In Kent Monkman's studio in west Toronto, there's a large painting based on Robert Harris's famous group portrait of the Fathers of Confederation. The delegates at the Charlottetown constitutional meetings of 1864 stand or sit in their accustomed places, but in the foreground, a nude figure lounges before the conference table, under the eyes of John A. Macdonald. It's Miss Chief Eagle Testickle, Mr. Monkman's alter ego.

"She's trying to get a seat at the table, or she could be a hired entertainer," said the prominent painter of Cree ancestry, whose works have been collected by major museums such as the National Gallery of Canada, the Glenbow Museum and the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts. Miss Chief is definitely sending up the self-conscious gravity of the delegates and imposing an indigenous presence on negotiations that scarcely acknowledged the aboriginal inhabitants of the territories under discussion.

The inclusion of Miss Chief in a founding image of Confederation is a characteristic move by the 51-year-old Mr. Monkman, whose work constantly messes with accepted visual codes. You approach one of his large-scale paintings imagining that you're looking at something familiar, but closer inspection reveals all kinds of transgressive narratives. He seems to be mocking painting modes of the past, but is also, paradoxically, enamoured of them.

"When we imagine history," writes Thomas King in his 2012 book The Inconvenient Indian, "we imagine a grand structure, a national chronicle, a closely organized and guarded record of agreed-upon events and interpretations." That kind of history becomes especially prevalent during big anniversary years such as Canada 150, when attempts are made to unite the population around a simple narrative of exploration, settlement and diversity.

Mr. Monkman's stories don't fit easily into that kind of streamlined national narrative, but he's determined to create space for them in our visual history. He has spent the past two years planning and executing work for his own Canada 150 project: a large touring exhibition called Shame and Prejudice: A Story of Resilience. The show, which opens later this month at the University of Toronto Art Museum, aims to set up a provocative friction between Canadian national myths, aboriginal experience and traditional European art practices.

"I wanted to deal with themes in my own life and my community, like colonization, the impact of Christianity and homophobia," he said. "I started looking at landscape painting and the art history of North America, as it was painted by Europeans, and at how they saw indigenous people. The subjectivity of that narrative needed to be challenged, and there were very few challenges to it in that idiom and that way of making images."

Some of Mr. Monkman's new paintings are direct, albeit stylized representations of headline events that have been repeated many times over in indigenous communities. The Death of the Virgin (After Caravaggio) shows the family of a young woman reacting dramatically to her death in hospital, apparently by suicide. The Scream illustrates the taking of indigenous children, for residential schools or forced adoption, in an open-air melee of priests, nuns and Mounties dragging children from their parents. In both works, the figures wear clothes of today, but have the stylized look of figures from a silent-movie still.

Other paintings in the exhibition see the history through a fantastical lens. The Bears looks like many Romantic landscapes, with golden sunlight spilling over craggy cliffs and a lake. But, in the foreground, bears rape and pursue bearded white men who could be the worthies gathered around the conference table at Charlottetown. Most are nude, some are wearing bondage harnesses and one is restrained by a neck tether held by Miss Chief, who this time is an avenging, whip-wielding figure in thigh-high red boots.

The Bears is allegorical, like another canvas showing the slaughter of beavers, some of whom appear to beg for mercy. As the beavers could be seen as stand-ins for native people, Mr. Monkman says, the bears represent indigenous spiritual traditions, within which the animals are often seen as powers that can be benevolent or destructive.

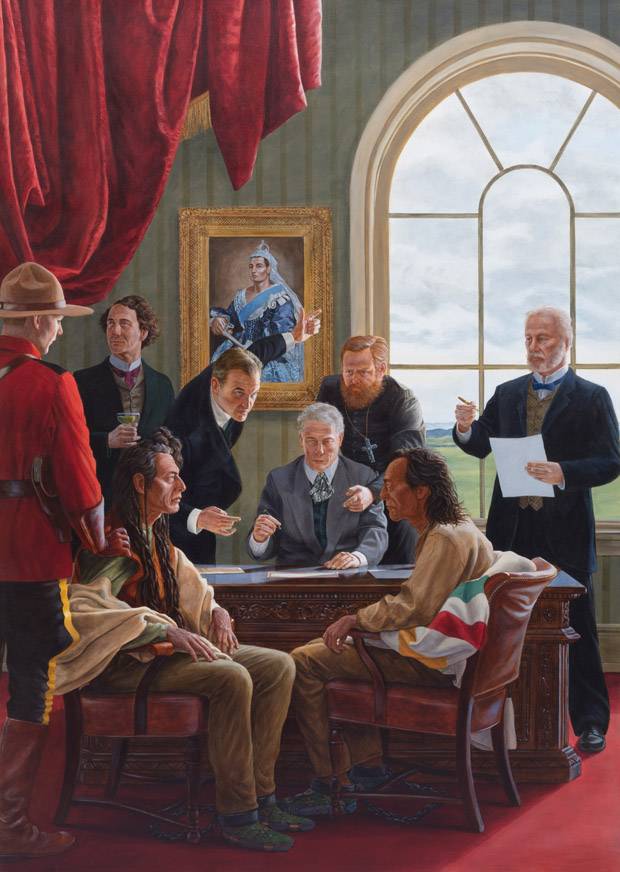

Subjugation of Truth shows Poundmaker and Big Bear sitting dejectedly before a table at which white men are signing away the chiefs' freedom. Sir John A. casts a dreamy look at a young Mountie, while a portrait on the wall shows Miss Chief in the guise of Queen Victoria.

"We try to sneak in things like that here and there," said Mr. Monkman, whose work is often salted with humour and parody. It's possible to imagine that his references to Romantic landscape painting and the histrionic poses of Caravaggio are purely ironic. But while Mr. Monkman is keen to disrupt and expand the colonial national narrative, he is quite sincere in his allegiance to the pictorial resources of the past.

"At first, I thought of Photoshopping contemporary images into reproductions of old paintings, but that's not what it was about at all," he said. "It was about absorbing the DNA of what painting can be, and looking back into art history, and saying, 'What makes a great painting? Can a painting still resonate and move people, and have emotional power that is specific?' That's when I started to look more closely at the Old Masters, because they were so good at expressing grief, longing and all these emotional things, through the shape of the human body or the face."

The paradox of Kent Monkman is that while he is a transgressive artist, he is also deeply conservative about the art of painting. When asked, "Is it your goal to do what Caravaggio did, as well as he did it, but now?" he replied: "That would be my goal. Absolutely. But no matter how hard I try, it will always end up being me." He criticized more contemporary-minded figurative painters such as the late Alex Colville, saying "there may be a mood or quiet feeling in his paintings, but they don't have the full range of human emotion."

Barbara Fischer, the curator who commissioned Shame and Prejudice for the U of T Art Museum, noted in a phone interview that Mr. Monkman is working within a contemporary tradition of artists "returning to certain media, forms or practices, but using them to achieve something different." Others might include Kehinde Wiley, who has painted Napoleonic equestrian portraits of African-American men; or Cindy Sherman, whose photographic self-portraits show her burlesquing famous paintings by numerous Old Masters, including Caravaggio.

"Monkman is availing himself of the language of a settler culture and in that language he's telling different stories about settler-indigenous relations," Ms. Fischer said. He recontextualizes Old Master conventions, she said, just as his paintings give new life to the museum artifacts that will be positioned throughout the exhibition. These include traditional cradle-boards, installed near The Scream; and a pair of Poundmaker's mocassins, near Subjugation of Truth.

Kent Monkman: ‘I wanted to work within the conventions to shock or surprise people.’

FRED LUM/THE GLOBE AND MAIL

Mr. Monkman's path to his current role as contemporary classical painter began in a small hospital in St. Marys, Ont., where his white mother had returned from northern Manitoba to give birth. He grew up mainly around his father's Cree family in Winnipeg. His great-grandmother, who lived in the same house till he was 10, spoke only Cree (he made a film and installation work about her in 2012, called Lot's Wife). His grandmother had gone to residential school and was one of only two of 12 siblings to survive into adulthood. He didn't hear her story from her directly, which is not unusual in families marked by the residential-schools trauma.

As a boy, however, he was less occupied with what could be told than what could be drawn. His school-teacher mother encouraged his creativity, which was further supported when he became one of the two kids from his school to be accepted into free Saturday art classes at the Winnipeg Art Gallery.

"I felt such a sense of belonging at the Winnipeg Art Gallery because I spent so much time there as a kid, not just in the art classes, but walking through the galleries," he said. From an early age, he knew that art would be his life.

He was also much impressed by the dioramas at the Manitoba Museum, with their painstaking 3-D recreations of how life was for aboriginal people before the white settlers arrived. But he felt a tremendous dissonance between those exhibits and what lay outside on Main Street, in Winnipeg's North End.

"I'd go to the museum with my school and see drunk Indian people tumbling out of bars, and then go inside and see pristine, precontact representations of the culture," he said. "I remember my classmates looking at me for some kind of explanation, but I had no way of even understanding how that happened." His family didn't live in the North End, where indigenous people make up one-quarter of the population, but in the mainly white neighbourhood of River Heights.

A high-school teacher suggested Mr. Monkman study illustration at Toronto's Sheridan College, because then he could be relatively sure of making a living from his drawing. It seemed to make sense: Mr. Monkman knew no one who lived by making art and hadn't seen any work by an indigenous artist till his teens. "Studying illustration was also a way of learning to draw and paint better," he said. "I didn't ever intend to be just an illustrator."

As figurative drawing and painting became associated in his mind with illustration, however, his idea of art took a more abstract turn.

"I thought the apex of painting was abstract expressionism, and that I had to make my individual mark as a painter, whether that was a drip, or a stripe or something else," he said. "I inherited the idea that the ultimate goal in painting was to find your own way of making a mark."

He did a series of somewhat abstract pieces called The Prayer Language, but judged the results "too personal and cryptic. People were left outside the work. That's when I decided I needed to be more specific, because I wanted to communicate."

He returned to figurative painting, which now seemed to him like a liberation from oppressive limits on what he could do and how he could do it. "I realized I could let go of the macho ego idea of making my own mark," he said. "I could disappear my hand into the work and that was a more confident way of making a painting. I didn't have to have an aggressive stylistic mark."

He became interested in 19th-Century painters such as Paul Kane and George Catlin, who depicted the expanding frontier of settlement and those who were about to be displaced into reserves. Both interpreted what they saw using European conventions of landscape art and European notions of blood-thirsty redskins and the Noble Savage. Mr. Monkman began to mimic their work, placing homoerotic situations and indigenous-positive imagery in landscapes made to look like they had been done on the Western plains in the 1880s.

"I wanted to work within the conventions to shock or surprise people," he said. "They feel like they're approaching a familiar form of landscape picture-making, but as they spend time with it, they're dislocated. They have to question everything they've received. That was a kind of disconnect I wanted the audience to have."

At the same time, he continued a personal polemic against the forms of abstraction that revolutionized painting in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Picasso in particular stood out, for his spirited demolition of figurative realism. Parodies of Picasso's cubistic depictions of women and bulls frequently appear in Mr. Monkman's work.

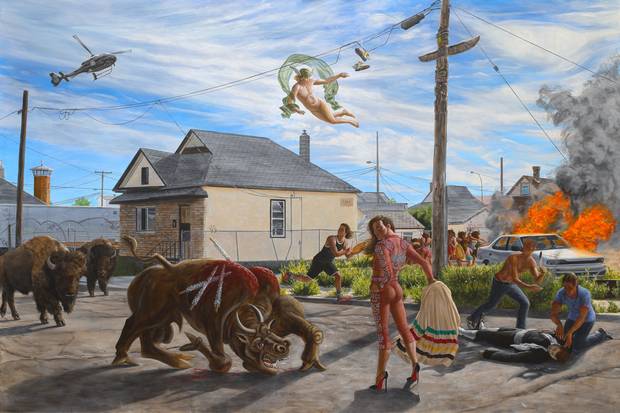

In Seeing Red, for instance, a Picasso bull paws the earth in front of Miss Chief, posing as a matador in Louboutin high heels, with a Hudson's Bay blanket instead of a red cape. A representation of Manet's naturalistic The Dead Matador lies nearby, attended by two aboriginal healers, while dancers in buffalo masks form a ring in the background.

Seeing Red. 2014. 84” x 126”, acrylic on canvas.

KENT MONKMAN

In Le petit déjeuner sur l'herbe (the title of which also alludes to Manet), several cubistic nudes lounge before a cheap Winnipeg hotel, in a parody of Picasso's Les Demoiselles d'Avignon, a famous group portrait of prostitutes in Barcelona. An expensive car is parked outside, implying that the owner is upstairs with another of the women. The abuse and violence implicit in the scene is underscored by a figure modelled on Picasso's air-raid mural, Guernica.

Le Petit dejuner sur l’herbe. 2014 84” x 126”, acrylic on canvas.

KENT MONKMAN

Picasso's modernist "butchering of the female nude," as Mr. Monkman calls it, is useful to him as a way of representing violence against indigenous women. He sees the whole modernist period in European art in parallel with the effects on indigenous communities wrought by other symptoms of modernity, including the railways and the Indian Act. Picasso also acts a foil for Mr. Monkman's own sensibility and sexuality.

"It's this tension between indigenous versus European, female versus male, a more classical approach to painting clashing with modernism," he said. "Picasso's bull was really the symbol of his sexuality and virility." All the more reason, he said, for it to be brought down by a gender-ambiguous matador, in Seeing Red.

Seeing Red and Le petit déjeuner sur l'herbe are both set in Winnipeg's North End, as is Cash for Souls, set outside a real-life pawn shop on Main Street, a three-minute drive from the Manitoba Museum. The painting is a parody of The Rape of the Sabine Women, with men in orange prison jumpsuits molesting women, as angels float overhead.

Cash for Souls. 2016. 48” x 72”, acrylic on canvas.

KENT MONKMAN

Angels are an ambiguous presence in many of Mr. Monkman's paintings, signifying grace perhaps, but also the destructive impact of Christianity on aboriginal communities. They typically look much as they do in sacred European frescoes, allowing him to allude even more freely to the Old Master paintings he reveres.

He copies them in another way, by running his studio like a classic atelier. He usually has at least one full-time painting assistant, to do underpainting and to help in translating small sketches and photo images onto large canvases.

"I don't need to paint every single layer," Mr. Monkman said. "Collaborating with other people is also more social and more dynamic. I have a team all working towards executing the artworks and they bring a lot to the process." There were half a dozen people in the studio the day I visited. A taste for collaboration has also led Mr. Monkman into theatre, performance-based installations and filmmaking.

"His work is very lateral," Barbara Fischer said. "He uses everything at his disposal, including museum collections."

For Shame and Prejudice, Mr. Monkman and his team visited museums across the country, looking for artifacts to display with his paintings. One room will feature a table splendidly laid at one end with fine china decorated with beaver imagery, symbol of early colonial prosperity for whites and native people alike. Toward the other end, the table becomes rough barn boards and "starvation plates," to show what happened to aboriginal communities when the beaver trade faltered, the bison disappeared and traditional lands were taken away.

That, too, is part of our history, though it may not figure in many celebrations of Canada 150. Party if you will, but Kent Monkman insists you remember the pain in our history too.

Shame and Prejudice runs from Jan. 26 to March 4 at the Art Centre of the University of Toronto Art Museum. The Four Continents, a show of Monkman works based on paintings by Tiepolo, continues at the Kitchener-Waterloo Art Gallery in Kitchener, Ont., through March 12.

Follow Robert Everett-Green on Twitter: @RobertEG_

CANADA 150: MORE FROM THE GLOBE AND MAIL