Read the full story

The newly commenced National Inquiry into Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls will almost certainly explore long-standing concerns from indigenous communities about the police response to such cases. Yet, discussions are often complicated by the nearly impenetrable veil of secrecy surrounding most police investigations. The general public seldom sees a full accounting of steps police take (or don't take), their triumphs, omissions and errors, and the personal costs their work entails. On closer examination, however, at least some of these details can be discerned.

MURDERED

Project KARE was an RCMP-led investigation into a series of seemingly related murders and disappearances in the Edmonton area. Since at least the late 1980s, women, many of whom were street-sex workers, had been found murdered in the forests and fields on the city's outskirts. A grossly disproportionate number of them were indigenous. Edmonton's large number of unsolved cases jumped out as The Globe and Mail built its database of missing and murdered indigenous women and girls last year. A product of the fallout from policing failures that allowed Vancouver-area serial killer Robert Pickton to murder undetected for years, Project KARE represented a concerted effort by multiple policing agencies to solve these crimes and apprehend the persons responsible.

To explore why KARE's investigators solved so few cases, The Globe compiled a database of as many Edmonton-area homicide cases as we could find since 1986 in which female victims of all ethnicities were found outdoors. (We found 49, many of which KARE investigated.) We interviewed former senior KARE investigators, and current officers from the RCMP and Edmonton Police Service. To better understand the geography of these homicides, we used the GPS co-ordinates in The Globe's database to locate several of the areas to Edmonton's east and south where human remains were found.

We visited Edmonton's courthouse twice to study the handful of KARE cases that resulted in charges and went to trial. To witness firsthand the dynamics of Edmonton's street-sex trade, we joined social worker Kari Thomason of Métis Child and Family Services on one of her late-evening patrols of high-activity areas. We also spoke to the families and friends of a handful of victims to understand the extreme social costs that accompany these crimes.

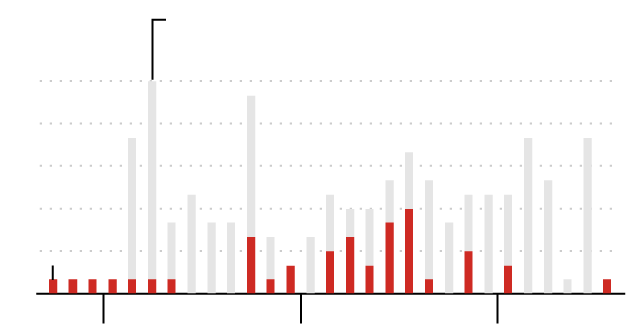

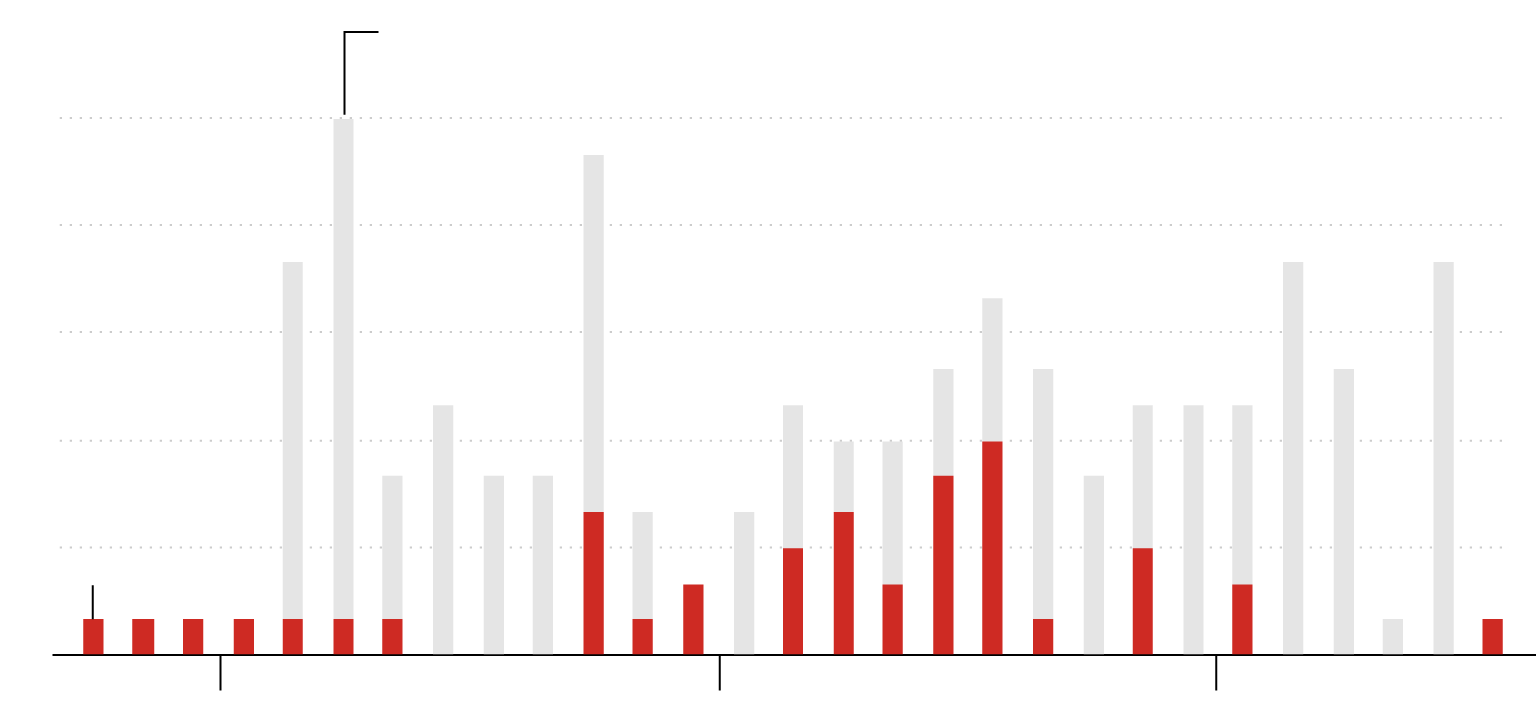

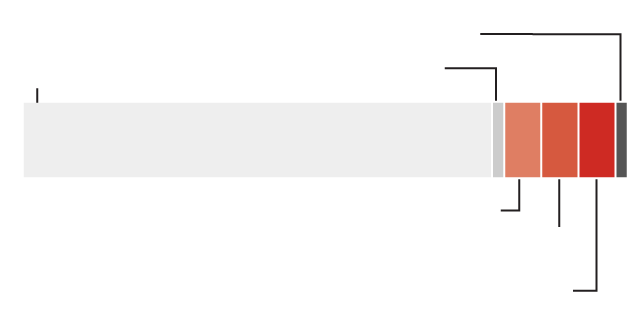

Homicide count for females in Edmonton

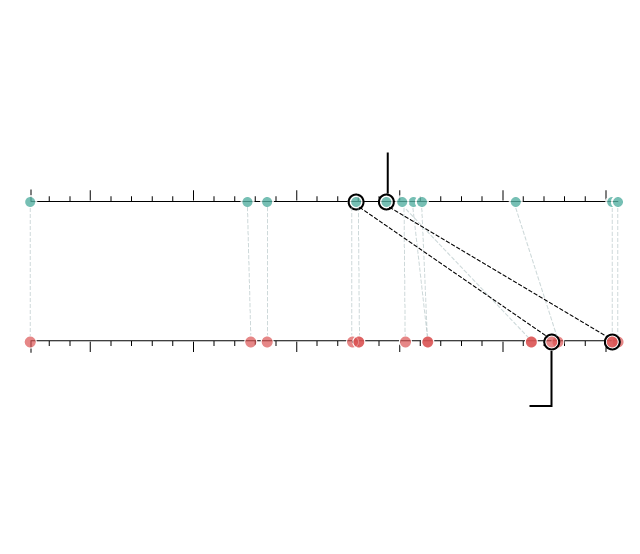

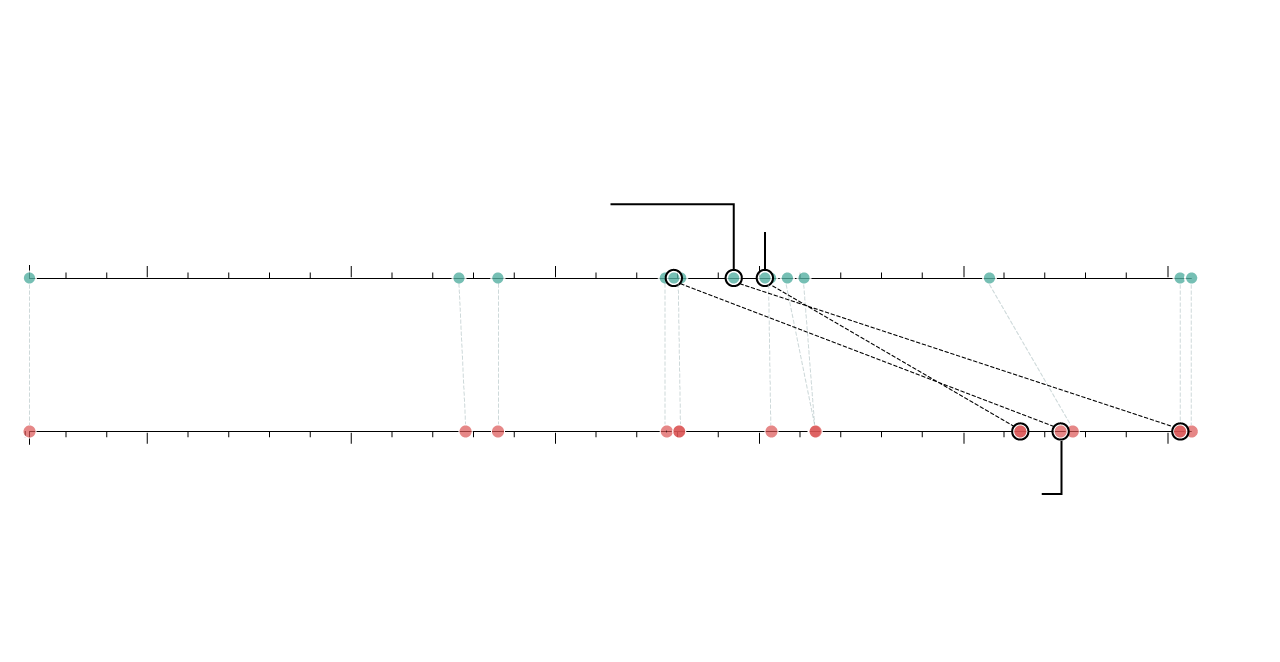

We identified 49 such cases since 1986. Our collection is in no way representative of the larger number of female homicides in Edmonton during the same period, and we may have overlooked relevant cases. Nonetheless, these 49 cases shared striking characteristics.

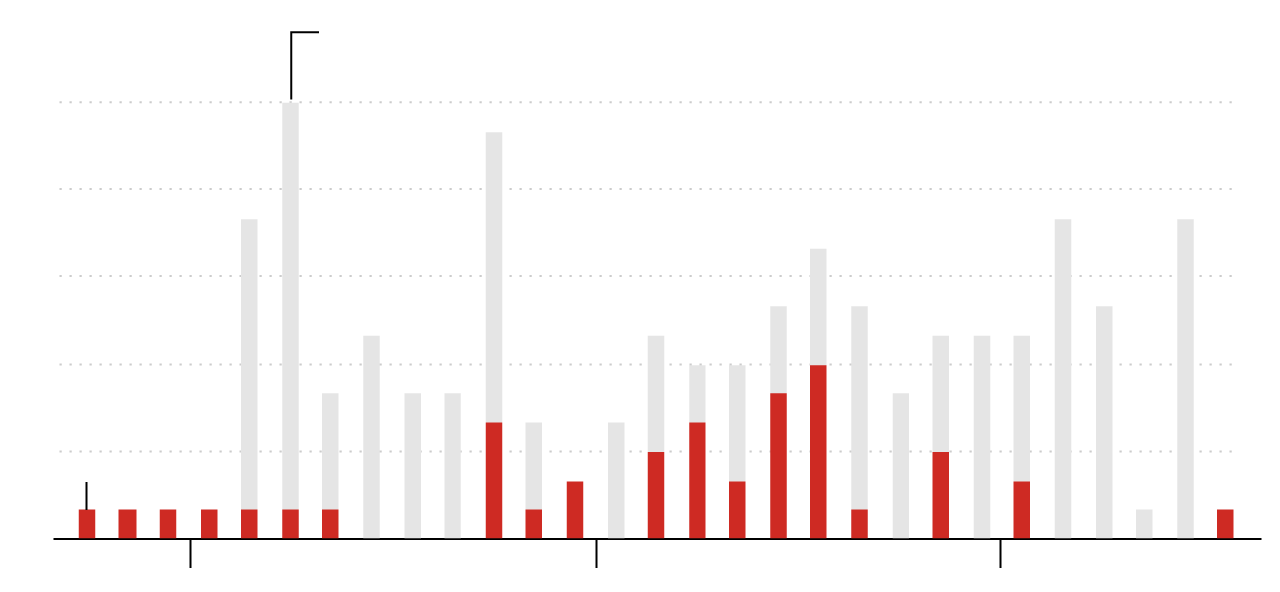

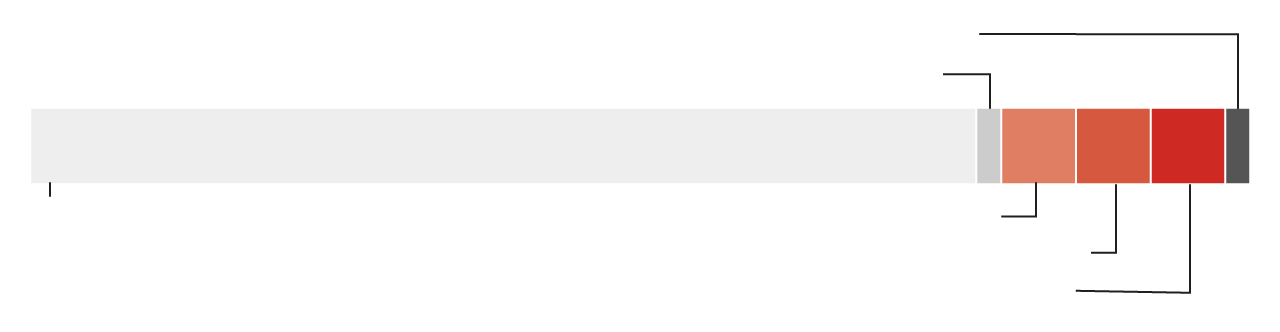

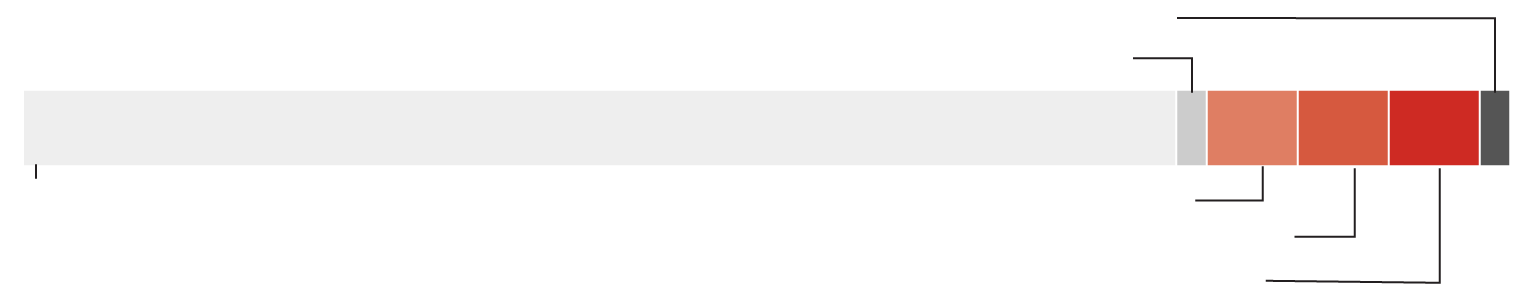

Ethnicity of the victims

Most of the homicides for which The Globe has data involved aboriginal victims. Yet, only about 5.6% of the city's female population is indigenous.

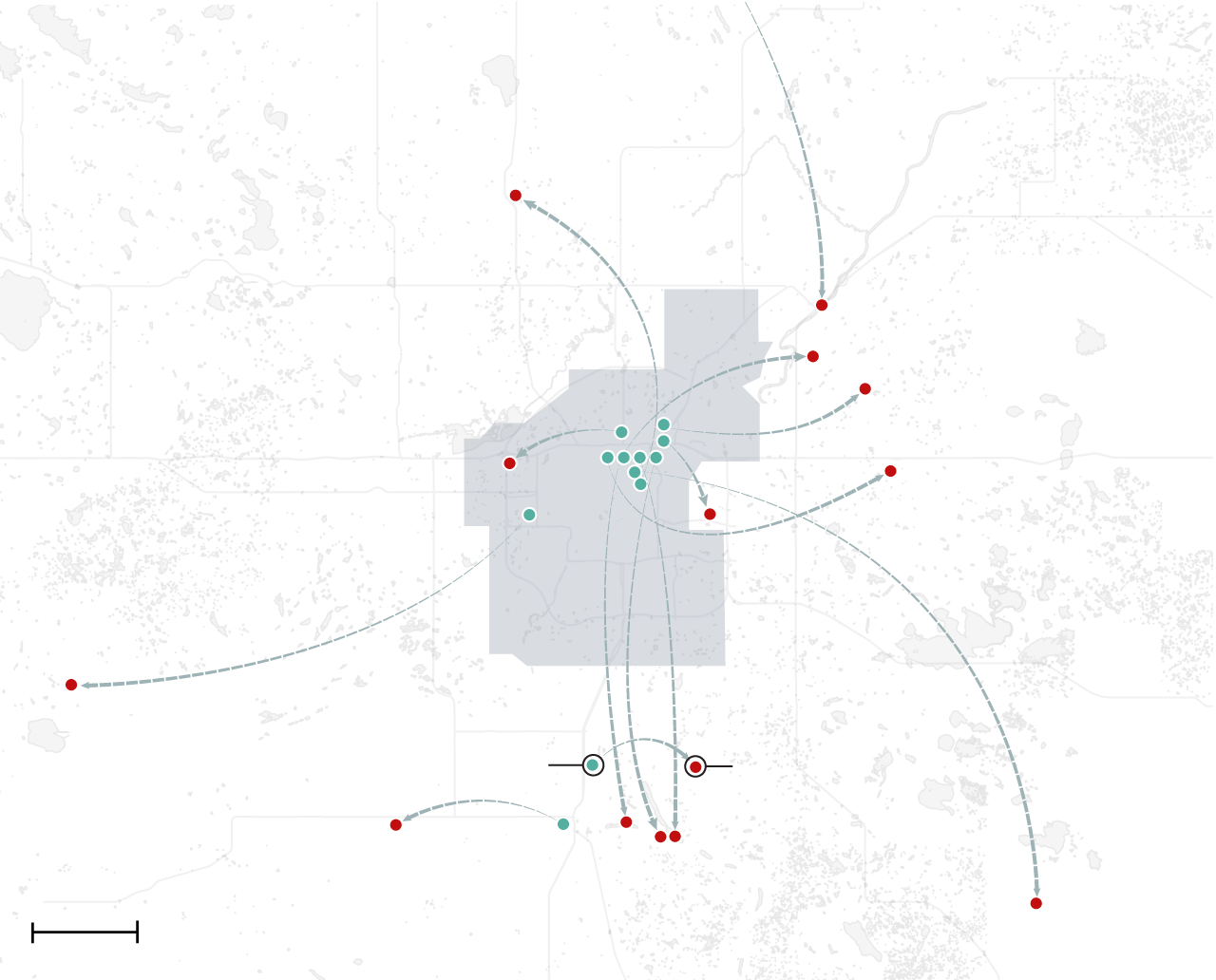

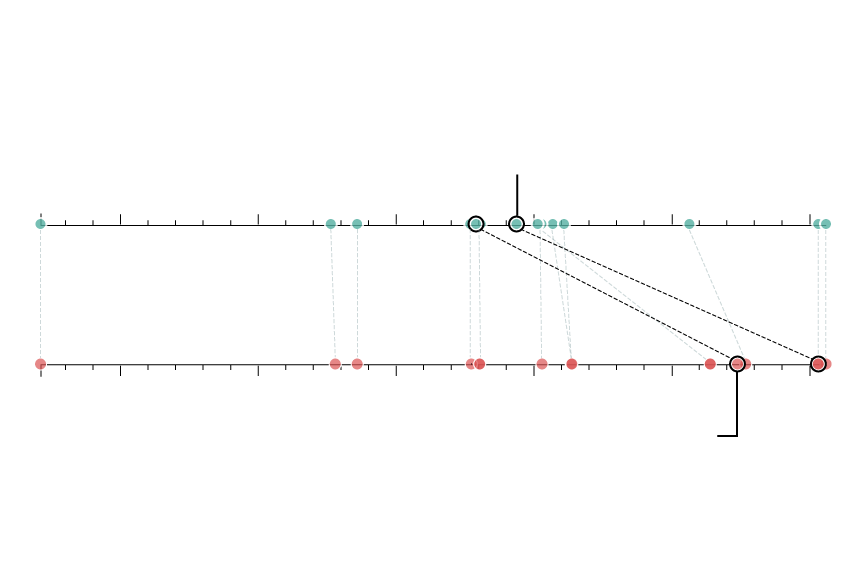

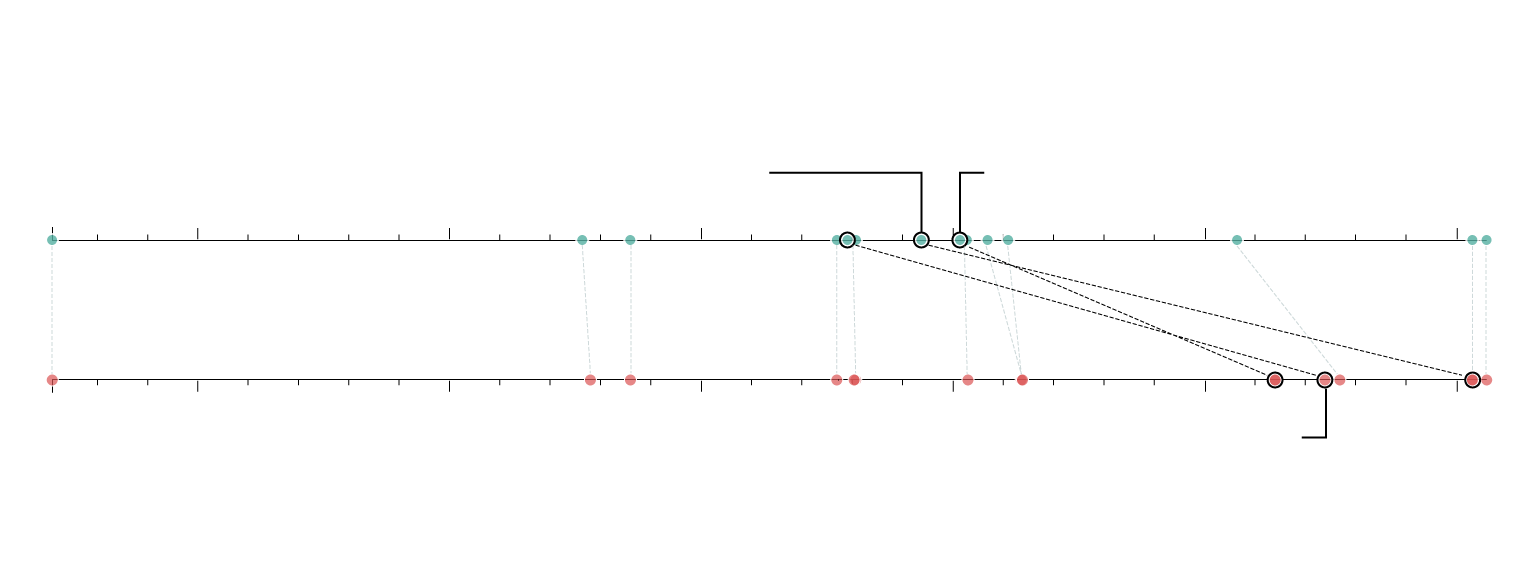

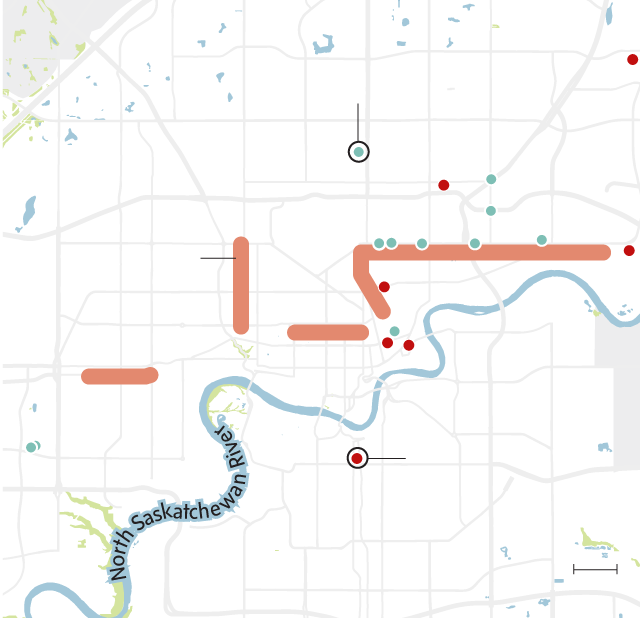

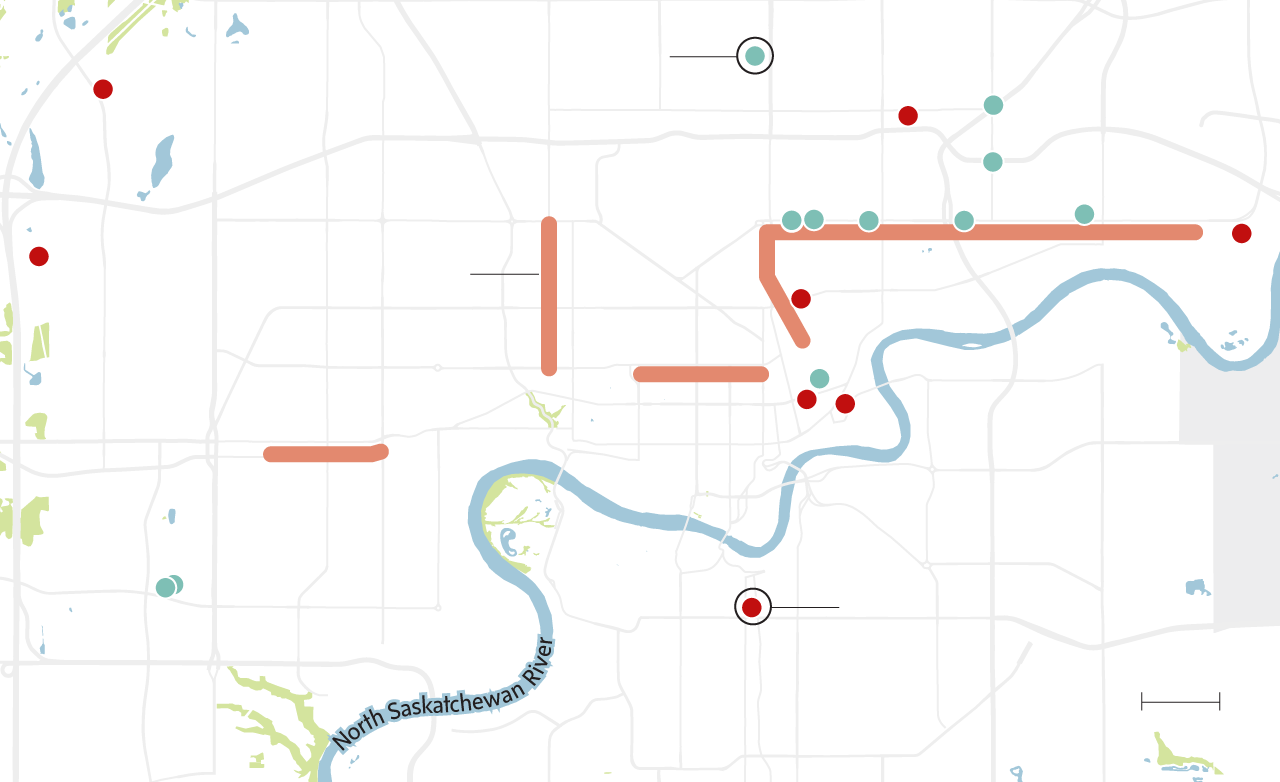

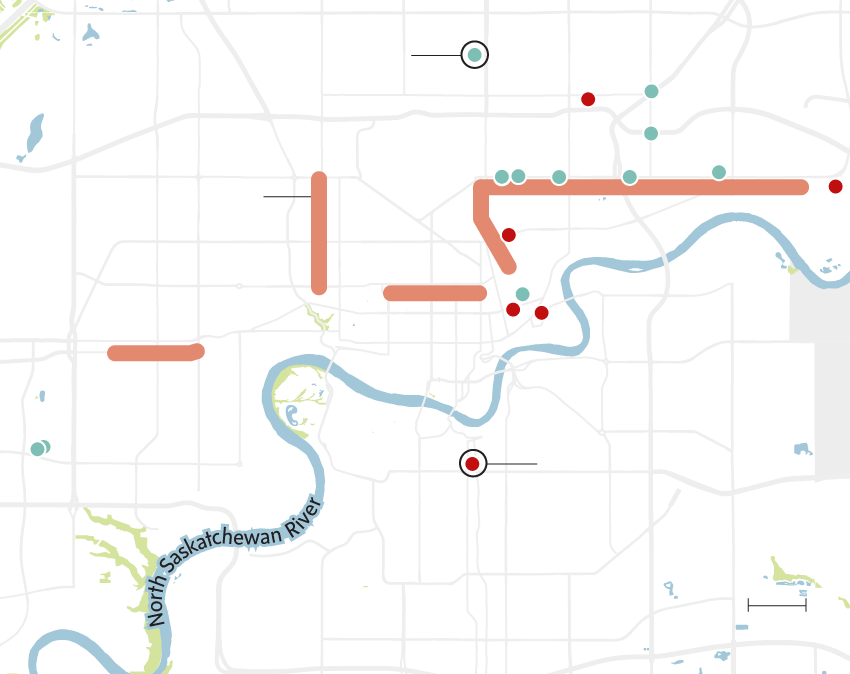

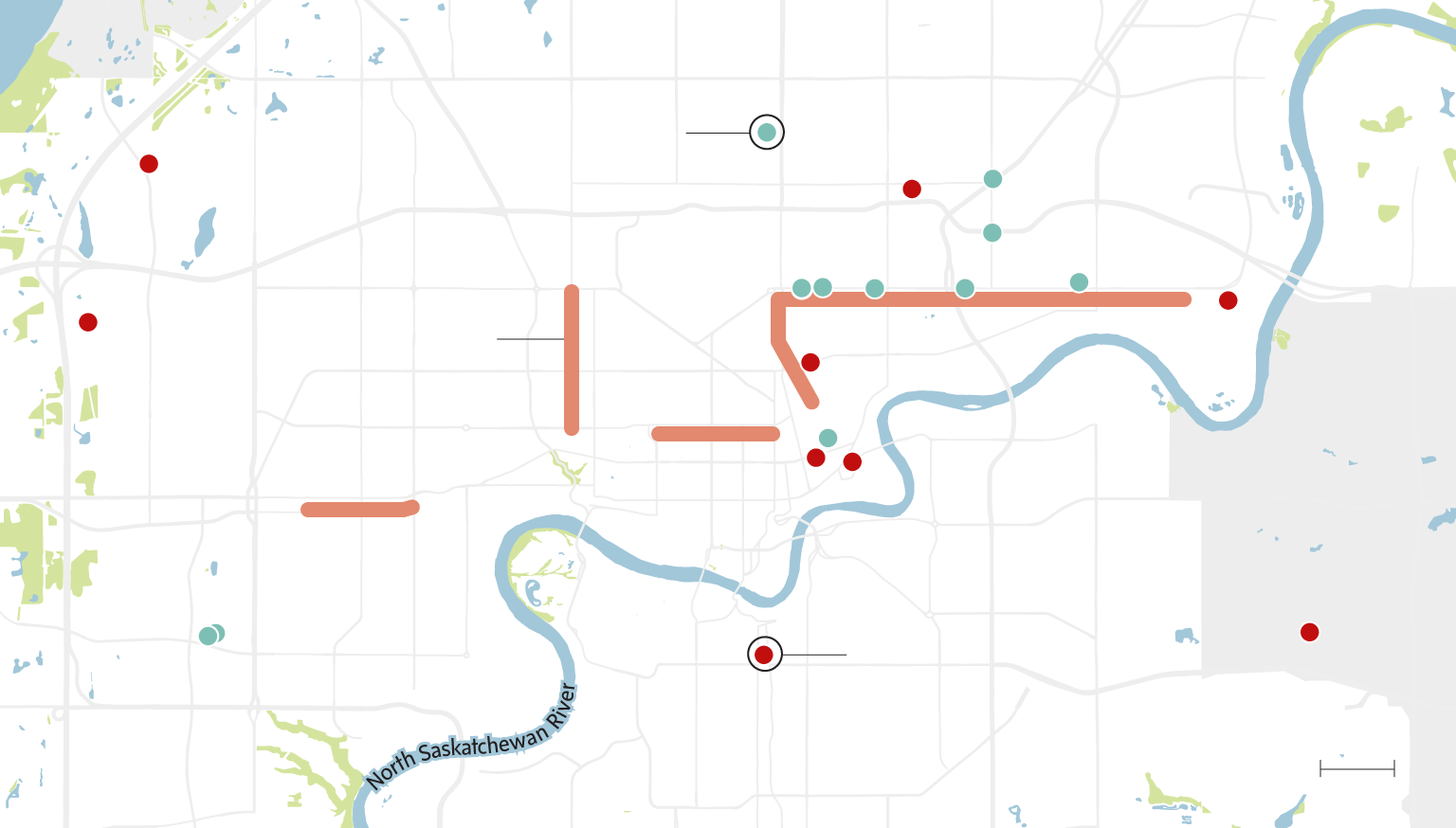

A striking pattern

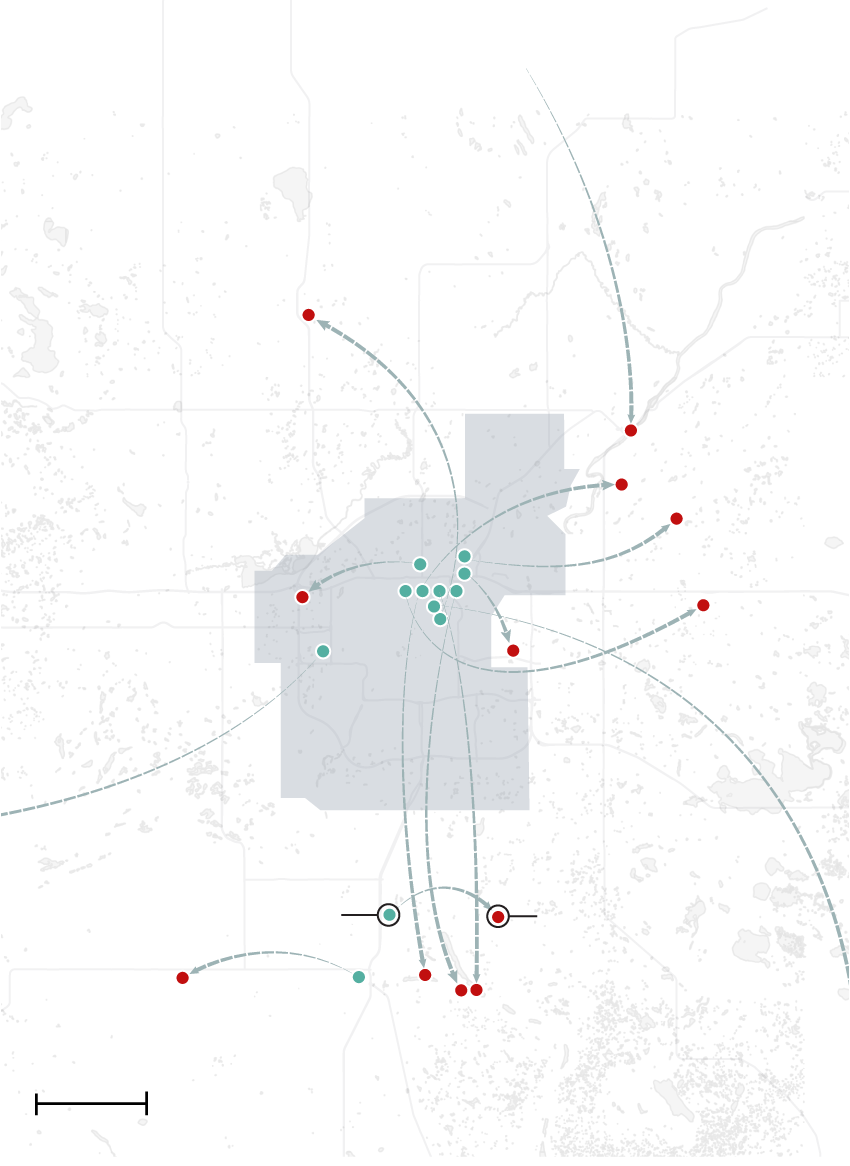

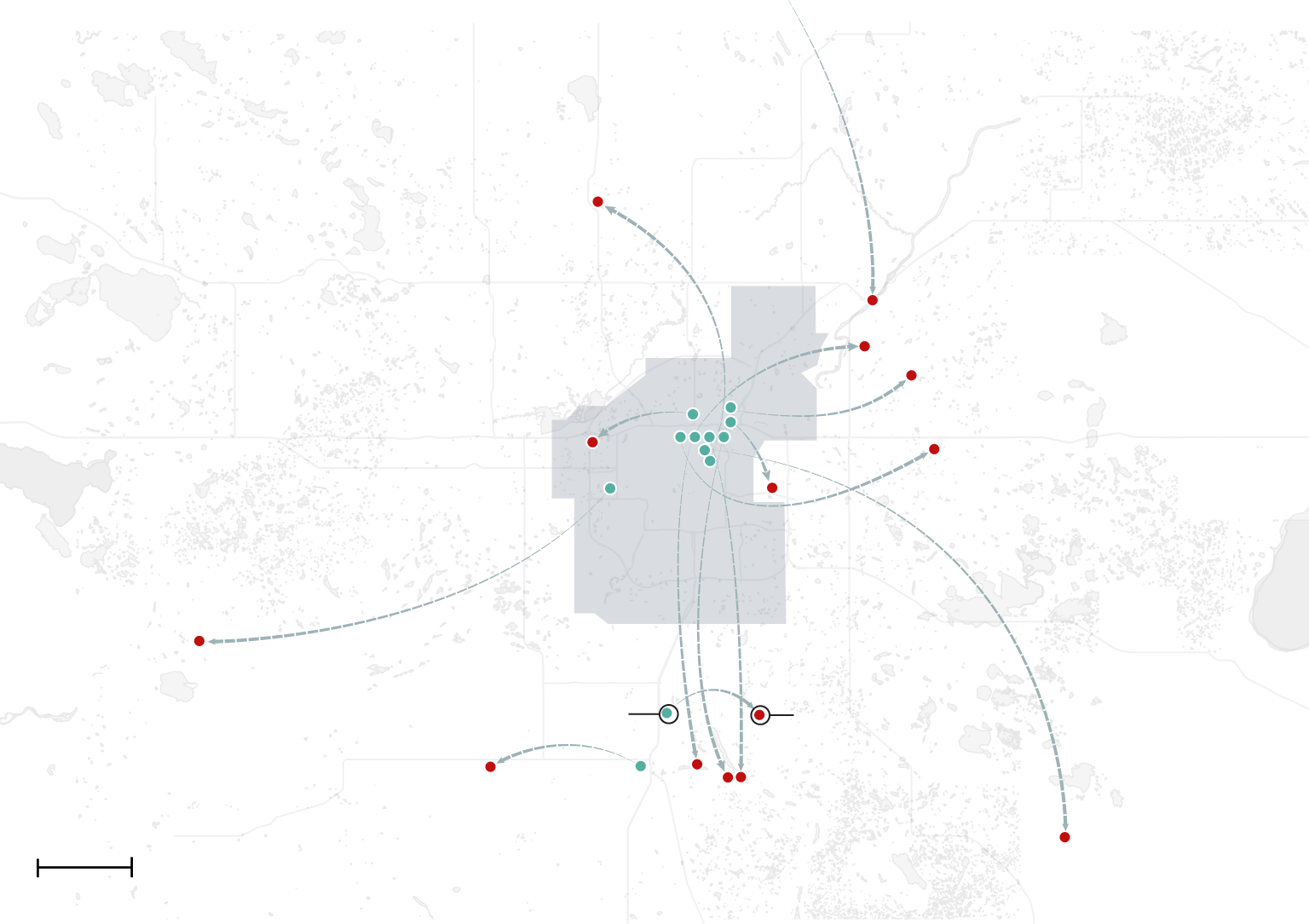

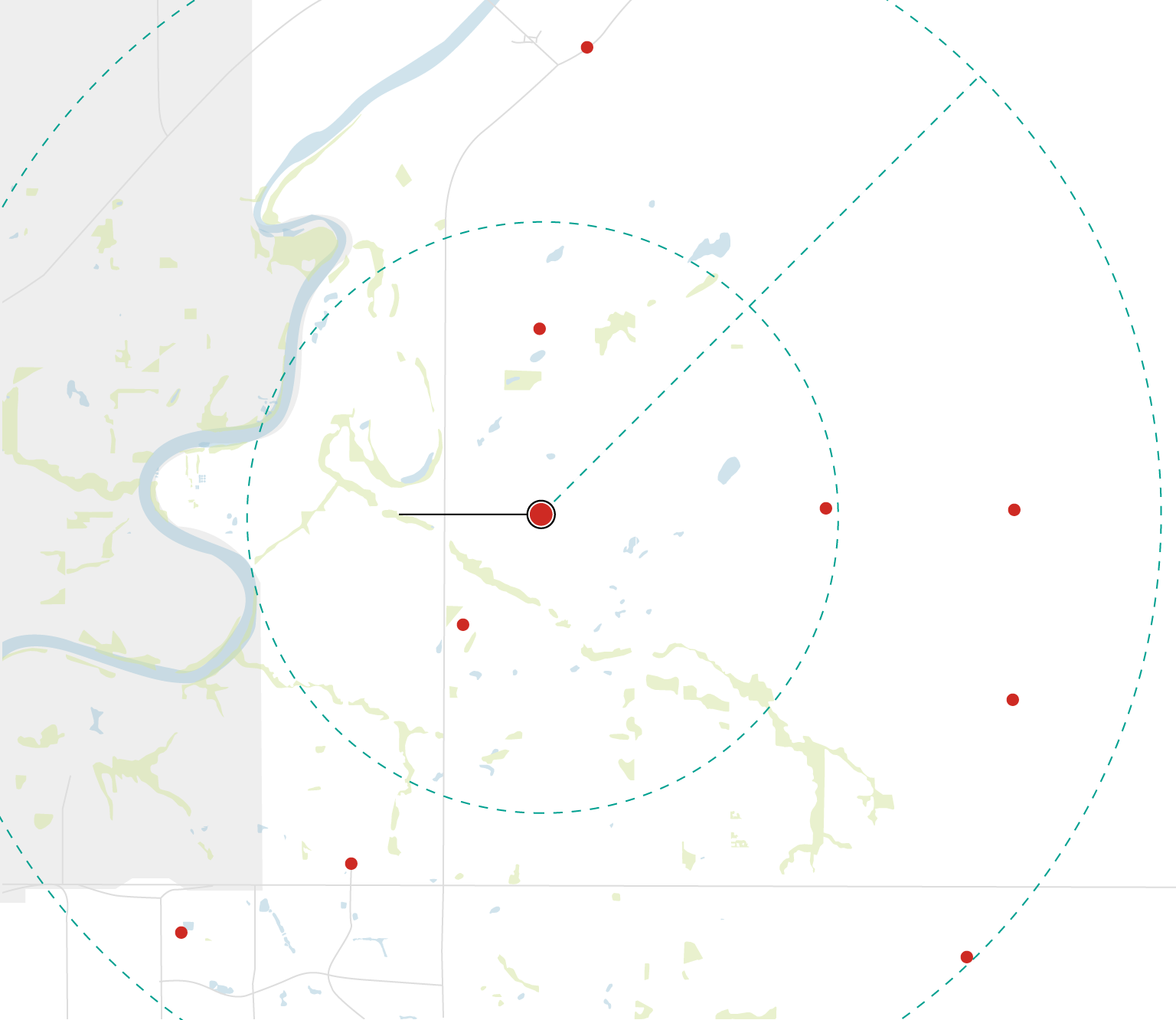

Rumours of an Edmonton serial killer began in the winter of 1987 after the remains of three women were discovered within days of each other. Project KARE was formed after another spate of killings in and around Edmonton in the late 1990s and early 2000s. By then, a striking geographical pattern had developed. This map shows cases for which we had co-ordinates locating approximately where victims were last seen, and where their remains were discovered.

Remains often lay undetected for months, even years. That greatly reduced the likelihood investigators could solve these cases, in part because memories of potential witnesses degrade quickly, as do certain types of forensic evidence. In a few instances, remains were undiscovered for many years.

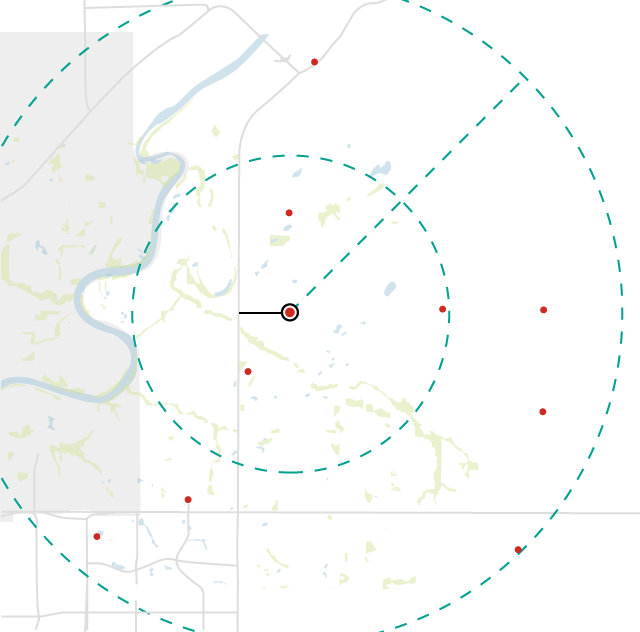

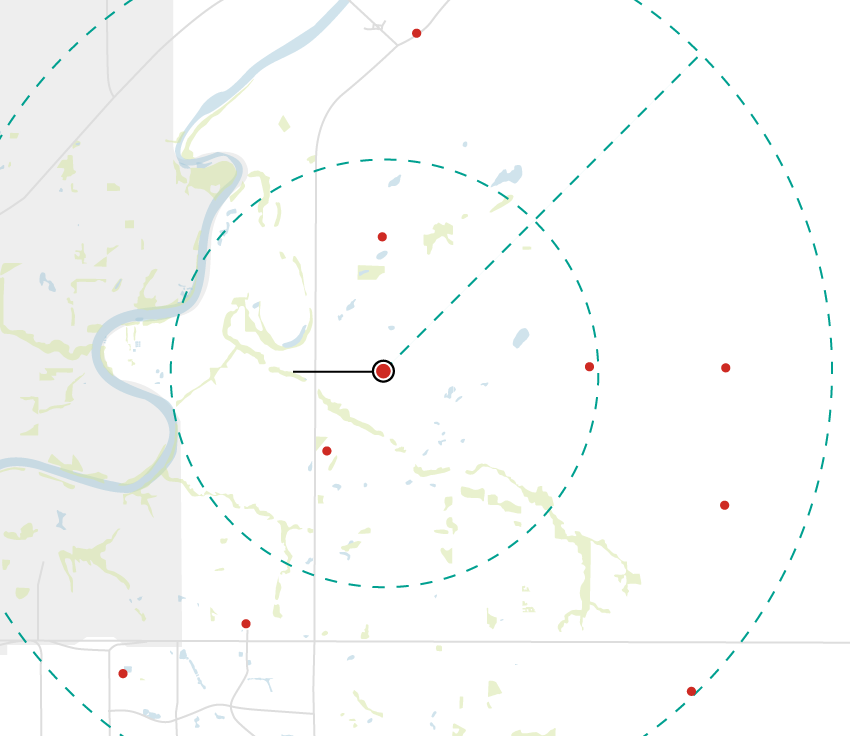

Ground zero

Many (but not all) victims were sex workers, last seen along streets and avenues where such activity is known to occur frequently. Three victims were last spotted near the intersection of 118th Avenue and 95th street, for many years the epicentre of the city's sex trade.

Street-sex work is associated with numerous hazards, ranging from frequent assaults to homelessness and lasting psychological trauma. Perhaps the most extreme manifestation of this is that sex workers figure prominently among the victims of known serial killers.

No simple task

Just because homicides coincide in space and time or bear other similarities doesn't mean they're connected. Once an area becomes notorious as a dumping ground, for instance, it may attract diverse offenders seeking to dispose of human remains.

For instance, in April, 1997, Connie Grandinetti, 38, was shot to death and dumped in a ditch south of Fort Saskatchewan, just kilometres from sites where other women's remains were discovered that same year. Yet from the outset police suspected her nephew, Cory Howard Grandinetti, for the crime. At his trial, the Crown alleged he'd killed his aunt in exchange for $10,000, fallout from a bitter family feud. In 2000 he was convicted of first-degree murder.

Many of the 49 cases the Globe examined remain unsolved, with only 11 resulting in criminal charges. That's a rate of just 22 per cent; in 2014, the RCMP indicated nearly 90 per cent of female homicides across Canada occurring between 1980 and 2012 were solved.