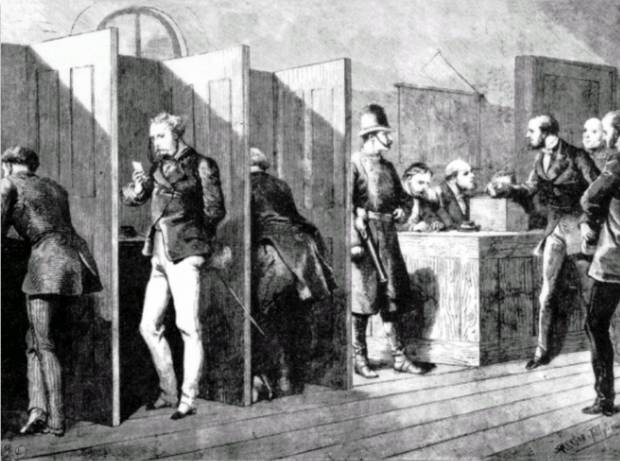

Globe backs the secret ballot

The Canadian Illustrated News

Oct. 2, 1867 – At the time of Canada's Confederation, most voting was done in public, where friends, relatives or anyone else could hear how an elector declared his choice at the poll. A few jurisdictions, including New Brunswick, let voters mark ballots privately, but that was still rare. In an editorial, The Globe threw its support behind the secret ballot, saying that "the arguments in its favour are so plain, that few will make any determined fight against the change." Elections in New Brunswick were more "quiet and orderly" under the secret system, the paper said, and they experienced less violence than polling elsewhere. The secret ballot allowed the "real, honest opinions of the electors" to be expressed without undue pressure from landlords, employers, clergy or creditors, The Globe argued. In 1874, Ottawa adopted the secret ballot for federal elections, and eventually it became common practice in all provinces. – Richard Blackwell

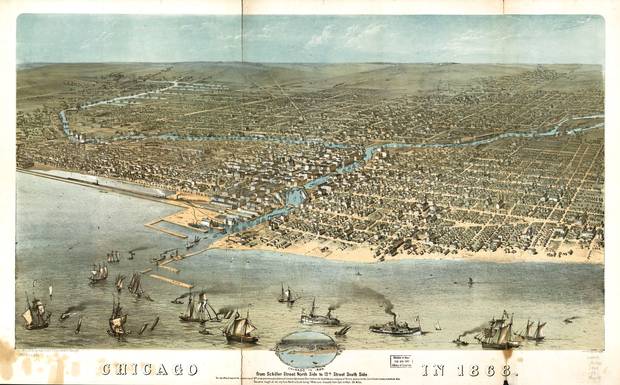

Chicago's Sunday bustle

Map of Chicago in 1868 from Schiller Street north side to 12th Street south side.

Library of Congress

Oct. 9, 1867 – In early October, 1867, a correspondent from The Globe, who happened to be in Chicago on a Sunday, reported breathlessly about the widespread commercial activity in that city. "The shop windows are not obscured by sombre blinds, but display their wares as temptingly as on a secular day." It was a big contrast to Toronto and other Canadian cities, where Sunday was a day of rest and almost everything was closed up tight. In Chicago, however, "the business streets are guiltless of any appearance of recognition of the Sabbath," The Globe's staff writer wrote. And there was no religious restraint: "At about the hour for people to congregate in the churches, an industrious farmer might be seen driving along with a load of hay, evidently looking upon this day as the one for doing odd jobs. Groceries, groggeries and saloons all seemed to be in full blast." – Richard Blackwell

Alaska skips 11 days

Harper’s Weekly

Oct. 16, 1867 – After the United States purchased Alaska from Russia in 1867,

Commercial Bank of Canada collapses

Oct. 23, 1867 – At the time of Confederation, there were dozens of small chartered banks in Canada, and some of them were in bad shape. In late October, 1867, the Kingston-based Commercial Bank of Canada ceased operating – the second collapse in a year, after the demise of the Bank of Upper Canada in 1866. The Globe insisted that the Commercial Bank's failure was not the fault of a depression, an inflation crisis or "unsoundness in the mercantile community of Upper or Lower Canada." Instead, "the origin of the evil may be summed up in one word – mismanagement." The main problem was a bad $1.8-million loan to a U.S. railway company. Among the shareholders that took a big hit were Queen's University's endowment fund and the Church of Scotland. In early 1868, there was some relief when the bank's shares were bought, at a steep discount, by Merchants Bank of Canada. – Richard Blackwell

Globe (tentatively) backs women in medicine

Herbert E. Simpson

Oct. 30, 1867 – In a late-October editorial, The Globe supported women going into medical practice, but with caveats. Women should be trained to "take care of the diseases of women and children and the various troubles and ailments which are peculiar to them," the newspaper said, but they should not be general practitioners. The editorialist wasn't keen on allowing women into other professions either, saying, "We are old-fashioned enough to think that female clergy, or lawyers, are not quite the thing." But the paper's traditionalist views were soon overtaken by events. Canadian Emily Stowe, above, finished a medical degree in New York in 1867 after being refused admission to the University of Toronto medical school. She returned to Toronto and became the first woman to practise medicine in Canada, although she had to wait until 1880 to get a full medical licence. – Richard Blackwell