dr. Furman said.

Lack of support

Cpl. Shaun Collins stands with his father, Gary, in this undated family photo.

Courtesy Collins family

The next day, on the morning of March 9, 2011, Cpl. Collins reported to the Joint Personnel Support Unit (JPSU) at the Edmonton base. The resource was created during the Afghanistan war to help seriously ill and wounded soldiers return to their military careers or train them for new civilian jobs and smooth their transition out of the Forces. He was nervous about being transferred to the JPSU, but also trying to remain optimistic.

But inadequate resources and a large number of war casualties have strained the JPSU. Over the years, internal reviews and the military ombudsman have pointed to chronic under-staffing and insufficient training at the support unit. The Forces is currently reviewing the JPSU and has pegged it for an overhaul.

On Cpl. Collins's first day in the JPSU, the platoon warrant officer and service co-ordinator were not there to meet with him. He left the support unit frustrated and went drinking at a bar on base for junior-rank soldiers. A bartender tried to stop him from driving off in his SUV, but the corporal didn't listen. As he drove away, the bartender called military police.

Cpl. Jason Pettem was a rookie military police officer in 2011. He pulled Cpl. Collins's SUV over on a busy street just outside the base shortly after 6 p.m. The soft-spoken officer told the inquiry that the soldier's eyes were bloodshot and that he admitted to drinking. Fellow military police officer, Sergeant Matthew Parkin, a corporal at the time, soon arrived at the scene.

…Cpl. Collins questioned their authority to stop him. When he was advised he would be detained, he got more angry and agitated, Sgt. Parkin testified.

The corporal was placed in handcuffs and taken to the military police guardhouse just before 7 p.m. He was searched and put in the solicitor-client room to call a lawyer. A dispatcher at the guardhouse was supposed to check the military security information database and the Canadian Police Information Centre (CPIC) for information about Cpl. Collins, but he misspelled the soldier's name, the inquiry was told.

As a result of the mistake, the officers were not aware of his suicidal history, which was recorded in the Forces database, but not in CPIC. No follow-up checks were done until after his hanging.

While Cpl. Collins was in the solicitor-client room, he was asked to perform a breathalyzer test, but he refused. Warrant Officer Dean Boyd, then a sergeant and the officer in charge that night, testified that the intoxicated soldier got aggressive and attempted to strike Cpl. Pettem with a phone.

Worried about the safety of the officers, WO Boyd decided to place Cpl. Collins in cell No. 1. He warned the soldier he would remain locked up for the night unless he started co-operating. Cpl. Collins refused two more breathalyzer demands. WO Boyd dimmed the lights in the cell and walked out. It was about 8 p.m. No one else was in custody that night.

A veteran of the Afghanistan war, WO Boyd planned to charge Cpl. Collins with refusing to provide a breath sample and release him to Cpl. Dalton, who was on his way to the guardhouse. Military police officers have the same powers of search, seizure and arrest as civilian police. They can lay both criminal charges and charges under the Forces' code of service discipline, which is part of the National Defence Act.

Cpl. Collins could be heard screaming from the darkened cell. At some point, the yelling stopped.

Around 8:30 p.m., WO Boyd and Cpl. Dalton walked into the cell block to free Cpl. Collins. They found him slumped, hanging from the cell door's bars by a noose fashioned from his combat shirt. The pair rushed to him. WO Boyd cut the noose off and started chest compressions. Cpl. Dalton breathed into his friend's mouth. A defibrillator was brought in from a military police vehicle, but it didn't work. The batteries were dead. A second defibrillator was retrieved. Firefighters and paramedics soon arrived and took over, but they couldn't save him.

Sgt. Parkin was choked with emotion as he recalled Cpl. Collins' hanging. Testifying by phone from Egypt, he said he and the other military police officers would not have left the soldier unsupervised in the cell had they known about his suicidal history.

Changes to the Edmonton military police guardhouse and practices were made in the wake of Cpl. Collins' suicide. In an e-mail, Captain Joanna Labonte noted that wire mesh was installed to cover hanging points and Plexiglas was used to shield the metal-barred doors. A functioning camera system was also installed, providing observation of the cells and surrounding areas. As well, all members in pretrial-service custody are now under constant physical observation and a defibrillator has been moved into the guardhouse.

Despite these changes, the guardhouse still doesn't meet current correctional standards, Capt. Labonte noted. Limits have been placed on how long members can be kept in the cells.

After Mr. Collins finished testifying at the inquiry, the judge adjourned for a break. Instead of burying his head back into the exhibit documents, he walked over to WO Boyd, who had been taking notes at the back of the courtroom.

The pair talked calmly for some time, each explaining their side, each wishing they could change what happened on March 9, 2011. The suicide of Cpl. Collins ripped a hole in many lives.

"I could tell you 100 stories about Shaun," Mr. Collins had told the inquiry. Afterward, he said: "He was so much more than that day."