This article is part of The Unremembered, a Globe and Mail investigation into soldiers and veterans who died by suicide after deployment during the Afghanistan mission.

It was a drive I had done countless times since being posted to CFB Petawawa – a five-hour journey to Toronto to visit friends and family and then back to the military base. This time, though, I wasn't going back.

My four-door Honda Accord was packed to the brim with my belongings and what was left of my army kit. Just a few minutes earlier, I had been given a private farewell by my platoon, a handshake from my sergeant and a simple framed certificate by my rifle company. Then I walked out the back door of the battalion, got in my car, and, for the first time in three years, was a civilian again.

I had fantasized about this day, but as I drove away, I felt worse and worse. The front gates of the sprawling army base northwest of Ottawa had barely faded in my rear-view mirror when the lump in my throat became unbearable. I broke down and cried. I was giving up so much more than a job. I felt terrible about leaving my comrades and brothers behind. I worried deeply about the fate of so many I had served with in Afghanistan and here at home. How will they survive without me? How will I survive without them?

Just four months earlier, I had signed a contract to spend another three years in the Canadian Forces. The military first piqued my interest when I was 6 and watched my oldest brother performing drill exercises with his cadet unit in Markham, Ont. After struggling in high school and barely graduating, I reluctantly attended postsecondary. Eventually, I ended up in the journalism program at Humber College only to drop out in the third semester. Something was missing.

I was 25 when I enlisted, starting basic training in Saint-Jean-sur-Richelieu, Que., in March, 2009. A little more than a year later, I headed to the war in Afghanistan. I was filled with fear when I received the phone call informing me that I was selected to replace a wounded soldier from my battalion. I would be joining a rifle company I had never worked with before. These men and women had already forged tight bonds through months of combat.

I knew I would have to prove my capabilities immediately, so that they could trust me with their lives. Doubts overwhelmed me as I prepared to deploy, and I prayed that I would do the right thing when the time came. I was expecting the typical "new guy" welcome of cold shoulders and silent treatment. But almost immediately after touching down in Kandahar, I was welcomed with open arms and taken under the wings of strangers. Strangers who would become some of the closest friends I would ever have.

Mr. Kennedy (centre) at patrol base Sperwan Ghar in Kandahar, Afghanistan, in September, 2010. He is with members of Charles Company, 1st Battalion, Royal Canadian Regiment.

Photo courtesy Jonathan Kennedy

After Afghanistan, I was looking forward to my future as a soldier. But something changed not long after returning. I started to grow angry and depressed. I became increasingly frustrated and my morale faded. Binge drinking on the weekends brought me in contact with the law. The difficulties of transitioning from war to peace took their toll.

I had planned to be a lifer, but I began thinking about leaving the military. Indecision kept me up at nights. My initial military contract was for three years. When a second contract was put in front of me, in early 2012, I signed it apprehensively. At that moment, I could not imagine life without the military or my comrades.

Two months later, I applied for a release because I feared my physical and mental setbacks would prevent me from being a good soldier. I was scared about leaving the army, but also excited. After three years in the infantry, I thought the rest of my life would be a cakewalk. Military life had provided me with new-found wisdom. I pledged that I would never again take our freedoms and peace for granted after my time in Afghanistan.

But within a few months of release, I felt completely lost, afraid and alone. I was unemployed and in debt. I felt ashamed because I had left the only place where I ever belonged for selfish reasons. I had betrayed my friends, my unit and my country to pursue some sort of personal happiness that didn't exist.

Slowly, I began to isolate myself and felt disconnected. I had no one I could confide in. No one around me had been to war. The hypervigilance needed to survive combat lingered and crippled my days. Trips to the grocery store were filled with adrenalin and I would often leave full of rage. I reached the conclusion that I was just weak.

I had to swallow my pride and seek assistance from Veterans Affairs to pay my rent. Filled with extreme guilt for surviving unscathed, being out of uniform and on government assistance, I had lost all faith in myself. I felt that I had made a grave mistake leaving the military. The only solution I could come to was going back. I almost did.

It has been four years since I drove away from my life in the military. Not a day goes by that I don't think about Afghanistan or the people I had the honour of serving with. I didn't know anyone who died on the mission. But the list of those I know who died by suicide since returning home continues to grow.

There are not many soldiers who haven't had issues since returning from the war. There is a certain uncomfortableness we share with continuing on with our lives. We all struggle to be at peace in peace.

For me, it is still a daily challenge to move on. I was diagnosed with post-traumatic stress four months after leaving the Forces.

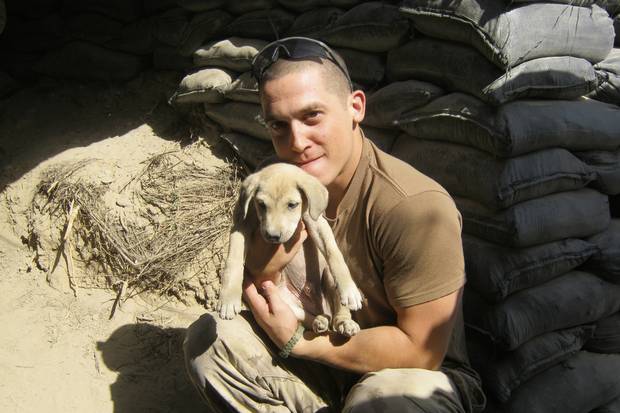

Mr. Kennedy with a local puppy in Kandahar, Afghanistan in November, 2010.

Photo courtesy Jonathan Kennedy

I am back in school, finishing my journalism degree in hopes of once again serving the public. I am also volunteering with a non-profit that helps homeless vets, and hope to work in veteran advocacy one day.

Through hours of therapy, research and books like Sebastian Junger's Tribe, I have come to understand the totality of what war does to a person, if you're lucky enough to survive. I have learned that the deep connections and bonds we made in the military and miss so much are the connections that elude so many of us in today's society. I know now that being a part of something bigger than yourself is what truly gratifies and brings us together. I look at my time in the military and overseas as a blessing, even though it has burdened so many of my days. I would do it all over again just to know what I know today.

Retired Private Jonathan Kennedy served with the 1st Battalion, Royal Canadian Regiment. He deployed to Afghanistan in 2010 and was part of Task Force 1-10.

If you would like your relative included in the commemoration project of Afghanistan war veterans lost to suicide, please e-mail

remember@globeandmail.com