On the evening of May 6, 2005, a farmer near Sherwood Park, Alta., just east of Edmonton, was preparing a stubble field for cultivation when something out of the ordinary caught his eye. Through his filthy windscreen, he spotted a pale mass in the distance, faintly illuminated by his tractor's headlights. Unsure of what he was seeing, he got out of his tractor and stood on the tire, then clicked on his flashlight, sweeping its beam through the darkness. What he was looking at, he eventually realized, was a pair of grey sweatpants. They cloaked a partially decomposed body.

The farmer called the RCMP, then parked alongside the highway to await their arrival.

Investigators conducted a perimeter search the following morning. They placed paper bags over the head, hands and bare, dirty, straw-covered feet to preserve evidence. Two days later, the medical examiner would determine that the victim, Ellie May Meyer, had died from multiple head injuries. Her pinky finger was missing; he suspected an animal had chewed it off. He guessed she'd been in the field for weeks. The Edmonton Journal related the Quebec-born 33-year-old's journey from would-be nurse to mother, sex worker and finally, tragically, homicide victim.

MURDERED

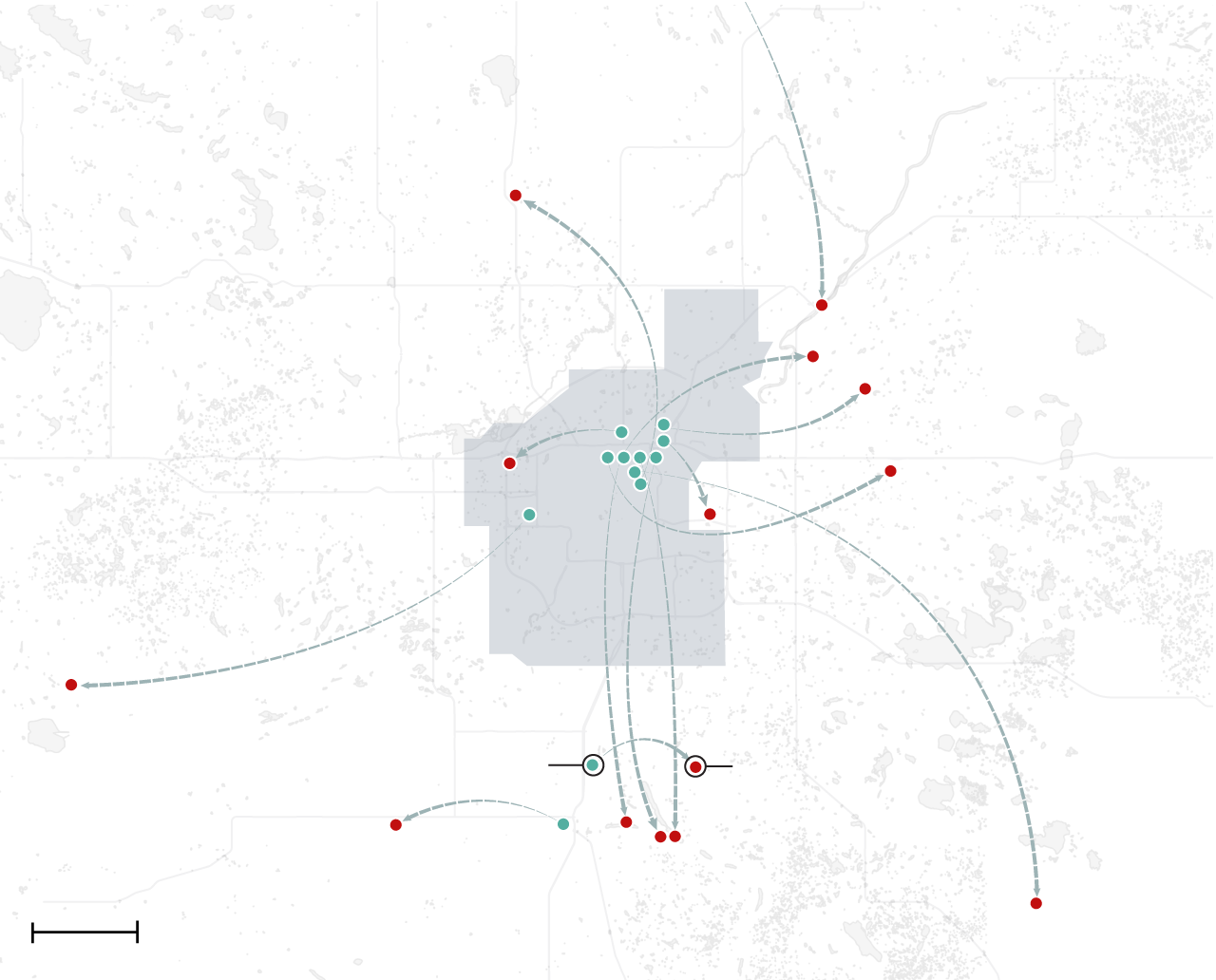

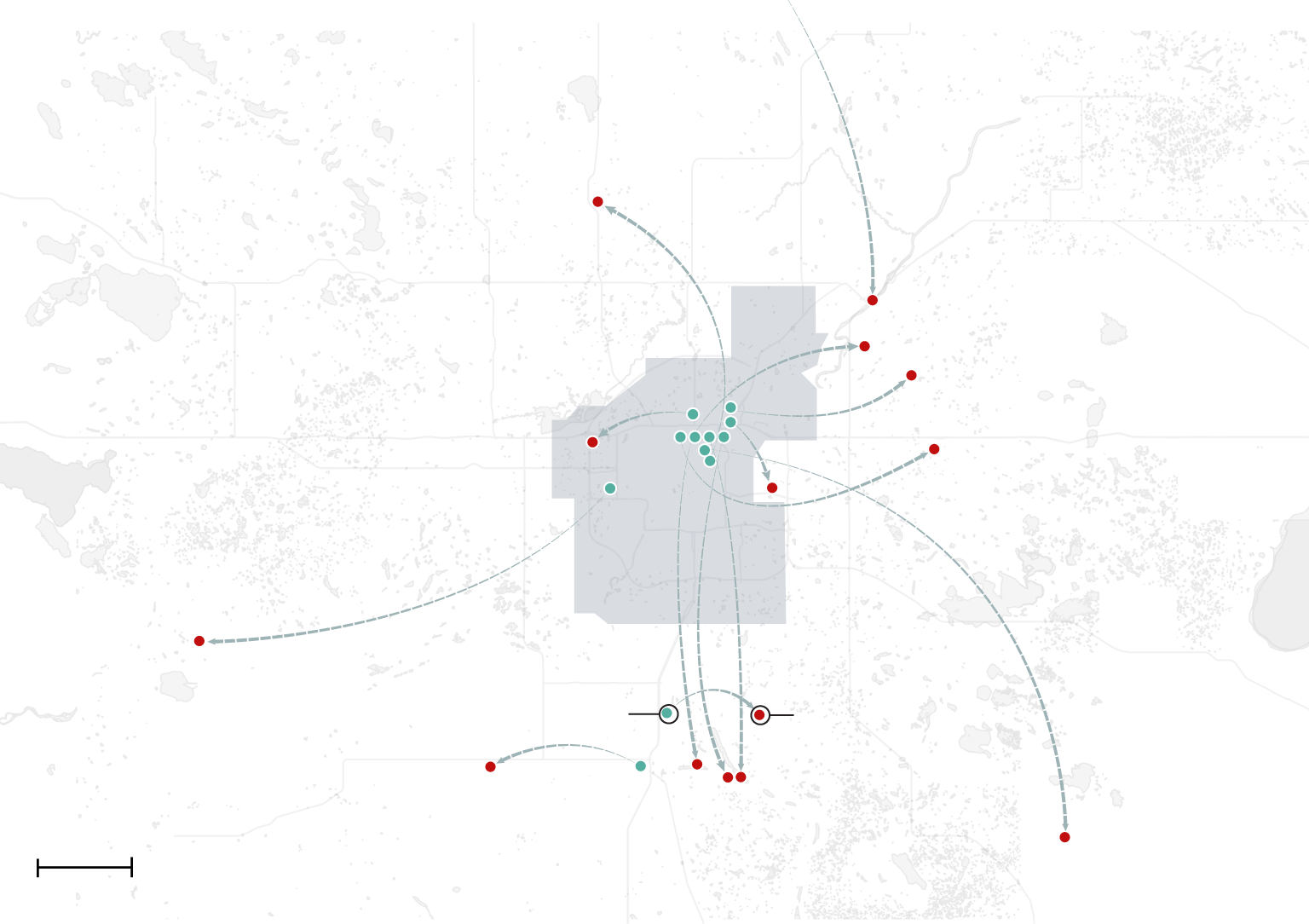

Hers was not an isolated case, as Inspector Mike Sekela knew. Edmonton had a problem. During the previous two decades, the city and surrounding communities had witnessed dozens of eerily similar crimes. A massively disproportionate number of the victims were indigenous. Most were sex workers. Some were homeless. A few were children. The remains of many turned up in ditches, fields and forested areas beyond the city limits – circumstances that led many observers to conclude that serial killers were preying on local women.

Discovering whether this was true and, if so, to what extent, was Insp. Sekela's mandate. As team commander of Project KARE, an initiative devoted to serial-homicide investigations, he had an important determination to make about Ellie May Meyer: He needed to judge, using the limited information before him, whether Ms. Meyer was the victim of a serial predator. If so, KARE would add her name to its already lengthy roster. If not, it would pass the case to other local RCMP units.

The decision facing Insp. Sekela carried high stakes, not simply because he was in the business of solving homicides, but because he was heading a new enterprise that hoped to redress shortcomings in policing following the Robert Pickton debacle. When the Vancouver-area serial killer was finally charged, Project Evenhanded, the RCMP and Vancouver Police's joint force that ultimately captured Mr. Pickton, came under fire for failing to protect the public; critics said Evenhanded's poor handling of cases meant lives were needlessly lost. KARE wanted to learn from Evenhanded's mistakes. It wanted to restore the public's faith in policing.

Whether it succeeded remains an open question.

This week, the federal government launched a national inquiry to investigate systemic causes of violence against indigenous women and girls in Canada. The RCMP and other police forces across the country will likely receive criticism from the community that KARE had hoped to work more closely with.

During preinquiry consultations in Edmonton in February, family members and friends of victims spoke about unclear processes in filing missing-persons reports, about insensitive treatment by police, and about long periods of silence during which police communicated nothing at all. Some of these criticisms may be levelled at KARE in the coming months.

KARE's biggest disappointment, though, was that, despite its dedication to innovation and rigour, it was able to identify only a tiny fraction of the offenders responsible for Edmonton's many unsolved female homicides and bring them to justice. Was this the result of a flawed initiative? Or is the disturbing truth that, however rigorously and faithfully they're employed, best practices remain insufficient to crack some of the country's most troubling crimes?

Citing the continued need to preserve the integrity of ongoing investigations, Insp. Sekela today declines to reveal what he observed that day in the stubble field. He acknowledges that some of his colleagues thought that KARE should take up Ms. Meyer's murder: She was, after all, a sex worker found east of Edmonton. But Insp. Sekela wasn't convinced that it was part of the crime series his team was investigating. "The scene was different, the circumstances surrounding it were all different," he says. Finding no clear indications of serial murder, KARE left the investigation to Sherwood Park RCMP.

Insp. Sekela's intuitions were, in hindsight, only partly correct. Ms. Meyer's murder indeed differed materially from others that KARE investigators were pursuing. What he couldn't have foreseen is that it was actually the first known murder in a new series. Or that the perpetrator had already killed again.

The case of Ellie May Meyer would return to KARE in a manner he couldn't have anticipated.

In the hunt for predators, the first stop is the street

In 2002, at the time of Robert Pickton's capture, Mike Sekela was working as an intelligence officer for K-Division, as the RCMP's Albertan presence is known.

Leading up to Mr. Pickton's arrest, women had been disappearing from Vancouver's impoverished Downtown Eastside for years. Yet the Vancouver Police Department's management refused to acknowledge the possibility that a serial killer might be responsible. Project Evenhanded incorrectly assumed that women had stopped disappearing. Mr. Pickton was eventually convicted of six counts of second-degree murder, but DNA from dozens more missing women were found on his farm. Shortly after his arrest, Mr. Pickton told an undercover cop that he'd murdered 49.

Although Mr. Pickton's crimes occurred more than 800 kilometres from Edmonton, they resonated in a city in the throes of its own disappearances. K-Division Chief Superintendent Gord Button visited that fall with his B.C. counterparts and sought out Insp. Sekela upon returning to Alberta. "He asked what was going on in the province of Alberta in relation to missing aboriginal women," recalls Mr. Sekela.

That question would consume the next several years of Insp. Sekela's life.

Murder of any kind is a profound tragedy for the friends and family of the victim, but for police, serial homicides present a particular challenge. Failing to respond appropriately to a series of related murders typically attracts public scorn, and is often followed by withering public inquiries.

Yet, linking cases in real time is no simple task. Commonalities such as how victims were selected and where their remains were discovered may reveal patterns in offenders' motivations and behaviour, but serial killers do not always behave consistently. And when victims' disappearances remain undetected for weeks, police begin their investigations at a significant disadvantage. Insp. Sekela hoped to fold into this already challenging mission an improved social component as well, taking into account the particular sensitivities needed when dealing with a community of sometimes rightly distrustful marginalized people.

Insp. Sekela began mustering resources to find an answer to the question of Alberta's missing indigenous women. He first broadened his scope, assigning a crime analyst to study the cases of all missing women in the province – of any ethnicity – deemed to have lifestyles leaving them vulnerable to violence. This exercise was dubbed the High Risk Missing Persons Project. Its first task was to modernize relevant files concerning approximately 80 homicides and missing-persons cases from across Alberta and to put the information into a database. RCMP analysts then looked for possible links between cases, such as common vehicles and phone numbers.

The large number of victims in and around Edmonton stood out immediately.

Insp. Sekela then asked the RCMP's Behavioural Sciences Branch in Ottawa to review a handful of cases. Consulting crime-scene evidence, the RCMP's behavioural analysts created an offender profile, concluding that five street-sex workers found murdered outside Edmonton in 2002 and 2003 had likely been killed by the same person. The killer or killers, they said, would continue to frequent sex workers and to murder some of them, possibly also seeking targets outside the sex trade.

This information was enough to spur Insp. Sekela and K-Division's senior management to create a new unit to hunt serial predators. Project KARE was born in October, 2003, with Insp. Sekela as team commander. He appointed a veteran homicide detective, Staff Sergeant Kevin Simmill, as lead investigator. Staff Sgt. Simmill had been part of an external team that reviewed the conduct of RCMP personnel and detachments during the investigations into Mr. Pickton and related missing-person cases.

It was to be a serial-predation squad the likes of which no city in Canada had witnessed before. Nonetheless, at KARE's inception, "we didn't have a building," Insp. Sekela recalls. "We didn't have a car. We didn't have anything."

What they did possess was considerable knowledge of what had gone wrong in Vancouver.

Gaining the trust of 'live victims'

Amid public outrage following the Pickton arrest, the Vancouver Police Department's and RCMP's investigative black boxes were pried open. When, finally, a commission of inquiry was convened to study the Pickton debacle in detail, headed by former judge Wally Oppal, he found that police had ignored or misinterpreted early signs that large numbers of women were disappearing. Many families had encountered barriers while attempting to report missing women to the VPD, or complained of disrespectful treatment. The VPD had also been resistant to, even contemptuous of, emerging techniques that might have advanced its investigations.

"I conclude that the missing and murdered women investigations were a blatant failure," Commissioner Oppal wrote in his final report. "The lack of urgency in the face of mounting numbers of missing women from a small neighbourhood was unreasonable at the time and is frankly astonishing." Although Commissioner Oppal's report wasn't published until 2012, many of its conclusions were already evident at the time of KARE's formation.

Insp. Sekela studied that and other serial-homicide investigations, and incorporated the latest thinking into Project KARE. He requested a staff of 46 officers, from investigators to crime analysts to DNA specialists. He seconded officers from other agencies; beginning in 2005, the Edmonton Police Service supplied several members to work in KARE's downtown offices. To avoid gaffes that could sink court prosecutions, he requested that KARE be assigned its own dedicated Crown attorney. KARE secured provincial and federal funding totalling several millions of dollars annually.

Still, Project KARE hungered for better street intelligence. It needed to know who worked Edmonton's strolls (streets with high sex-trade activity), which johns exhibited violent or deviant behaviour, and who often seemed to be hanging around just before women disappeared. So Insp. Sekela assembled what he called an "Insurgence Team" (later rebranded the "Pro-Active Team"). Members began patrolling Edmonton's strolls and building relationships of trust with sex workers. "There's a lot of times where these cases have what I call a 'live victim,' where someone would escape from the predator or predators," Insp. Sekela says. "They're out there, they may just not have been talked to."

Officers also collected DNA and personal information, to be used exclusively to identify sex workers' remains or help find them in the event they disappeared. Ellie May Meyer was among the many who registered.

KARE considered virtually every individual who purchased sex on Edmonton's strolls to be a person of interest; Staff Sgt. Simmill says that KARE learned about thousands of them from sex workers, social agencies and other sources. Behavioural analyst Larry Wilson, who'd previously worked on the investigation concerning team serial killers Paul Bernardo and Karla Homolka in Ontario, created the Person of Interest Priority Assessment Tool (POIPAT), which compared these individuals to the RCMP behavioural profile and assigned a priority score of 1, 2, or 3. KARE investigators worked through them in ascending order.

Some social-services agencies were pleased by the improved rapport between the police and sex workers. KARE was "a whole different way of policing," says Kate Quinn, executive director of the Centre to End All Sexual Exploitation (CEASE), a community group that seeks to reduce demand for sexually exploited persons. "The women, they had nothing to fear from Project KARE officers, because they weren't there to arrest them."

The unit also developed what Commissioner Oppal described as a "highly efficient" system for exchanging information with social agencies. This "fan-out" system enlisted street outreach workers, hospital employees and others to help police locate missing persons more quickly. Mr. Oppal says that lives would have been saved had KARE's practices been applied in Vancouver during the 1990s.

"Clearly it was a step in the right direction," he says .

Insp. Sekela's plan anticipated arresting its first suspect within three years. Foreign experts, invited to KARE's offices in downtown Edmonton to provide insights and advice, enthused to local newspapers that they were impressed by what they saw. Insp. Sekela, too, recalls having the greatest confidence in his hand-picked team. "We're solving this," he remembers thinking. "There's no question."

Kari Thomason, a support worker with the Métis Child and Family Services Society, drives her Jeep down Edmonton’s strolls and the dark alleys behind them, offering sex workers food, bad-date lists and other necessities, and recording where and when she spots the women. ‘This,’ she says, of 118th Avenue, ‘is referred to as Death Row.’

Amber Bracken for The Globe and Mail

'She just seemed lost'

For Kari Thomason, many of the disappeared were more than just names. A support worker with the Métis Child and Family Services Society, she goes out nightly, driving her Jeep slowly down Edmonton's strolls and the dark alleys behind them, through parking lots of seedy hotels. She pulls up alongside nearly every sex worker she sees, offering food, bad-date lists and other necessities. All know her and many trust her, although they eye the reporter riding shotgun with suspicion. Some are visibly agitated, likely suffering early stages of drug withdrawal.

She turns right onto 118th Avenue from 95th Street late one February evening, in the epicentre of Edmonton's unofficial red-light district. "This," she declares solemnly, "is referred to as Death Row."

She spots a sex worker walking on the south side of 118th. She dutifully records each sighting in a log book: first and last name, the nearest intersection, and the time. At the corner of 118th Avenue and 69th Street, one sex worker listens politely but noncommittally as Ms. Thomason urges her to take legal action against an abusive boyfriend. She gratefully accepts a pair of mittens. "I need to get sober and straight again," she says in a distant, weary tone.

A decade ago, during the worst years of Edmonton's "killing fields," as The Globe and Mail described Sherwood Park, disappearances from Edmonton strolls were sometimes separated by mere days. Stephanie Harpe, now a successful musician and mom, met some of the victims during a period of her life darkened by addiction. She recalls meeting Delores Brower – whom she knew by her street name "Spider" – in the late 1990s. The two lived in the same neighbourhood around 107th Avenue, then a hive of gang activity. "Everyone needs a place to use, so she started coming over to my mom's place," Ms. Harpe recalls. "We'd use there. We were just hanging out, going to the bars along the avenue."

Ms. Harpe recalls meeting Samantha Berg in the early 2000s at a bar on 124th Street. They became friends. In Ms. Harpe's estimation, Ms. Berg seemed ill-suited to street life. "She was a nice, sweet girl," Ms. Harpe says. "She just seemed lost." But Ms. Berg would try any narcotic, and her addictions worsened. "Behind addiction is always pain," Ms. Harpe says. "I didn't know what her pain was. We would never talk about things like that."

In about 2003 or 2004, Ms. Harpe says that the man she now calls her husband – himself a recovering alcoholic – pulled her back from Edmonton's abyss. "I just stopped seeing everyone," she says. "I changed my friends, I changed my environment." She learned of the tragic ends of her former friends from afar.

The last time anyone reported seeing Ms. Brower was on May 13, 2004, on the corner of 118th Avenue and 70th Street. Corrie Ottenbriet, another familiar face along the strolls, had vanished just a few days earlier; members of KARE's Pro-Active team were the last people known to have seen her, at 118th Avenue and 84th Street. By Christmas, another woman, Maggie Burke, had disappeared.

Police wouldn't learn of Ms. Brower's disappearance until nearly a year after the fact. By then, thawing snow had exposed Ms. Berg's frozen body in a parking lot.

Kari Thomason and the executive director of Métis Child and Family Services, Don Langford, attended Ms. Berg's funeral, accompanied by one of their clients: Charlene Gauld had been a close friend of the deceased. "She was crying," recalls Ms. Thomason. "She was like, 'Kari, I'm done. I'm not going to go back.'" An oil-services worker found Ms. Gauld's burned body in a wooded area southeast of Edmonton one week later.

Pressure on KARE's investigators – from both the public and from the participating policing agencies – mounted with each death. It was then that Mr. Simmill recalls reading a newspaper article that dubbed Sherwood Park "the killing fields." He lived there at the time. "It's not a nice thing for the community," he says.

CEASE's Kate Quinn says that Edmonton's unrelenting violence weighed on KARE members she knew. "They all felt terrible that they couldn't stop it sooner," she says. "They were pursuing one line of investigation, and then another woman would be murdered. They'd issue another press release, and they would be supporting another family."

Killers who follow no rules

Police solve most murders, but then most murders are comparatively easy to solve. Most killers have obvious connections with their victims, such as family ties, business dealings or at least an acquaintance of some kind. Investigators often work such cases "outward" from the victim, a process which can help identify suspects quickly.

Yet, in cases where perpetrator and victim barely know each other – a feature of many serial homicides – this approach yields little. "Instead, the factors that link the cases are the offender and the choices he makes in the commission of his murders," noted a 2014 monograph from the U.S. Federal Bureau of Investigation examining serial-homicide investigations. So investigators must amass and sift through haystacks of crime-scene and other evidence, looking for links among potentially hundreds of suspects.

Homicide investigations should commence immediately following the crime, while witnesses' memories and forensic evidence are fresh. Yet serial predators sometimes conceal their victims, delaying discovery. As a result of decomposition, Mr. Simmill says, in most KARE cases there was hardly any forensic evidence.

Compounding the problem, many of the missing women were part of a vulnerable population, which meant that their disappearances were not reported immediately, or, in some cases, were overlooked by police. The Globe collected data on 49 female homicides in Edmonton, between 1986 and the present, in which remains were found outdoors. For 21 cases, we had information on the date the person was last seen and the date the person was reported missing. The median time elapsed in these cases was 27 days; in two extreme cases, the woman was not reported missing until years later.

Sometimes, such delays reflect the nature of the sex-trade and drug subcultures. Both are secretive by nature; participants may habitually disappear for days or weeks at a time, or have irregular contact with their families, so it might not occur to others to report their final disappearance to police until well after the fact.

However, police themselves can also create delays. Some victims' families have reported difficulties convincing police to accept missing-person reports.

In 1997, Cara King's mother spoke to the Edmonton Police Service about her daughter's disappearance several times, but later learned the force hadn't even opened a file. A farmer discovered Cara King's remains while harvesting his crop.

KARE's most important feature, Kathy King says, is that it took disappearances more seriously.

Wire, and human remains

In June, 2004, RCMP officers were dispatched to a small stand of trees east of Edmonton. In a clearing strewn with old lumber, vehicle parts, tires and a chesterfield, they found a body. The victim was identified as Rachel Quinney, a mother of two toddlers. She was last seen working the 118th Avenue stroll. The medical examiner later testified that, based on the deteriorated evidence available to him, "the cause of death of this individual remains undetermined." Her death was treated as a homicide.

Police did not happen upon her by chance. Thomas Svekla, a sometime auto mechanic with a lengthy criminal record, directed them to the spot. According to one court document, he told the RCMP that he'd happened upon Ms. Quinney's remains during a cocaine-fuelled partying binge. He'd waited a week before reporting it to police, fearful, he said, that he'd become a suspect.

The RCMP were indeed suspicious of Mr. Svekla, a serial sexual predator who, in 1993, had been convicted of the assault of a sex worker along one of Edmonton's strolls. Beginning with a minor theft charge 20 years earlier, Mr. Svekla had amassed a lengthy criminal record. He had a history of assaulting girls, the youngest of whom was five years old. A psychologist would later describe him as a "highly psychopathic violent offender who represents a high probability of committing further acts of violence."

But helicopter surveys of the crime scene, tire-print impressions and examinations of Mr. Svekla's small fleet of aging vehicles revealed little. The RCMP questioned Mr. Svekla and released him without charges. But they continued following him as a person of interest.

Two years later, upon release from a short stint in prison in High Level, in Northern Alberta, Thomas Svekla headed to his sister's Fort Saskatchewan home, bringing with him a hockey bag he'd retrieved from a derelict truck. He claimed it contained soil and compost worms. His sister and her husband didn't believe him. After Mr. Svekla went out, the couple investigated the contents of the bag. What they discovered led them to alert the police.

Const. Steve McQueen arrived at the house shortly after midnight on May 8, 2006. He unzipped the bag and saw a dark rubber inflatable air mattress bound tightly with wire. Donning latex gloves, he probed around and found himself concurring with Mr. Svekla's family: The bag contained human remains, later identified as those of Theresa Innes, a sex worker in High Level.

With Insp. Sekela away at a conference in Britain, Staff Sgt. Simmill made the call: The RCMP finally made its first arrest, apprehending Mr. Svekla. The police eventually laid murder charges connected to the deaths of Ms. Innes and Ms. Quinney.

Mr. Svekla claimed someone had planted Ms. Innes's body in his truck, and maintained he'd happened upon Ms. Quinney's body by chance. The case against him relied heavily on circumstantial evidence. Insp. Sekela, who'd seen other "megatrials" fail on procedural grounds, regarded it as a major test. "The trial of the accused is merely a sideshow," he says, quoting an old legal adage. "The trial of the investigation is the main event."

At its outset the prosecution produced a list of witnesses. It contained the names of nearly 300 people, everyone from Ms. Quinney's sister to Mr. Svekla's father, sisters, co-workers, and sex workers with whom he'd associated. Mr. Sekela confirms that KARE officers interviewed every one of them. Also included were 127 cops, forensic examiners and other personnel, each of whom had worked the cases. More than 100 witnesses testified, painting a complex picture of Mr. Svekla's behaviour and personality.

However, nobody could place Mr. Svekla with Ms. Quinney during her final moments. Nobody could satisfactorily explain why he led police to her remains. Ultimately, he was convicted of second-degree murder for Ms. Innes's death, but was acquitted on the charges relating to Ms. Quinney. "A lot of us thought he would be convicted on that one as well," says Mr. Simmill, ruefully, "but it wasn't so."

With a single homicide conviction, Mr. Svekla didn't meet the RCMP's definition of a serial killer. Project KARE hadn't fulfilled its mandate. And although Mr. Svekla was considered a suspect in six other murder investigations, he was never charged in any of the cases – nobody was.

DNA, and a slam-dunk

With Mr. Svekla in its crosshairs, the RCMP at first missed other patterns. Two days after the murder of Ellie May Meyer, a group of five people visited West Edmonton Mall. Joseph Laboucan, 19, was the dominant personality in the group. Stephanie Bird had previously dated him. Her new boyfriend, Michael Briscoe, was nearly twice the age of the rest of the group. Michael Williams went by the name "Pyro," an allusion to his daily habit of setting things on fire. "Buffy," 16, was his fiancée; she'd dropped out of school, and adopted a "vampire" persona.

Mr. Laboucan and Ms. Bird lured two youths, one of them 13-year-old Nina Courtepatte, from the mall with promises of a bush party. Mr. Briscoe drove to the Edmonton Springs Golf Course. There, Nina was raped by Mr. Laboucan and Mr. Williams, then murdered. The group left her on the fairway and returned to Edmonton. (The other youth was not assaulted, and survived.)

The six people present for Nina's tragic final moments weren't discreet. The very same day, Mr. Laboucan phoned a friend in Fort St. John, B.C., and told her he'd witnessed a murder. When Mr. Laboucan and the others were apprehended, they wove a tangled web of denials and mutual recriminations.

The subsequent morass of trials and appeals dragged on for years. Mr. Laboucan, Mr. Briscoe and Mr. Williams ultimately earned convictions for first-degree murder; "Buffy" had one of second-degree murder; Ms. Bird was found guilty of manslaughter.

And a family was sentenced to a lifetime of grieving. Nina's mother, Peacha Atkinson, attended the trials. "When my younger daughter, Annie, turned 13, I couldn't breathe," she said in an interview last year. "I was really protective, overprotective. I put [my children] in my own jail. I don't know if I can ever get over that." (Ms. Atkinson died in December.)

Mr. Laboucan's erratic behaviour invited the question: What else was he capable of? He'd boasted to others that he'd killed 189 people. "Buffy" testified that Mr. Laboucan regularly sought to kill random people "every two or three nights," usually on Edmonton's outskirts.

The inflated victim tally was presumably fantasy; Mr. Laboucan was, after all, barely an adult. But something else suggested that Nina Courtepatte wasn't his first victim: The morning following her murder, "Buffy" told police, Mr. Laboucan showed her a severed pinky finger he kept in a refrigerator.

Ellie May Meyer had been found missing a finger.

As a result of his conviction for Nina's murder, Mr. Laboucan had been compelled to provide a DNA sample. It matched DNA recovered from Ms. Meyer's body. Now formally linked to two homicides, Mr. Laboucan fell within KARE's mandate. This time, KARE took on Ms. Meyer's case. It proved a slam-dunk in court: In 2011 Mr. Laboucan received his second conviction for first-degree murder, and KARE finally had a bona fide serial killer behind bars.

'What have they solved?'

Yesterday's unsolved crimes have a way of resurfacing in the present. In April, 2015, a property owner near Leduc, south of Edmonton, was walking through a wooded area when he happened upon skeletal remains. They turned out to belong to Delores Brower. A police search of the surrounding area discovered the remains of Corrie Ottenbriet, who had vanished 11 years earlier. Maggie Burke is among those still missing; Crime Stoppers erected a billboard last December at 117th Avenue and 95th Street, pleading for anonymous tips about her disappearance.

Each missing or murdered woman represents a grieving family and a mystery unsolved.

Thirteen years after the project began, the results visible to the public are hardly encouraging: two murder convictions and dozens of unsolved crimes, many of which occurred under KARE investigators' noses.

"What have they solved?" asks Don Langford, of the Métis Child and Family Services Society, one of KARE's former social-agency partners. He says he's heard from families of many indigenous victims, and most are unhappy with the RCMP. "I guess that was part of the frustration of being an aboriginal person. You know, people have given, I think, some pretty decent information and whatnot. How come nothing has happened?"

Kathy King's daughter, Cara, was found murdered in a canola field east of Edmonton in 1997. Although Ms. King praises the RCMP for its professionalism in investigating the case, she, too, was disappointed by KARE's low number of arrests and convictions. (Cara King's murder remains unsolved.) "When you think of all the money and resources poured into that investigation, it really makes me wonder why there's not more evidence," she says.

Of the 49 female homicide cases for which the Globe has data, offenders were identified and convicted in just nine, two of which KARE was responsible for. (One additional case is before the courts.) Some blame KARE. Citing its sizable budget and manpower, Bill Pitt, a retired criminologist who served as an RCMP officer decades ago, says that scoring the team a C-minus would be generous. "They never got their Pickton," he says. Mr. Pitt deems Mr. Svekla and Mr. Laboucan "minor-league players," too stupid and disorganized to have orchestrated killings on the scale experienced in Edmonton.

Thirteen years after the project began, the results visible to the public are hardly encouraging: two murder convictions and dozens of unsolved crimes.

Amber Bracken for The Globe and Mail

Will time loosen tongues?

KARE has been largely discontinued. In 2009, Staff Sgt. Simmill retired and Insp. Sekela was promoted. Edmonton Police Service pulled its members from KARE in 2012, and the RCMP wound up the project.

Today, Mike Sekela is director of investigations at the Alberta Serious Incident Response Team, where he works on probes into police-involved deaths and misconduct. (Some of his current team members are former KARE alumni.) Though he's left the RCMP, Mr. Sekela remains proud and protective of KARE's legacy. He knows KARE's record in court leaves critics unimpressed. He chooses his words carefully. "As a couple of people went into custody," he says, "you'll probably notice in your research that the amount of people that ended up dying decreased quite a bit."

Indeed, the Globe's own data suggest that the number of "killing field" homicides fell sharply in the late 2000s and has remained low ever since. Other sources offered similar observations. Edmonton still has one of Canada's highest murder rates, but the profile of the victims has changed. Perhaps the offenders responsible for Edmonton's "killing field" homicides are incarcerated, for murder or for unrelated offences. Perhaps they've moved elsewhere. Perhaps they died. Perhaps they've simply stopped killing, for now or forever.

Staff Sgt. Murray Marcichiw now supervises KARE's remaining components, some of which have become permanent features within K-Division. He's responsible for K-Division's missing persons and Pro-Active teams, the latter of which continues to use the KARE brand. KARE's cases continue to be investigated by two teams within a new Historical Homicide Unit.

Mr. Marcichiw insists that more KARE cases might yet be solved. Time has a way of loosening tongues; simply reinterviewing witnesses years later can yield new information. So can resubmitting exhibits for analysis, given advances in DNA and other forensic technologies. "We may already have talked to a potential suspect, but we don't know it yet," he adds. "We might just need one piece of information to get us to the point where we can prosecute."

Seemingly cold cases sometimes spring to life. On March 23, Mr. Marcichiw's historical homicide unit joined with counterparts in Saskatchewan to announce the arrest of Gordon Alfred Rogers, 59, charged with two counts of first-degree murder. The charges relate to two indigenous female victims who went missing from Lloydminster, about 200 km east of Edmonton, in 2007 and 2009, and whose remains were found outside town. The allegations against Mr. Rogers have not been proven in court. KARE alumni were involved in both investigations, and for Mr. Simmill this represents an important part of KARE's legacy. "We made better policemen out of individuals who were part of the project," he says.

KARE endures in other ways, too. It was intended to serve as a template for future RCMP serial-homicide investigations, and it has: Project DEVOTE, a partnership between the RCMP and the Winnipeg Police Service, was moulded in its image.

But its most visible and celebrated function – the once-pioneering Pro-Active Team – conducted its last street patrols in 2014. It now focuses on other vulnerable populations: children in care, people owing drug debts, gang members. Some of KARE's former partnering social agencies are furious. Métis Child's Ms. Thomason says that many of the policing challenges KARE intended to address remain evident in Edmonton. Some Edmonton-area policing agencies still don't take missing-persons reports from indigenous families seriously, she says. And the RCMP's street intelligence grows staler by the day. "We have new girls out there who've never been registered" in the RCMP's database, says Ms. Thomason.

The war waged by KARE, in Ms. Thomason's view, is far from over. While she concedes that the number of street sex workers has decreased in recent years, she knows the street's rhythms well and doubts that the change is permanent. Kate Quinn, CEASE's executive director, says it's already reverting, amid Alberta's current economic strains. "There is an increase of women on the 95th Street and 118th Avenue corridors," she reports. "Some women who haven't been seen for years are cycling back, likely due to poverty, and the others are there due to trauma – mental health, homelessness and the drug trade, all of which increase vulnerability."

Indeed, such is the street's gravitational pull that it continues to overpower even the collected horrors of the "killing field" murders. Following one homicide – the Globe chose not to identify the specific crime, to protect the family's privacy – the victim's sister left the sex trade. But "that lifestyle can't be broken sometimes," says Ms. Thomason. "It was maybe two years after that that her sister started coming back out … We still argue with her. She knows her sister was brutally murdered." Confronted with such realities, Métis Child and Family Services considers it a success to get clients off the streets for even relatively brief periods.

KARE's triumphs are similarly ephemeral. And if Edmonton is indeed witnessing a resurgence in its street sex trade, then KARE – or something like it – could be needed again.

Matthew McClearn is a data journalist with The Globe and Mail's projects team.

MISSING AND MURDERED: SEARCHING FOR THE LOST

Watch The Trafficked: One woman’s journey from forced prostitution to human rights advocacy

4:01