In the fall of 1992, a relatively unknown pharmaceutical company based in Pickering, Ont., filed a 47-page document with the Canadian Intellectual Property Office, seeking to patent a new invention it said could transform the way doctors treat pain.

Like the millions of patent applications before it, the one filed in Gatineau, Que., by the Canadian subsidiary of U.S. drug giant Purdue Pharma promised remarkable things.

The company's researchers had "surprisingly" discovered a new way to treat pain. Purdue's innovative pill would substantially improve the "efficiency and quality of pain management," because it didn't need to be taken as often as other medications.

Most importantly, it was safer. In a section of the application called "Summary of the Invention," where the benefits of the innovation are recorded, Purdue said its new pill could treat pain "without unacceptable side effects."

The drug was awarded Canadian Patent No. 2,098,738. Its official title in the paperwork was listed as: controlled release oxycodone compositions. But Purdue called it OxyContin.

It would go on to become a blockbuster drug – the most popular long-acting prescription painkiller in Canada for more than a decade, and one of the most lucrative pharmaceutical inventions to hit the market.

When asked in 2014 how much money the company had made from the drug, Purdue Canada chief executive officer Craig Landau struggled to say.

"I'm honestly not certain. I don't know. It's in the billions of dollars for sure," he told a House of Commons committee examining prescription-drug abuse.

In fact, the profits from OxyContin were massive, and growing every year. In Canada and the United States, where the drug was also patented, Purdue has made more than $30-billion (U.S.) from OxyContin since the mid-1990s.

Seeing this trend, other Canadian drug makers wanted a piece of those profits, and a series of patent wars broke out. Unwilling to wait the standard 20 years for the patent to expire in 2012, at least three pharmaceutical manufacturers went to federal court starting in 2005, seeking to produce their own versions of OxyContin.

In thousands of pages of court filings detailing those cases, which had not been made public until now, Patent 2,098,738 soon became shortened to the more manageable "Patent '738," which became short form for one of the biggest backroom battles in Canadian pharmaceutical history, though few outside the business knew it was going on.

But as the drug makers fought over OxyContin's spoils, deadly problems were emerging with the drug, and the industry knew it.

OxyContin wasn't merely a commercial success because it was effective at killing pain – it was also highly addictive. Patients who were prescribed the seemingly benign pills for everyday conditions, such as back pain, were becoming hopelessly dependent upon them, unable to break their habit and requiring stronger and stronger doses as time went on. Increasingly, people were dying.

Canada's opioid epidemic, which traces its roots back to the introduction of OxyContin and Patent '738, has now killed thousands.

Some of the biggest concerns about OxyContin, though, were raised by the drug industry itself, within numerous patent battles from 2005 to 2012 that never attracted any publicity.

Ranbaxy Pharmaceuticals Canada Inc. accused Purdue of "material misrepresentation," alleging that Purdue knew from its own clinical research that the claims listed in Patent '738, which said OxyContin was safer and more effective than other prescription painkillers, could not be supported. "Such statements were added intentionally to mislead the Patent Office into believing that an invention existed," Ranbaxy said.

Purdue disputed these allegations, and others, even as further lawsuits insisted the drug was far more addictive than its creator suggested.

But the attacks on Patent '738 weren't designed to warn the public about problems with OxyContin. Instead, their purpose was to have the courts declare the patent invalid, so that other companies could move in and manufacture their own versions of the enormously profitable pill. In doing so, they hoped to claim some of the billions of dollars being made from controlled-release oxycodone.

This is the story of how Patent '738 sparked the opioid crisis in Canada, with OxyContin serving as the gateway to an epidemic of addiction that has since spread to other, more hazardous substances such as fentanyl. It has left many dead, and many more ravaged by the drug and its implications.

It is also a tale of how marketing – not necessarily sound medicine – helped turn Patent '738 into one of the most profitable drugs the industry has seen in recent memory, and how careful Purdue has been to protect that empire, even as the damage spread.

In 2014, Purdue Canada's CEO acknowledged Canada had a problem with overprescribing opioids.

"We have a lot of work to do," Dr. Landau, an anesthesiologist and pain doctor, told the House of Commons committee.

"That said, and to state the obvious, I do represent a company and I can't remove my affiliation. We're a company, and like any other business, we need the ink on our ledger to be black and not red."

Why OxyContin flourished

When Purdue brought OxyContin to market in 1996, the company knew it needed to persuade doctors to prescribe the new pill. But it wouldn't be easy.

For centuries, chemical compounds known as opioids have been used by humans to kill pain, which stems from their ability to stimulate certain receptors in the body, just as naturally produced endorphins do.

As far back as the fourth century, the Persian poppy, known for opium, was cultivated for this reason. But it wasn't until the 1800s that researchers figured out the narcotic effects of the plant were the work of three chemical compounds – morphine, codeine and thebaine.

Morphine was first isolated in 1803, and its use as a painkiller took off in the 1850s with the invention of the hypodermic needle. But doctors were concerned about the number of patients who became dependent on the drug after taking it.

In a quest to find a less-addictive alternative, researchers in London and Germany began working on isolating other parts of the plant. British scientist C.R. Alder Wright was the first to synthesize – or chemically modify – diamorphine, in 1874, before Germany's Bayer Pharmaceutical experimented further, creating a painkiller nearly three times as potent as morphine, but thought to be far less addictive.

Bayer called the drug heroin, coined after the German word heroisch, which meant "strong and heroic." The company began marketing heroin in 1898 as a non-addictive morphine substitute, suitable as a sedative for coughs, particularly when treating tuberculosis. The initial reception was positive; the 1910 edition of the Encyclopedia Britannica described heroin as a treatment for irritable coughs, "without the narcotism following upon the administration of morphine."

But Bayer had hugely miscalculated. Heroin, it turned out, was just as habit-forming as morphine, and possibly even more addictive. The company was forced to pull it from shelves in 1913 amid complaints of hazardous use by the public, and political pressure from the government.

Convinced that a non-addictive version of heroin could be created, two scientists at the University of Frankfurt began work on synthesizing the third element of the Persian poppy – thebaine – and ended up creating oxycodone in 1916.

While morphine is a natural derivative of the Persian poppy, heroin and oxycodone are chemically modified versions of the plant's narcotic properties, assembled in a lab.

As they did with heroin, researchers underestimated the addictive capacity of oxycodone. And, like other opioids, the most dangerous side effect of oxycodone was its depressive effect on the respiratory system. Patients who took too much would simply stop breathing. With no intervention, they would die.

In Germany, chemists tried combining oxycodone with the stimulant ephedrine to combat this depressive effect, but with limited success. Oxycodone grew in use throughout the 20th century, but opioids were typically reserved for extreme pain only, and used under a doctor's supervision due to their dangers.

The century-long search for a less-addictive alternative to morphine would ultimately lead to OxyContin.

In the 1980s, Purdue Pharma developed a method to slow down the release of medicine in a pill, which it called Contin.

With Contin, Purdue figured out that by coating not only a tablet's outer layer, but also the microscopic ingredients inside, with various different waxes and resins, it could manipulate how fast the pill breaks down inside the body. In doing so, researchers could control the rate at which the active medication was released into the blood, and prolong its effect.

Tiny particles of medication, each individually coated in materials that dissolve slowly – sometimes corn proteins are used – are then pressed together into a tablet, which is covered by an outer layer of its own that breaks down more quickly.

When swallowed, the tablet starts to dissolve immediately in the stomach, releasing an initial dose of medication, while saving the rest for later. The tablet passes into the intestinal tract before further doses of medication are released and absorbed.

The result is a pill that can continue dispersing medicine eight or 10 hours after taking it, rather than the typical four-hour dosage cycle.

For years, Contin was primarily used in respiratory medication and potassium pills, but in the early eighties, a British physician treating patients dying of cancer suggested the company attempt to make a controlled-release painkiller that could replace regular morphine, which only lasted about four hours, and therefore required six doses a day for severe pain.

Purdue eventually turned to oxycodone, which it married with Contin to make OxyContin.

According to the information filed with Patent '738, the drug would slowly dissolve and, after six hours, would have dispersed only about 55 per cent to 85 per cent of the medication, depending on the patient's weight. Purdue's tests showed a substantial reduction in "daily dosages required to control pain in approximately 90 per cent of patients."

This slow release would make the drug more effective, the company said. And because Purdue claimed it lasted a full 12 hours, OxyContin would give patients less of a euphoric high up front, making it less likely to be abused and less likely to produce painful withdrawal symptoms, compared with other opioids on the market.

But there was a problem: Doctors were reluctant to prescribe it.

Purdue executives had learned through focus groups that the medical community had strong reservations about prescribing oxycodone to their patients because of the reputation opioids came with. Doctors wanted a long-lasting pain reliever that was less addictive and not subject to abuse.

"Market research done by Purdue indicated that the abuse potential of opioids was a reason physicians hesitated to write prescriptions for these drugs," Navindra Persaud, a family physician and scientist at St. Michael's Hospital in Toronto, told the House of Commons Committee in transcripts reviewed by The Globe and Mail.

The company needed to change doctors' minds about opioids. So it built its marketing strategy with that objective in mind.

"Purdue understood that the company that marketed and sold that drug would dominate the pain-management market," said John Brownlee, a U.S. lawyer who led a prosecution against Purdue in the United States in 2007.

"And that is exactly what Purdue tried to do."

How Purdue got doctors to change their minds

Purdue was new to the opioid business – but it had a lot of experience in marketing.

In 1952, brothers Arthur, Mortimer and Raymond Sackler, all psychiatrists, purchased Purdue Pharma, a small pharmaceutical company in New York then called Purdue Frederick Co., and expanded the business into a patchwork of products: earwax removers, laxatives and antiseptics.

Around the same time, Arthur, the eldest brother, joined a small advertising agency that specialized in marketing pharmaceuticals. It was there that he learned the art of changing doctors' minds.

His philosophy, developed over time, was to lavish them with free trips and dinners. He introduced pharmaceutical sales reps long before they became commonplace in the industry, and created the first medical journal advertising insert to promote a new drug.

Considered the father of modern pharmaceutical marketing, he helped boost Valium sales by persuading physicians to expand its use beyond the treatment of anxiety into conditions ranging from sleeplessness to restless-leg syndrome. Those efforts helped turn Valium into the first $100-million drug, and Arthur was inducted into the Medical Advertising Hall of Fame in 1997 for the achievement.

He was also instrumental in the development of OxyContin. In particular, his market research found that pain medicine was a significant potential growth area for Purdue.

As OxyContin was entering the market in 1996, Purdue needed to get doctors to look at opioids – and OxyContin in particular – in a new light. So the company drew upon that same marketing savvy.

There are numerous methods companies employ to market their products to doctors, including visits to their office, where Purdue coached its sales reps not to talk about the potential for OxyContin to be abused unless the doctor brought it up. It also used all-expenses-paid educational seminars, held in sunny locales, to further highlight OxyContin's safety.

Another approach known as the KOL, or Key Opinion Leader, also came in handy.

KOLs were physicians the drug company targeted to spread the word to others in the medical community. Often these doctors were the ones invited to conferences in places such as Boca Raton, Fla., and Scottsdale, Ariz., to learn more about OxyContin and its uses. Purdue played host to five of these a year, on average, pushing the notion that the new drug was safe and non-addictive.

Thomas Perry, a specialist in general internal medicine and clinical pharmacology at the University of British Columbia, remembers a half-day educational symposium he attended at Vancouver's Four Seasons Hotel in 1997. The key message was that OxyContin offered a significant new advantage in pain treatment – and was relatively safe in routine use.

The message seemed to get through.

After the presentation, Dr. Perry says he observed a "rapid uptake" of OxyContin prescriptions in British Columbia. His observations, contained in a sworn affidavit from a lawsuit against Purdue, which was obtained by The Globe, were based on patients referred to his outpatient clinic, and those admitted to hospitals.

"My impression is that both the 'continuing medical education' event I attended … and the advertising placed after 1996 in Canadian medical journals were aimed at 'softening up' the medical profession to see OxyContin as a relatively benign drug suitable for the treatment of everyday painful conditions," Dr. Perry said.

Purdue also took its message to medical schools, delivering free textbooks on pain treatment to students and supporting a week-long curriculum on pain management. But the textbooks had a problem: Purdue helped write them. Students were told OxyContin had a low risk of addiction, though the company could not support the claim with clinical data.

Instead, the free textbooks amended a World Health Organization report to add oxycodone to a list of weaker opioids, such as codeine, "thus making oxycodone appear safer than it was," the House of Commons committee heard in 2014.

The company also added words to an article about a clinical trial in the Canadian Medical Association Journal that claimed there was some evidence opioids could be used to relieve chronic pain, not just severe pain. To drive its point home, Purdue changed the document to say there was "strong and consistent evidence" of this.

"All this to persuade a new generation of doctors that oxycodone is more effective and less powerful, and therefore safer for patients and less likely to cause addiction," then-MP Terrance Young alleged in addressing Dr. Landau during the Commons committee.

An army of sales reps was also deployed. In the United States, Purdue more than tripled its sales force to promote the drug to doctors, with the total number of marketing reps jumping from 316 in 1996 to 1,067 in 2002.

Though similar numbers for Canada are not known, sales reps were heavily incentivized across the company, with Purdue dedicating millions of dollars to performance bonuses, while staff were coached to highlight that OxyContin could be used for a variety of conditions – from back pain to fibromyalgia.

Jillian Clare Kohler, a professor of pharmacy at the University of Toronto, said in a sworn affidavit from the same lawsuit against Purdue Canada that the company understated the risks associated with the drug.

"Sales representatives gave false information about the drug product to some health professionals and claimed that because it was a long-acting, 12-hour opioid, it would provide the patient with less of a 'high,' and, of equal importance, had less of an abuse potential, including withdrawal symptoms, than other pain medication currently on the market," said the affidavit, which was obtained by The Globe.

In Canada, the drug was suddenly everywhere. Dentists were soon prescribing it after wisdom-teeth operations.

The company also relied on advertisements in medical journals to reshape the image of opioids, playing down addiction concerns and suggesting OxyContin as a substitute in situations where over-the-counter painkillers such as Tylenol might have been used.

A full-page ad in the CMAJ, which is mailed to most physicians in Canada, depicted a runner climbing stairs next to the slogan: "When you know … acetaminophen will not be enough – Take the next step in pain relief."

Meanwhile, Purdue made inaccurate claims on its monograph for OxyContin, the document that is considered the definitive summary of a drug's effectiveness, including how it should be taken and what the risks are. These are written by the companies, and not always checked by regulators. They are also what doctors rely on before they prescribe.

"We actually complained to Health Canada about the OxyContin monograph and they simply wrote back and said it was not their jurisdiction to comment on the clinical accuracy of the monograph," Meldon Kahan, medical director at Toronto's Women's College Hospital, told the Commons committee.

"I found that astonishing … it suggests to me that not only did they not have the expertise, but they don't think it's their job," Dr. Kahan said. "I think it is their job – or someone's job – to say that what is in the product monograph has to be safe, true and accurate."

As physicians began prescribing OxyContin for conditions beyond severe pain, the rate of addictions soared. And because the pain of withdrawal was often worse than the condition the opioid had been prescribed to treat, some patients quickly became long-term users and built up a tolerance that required more powerful dosages. Meanwhile, provinces across the country, particularly Newfoundland and Ontario, began noticing deaths from OxyContin use.

Purdue, along with the federal Conservative government, attempted to paint the problem as one of abuse – saying people were intentionally using the pills to get high, often by crushing them to release the dose all at once. This was certainly happening, but it didn't tell the whole story.

Many of the addiction problems doctors saw involved people who were prescribed the pills legitimately. Physicians such as Dr. Kahan blame that on aggressive marketing by the company and overprescribing by doctors.

Purdue would later admit that it knew the claims it made about OxyContin's safety weren't accurate, but as the profits piled up, the company wasn't letting on.

In March, 2000, Purdue published an article in a medical journal saying that patients who took a daily dose of below 60 milligrams could stop taking OxyContin without going through withdrawal, which ranged from gut-wrenching cramps and nausea to fever, convulsions and severe headaches. Purdue would later reveal, in a U.S. court settlement, that it knew these statements were false.

In May of 2000, after millions of OxyContin tablets had been prescribed to patients, Purdue's medical-services department told their supervisors that it had received a report about a patient who was unable to stop taking 10-milligram OxyContin tablets without experiencing withdrawal.

The report indicated that such questions about patients not being able to stop "had come up quite a bit."

Similar concerns were showing up in the Adverse Reaction Reports filed with Health Canada, where drug manufacturers must report "serious and unexpected" side effects to the regulator.

Purdue began sending reports to the federal department in 2000, describing everything from patients who experienced hot and cold sweats and dizziness after taking OxyContin to fatal overdoses, according to documents obtained by The Globe through a federal Access to Information request.

A draft report dated March 20, 2003, prepared by the government's Marketed Health Products Directorate, portions of which are redacted, says there were 20 such adverse-reaction reports involving OxyContin, "and in two of these, death was listed as the outcome." However, there is no evidence anything was done.

Also of concern, the documents note that only a small proportion of suspected reactions are actually reported.

But as deaths and addictions began to mount, Purdue denied there was an issue, shifting the blame – again – to drug users purposely abusing the pills.

The scope of the problem, and Purdue's deception, did not become publicly known until May, 2007, when the company's U.S. parent and three of its top executives settled criminal and civil charges against them for misbranding OxyContin as less addictive than other narcotics. The company agreed to pay $634.5-million in fines – at the time, one of the largest settlements a pharmaceutical firm had paid for marketing misconduct.

Purdue acknowledged in an agreed statement of facts that it, "fraudulently and misleadingly marketed OxyContin as less addictive, less subject to abuse, and less likely to cause withdrawal symptoms than other pain medications."

In the aftermath, regulators, doctors and the families of victims looked for answers.

"I think the short answer is: billions of dollars in marketing. That is how the fact that opioids and other medications that are addictive was overlooked through all of this," Dr. Persaud, of St. Michael's Hospital, told the committee.

"The people marketing the medications know what they're doing when they approach regulators and they know what they're doing when they approach physicians, and they have billions of dollars behind them to change people's minds."

Dr. Kahan, in his testimony before the committee, painted a picture of how effective the OxyContin campaign was.

"Medical researchers, educators and everyone else was lecturing family doctors and saying, 'You're opiophobic if you're concerned about prescribing controlled-release opiates.'

"It was amazing how the medical profession rolled over."

How Purdue fought to keep its grip on the market

By the fall of 2008, OxyContin was bringing in hundreds of millions of dollars in profits for Purdue Canada. By the company's own admission in patent court documents, "the '738 Patent has enjoyed tremendous commercial success."

Business was booming so much that Purdue needed more space. In Ontario, then-premier Dalton McGuinty pledged $4.9-million (Canadian) toward a $32-million expansion of the company's Pickering facility. "They have experienced growth every single year, and they have never ever laid off a person," the Premier marvelled at a news conference announcing the funding.

As they watched Purdue getting rich off OxyContin, other drug companies wanted in – and they knew that Patent '738 was their ticket.

The 20-year patent was still years away from its natural expiry date, when rival pharmaceutical firms are permitted by law to start making generic versions of brand-name drugs. But several of them didn't want to wait.

Pharmascience Inc., a company based in Montreal, sought to launch its own competitor to OxyContin and argued in federal court that Purdue's patent should be declared invalid. The reason? The claims Purdue made about OxyContin in the patent documents were inaccurate and the pills "do not live up to the promises given in the specification."

The patent promoted OxyContin by pointing out the benefits of its long-lasting formula, suggesting that the amount of time doctors and nurses needed to spend on patients "is substantially reduced" because they required fewer doses each day.

But Pharmascience fired back, arguing that Purdue "had not done any clinical testing prior to Nov. 25, 1992, to justify adding these misleading references to the disclosure of the '738 Patent."

That is, the formula didn't work as well as the company claimed.

"The patent suggests that one of the advantages is that there will be better 'pain relief' but there is no evidence to support this comment," Pharmascience said.

Purdue disputed the allegations and successfully defended its patent. But the attacks from rivals – in an effort to discredit the patent and allow them into the market – did not stop.

In 2009, Purdue was again defending Patent '738 against a bid by Apotex, the Toronto-based generic-drug giant. Apotex called Purdue's claim that OxyContin reduced the number of dosages needed to kill pain, "a material misstatement made with deceptive intent."

And in 2011, Ranbaxy Pharmaceuticals of Mississauga launched its own attack, claiming Patent '738 was not legal, because it technically wasn't a new invention; it made no improvement on the drugs that came before it.

"The oxycodone controlled-release formulations of the '738 Patent do not provide any unexpected improvement in the efficiency and quality of pain management in comparison to immediate-release oxycodone formulations and to other opioid controlled-release formulations," the company said.

Purdue settled with Apotex and Ranbaxy, but the details of the agreements were not made public. Purdue told The Globe it would not comment on those settlements.

As part of both deals, though, any attempts to have Patent '738 overturned were put off until after it was set to expire. That meant the companies could not come to market with a generic version of OxyContin, at least while Purdue was still making money off the patent.

Then in 2012, with questions mounting in the United States and Canada over OxyContin's role in fuelling the growing opioid crisis, Purdue suddenly pulled the drug from the market, just a few months before the patent was to expire. It replaced OxyContin with a new version called OxyNeo.

The revamped pill was supposed to thwart abusers by making it harder to crush or chew, which could release the full dose all at once, delivering a euphoric high. Crushing the new OxyNeo pill turned it into a flat pancake. When wet, it turned to gel.

An OxyNeo brochure distributed by Purdue, and obtained by The Globe, billed it as far safer, since the new version "was more difficult to manipulate for misuse and abuse."

But the statement came with an asterisk. Listed in small print along the bottom of the brochure, Purdue said: "the clinical significance of these results has not yet been established."

Abuse wasn't the whole problem though, because OxyNeo was also addictive. And, like the succession of opioids that led researchers from heroin to oxycodone, this new innovation was again billed as less dangerous than the ones that came before it.

The expiry of Patent '783 in 2012 spawned two events that would cause the already festering opioid crisis to get worse. First, when OxyContin was pulled from the market and replaced with OxyNeo, it sent those dependent on it – both abusers and patients who became addicted –struggling for something to replace it.

Just as that was happening, six drug makers in Canada began producing generic versions, filling the void with an abundant, cheaper supply.

Purdue saw its share of the market shrink, as the industry shifted from brand name OxyContin to the readily available generics.

In 2010, Purdue sold $250-million worth of OxyContin in Canada, according to figures provided to The Globe by IMS Brogan, a company that tracks pharmaceutical sales. Purdue also claimed 20 per cent of all opioid prescriptions in Canada (a category that includes morphine, fentanyl and others, as well as OxyContin).

But by 2014, Purdue's market share dropped to 16 per cent, while the overall number of opioid prescriptions in Canada continued to climb.

In 2015, doctors wrote one opioid prescription for every two Canadians, according to the IMS Brogan data, making Canada the world's second-biggest per-capita user of opioids, behind the United States.

Purdue has tried to keep generics out of the market to preserve its monopoly, but to no avail. In documents filed this year with the federal lobbyist registry, Purdue Canada's CEO, Dr. Landau, said he spent more than 20 per cent of his time lobbying policy makers.

In the meantime, Canada's opioid crisis had metastasized into something much darker than a problem with OxyContin.

What the advent of Patent '738 did in 1992 was create a mass market for opioids – introducing patients and abusers to a new kind of product that had not been prevalent before, and getting them addicted to it.

Once OxyContin was replaced by OxyNeo, a host of stronger opioids began flowing into Canada to feed that appetite, and organized crime filled the void. Illicit fentanyl began appearing on Canadian streets in 2013, just months after Purdue began withdrawing OxyContin from the market.

Fentanyl and carfentanil – a powerful opioid used to tranquilize elephants and other large animals – slipped into Canada from China, from manufacturers who shipped it through the mail.

Suppliers in China had figured out that Canadian border guards were prevented by law from opening packages weighing less than 30 grams without the consent of the recipient. That created a loophole to ship drugs through, using innocent-looking envelopes.

With fentanyl being 100 times stronger than morphine, and carfentanil many times more powerful than fentanyl, just a trace amount of powder could be sold on the street and do considerable damage.

The illicit drug makers also understood another key thing about their market – OxyContin was where it all started, and it was still in demand, even though it was gone.

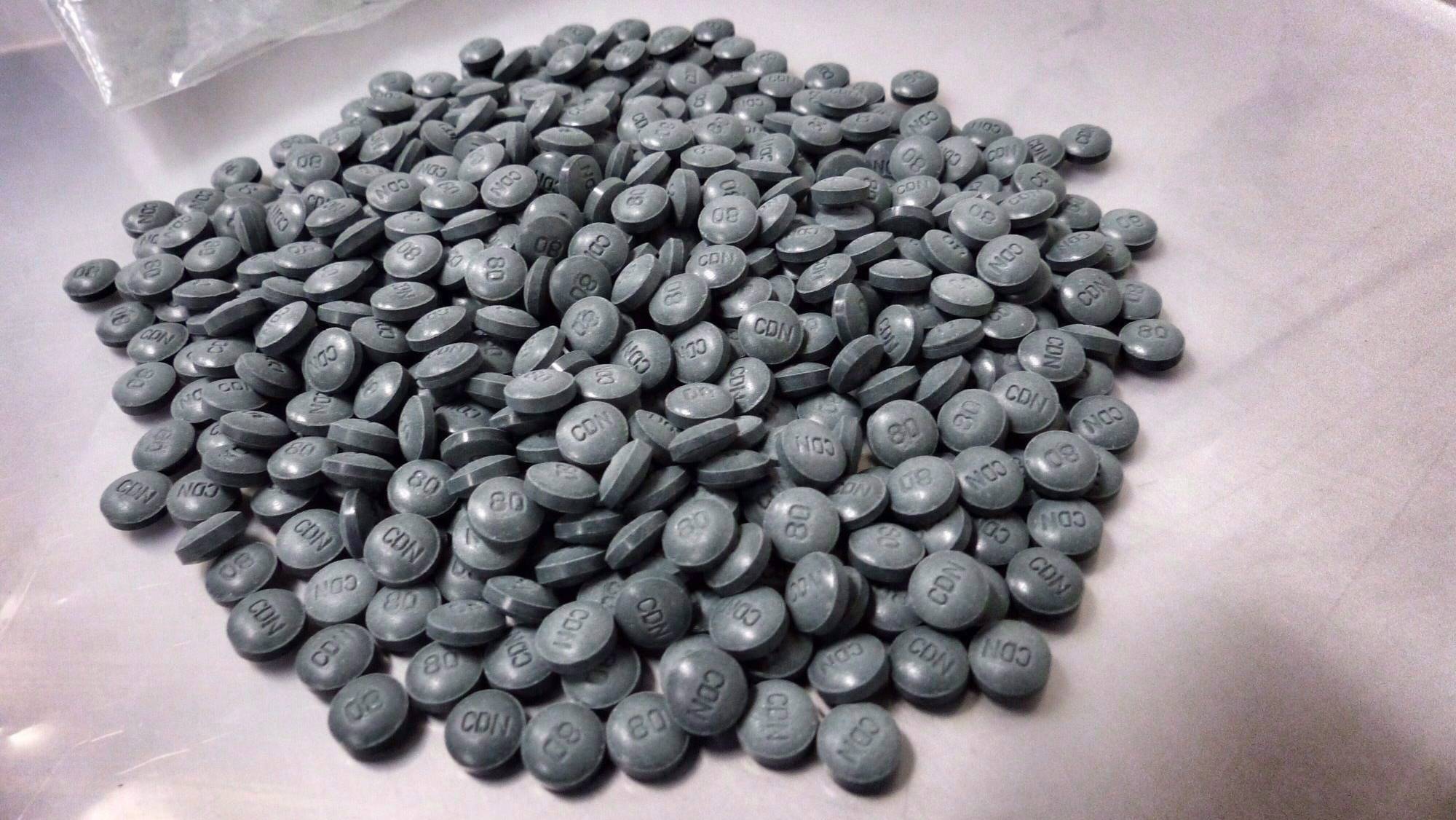

So when they turned fentanyl and other powders into tablets, using pill presses similar to those housed at big pharmaceutical factories, they dyed them green and stamped each one with a small 80. The look was designed to replicate the 80-mg OxyContin tablets that were so addictive. It was, after all, what the market wanted.

In December, the federal government, in a bid to stem the tide of illegal opioids on the street, unveiled legislation that would give border guards more power to search envelopes weighing less than 30 grams coming into the country. And the importing of pill presses into Canada was also banned.

A new courtroom battle

There has been much debate about how those involved in the opioid crisis – from the medical community to the pharmaceutical sector – characterize the problem.

Purdue has constantly referred to those who have become addicted to OxyContin as abusers.

The company believes making tablets difficult to tamper with is the solution. "While abuse-deterrent formulations are not a 'silver bullet,'" Purdue said in a statement to The Globe, "they are one important and available tool that can help to deter misuse, abuse and diversion of these medicines."

But the doctors who first began to raise alarms over the aggressive marketing of opioids say the root of the problem is in the overprescribing of an addictive drug whose risks are substantial, and benefits uncertain.

Dr. Kahan has his own word for what has happened: iatrogenesis.

Drawing from the ancient Greek word for physician – iatros – the term is used to describe a health problem that is caused by a medical procedure.

He sees the opioid crisis as just that.

"We are experiencing a unique iatrogenic – or physician-caused – public-health crisis. In Ontario, there are 500 deaths per year from overdose. No other prescribed medication comes close to the suffering caused by opioids," Dr. Kahan told the committee hearing.

"Most of the people whose lives have been destroyed by opioids were not seeking out opioids to get high. In fact, they were first exposed to opioids through a legitimate prescription for chronic pain."

"It's impossible to become addicted without exposure." Dr. Kahan said.

Though Purdue claims to have confronted the problem by introducing OxyNeo, some doctors are not convinced.

"The bigger issue is there are simply too many people on opioids," said David Juurlink, head of clinical pharmacology and toxicology at the University of Toronto. "This is about medical practice, not about the formulation."

Abuse-deterrent opioids in general are a "good thing," Dr. Juurlink said, "But it's foolish to suggest that this is the way out of the North American opioid problem."

At the height of OxyContin sales, drug companies in Canada waged a war over Patent '738 and the billions of dollars that kept Purdue's ledger awash in black ink. Now, a new legal battle is brewing.

Halifax lawyer Ray Wagner, along with two Toronto law firms, has launched a class-action lawsuit against Purdue, representing 1,600 Canadians, many of whom inadvertently became addicted to OxyContin after their doctors prescribed it. These problems can't simply be written off as abuse, he argues.

"The concern we have been dealing with all along is not the abuse of the drug, but rather the addiction that's associated with it," Mr. Wagner said. "I don't see how OxyNeo addresses those addiction issues."

With Purdue, he said, "you will never hear the word addiction. You will always hear the word abuse."

MORE FROM THE GLOBE AND MAIL

On the ground with Downtown Eastside firefighters battling opioid overdoses

A look at Suboxone, a new opioid addiction treatment in Ontario