Age: 39 years old

Hometown: Oromocto, N.B.

Resided: Doaktown, N.B.

Unit: 2nd Battalion, Royal Canadian Regiment, CFB Gagetown

Retired Sergeant Anderson was a child of the military. He was born in Lahr, Germany, where his father was stationed with the Canadian Forces. The family moved a lot during Peter Anderson’s 30-year army career, to Yellowknife, Gagetown, N.B., and to Cornwallis and Cape Breton in Nova Scotia. A rambunctious child who didn’t like to be stuck inside, Sgt. Anderson was in the army cadets and reserves before joining the regular force at 19. By the time he deployed to Afghanistan for the second time, the proud infantry soldier had already completed four overseas assignments, including three missions to the former Yugoslavia.

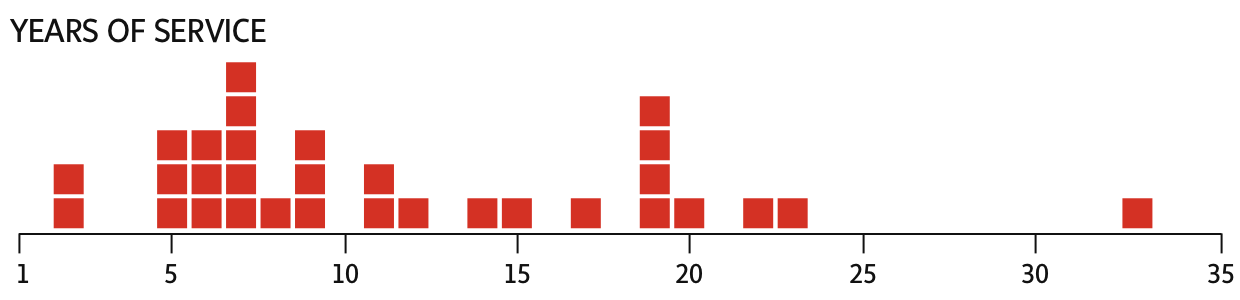

Sgt. Anderson served for two decades in the army. He completed five overseas tours, including two tours in Afghanistan.

Photo courtesy Anderson family

Sgt. Anderson served for two decades in the army. He completed five overseas tours, including two tours in Afghanistan.

Photo courtesy Anderson family

Sgt. Anderson enjoyed fishing and hunting.

Photo courtesy Anderson family

Sgt. Anderson enjoyed fishing and hunting.

Photo courtesy Anderson family

Sgt. Anderson, left, with his brother, Ryan, and their parents, Peter and Maureen. His brother was released from the military last September and is being treated for PTSD.

Photo courtesy Anderson family

Sgt. Anderson, left, with his brother, Ryan, and their parents, Peter and Maureen. His brother was released from the military last September and is being treated for PTSD.

Photo courtesy Anderson family

After Afghanistan: Sgt. Anderson was showing signs of post-traumatic stress disorder before his return to Afghanistan in 2007, his parents said. But he was determined to deploy, because his younger brother, Ryan, was on the same tour. One of the deadliest days for Canadian soldiers in Afghanistan occurred during their stint. Sgt. Anderson and his crew were behind an armoured vehicle that was struck by a roadside bomb on April 8, 2007. Six soldiers were killed – five from Gagetown and one from a Halifax-based reserve. All were his friends: Sgt. Anderson and his men had to gather their remains. “He saw a lot of death and dying, and that really bothered him,” his mother, Maureen Anderson, said. His parents could see that he was struggling upon his return from the battlefield. He was drinking harder, having trouble sleeping, and was withdrawn. He wasn’t even playing with his four young children. Sgt. Anderson was found guilty in October, 2008, of uttering threats against his then-wife and her parents, but the judge gave him a conditional discharge, noting that PTSD had completely changed his life. The mental illness had affected his work, finances, marriage and family. He had never been in trouble with the law before.

Last Post: The long-time soldier sought help for his mental illness, going to counselling and taking medication. Along with PTSD, he was diagnosed with major depressive disorder. He was released from the military in May, 2013, and moved to Doaktown, N.B., with his new partner and her son. His four children joined them in August. He quit drinking to look after them, but he was struggling financially to care for everyone. Unable to work because of his illnesses, he was reliant on his disability benefits and a pension from Veterans Affairs. Sgt. Anderson was stressed, but no one thought he was suicidal. He shot himself in a shed at his home on Feb. 24, 2014, less than a year after his medical discharge from the military. He had been in the regular force for nearly two decades.

Remembrance: The Andersons have a framed picture of their son with his four kids, taken on the first day of school in September, 2013. The retired sergeant’s left arm is wrapped around his boys; his twin girls are in front. He looks so happy, sporting a big grin for the camera. It’s their last family portrait.

THE GLOBE AND MAIL

WHERE TO GET MENTAL-HEALTH HELP

Shared memories of Captain Brad Elms

Comments may have been edited or condensed

Retired Chief Warrant Officer Don Tupper wrote:

I knew and served with Brad after I joined the military in 1983. He was an instructor for our basic training and subsequent trade qualification courses. We served on a Northern European Command Infantry Competition team and later on I was his quartermaster when he was sergeant major of India Company in the 2nd Battalion, Royal Canadian Regiment.

Brad was a super intelligent and when he was not familiar with something he would see a challenge and learn the subject inside and out until he became an authority on it. I always wanted to enter him on that show, Canada’s Smartest Person. He could solve any type of problem put in front of him.

If he was your friend, you knew you could count on him, no matter how difficult the situation. He was loyal to his family, his friends and his country.

He is dearly missed.