Looking through the darkness, Abdullahi Warsame fixes his gaze on the distant porch lights of a rural Manitoba house. After an arduous 11-month journey that spanned three continents and a dozen countries, the Somali man is just a short walk from Canada – less than a kilometre now.

It's 3:05 a.m. and eerily quiet as he trudges along the deserted highway in northern Minnesota with a cousin and a friend, all three from Somalia's war-torn capital of Mogadishu. In his left hand, Mr. Warsame is clutching court documents for a pending asylum hearing in Minnesota that he won't attend. The 45-year-old former cloth salesman is afraid of the new U.S. President, concerned about his plans to ban citizens from travelling to the U.S. from a number of Muslim-majority countries, including Somalia.

Lul Abdi Ali, her face covered, struggles to walk beside Mr. Warsame after the long trek. She's tired and cold. Delmar Xasan, the youngest of the three, in his late 20s, fled Somalia when al-Shabaab jihadists killed his brother. Mr. Xasan says they'll kill him if he goes back to Somalia.

Asylum seekers Abdullahi Warsame, Lul Abdi Ali and Delmar Xasan.

For years, Mr. Warsame had aspired to the American Dream and risked his life for a chance to make it in Minneapolis. But he struggled to find a job and the increasingly heated rhetoric about Muslims scared him. Walking this Midwestern highway in the hours before dawn, as his breath hangs in front of him and the temperature hovers just above freezing, his eyes are focused on a final shot at freedom – Canada.

They travel without luggage: The three had to abandon their bags the previous day during a failed attempt to cross along the banks of the Red River. They have little more than the clothes on their backs.

"Canada a very good country," he says in halting English. "In the U.S., there are no jobs, it's no good. We had to go to Canada or back to Somalia."

A kilometre shy of the border, an American customs agent in an SUV spots the three Somalis walking in the darkness. The SUV surges forward and stops beside the asylum seekers. The customs agent begins questioning them in the glare of the headlights. He wants to see their documents, but it's too hard to read the detailed papers on the side of the dark country road. The agent needs to know if they have any outstanding warrants, so he loads them into an SUV and quickly escorts them back to the nearby town of Pembina, N.D. The lights of Canada recede in the rear-view mirror as the car pulls away.

Refugee claimant Asha Ahmed came to Canada two months ago. She was once the acting minister for women’s rights for Puntland state in Somalia, before her life was threatened by al-Shabaab. She now lives in Winnipeg while she waits for her refugee claim hearing. Here, she cleans up after lunch in the apartment that she shares with other asylum seekers.

Yahya Samatar, from Somalia, works as a fundraising co-ordinator at Creaddo Group in Winnipeg. He first came to Canada in August 2015, by hiking and swimming north in the Red River. Since then he has been granted refugee status and sends money home to to support his family.

The border

On the third weekend of February, The Globe and Mail followed 22 asylum seekers who crossed the American border into Canada near the town of Emerson, Man. Other would-be asylum seekers from towns and cities in the U.S. also made the crossing at the border in Quebec. Like Mr. Warsame and his friends, who expected their travels to end in the U.S., they headed to Canada as a last resort. This final, and potentially perilous leg of their journey, owes much to a refugee agreement negotiated between Canada the United States more than a decade ago.

Signed in the wake of the Sept. 11, 2001 terror attacks, the Safe Third Country agreement requires that a refugee claim be heard in the country in which an asylum seeker first arrives. If that claimant applies for refugee status at a port of entry in a second country, he or she will be quickly returned to the first country.

Asylum seekers headed to Minnesota's northern border know that the Safe Third Country agreement applies to them only if they cross at the border station at the end of I-29. It doesn't apply to them if they cross illegally. Once their two feet have landed in Canada, they have the right to a refugee hearing.

There are risks to a covert crossing. Seidu Mohammed, a Ghanaian refugee, almost died during a trek on Christmas Eve. He lost all his fingers and a toe to severe frostbite.

Many of the refugee claimants who crossed illegally on the weekend of Feb. 18 said they were aware of the risks but knew it was the only way to circumvent the Safe Third Country agreement.

The number of asylum claimants from all countries into Canada reached a record of 36,867 in 2008 and declined over the following years. As of Feb. 13 this year, Canada has received claims from 3,802 asylum seekers, including those who have crossed the border illegally.

Here in southern Manitoba, many would-be asylum seekers said that taxis had dropped them off more than four kilometres from the border, west of Emerson. Left alone at the edge of rutted dirt roads, they are told to walk through fields of waist-deep snow to reach Canada. Their target: dozens of flashing red lights on the horizon, a wind farm in Manitoba.

The wind farm on the Canadian side the border, shown in daytime.

Once they cross the unmarked border, they're in a largely unoccupied stretch of Canada. There is little traffic and few farmhouses. During a cold snap, it can take hours to find someone to call the authorities for help.

Standing in the fields, they can hear the sounds of traffic and see the bright lights of the modern border station to the east. Dogs bark in the distance.

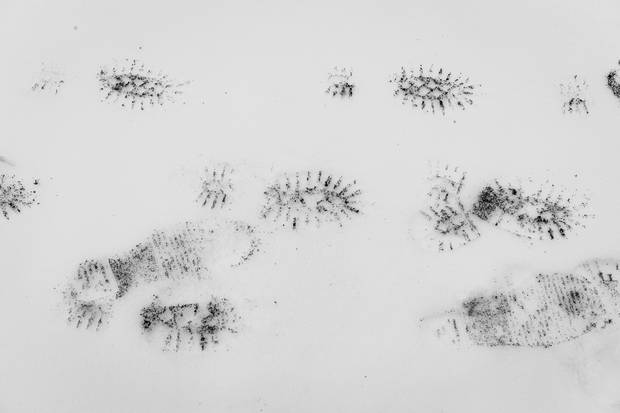

The snow is flat and crunchy. Within a few steps, they will sink up to their knees, sometimes to their waists. Their boots will quickly fill with snow, and their toes start to freeze. It's exhausting, lifting each leg straight out of the snow and coming down like a steam shovel. In the quiet of the winter night, crossing into Canada is a lonely act.

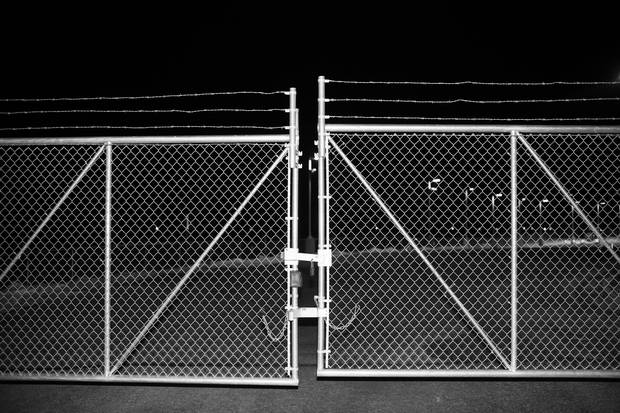

While some of the asylum seekers follow the Red River to the border, most opt for the easier route taken by Mr. Warsame's group, which ends in the centre of Emerson. That passage follows a largely deserted highway to the shuttered border stations that had linked central Manitoba with Minnesota for decades. There, all that blocks them from their destination is a yellow gate and a snowbank.

Two asylum seekers, a woman and young girl, cross the Canadian border, in Noyes, Minn.

Abandoned clothing lies along the train tracks.

An exhausted asylum seeker, bogged down by heavy snow, crosses the Canadian border in Noyes.

6 a.m.

After Mr. Warsame's group is led away by the American border patrol, the only sounds are a strong wind and the quiet chugging of a locomotive idling at a nearby rail crossing. Just before 6 a.m., several clusters of men, women and children walk quietly down the same road. With dawn only an hour away, they're trying to get to Canada before the first rays of light make them easy to spot.

At the front of the group, four young men see two reporters and scatter into nearby trees. They're only steps from the border. They then run directly to the yellow bar across the road and are in Canada moments later, walking into the sleeping town of Emerson.

A second group continues to march down the road. They're from Djibouti and speak French and Arabic. "This is because of Trump," the first man of this group says loudly in French. "We don't want to be here."

He's breathless, yelling "fast, fast" to his group. They travelled up from Minneapolis by taxi and walked for nearly five hours to the border. "God help us. We've been walking for hours. It's slippery and I'm so tired, so exhausted," said one man in his early 20s. He declined to provide his name, fearful of what would happen if authorities found him.

There are seven in his group. He carries a heavy backpack; the straps are cutting into his arms. He drops it momentarily and waits for the rest of his companions to catch up to him. He beckons them on in Arabic to move faster; they're close to Canada, he tells them. He then confides to a reporter that he doesn't know the way but is only following nearby railroad tracks. One of the men in his group has a six-month-old baby in a scarf wrapped around his chest. The baby is sleeping.

Two other men remain quiet during the walk, while a woman in the group gently but urgently pulls her two-year-old daughter by the arm.

The man critical of Mr. Trump says they've been told to cross along the railroad tracks. It's safer. They need to walk over a small hill and alongside a station building painted with the letters BNSF – the name of a railroad network – painted on the side. A train crew is inside, lights on, unaware of the people filing past outside their door.

As the travellers reach the top of the hill, they spot three fawns grazing on the tracks. "Are they wild animals?" the man asks. "Are they dangerous? Will they attack us?"

Beyond the deer, he sees the equipment that customs crews use to inspect rail cars and is told he's at the border. His eyes go wide and he stops, setting down his bag again. "There are no police," he says, the relief clear in his voice. He urges the rest of his group to speed up. "God bless Justin Trudeau, God bless all Canadians," he says with excitement.

The group move quickly along the track. The two-year-old, wearing a silver coat, walks playfully along a single rail with her arms outstretched. Her mother tells her to stop. A few steps later, and they're in Canada.

Ten minutes later, another group of five people approaches the border at the same spot. One of them, a 30-year-old Somali man, says he has been in the U.S. for seven months but his refugee request has been denied. "I'm concerned that they'll send me back to Somalia," he says, declining to provide his name. "I hope Canada will let me stay and let me live free."

A woman in his group stumbles as they reach the snowbank that marks the end of their struggle out of the U.S. Her young daughter also falters. The woman's face is twisted in agony as a man picks up her child and carries her through the knee-high snow to Canada.

The woman is walking in leather slippers and her feet are caked in snow. She pulls one slipper off and dumps out the snow.

In the distance, they see a car approaching. The men, fearing that it is the border patrol, start yelling at the woman in slippers to keep moving. She starts crawling through the snow, slowly, painfully. After a few metres, she gets to the yellow gate, stops momentarily before she starts crawling again, over the border. Her daughter has already made her way into a country the woman hopes will give both of them refugee status.

By dawn, 16 men, women and children have crossed into Canada along this route. All of them have been picked up by RCMP officers within minutes of arriving, ushered into a minivan and driven to a nearby border station for medical care and to begin the process of requesting refugee status in Canada.

The first light of the day shows a trail, kilometres long, of items discarded in the dark. Blue baby booties in the middle of the road. A red woman's scarf on the railroad tracks. A brown scarf is snagged on the rails. Two bags have been dropped, both filled with women's clothes.

A red scarf is left behind after the asylum seekers’ scramble at the border.

Minneapolis

For many would-be refugees, the journey to Canada starts in Minneapolis's neighbourhood of Cedar-Riverside. An area east of the city's downtown, where mosques sit beside bars, it's been nicknamed the Ellis Island of Minnesota by locals, and Little Mogadishu by others. The inner-city neighbourhood contains the largest concentration of the state's nearly 100,000 Somalis.

At the centre of the area is Riverside Plaza, a complex of six soaring apartment buildings with more than 1,300 residential units. Many Somalis find their first apartments in the complex, according to community activist Abdirizak Bihi.

"The Somali community is tightly knit, everyone knows everyone," he says. There are about 40,000 Somalis in the city.

In the yard at the centre of the complex, six Somali youth play football. As the community has become more established and wealthier, more Somalis have left Riverside Plaza for the affluent suburbs.

While many of the Somalis who head to Canada have stayed at the complex, few have told the locals what they were up to. "People are scared of Trump," Mr. Bihi says. He said the refugee claimants were worried their friends or family could get in trouble for harbouring them.

Wali Dirie, the executive director of the Islamic Civic Society of America, has heard of the young men going north, but none have asked the mosque for help. That doesn't surprise him. "Somalis help each other," he said. "Even if you don't know someone, you've got a cousin or uncle who does. This is a big family."

Leyla Qurey, Deeqo Qurey, Fadumo Hussein and Susu Hussein gather at a local Starbucks.

At the area's Starbucks, dozens of Somalis fill the coffee shop from dusk to dawn. Besides the mosques, it's the community's main gathering place, where they can gather to gossip, conduct business and share laughs. The parking lot outside is mayhem, with groups of men milling about as cars navigate around SUVs that are double and triple parked.

There's a policy of don't ask, don't tell. Members of the community shelter relatives and friends without question and no explanation is expected when they're gone.

Many in the Somali community are proud of their American citizenship, openly brandishing their citizenship cards when speaking with reporters and loudly declaring their allegiance to the U.S. But after a few minutes of conversation, they allow that they are concerned about Mr. Trump and would begrudgingly consider fleeing to Canada if things continue to worsen or the ban on Muslims return and is made permanent – which could affect friends and family members.

"A lot of people are struggling. Canada is just better when you aren't welcome here," says Abbie Ahim Ali, who has lived in Minnesota for 17 years.

The hours-long drive from Minneapolis to the northern border stretches through kilometer after kilometer of monochromatic brown prairie interrupted by the occasional small town. Buses stop in Fargo and Grand Forks in North Dakota. Closer to the border, long trains and looming industrial complexes break up the monotony. There hasn't been any bus service between the Midwest and Winnipeg since 2010; the only route takes three days and goes through Toronto.

Many of the refugee claimants take a taxi from Grand Forks one hour north to Pembina and walk from there. Cab drivers in Grand Forks quoted a price of $145 to $180 (U.S.) for a drive to the border, but added that they had never driven Somalis to the border. Many Somalis reported fares of up to $900.

Somalis gather after Friday prayers outside the mosque in the Cedar-Riverside neighbourhood of Minneapolis.

The agreement

The Safe Third Country agreement emerged at a time when the American government was particularly concerned with border security. Canada and the U.S. pursued the deal as part of a perimeter security concept, which was aimed at shifting resources away from the Canada-U.S. border in order to increase the scrutiny of people coming from other countries.

Because the agreement was introduced in Canada through regulations rather than as a stand-alone piece of legislation, the measures received limited debate on Parliament Hill. MPs on the immigration committee held several days of hearings on the agreement in late 2002, which immediately exposed some of the problems the current Liberal government now faces.

Specifically, the deal only applies to asylum seekers who appear at official ports of entry, such as border crossings and airports.

Refugee advocates, including Amnesty International and Judith Kumin, the former United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees' representative in Canada, all warned at the time that this would encourage asylum seekers to attempt other more dangerous ways to cross the border, possibly with the assistance of human smugglers.

Senior government officials acknowledged this possibility at the time but offered no clear explanation of that aspect of the deal or how it would be managed. "An agreement like this will mean people will look for alternative ways to seek entry to Canada and claim refugee status," said Joan Atkinson, an assistant deputy minister with Citizenship and Immigration, at the time. "So we are very cognizant of the fact that people will seek alternative ways. They will probably try to avoid going through the United States and come directly, if that's possible. As for smuggling across the Canada-U.S. border, as I said, it's very difficult for us to predict how much that will happen and whether there will be increases."

This aspect of the deal has recently been described as a "loophole" that encourages the risky border crossings that have increased since Mr. Trump's election victory.

Canada could arguably negotiate a change to the deal so that it applies to cases where people are picked up within a specific distance from the border, but Ms. Kumin says that would require a much higher level of border surveillance than is currently in place now.

In the current context, Ms. Kumin says Canada needs to look for trends among the asylum seekers now crossing the border to better understand the issue. It must also assess the policies of the U.S. government to determine whether Canada still views its neighbour as a safe country for refugee claimants.

"That's the fundamental question," she said. "I don't think it's that easy to answer right off the bat."

The flow of irregular crossings and the expectation that they will increase as the weather improves is now one of the main political issues on Parliament Hill. The NDP, which opposed the deal in 2002, continues to call for its elimination.

The Conservatives have not gone that far, urging the Liberals to come up with a plan. However, Conservative MPs have not put forward specific suggestions as to what Ottawa should do, beyond providing more help to the border communities in Quebec and Manitoba that are currently dealing with the rise in asylum seekers.

Liberal Citizenship and Immigration Minister Ahmed Hussen, who arrived alone in Canada as a 16-year-old refugee from Somalia, argued this week that there is no reason to suspend Canada's participation in the deal. He called the agreement an important tool.

"We will not get out of the Safe Third Country Agreement because the United States continues to meet its international obligations with respect to its domestic asylum system," Mr. Hussen told reporters Thursday. "I certainly sympathize with what people have to go through to seek safety and security. What I can tell you is once you're in Canada, you get access to a fair hearing, and your case is judged on its merits."

On the country road from Pembina, N.D., asylum seekers are instructed to walk toward the wind turbines on the Canadian side.

A U.S. Customs and Border Protection officer on patrol near Noyes, Minn.

The Neche/Gretna border crossing near Pembina, N.D.

A residential building near the border between Minnesota and North Dakota.

Border patrol

The local U.S. Customs and Border Protection supervisor filled up on soft drinks from the gas station in Pembina just after midnight. His agents had already intercepted three asylum seekers that evening, but they were released after their papers were checked. In a few hours, he would apprehend Mr. Warsame and his group.

"This is starting to feel like a humanitarian operation," he says. The supervisor is set to move to the U.S. southwest border and asked that his name not be shared because he feared Mexican cartels could target him.

While there's a widespread concern in the Somali community that anyone caught headed toward the border will be deported, the supervisor said that isn't happening. His agents are only looking at identification documents to check for criminal records. Several people have been stopped and turned over to local authorities after outstanding warrants were found.

With asylum seekers losing fingers to frostbite, he says a lot of miscommunication is putting them at risk. He insists there is no need for them to walk through waist-deep snow. "We're getting [destroyed] by our media," he said.

Over several hours, he showed a Globe reporter and photographer where he searches for asylum seekers and pointed out the routes they can take. There are a number of paved roads that go right up to the border, especially around Emerson, where they can find immediate help from the local RCMP detachment.

Most refugee claimants told The Globe they were instructed by taxi drivers and smugglers that they couldn't approach the border and that they should walk through the fields to avoid detection. There's no law barring someone from driving up to the border, the CBP supervisor insists.

"The only snow they have to trek over is that little bit right there," he said, pointing at the 150-metre-wide snowbank separating the shuttered border stations on the road into Emerson.

A marker shows the Canada-U.S. border in Emerson, Man.

While many Canadians and Americans would like the patrols on both sides of the border to stop asylum seekers from breaching the undefended frontier, law enforcement on both sides face a Catch-22 that makes irregular crossings nearly impossible to stop under current circumstances.

U.S. border patrol can't interfere until asylum seekers break the law by crossing illegally, which means that they could yank a person back by the collar if they've got a foot in Canada, but once the second foot is across, they can't do anything, according to the supervisor. The window to stop someone is a second or two.

On the other side, RCMP officers say they can't interfere with asylum seekers until they cross into Canada, at which point they're on Canadian soil and have the right to request a refugee hearing. They told The Globe that they could hold out their hand and try to block someone who is still partially in the U.S. But that doesn't happen.

While the U.S. CBP can't legally point these people in the right direction to cross illegally, they can recommend that they stick to paved roads.

Delmar Xasan goes under a road block to enter Canada. He fled Somalia when al-Shabaab killed his brother, and says the jihadist group will kill him if he returns.

Lul Abdi Ali and Abdullahi Warsame climb through deep snow at the border.

Abdullahi Warsame

Just after 8 a.m., the community of Emerson has begun its day. Some Americans are now driving to work. On the Canadian side, people are out walking their dogs and seniors are strolling the streets of Emerson.

Three Somalis appear on the road in daylight.

It's Mr. Warsame and his two fellow travellers, the same group that had been detained earlier in the morning by the border patrol supervisor. Their documents checked out and they were released at the gas station in Pembina, N.D.

This is now their third attempt to cross in two days. They started along the Red River at 8 p.m. the previous day and the exhaustion is clear as their legs pump forward. While their clothes are a little shabby, the three are bundled up for the winter in knockoff parkas and cheap boots. They're all wearing warm hats, scarves and gloves.

Lul Abdi Ali and Delmar Xasan walk north toward Canada.

"They told me, you're free to go. You can go to Canada," Mr. Warsame says of the border patrol. For a few moments, a border patrol truck followed the group but kept driving without asking them any questions.

Mr. Warsame is struggling with his diabetes. His medication was in a bag that he abandoned along the river.

He has a wife and three kids back in Mogadishu. He wants to find a job in Canada and get to work, something that he said was challenging in the U.S.

He left Somalia last April 25 and travelled through 10 countries on his way to the U.S. After passing through Saudi Arabia, he reached the Americas via Brazil, walked, hitchhiked and bused his way through Central America and crossed the Mexican-U.S. border into California. He spent four months in an immigration-detention centre before his request for refugee status was heard. While he waited for his asylum hearing Mr. Trump was elected President.

"There are so many problems with Trump. I always wanted to come to America, I love America, but not any more, not with Trump," he says.

Staying with friends in Minneapolis for three weeks, he quickly decided that it wasn't safe any more to wait in the U.S. The three took a taxi cab to the area near the border for $600.

Just after 8:30 a.m., they walked past the former American customs post that lies derelict at the border. It's a charming brick structure that's listed as a heritage building, although now it's dark and quiet with all operations moved to the modern structure a few kilometres away.

Around the post are a clutch of abandoned buildings. The hamlet of Noyes is quiet; it has less than a handful of residents left.

In Noyes, footprints of migrating asylum seekers lead north into Canada.

Emerson, Man., has seen an influx of dozens of asylum seekers from south of the border in recent months.

Canada

It's early in the morning of Feb. 19 and Abdi, Omar and Naima are standing in the parking lot of the Maple Leaf Motel in Emerson. They're some of the only Somalis to cross that night and they're worn out after a rough walk through fields deep with snow.

They stayed away from roads to avoid detection. Abdi, 24, has lost all feeling below his knee.

"Canada is good, I feel free," he says after learning he has crossed the border. "In America, you can't sleep, you don't know if they'll deport you. You have to stay in the house all day, it's too unsafe to go outside."

Omar Ahmed, 30, falls to the ground with a grunt. He's in pain and quickly peels off his boots. His feet are covered in snow and frozen.

Asylum seeker Omar Ahmed tries to warm his frozen feet.

Omar and his companions trekked through heavy snow, away from roads to avoid detection.

Abdi, who asked not to share his family name, left Somali in 2013. He says that the U.S. has changed under Mr. Trump. "Everyone is getting denied [refugee status] in the U.S. It's very scary. They didn't schedule my hearing yet, but I know they'll deny me. That's why I went north," he says.

The three met in Minneapolis and split the $450 taxi fare north. Naima, 23, is covered in burrs after walking through ravines. She's dehydrated and says she's in pain.

Minutes later, an RCMP minivan arrives to pick up the three. The officers ask them if they need medical attention and quickly put them in the van for transport. "My right foot is very painful. Don't take me to the U.S.," Naima pleads with the officers. "They are taking me back to the U.S.," she says crying. The officers repeatedly tell them they aren't going back to the U.S., they're going to file their refugee papers.

Abdi jumps out of the minivan to make sure it doesn't have an American licence plate. Naima spits up a pool of blood.

"The situation is getting a bit extreme here," one of the officers says with a sigh as the van drives away.

As of Feb. 13 this year, Canada has received 3,802 asylum claims. Refugee advocates expect border crossings to increase in the warmer months ahead.

Justin Giovannetti is The Globe and Mail's Alberta reporter. Follow him on Twitter: @justinCgio

With reports from Bill Curry in Ottawa

MORE FROM THE GLOBE AND MAIL

NDP calls on Trudeau to end refugee agreement with U.S.