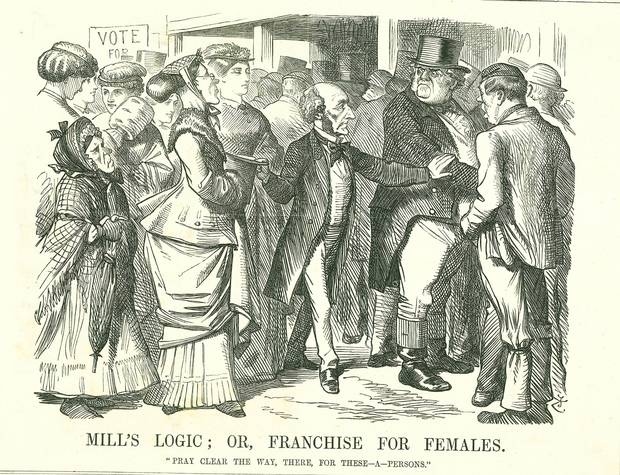

John Stuart Mill proposes women's suffrage

Universal History Archive/Getty Images

June 5, 1867 – The Reform Bill tabled in Britain's Parliament in 1867 was set to extend voting rights from just men who owned large properties to all male urban home owners and many lodgers. But philosopher John Stuart Mill rose in the House of Commons to argue that women, too, should get the vote. In his speech, reprinted on the front page of The Globe in the first week of June, Mill rejected arguments that politics would distract women from their duties or that they were sufficiently represented by male relatives. Forbidding women to get involved in issues of interest to men belonged "in a bygone state of society," when a wife was seen as plaything or servant, he said. "We ought not to deny to women what we [are] now granting to every class – the right to be consulted in the choice of a representative." Mill's amendment was defeated, and it was decades before women in Britain (and elsewhere) got to vote. –Richard Blackwell

The Globe blasts Macdonald

Toronto Public Library

June 12, 1867 – When Sir John A. Macdonald visited Toronto in June, The Globe and Mail – a staunchly anti-Conservative paper at the time – was quick to dump on the Tory leader. At City Hall, Macdonald drew a "poor turnout" and got a "feeble reception," the paper reported. An editorial described Macdonald's speech at the event as "nothing more than a miserable begging petition for the continuance in office a little longer of himself and his colleagues." It also suggested there was an "utter absence of policy" in the Tory camp for the future Dominion government, and that Macdonald was no friend of Ontario. "His whole course for 20 years past has been one of fierce hostility to the interest of Upper Canada," the paper insisted. Indeed, The Globe said, the new constitution set to come into effect on July 1 should not be credited to Macdonald but to "the arduous and self-denying labours of the Reform party of Upper Canada." –Richard Blackwell

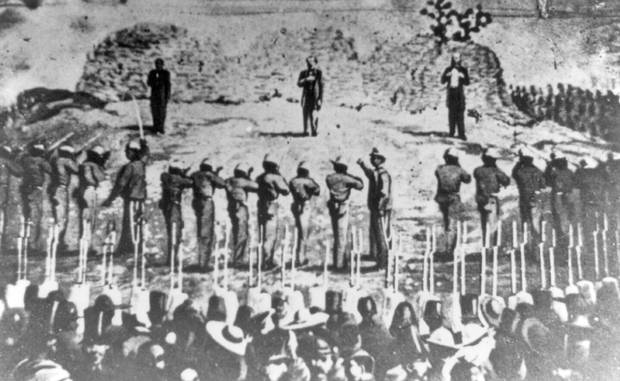

Mexico's emperor Maximilian is executed

Library of Congress

June 18, 1867 – As Canada prepared to celebrate its peaceful political transition, Mexico was in the throes of a more violent shift. On June 19, Mexican emperor Maximilian was executed by firing squad and a republican government restored to power. Maximilian, who was actually an Austrian archduke, had been installed by France's Napoleon III in 1864 after French troops captured Mexico City. But republican president Benito Juarez maintained widespread support while on the run, and he got military aid from the United States after the U.S. civil war ended. In mid-May, 1867, Juaez's troops captured Maximilian and he was shot a month later, despite international pleas for amnesty. The Globe decried the execution, saying in an editorial that "the republicans in Mexico have sullied their hard-earned laurels with the blood of Maximilian," who had earned much respect despite his "unwarranted assumption of the throne." –Richard Blackwell

Ottawa steps in to regulate Niagara Falls tourism

Library of Congress

June 26, 1867 – In the summer of 1867, the government of pre-Confederation Canada waded into a long-running dispute among entrepreneurs trying to make money from tourism to Niagara Falls. The Globe reported that Ottawa assigned a lease to museum operator Thomas Barnett, giving him exclusive rights to send visitors down his stairway to the foot of the falls. His archrival, Saul Davis, who had a reputation for fleecing sightseers, was excluded from the lease and Barnett was given permission to remove Davis's competitive stairs. The government, which controlled the land adjacent to the falls, also set prices "to prevent extortion such as has been practised on visitors." Barnett could charge tourists no more than 25 cents to descend his steps, or 50 cents with a guide. For $1, visitors would get a guide and "waterproof dress" to protect them while walking on a ledge underneath the falls. –Richard Blackwell