Day One

A lot of people like to drive when they travel to another part of Canada. But a seven-day, 4,638-kilometre bus tour from Toronto to Prince Edward Island and back with 50 Chinese tourists is another adventure entirely. So far, halfway through the first day, by aiming headfirst not just into the strange culture of bus tourism, but toward Charlottetown, PEI, one of the birthplaces of Canada, in this, our controversial sesquicentennial year – how much should we be celebrating? What about the land that was taken from others? Are we congratulating ourselves for systemic racism? – I have reached two conclusions about our complicated home and native land.

The first: It's a big country. That's why the bus has to pull over every two-and-a-half hours. People need a bathroom.

True, there is a bathroom on the bus. But Daniel Cheng, our tour guide, has banned the use of it "except in the case of an emergency," as he said in his opening announcement from the front of the bus at 8 this morning.

"What is an emergency?" Daniel continued. "Maybe if we have a three-hour long drive where we don't have a bathroom." Otherwise, the johnny-on-the-bus is to be avoided. "Because it's very smelly. No one likes smelling that."

Daniel, who's in his 50s, emigrated from Hong Kong to Toronto in the late 1980s. He's five-foot-eight and has the bearing of Napoleon. He runs a tight bus. "This will be a long trip, to the Maritimes by bus," he told us. He says everything in English, then in (self-admittedly bad) Mandarin, then in Cantonese. "So you have to have patience, and also enjoy." He wants us to keep the bus specklessly clean. "Tommy" – Tommy Lee, our driver, a six-foot-two francophone cowboy from Quebec City, late 50s, goatee, country music on his cordless ("great for driving") headphones – "will drive the bus all day. And he will be tired. So if you keep the bus tidy, he will like that." Most of all we shouldn't be late getting back on the bus. If we miss the bus, "Taipan Tours' policy is you have to pay for a taxi to the next hotel." Otherwise we ought to be content gazing out the window at the speeding landscape. "You can see the ocean. You can see the mountains. You can see the fields."

Our group with Taipan Tours travelled 4,638 kilometres from Toronto to Prince Edward Island and back.

Tour guide Daniel Cheng describes the sights in English, Cantonese and Mandarin to the travellers.

Some people think bus tours are purgatory on wheels. You see them in all countries and in every notable place, disgorging their curious and bewildered riders. I've always thought, what's that like? What kind of Canada do they see, though the lens of a different culture and a foreign language? What could they tell us about the place we live, the way we live?

There are 5,000 motor coaches touring Canada alone, averaging 50 passengers apiece nonstop from May until October. Each bus allegedly generates as much as $13,000 a day in economic activity. That's a $10-billion industry.

Canada's a piker in the booming bus-tour biz compared to the United States, Mexico, Europe, South America, China, the rest of Asia, and any other place with an emerging middle class. Baby boomers once shunned bus tours, but restricted mobility and fixed incomes are changing that.

Motor coach touring can even be luxurious. The website of Toronto-based Taipan Tours, the behemoth that's running ours – which advertises in English and Chinese, and to an international clientele as well – features a Gold and Diamonds Tour and a Wildlife Refuge Tour in South Africa; even an "Arctic Circle Tour: Meeting the Goddess of Aurora." In China there are tours devoted exclusively to sunsets, food, photography, and class reunions. The Chinese are the masters of the bus tour. If I'm taking one of these adventures, I'm going with them.

This tour – Toronto-Ottawa-Montreal-Fredericton-Halifax-Charlottetown-St. John-Quebec City-Toronto – is seven days and six nights for $658.05 a person. That's inexpensive. And the Maritime tour is one of the original see-as-much-as-you-can-for-as-little-money-as-possible tours beloved of the newly retired middle-class. We will spend hours blasting along the long green tubes of Canada's highways and stopping at famous (bathroom-equipped) "attractions." My fellow passengers will then spend tightly scheduled time taking pictures of themselves.

Which is my second conclusion: Whatever you think your country is supposed to represent, however holy its clichés have become, all newcomers – even tourists passing through quickly – make it their own. The bus will become their country, their temporary nation. Daniel keeps telling us we're "lucky" – when the traffic is good and we make time, when the sky opens with rain just as the last passenger clambers onto the bus. I hope he's right.

Toronto: I depart with the motor coach from Spadina Avenue in Chinatown.

Day One comprises a seven-hour hurtle to Ottawa; twenty minutes beside the Centennial Flame in front of the Parliament buildings; one hour at the Canadian Museum of Nature; another two-and-a-half-hour trek to Montreal, where we will have dinner at a Chinese chain before finally coming to a halt in the old city. Tomorrow is Fredericton. A coach tour rarely stops for breath.

"You may wonder," Daniel says in Cantonese but not in English as we pull up in front of the Parliament buildings, "why so few people live in the national capital. But Canada only has 33 million people." There are nearly that many people living in Shanghai alone.

In front of the national flame, Caroline Wu snaps pictures of her husband Ken Chau – born and raised in Hong Kong, they live in Vancouver – with his Hong Kong pals: Stephen Ho, Kai Ho, and Lan Wing Hong. They're all in their 60s, and have known each other since Grade 7. Why did they come on a lightning bus tour? "Oh," Ken says, as if it were obvious. "To share our friendship."

"So not just to see this national grandeur?" I ask, waving at the Peace Tower, temporarily obscured by a bandstand.

"No, not just for this," Caroline replies, smiling at me as if I were slightly soft in the head.

Next stop: the Canadian Museum of Nature. "Other tours," Daniel claims, "they take you to other places, like the War Museum. It's not interesting. This Nature Museum is very interesting."

In Montreal, our next stop, we dine at Fu Lam, an all-you-can eat Chinese buffet. I had forgotten how delicious they are. On our way through the city, we pass Au Pied du Cochon, the famous restaurant where Martin Picard pioneered Canadian nose-to-tail cuisine. "Very famous for pork chops," Daniel tells us.

Outside Quebec City: One of the passengers takes a photo at a rest stop.

Day Two

To Fredericton today, hence an early start: Breakfast at 6 a.m. (McDonald's), baggage loading with Tommy Lee at 6:45, departure at 7. Within 20 minutes, the entire bus has conked out. It's kind of sweet. A wide range of neck pillows are in use, including the latest models, a head brace that looks like a Dairy Queen soft-serve ice cream, and another inflatable crate you thread your arms through and sleep on face-first, leaning forward, as if you were vomiting into a toilet bowl. They all seem to work.

The ride is surprisingly smooth – a $700,000, 55-seat MCI six-wheeler with a 700-litre gas tank. The windscreen is two-and-a-half metres high. Tommy averages 116 kilometres an hour and never uses cruise control. "Pedal," he says, pointing to the toe of his cowboy boot. Tommy Lee drove a long-haul truck for 35 years before he became a bus driver for Autobus Laval, out of Quebec City. He met his current girlfriend, Jane, on his last Taipan Tour last fall. She's Chinese and lives in Hangzhou, a city of 10 million. They're talking about moving to Toronto together. "Which day of the tour did you meet her?" I ask. It's a lot to pack into seven days.

"The first!"

Tommy and I are the only Caucasians on the bus. It's an unfamiliar feeling for me, to be what the Chinese call laowai, an old outsider. There are two women, from Lahore and Kashmir, respectively – the woman from Lahore has been living in Toronto for seven years, while the other moves back and forth from India – who, along with a few others, have paid extra to keep their seats at the front, while everyone else rotates day to day. Of the remaining paying customers, a third are from mainland China, a third from Hong Kong and Taiwan, the rest Chinese-Canadians travelling with friends or family.

Two couples have already complained that they want more time in museums. Kewei Sun and his wife Suyan Wu, youthful-looking 62-year-old retirees, are on a month-long visit from Wuhan, in the middle of China – a city with 10 million inhabitants and a 3,500-year history. It's hard to imagine what they must think of dinky New Brunswick. But they loved Niagara Falls and Toronto's Casa Loma ("really beautiful") before they climbed onto the Maritime bus. "I like the green coverage," Ms. Wu says. She means the trees and fields that line the highway, the boreal tunnel Canadians lament as boring. "The air is so clear," she literally sighs. "The sky is so blue." Our everyday gifts. The only time the air in Wuhan is this clear is after two solid days of rain.

At 9:08, Daniel taps the mic and wakes everyone to pee at a rest stop somewhere near Belleville, Ont. Chienming Wu, a retired and widowed bio-electric engineer from Taiwan, is taking his first vacation with his new girlfriend, Joanne Chang, formerly of Taiwan but now a language teacher in Toronto. They were introduced online by a matchmaker last January, met in person in Taiwan in March, and are travelling together for the first time. They're still getting to know one another. He's 60 and has a ponytail beneath a straw hat; she's 48 and shy. At the moment he's lying in the grass of the rest stop, shooting close-ups of dandelions.

This morning's on-bus video entertainment is Chinese Zodiac, a chop-socky epic starring Jackie Chan. (Yesterday's was Mr. Bean, a big hit.) By 11:45 we're at lunch again, again at McDonald's. There is a particular look that overcomes the faces of local customers in a McDonald's when 50 foreign tourists pile in – a shocked despair at the thought of how long the wait will now be. Daniel gamely helps the non-English speakers, stationing himself beside the cash and pointing to menu pictures behind the counter. "Beef?" he shouts in his imperfect Mandarin to Mr. Wu, who shakes his head and points to the chicken. Chicken it is. "Potato?" Daniel asks? He means fries. Yes. Soda? No, coffee. That can happen 30 times a lunch. The servers only ever look at Daniel. It's a challenge to order, eat and urinate within an hour, especially given the lineup trickling into the women's. But we do it.

Grand Falls, N.B.: Some travellers stop to look at a statue of Malabeam, a woman remembered in Maliseet legend for sacrificing herself to defeat a party of Mohawk invaders.

Grand Falls, N.B.: The travellers take photos at the waterfalls that give the town its name.

The first of our three afternoon attractions, ladies and gentlemen, is Grand Falls, N.B., site of the famous cascade where noble Malabeam, a daughter of the Malecite tribe, once led a raiding party of enemy Mohawks to their (and possibly her own) death over the falls to protect her village. Alas, today the dam's closed and the cascade's a trickle. The second "program," as Daniel calls it, is 45 minutes at the world's longest covered bridge (390.75 metres), built across the Saint John River in 1901 at Hartland, N.B., former hometown of Richard "Disco Dick" Hatfield, the long-serving, pot-carrying, party-loving gay premier and civil-rights warrior of New Brunswick, who gets no mention from our tour guide. The third is the Covered Bridge potato chip factory, which we wait to experience while two other Asian tour groups leave. Collectively, the bus buys at least 100 large bags of chips. The best-seller is lobster flavoured. Grandma's Hot Apple Pie variety, no thank you.

By 6:20 we're on the road again, headed for Fredericton. By 8:00, we're eating pho at Saigon Noodle House, one of the few Fredericton restaurants that can handle 50 customers at such a late hour. (This is the country we live in.) By 9:00, we're massed in the lobby of the Best Western on the edge of town, as Daniel checks us in.

By 9:30, we're in our rooms. No one ever goes out at night, not even to the hotel bar. Karen Chau, from Hong Kong, is travelling with her 79-year-old father, Tung Ki, her sister-in-law Vivien and her niece Athena. The women share two double beds in one room, while Tung Ki and his long-time travelling companion, who doesn't want his name used, gamble and play cards (and sleep) in the other. The gang of pals from Hong Kong have two rooms as well: Caroline Wu and the taxi driver's wife sleep in one, while the four buddies kip in the other, two to a double bed. Every night before they do, Kai Ho slips down the hall to get a bucket of ice. "It's good for the humidity," he says. "In North America the air is so dry."

I sometimes go down to the bar anyway. Tonight I meet a guy named Ken St. Jacques, who belongs to the Maliseet First Nation, the Indigenous people of the Saint John River valley. He retrains people in his band and finds them jobs in fish plants in Newfoundland – jobs that are now being snatched back by returning Newfoundlanders who've lost their jobs in Fort McMurray because of the oil slump. Life out here looks simpler than it is.

Halifax: Theodore Too, a tour boat based on the TV show Theodore Tugboat, takes tourists to see the sights.

Day Three

On the morning ride to Halifax, while everyone else sleeps, Alice Xu tells me there have been rumblings of complaint among the passengers. Several mainlanders are unhappy with Daniel's sketchy Mandarin, to say nothing of his cursory historical details. They're also upset about having to tip him ahead of time.

"Of course," Alice adds, "I want more history, for my son." Alice, an accountant, and her husband Dave Chen, a shopping mall consultant, live in Los Angeles, having emigrated from Shanghai as students (business and computer engineering) in the 1980s. They're travelling with their 12-year-old son, Jason, who is aiming for Harvard. "For my son, I said, why the potato chip factory? But this isn't a personal project. This is the group. Some people want the museum. Some want the food. The company wants to please the widest possible range of people."

Why do people travel this way? "First of all," Mr. Wu says, "because of the language barrier. And also, because everything is arranged – food, hotels, everything. And it permits people to go to as many places as possible." It's also cheaper. Dave Chen usually budgets $3,500 to $4,500 per person for a week of non-bus vacation, such as when they fly to visit Alice's mother in New Jersey twice a year. This bus trip is half that. "Driving," he says, "you have to follow the map, and that produces arguments. This way, that way. I'm not good at directions. They call me the U-turn expert." But however you go, "you always have a story afterwards."

For Chinese retirees in their 50s and 60s who have experienced the transformation of their country from a communist dictatorship into a money-crazed market economy, even a frantic bus trip to Moncton feels like paradise. As a student in Shanghai in 1982, Alice Xu earned $36 a month. "And that was not bad." Today, at that same job, "right now, they earn $1,000 a month, U.S., in Shanghai." But life there is fiercely competitive, especially for young people in large cities. Alice looks up at her son Jason in the seat ahead, sleeping next to his father. "Until he's 18, you have to give him good opportunities. Time is the most important thing for these kids."

Time is a commodity a bus trip has in abundance.

Suddenly Daniel is on the PA system again. "So, go to the washroom first. Because maybe a third bus is coming." We are in Amherst, N.S. If you walk off the bus and around the boardwalk to the other side of the gift shop you can see the banks of the Bay of Fundy glistening like red eyebrows over the silver slit of the water. Dave is sniffing as he gets off the bus. "I can smell the sea." He sounds excited.

Peggy’s Cove, N.S.: The travellers mill around the Peggys Point lighthouse in Nova Scotia’s St. Margarets Bay.

Having raced through Halifax's Maritime Museum of the Atlantic in an hour – the Titanic got some attention, but the Halifax explosion of 1917 might as well never have happened – we are hauled to Peggy's Cove. The famous fishing village is stunningly beautiful, or would be if the cracked grey granite reaching down to the sea weren't swarming with tourists trying to see how beautiful Peggy's Cove is. And this is only May.

But if you turn around, away from the sea and crowds, and focus on the red and yellow and blue shacks on the rocks, you can pretend the crowd isn't here. That is where you will see Mary Zhang. (She uses her "English" name, for fear the Chinese government will restrict her ability to travel. "That would be the end of my spiritual life," she says.) She's a retired journalist from Ningxia Province in northern China.

This is her first trip to Canada, though she is a veteran of some 20 international coach tours. She bought a new dress for the trip, dyed her hair a dark rose. She loves to pose for the camera of her husband, a medical specialist. Dramatic poses: arms extended, legs fore and back, long colourful scarves in the air, sitting, pointing, and always smiling. The unusual thing is that her poses never seem insincere.

She too loves the air and water and green of Canada. But it's the traffic that impresses her most. As China's cities expand, so have its daily commutes. "I see humanity through traffic," she says. "Cars here will stop for people, let pedestrians go first. In China, cars go first." (Maybe she should visit Toronto.) "China has a big population. Maybe people don't have the same regard for each other there. I feel people have less stress here in Canada. When we were in Montreal, I saw people sitting outside, drinking beer, eating dessert and laughing. It seems like they have a happy life. In China, people don't really sit in the sun a lot. And they don't spend money." She thinks for a moment, squinting. "Now that the standard of living in China is improving, people want to live in the moment, and see the world. For Canadians, it's a vacation. We rarely say we're having a vacation. We say we're going travelling."

But she recognizes the pitfalls of rushing through a country, never stopping to examine anything closely. "It's kind of a joke in China: sleep on the bus, pee off the bus, take pictures when you get to the destination. And you know nothing when you get home." There's an ancient expression for this, sometimes attributed to Li Bai, the 8th-century A.D. poet of the Tang Dynasty, the last time China dominated the known world: Ride a horse to look at the flowers. It never works, hence Mary's pictures. "They're the documents of my life. When I'm older, they'll be a way to remember what happened."

Peggy’s Cove, N.S.: While the granite shore and lighthouse were swarming with tourists, it was possible for us to pretend the crowd wasn’t there by looking inward.

As for the endlessly touted lobster dinner served by Murphy's Restaurant on the tour boat tootling around Halifax Harbour, let me say this, given the Chinese reverence for lobster: The tour was excellent, in both English and Chinese. The lobster was the worst I've ever eaten. It was the smallest legal lobster I've ever seen, and so overcooked and vulcanized it could have been used as a Yanomami slingshot. Murphy's serves 12 such lobster roll-outs a week off this one boat during peak season, 80 per cent of them to Chinese bus tours.

On the other hand, I have never witnessed so many skilled lobster eaters in my life. I know my way around a homarusian chest cavity. My busmates put me to shame.

Halifax: The lobster was the worst I’ve ever eaten.

Hopewell Rocks, N.B.: We lucked out in getting to Chignecto Bay, at the head of the Bay of Fundy, when the famed clay-and-sandstone rock formations were exposed by low tide.

Day Four

Our first stop today is a huge success with my comrades because – thanks to low tide – we get to walk on the beach at Hopewell Rocks (a.k.a. the Flowerpots), the teetering red-clay-and-sandstone plinths formed by the 20-foot tides on the New Brunswick side of Chignecto Bay at the head of the Bay of Fundy. It's as if the Bay has momentarily relented and let us see its secret brain. "So we are very lucky," Daniel says. He sets us free for more than an hour.

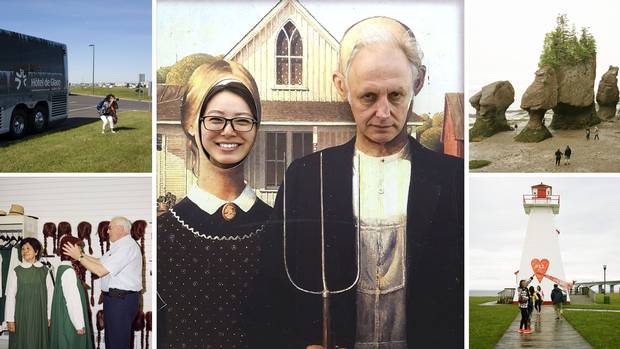

From there we make our way across the cubist angles of the Confederation Bridge, across PEI's red and green quilt of fields to Green Gables, the Cavendish farm house that inspired Lucy Maud Montgomery to write Anne of Green Gables. Anne is a cult figure in Japan. She is much less well-known to most people on our bus – Chienming Wu and a few other keeners excepted. Mr. Sun says, "the only Canadian the Chinese know is Norman Bethune." I didn't finish the book myself, despite its charms. But everyone happily tours the site: It's filled with old things and gardens. My bus companions like to look at old things and gardens.

But tensions emerge as the tour wears on. Karen Chau, the fashionably dressed woman from Hong Kong, has asked Daniel if she can sit at the front of the bus: The man in front of her, from mainland China, keeps peeling oranges, and Karen can't stand that smell. Today on the bus she is actually wearing a mask. Like many Hong Kong residents and emigres on the bus, Karen is wary of mainland Chinese. "I don't like their attitude," she says. "They're rude." She was recently standing in a queue in China when someone cut in front of her. "I said, the end of the line is back there. And their answer? 'It's my country, I don't have to line up.'"

Cavendish, PEI: One of the travellers dons the signature Anne of Green Gables hat and red pigtails at Green Gables Heritage Place.

Cavendish, PEI: Ian Brown, left, takes notes as the travellers enjoy the red sandy vistas of Cavendish Beach.

Day Five

Prince Charles was once asked how he liked travelling around on the world on the family yacht, the Royal Britannia. "I'd rather go by bus," he replied. "There is nothing nicer in the world than a bus." He was seven years old at the time.

Riding the bus can feel childish. Daniel never goes into complicated historical detail about the sites we visit. He didn't delve deeply into the Acadians or the Indigenous history of the Maritimes (though we passed through band land), but he did say, as the bus rolled down the hill into Halifax, "more high-rise buildings. Better than Fredericton." It's like having Pee-Wee Herman as a tour guide. This morning we proceed to Province House in Charlottetown, where Confederation itself was conceived in 1864, presumably one of the highlights of the tour – 150 big ones, baby! – but Province House is under extensive renovation, and we slip by it with barely a mention, as if it were an embarrassing old farting uncle. It's also Sunday morning, so everything's closed, except the Cows Ice Cream store. If Cows is ever closed in PEI, check your pulse.

But it isn't until we pull off the highway at Shediac to pee again and take pictures again, this time in front of Shediac's giant 55-tonne black-and-orange sculpture of a lobster (commemorating "the home of lobster") that the pent-up irritation with being treated like children finally surfaces.

"I think I will not go on this sort of bus trip again," the woman – a Torontonian, born in Lahore – who has been sitting at the front of the bus tells me, as she waits for the bathroom. (She doesn't want me to use her name.) "Too much regimentation. Maybe too much condescension. He's always saying 'do this, do that.' Maybe a little more English would help." (She speaks five languages herself.) "This is Canada, after all; it started out as English and French. Maybe we could have had the history of Acadia, how the French came, and then the English came and expelled the French? Or something about Confederation as we went over the Confederation Bridge? If I didn't know about the history of this country, what would I have gained from this trip? Taking pictures, getting off the bus, getting on again. But how would I have been enlightened? He's treating us like children. Maybe these people want to be treated like children."

This is scathing and casually racist, and upsets me: The woman is well-read, well-spoken, intelligent, Canadian. But she feels excluded and insulted, and has turned against the tour, possibly the bus, too.

It's only later, waiting for my companions to pass through the desultory souvenir shop at Moncton's Magnetic Hill – the most craven tourist attraction in the country, bar none, where the so-called "optical illusion" doesn't really work, because to see it, you have to be looking ahead through your windshield, and that's hard to do from the back of a bus – that I figure out why the trite, repetitive attractions are as dispiriting to me as the woman's trite, repetitive narrowness.

If you celebrate only the established clichés of a country, such as the big birthdays and the status quo, which is what tourism and big-chested patriotism do at their most commercial and venal and unthinking, you automatically reduce the country and yourself to a simplified, childish state. This is the decadent world of clichés that pretend the country never changes. They are usually the clichés of the ruling classes, but they can be the clichés of the oppressed as well. If you try on the other hand to understand the country on a more authentic and truthful level – not just as a pretty illusion, but as a complicated morass of struggle and power and failure and sadness and also of beauty and yearning and hope and even humour, it's more interesting, and certainly more realistic.

By the time we get to our hotel for the night, the grandly named Château St. John – a square brick box with two red metal dunce cap roofs to evoke the concept of "château" – a heavy mist is oozing over St. John. "It's foggy," says Daniel. "So it's just like London here." I can't say it was the first place I thought of, but I admire his optimism.

Quebec City: From the Capital Observatory, the city’s highest point, we could get a 360-degree view.

Quebec City: Old Quebec City was a big hit with the tourists.

Day Six

My travelling companions love Quebec. They love to stand on the public observation deck overlooking the old walled city: From there the St. Lawrence looks like a giant vein. They especially like to measure their height against a wall chart depicting the average annual snowfall in the city (304 centimeters!). None of us come much more than halfway up the scale. We all find this hilarious and thrilling.

After a visit to the Quebec City aquarium and a brief tour of the old city with Daniel, we gather outside a red-roofed restaurant in front of the Château Frontenac for our last "European" dinner. The restaurant is Old Quebec to the point of nausea: There's a man in a red cap inside playing Que Sera, Sera on an accordion. A smarter fellow is playing Chinese love songs on a saxophone outside: A majority of the 12 buses the restaurant will serve tonight will be Chinese tourists.

I find myself sitting on a wall next to Joanne Chang. I ask her how her new relationship with Prof. Wu is faring. Quite well, apparently. She likes him. "His personality is very good. He's tolerant. I'm a Christian, so from the beginning I prayed to God: when I feel something, I just ask God if it's right." So far the answer seems to be yes. Because the tour handles everything, they've had time to get to know each other. "At his age, you know yourself very well. So you know what kind of person you can connect with. So you don't have to take a lot of time to connect."

A few minutes later I sidle over to the professor himself. Can it work? "Huh," he says. He thinks. "Maybe," he says. He nods. "Yes, maybe."

Thousand Islands, Ont.: We take a final cruise on their journey back from Quebec City to Toronto.

Day Seven

Last day. To make it back to Toronto from Quebec City with time for a final cruise around the Thousand Islands near Gananoque, Ont., we have lunch, our fourth and last all-you-can-eat Chinese buffet, at 10:45 in the morning. I have eaten so much – Chinese food and McDonald's, plus two paltry lobsters – in seven days, I imagine my alimentary canal now resembles Lake Erie.

The boat turns out to be packed with bus tours – at least three Chinese buses, but also Spaniards and Mexicans. It's a gorgeous sunny day, as brisk as a broom, and breezy. The clouds on the horizon are huge meringues, if meringues can race in the Indy 500. You can spend a lot of time looking at the sky in this country.

Eduardo Valdez sits next to me on the open upper deck of the boat as we cruise past million-dollar island cottages. Eduardo is in his forties, an extrovert. We get to talking, despite my lack of Spanish. "I have a little English," he said. "I can say food and beer. It's enough." He's from Monterrey, Mexico, near the Texas border, and is on a four-day jaunt to Ottawa and Montreal. Eduardo originally planned to take a bus tour of San Francisco, but then Donald Trump happened. He finds Canada "beautiful. The water. The mountains." That old story.

My busmate Alice Xu is sitting on a bench across from us. Quebec City was her favourite part of the trip, but, she now admits, "it could be this."

Then she looks at Eduardo. "Espanol?" she asks.

"Claro."

"From where?

"Mexico." He nods at her. "You? Montreal?"

She shakes her head, but smiles. I wonder if she's flattered. "Los Angeles."

"Ah," Eduardo says. He nods and opens his hands, as if this were the most natural thing in the world, to find himself, a Mexican, on a boat in the Thousand Islands of Canada, standing next to someone from China, who lives in L.A. Someone from so far away, and different, and yet now so close, and similar. Some people want to understand the country. Some want to experience it. Both begin by witnessing it. That is the way of the bus.

Thousand Islands, Ont.: Tour guide Daniel Cheng and driver Tommy Lee, at the journey’s end.

Ian Brown is a feature writer at The Globe and Mail.

Xiao Xu, a reporter and translator in the Vancouver bureau, contributed files.

CANADIAN JOURNEYS: MORE FROM THE GLOBE AND MAIL