Betty-Lou Kristy of Georgetown, Ont., who lost her son Pete to an overdose of prescription painkillers, has made a “healing wall” in her basement where her son used to sleep.

MICHELLE SIU FOR THE GLOBE AND MAIL

As painkiller prescriptions and overdose deaths have risen in recent years, so too has spending on drug-addiction treatments – and provincial health-care systems are picking up the tab. Karen Howlett investigates

With research by Matthew McClearn

Spending on drugs to treat patients suffering from addiction to painkillers soared 60 per cent over a four-year period in Canada, revealing the toll an epidemic of opioid abuse is taking on the health-care system.

Public drug programs spent $93-million on medications used for addiction to prescription painkillers and illicit opioids in 2014, compared with $57.3-million in 2011, according to figures for every province except Quebec compiled by the Canadian Institute for Health Information (CIHI) for The Globe and Mail. In four provinces, this class of opioids ranked among the top 10 in spending on all prescription drugs – a group that traditionally includes medications for arthritis, high blood pressure and high cholesterol.

The figures shed new light on a mounting problem with addiction to opioids, one that medical experts say was created by the pharmaceutical industry and the health-care system. Doctors began prescribing opioids two decades ago to relieve moderate-to-severe pain as pharmaceutical firms promoted their benefits. The spending on treatment underscores the challenge policy-makers face in dealing with the fallout from the overprescribing of a drug whose risks are substantial and benefits uncertain.

A recent Globe investigation found that Ottawa and the provinces have failed to take adequate steps to stop doctors from indiscriminately prescribing highly addictive opioids to treat chronic pain. In 2015, doctors wrote 53 opioid prescriptions for every 100 people in Canada, according to figures compiled for The Globe by IMS Brogan, which tracks pharmaceutical sales.

The spending is expected to continue mounting as more doctors prescribe Suboxone, a safer but more expensive therapy than the traditional methadone treatment, and as much of the country confronts a growing number of drug-overdose deaths, owing largely to illicit fentanyl flooding the black market.

"You need a drug to get people off another drug that was prescribed by doctors," said Meldon Kahan, medical director of the Substance Use Service at Women's College Hospital in Toronto. "That's one of the sad things about this epidemic."

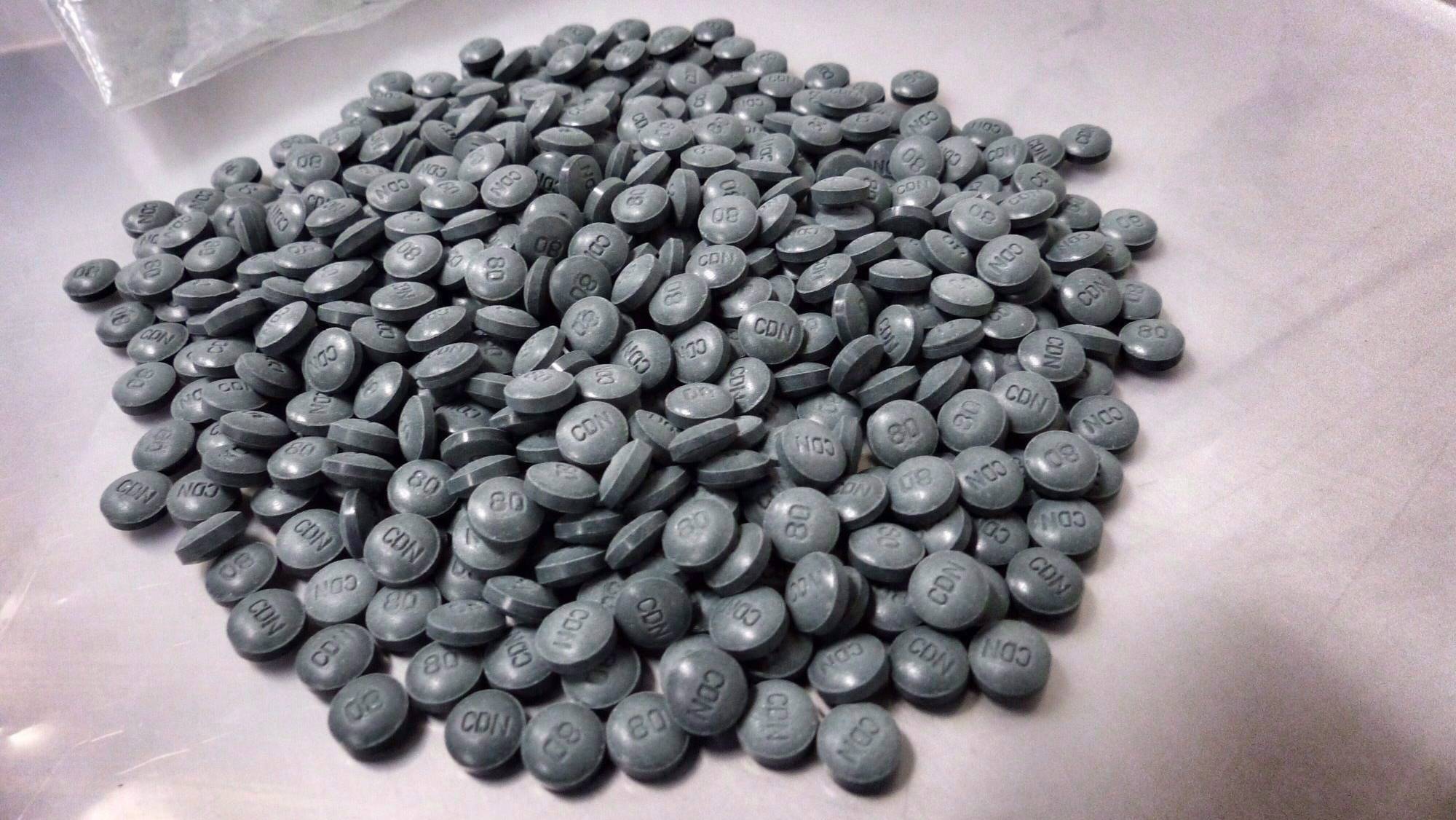

The illicit version of prescription fentanyl is manufactured in China and smuggled into Canada, where the powder is cut with other drugs and sold on the street as heroin or as fake OxyContin. In British Columbia and Alberta, the two hardest-hit provinces, fatal overdoses linked to fentanyl soared to 418 in 2015 from 42 in 2012. The scourge of fentanyl has rapidly moved east, showing up in more than a dozen communities in Ontario.

By the numbers: Three key takeaways

1 The United States is the world's largest consumer of prescription painkillers, but per capita usage is beginning to decline. By comparison, consumption is relatively unchanged in Canada, the second-largest per capita consumer of prescription painkillers.

2 As doctors in Canada continue to liberally prescribe opioids to relieve moderate to severe pain, more patients are being treated for addiction to the drugs.

3 As opioid overdose deaths mount across Canada, disparities remain among the provinces in access to treatment for people suffering from addiction.

The provinces are spending more to address the harm related to opioids as they brace for cuts to federal health transfer payments. Public drug programs in the nine provinces spent just less than $300-million in 2014 on both prescriptions for opioids and addiction medications, already consuming nearly $1 of every $5 in new health-care transfers that year.

The health accord, which guarantees a 6-per-cent annual increase in federal transfers to the provinces, expires in fiscal 2017. Payments are planned to rise at the rate of Canada's economic growth plus inflation, with a guaranteed floor of only 3 per cent.

Provincial drug programs typically pay for medications for those aged 65 and older as well as those on social and disability assistance. Just more than 40 per cent of prescription drugs are financed by the public sector, with the remainder paid for by private insurance plans and individuals paying out of pocket.

Growth in spending on drugs to treat addiction outpaced what the provinces spent on opioid prescriptions, the CIHI figures show.

"The reason the amount of these medications being prescribed is going up is because the size of the problem of opioid dependence has gone up quite substantially," said David Marsh, deputy dean and professor of clinical sciences at the Northern Ontario School of Medicine.

Dr. Marsh sees the problem first-hand in his role as chief medical director of the Ontario Addiction Treatment Centres, a chain of 57 clinics throughout the province plus one in Winnipeg. The clinics treat 10,000 patients a day – a third of everyone in the province on drugs for opioid addiction.

About 45 per cent of the clinics' patients remain in care for more than a year, Dr. Marsh said, long enough to sustain the benefits. "If they leave within a year," he said, "the vast majority will relapse."

Demand for treatment will continue to grow unless doctors stop liberally prescribing opioids, medical experts say. In June, British Columbia's physician regulatory college unveiled the first mandatory standards in Canada aimed at changing these practices. The standards, modelled on new national guidelines in the United States, require doctors to first try non-drug approaches to treat chronic pain, and to prescribe opioids sparingly by starting patients with low doses and providing only a few days' supply.

Treating patients for addiction is more expensive than prescribing painkillers to them. To better monitor patients in treatment, the medications are often doled out in smaller doses at more frequent intervals, which drives up pharmacy dispensing fees. Many opioids listed on provincial drug formularies, by comparison, are less expensive, generic versions of brand-name drugs.

The provinces spent an average of $1,554 on drugs (including dispensing fees) for each patient in treatment in 2014 – 10 times what they spent on prescription painkillers for each patient, the CIHI figures show.

The figures reveal disparities among the provinces in providing people addicted to opioids with access to treatment. In Alberta, described as an "outlier" by Edmonton-based public health and addiction-medicine specialist Hakique Virani, the province's public drug program spent just more than $1-million on addiction medications in 2014, accounting for 6 per cent of the $18.1-million spent on prescription opioids.

Government officials in Alberta have been slow to address the gravity of the opioid problem, Dr. Virani said. "Deaths are a decent indicator of the overall burden of opioid problems in our population. You would think that there would be a proportional amount of effort used to treat people who have that problem."

In Atlantic Canada, by contrast, Newfoundland and Labrador, New Brunswick and Prince Edward Island each spent more on drugs to treat addiction than they did on opioid prescriptions in 2014, the CIHI figures show. The ratio was 3 to 1 in PEI.

"This speaks to the intense effort required to treat opioid addiction," said a spokeswoman at PEI's Department of Health and Wellness.

Betty-Lou Kristy of Georgetown, Ont., wishes such efforts had been made when her late son, Pete, was suffering from addiction to prescription painkillers as well as depression and anxiety. He never had the option of getting treatment to help him with the cravings for more drugs and the withdrawal.

Betty-Lou Kristy has a tattoo of her son Pete on her leg.

MICHELLE SIU FOR THE GLOBE AND MAIL

Pete was prescribed opioids to treat his irritable bowel syndrome. On many occasions, he was rushed to the hospital crippled in pain after running out of painkillers, Ms. Kristy said. She had no idea that her son was so sick because he was going through withdrawal. Doctors responded to her son's pain by prescribing more opioids.

"Every time he went to the hospital," she said, "he would end up with more pills. The cycle continued and continued and continued."

Pete died in December, 2001, from an accidental overdose of the prescription painkiller OxyContin and psychiatric medications. He was 25.

Ms. Kristy has channelled her grief over the loss of her only child into becoming an advocate for mental-health and addiction issues. She has overcome her own addiction to alcohol and drugs and been in recovery for nearly two decades. On the 10th anniversary of Pete's death, she embarked on what became an 18-month project: getting both of her legs covered in tattoos memorializing her son.

"That's how I stayed from relapsing myself," she said.

MORE FROM THE GLOBE AND MAIL

Life lost: One mother’s tragic slide into fentanyl addiction

4:11