Sherri Elms and her children Jake and Stephanie looking through old family photos at their home in Kingston.

Johnny C Y Lam/for The Globe and Mail

Sherri Elms was walking to her office when she received a much-anticipated e-mail from Canada Company, a charity that has the ear of the military and federal government and the backing of some of the country's most prominent business leaders and wealthiest people.

A pharmacist and military wife, she had inquired about the organization's scholarship program for children of fallen soldiers. Her husband, a respected infantry officer who did tours in Somalia, Bosnia, Haiti and Afghanistan, had died nearly five months earlier, on a chilly overcast morning in Kingston, in November, 2014.

The sudden death of Captain Brad Elms of the Royal Canadian Regiment shook many in the Canadian Forces. The country's top commander, General Jonathan Vance, then a lieutenant-general, flew in for his funeral.

"Your husband, and his enormous contribution to our nation, is an account of both great pride and tremendous tragedy for all of Canada, an account that very few Canadians will ever understand," read the first part of the e-mail to Ms. Elms from Canada Company president Angela Mondou.

Ms. Elms was told her inquiry was carefully considered. But the charity's three-member scholarship committee – which includes philanthropist Garfield Mitchell, Bay Street legal titan William Braithwaite and Canada Company founder Blake Goldring – concluded that her two children were not eligible for the education fund because the circumstances of her husband's death did not meet the organization's scholarship criteria.

The rub is this: Capt. Elms did not die a war hero in Afghanistan. The 51-year-old soldier, one of about 40,000 who served in Canada's longest military operation, took his life five years after returning from the Kandahar battlefront. He had been treated on and off for major depressive disorder for about a decade. His family believes he also had post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), but he never sought a diagnosis because he worried it would destroy his army career.

"It just crushed me that Brad's service was so discounted," Ms. Elms says, her children, Jake and Stephanie, by her side in their old brick house near Queen's University. "How is 33 years of service, four tours, any less honourable?"

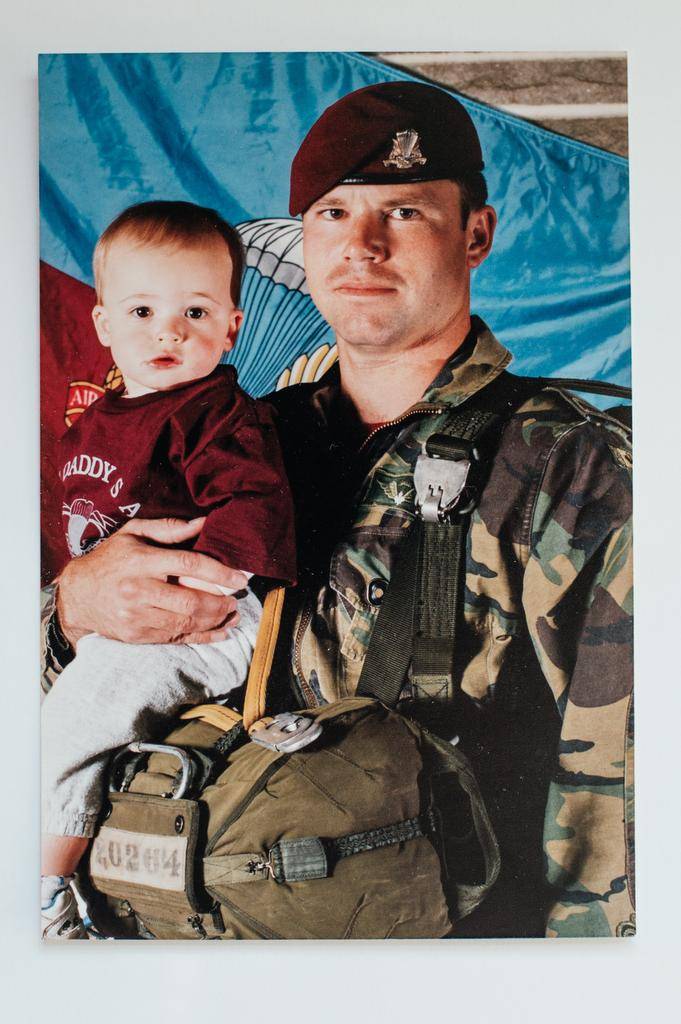

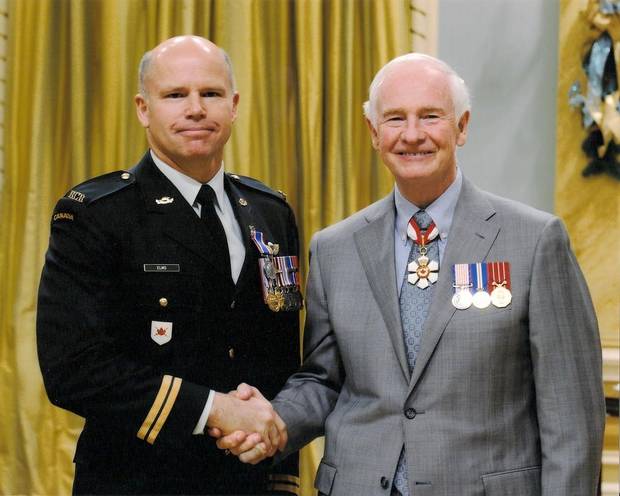

Captain Brad Elms and Governor General David Johnston.

Courtesy Sherri Elms

Capt. Elms is part of a growing list of casualties that had long been hidden. Officially, 158 Canadian soldiers died on the Afghanistan mission, which ended in 2014. What had not been public until recently was that at least 62 military members and veterans have killed themselves after returning from the gruelling operation, swelling the war's toll to 220, a continuing Globe and Mail investigation has found.

The Afghanistan mission was a contributing factor in some of the suicides, although it is unclear how many. A military board of inquiry determined that Capt. Elms' death was attributable to his military service. Veterans Affairs concluded his service-connected mental illness was "the underlying cause of his death."

Even so, the fact that Capt. Elms killed himself means his legacy and his family are treated differently in a number of ways. His name – and those of the 61 others – is not on Afghanistan war memorials. There is no grand public thank-you for their service or collective embrace for their loved ones' grief.

For Ms. Elms, the scholarship rejection from Canada Company landed like a sucker punch. She stood on the sidewalk and cried after reading the charity's e-mail on her phone on March 31, 2015. What stung was the message – and what it symbolized about military suicide. It made the family feel as if others thought the army captain's death was shameful, and that he was less of a soldier because he took his own life. The rejection seemed out of step with the Canadian Forces' evolving thinking on suicide and with the public's increasing awareness of PTSD. It was a harsh reminder of the discord between the ideal of military strength and the reality of mental illness.

"It was like rubbing salt into the wound," Stephanie, 21, says of Canada Company's decision. "They don't want to see this nitty-gritty suicide thing. It doesn't fit with the narrative of the glorified soldier."

No members of Canada Company's scholarship committee were available to comment to The Globe, after repeated requests over six weeks. Ms. Mondou, who was a captain in the air force and worked as a logistics officer in the former Yugoslavia and the Persian Gulf War, says the issue of suicide was not contemplated when the scholarship program was created in 2007, at the height of Canada's combat mission in Afghanistan. The query from Ms. Elms was the charity's first scholarship request from the family of a soldier who died this way.

Ms. Mondou notes that Canada Company's education fund is finite and was established specifically for children of Forces members killed while on a military operation. She adds that donors provided funding on the basis of this mandate, and that the scholarship program has not received government money.

"We have a commitment to our donors to support the children of Canadian soldiers who … have been killed while serving in an active role in a military mission, and we take that very seriously," Ms. Mondou says. The scholarship committee's decision was fully supported by the charity's board of directors, Ms. Mondou adds. Donors, she says, were not consulted about Ms. Elms' request.

Canada Company has made exceptions to its eligibility criteria in the past for children of parents killed in training mishaps in Canada and while on leave from overseas operations. The charity's education fund, valued at nearly $2.6-million at the end of 2014, is one of largest private scholarship programs for children of military members.

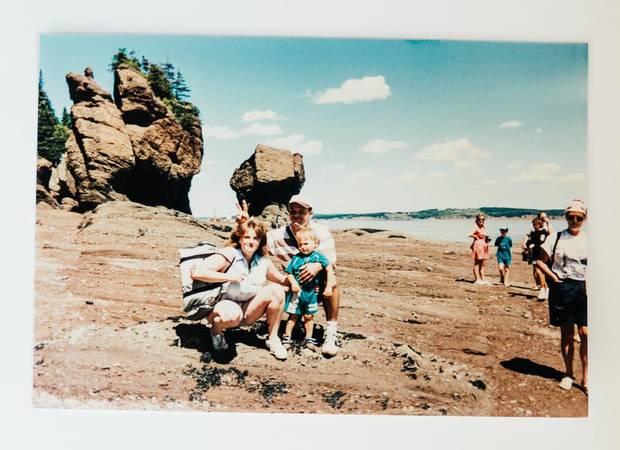

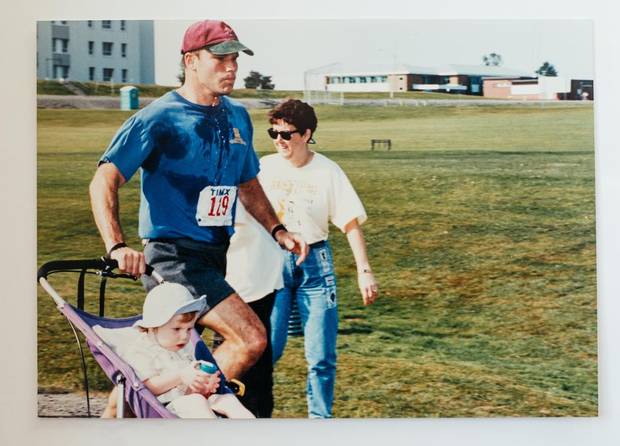

Family photo of Captain Brad Elms, his wife Sherri and his son Jake.

Reproduced by Johnny C Y Lam/Courtesy Elms family

The Globe surveyed 21 other private and government education-assistance programs available to children of fallen veterans and found that only one other – the Northern Alberta Institute of Technology's Fallen Heroes Scholarship – does not include students who lost a parent to suicide. In one other case – the Project Hero scholarship that is offered at about 60 colleges and universities and affiliated with Canada Company – the participating institutions have no common policy on inclusion of deaths by suicide.

Retired lieutenant-general Roméo Dallaire, a former senator and one of about 600 members of Canada Company listed on the charity's website, is urging the organization to rethink its scholarship position on service-related suicides.

"It is crass and has to be completely changed," he said while in Toronto for a screening of the Afghanistan war film Hyena Road. "The children of those who are suffering from PTSD are living in hell, and there is next to no support for them," he added. "You have an organization that could, in fact, pull them out of that and give them a breath of hope."

After Canada Company's rejection, the Elms family did not apply for other military-related scholarships. Ms. Elms says they just could not endure another battle after what they went through in Capt. Elms' final years, in which the proud and caring soldier, father and husband unravelled after his return from Afghanistan. He was, by the end, scarcely recognizable.

Broken bootstraps

Tall, smart and pragmatic, Brad Elms was also a tremendous athlete who won the army’s version of the Ironman race.

Courtesy Elms family

Capt. Elms was once a poster boy for the superhuman. At the age of 29, he won the military's version of the Ironman at the Petawawa base, northwest of Ottawa. The punishing race starts with a 32-kilometre run in combat boots and a 40-pound rucksack on the shoulders. Next, contestants must carry a canoe over their head for four kilometres and make their way to the Ottawa River for an eight-kilometre paddle before a six-kilometre push on foot to the finish – still in combat boots, still hauling the rucksack.

Capt. Elms was "a pull-yourself-up-by-your-bootstraps-and-get-on-with-it" kind of man, Ms. Elms recalls. "'That's how you win an Ironman,' he would say. 'Put one foot in front of the other and keep going – no matter what.'"

The couple were teenagers when they met on the dance floor of a bar near the Gagetown base in New Brunswick. Sherri McHarg, a bright, sweet-looking pharmacy student at Dalhousie University in Halifax, was visiting her father for the summer. Capt. Elms was a private then, fresh into his military career. The Ontario-raised soldier was tall, smart, eloquent and pragmatic. He was an emotional rock with a soft side, courting his future wife with song.

He enlisted in the army right after high school. He did not come from a rich military family background, but he had found a sense of belonging in the cadets program during a difficult stretch in his teen years. His first overseas deployment was to Somalia in December, 1992, with the Canadian Airborne Regiment. The country's residents were starving; a United Nations peacekeeping mission was organized to thwart the theft of international aid.

Canadian troops won praise for distributing humanitarian supplies and helping establish civilian police in their area of responsibility. But the horrific torture and killing of a 16-year-old Somali boy who had sneaked into a Canadian military compound cast a shadow over the country's efforts. Two soldiers were charged in the slaying and one was convicted of manslaughter. The federal government later disbanded the Airborne regiment.

The Somalia tour left a deep mark on Capt. Elms. He lost a close friend on the mission. Corporal Michael Abel was shot and killed on May 3, 1993, when a fellow member accidentally discharged his rifle while cleaning it. Capt. Elms was nearby, and Cpl. Abel had been like a little brother to him.

Cpl. Abel's death was one of several "emotionally traumatic events" that Capt. Elms was exposed to during his deployments, according to a partly censored military board of inquiry report on his suicide. Details of the traumatic events were blacked out in the 18-page report provided to his widow in August, 2015. What exactly he witnessed and experienced in Somalia, Bosnia, Haiti and Afghanistan is a mystery to his family. Like many soldiers, he did not talk about the harsh realities of war or peacekeeping with his spouse and kids.

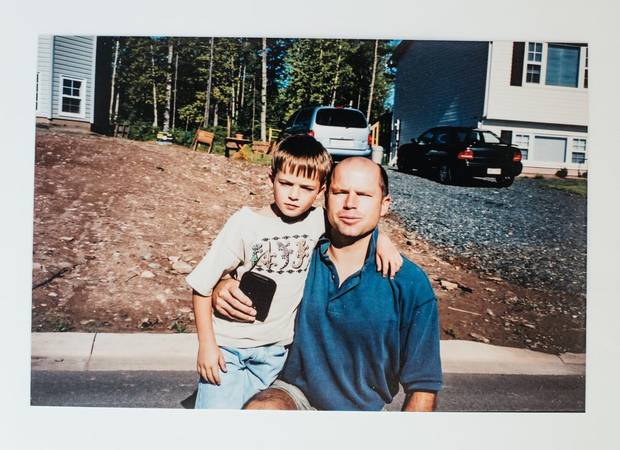

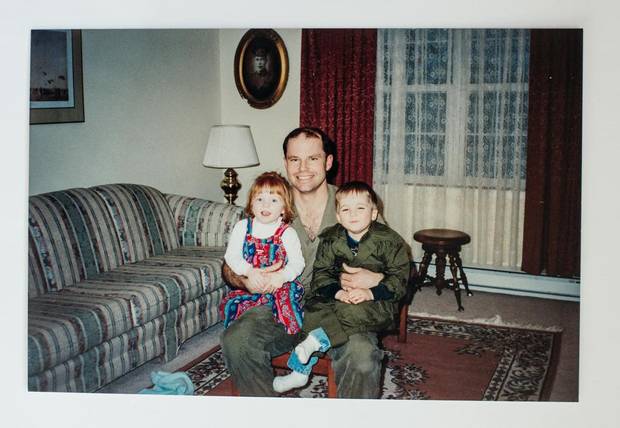

Captain Brad Elms and his son Jake.

Courtesy Elms family

Based with the Royal Canadian Regiment in Gagetown from 1994 to 2005, Capt. Elms was diagnosed with clinical depression after his Bosnia deployment. But it was not until he returned from a seven-month tour in Afghanistan in the spring of 2009 that his family noticed a big change in him. He started drinking heavily. His son and daughter, who were teenagers at the time, began tiptoeing around the house for fear of setting him off.

He would get angry at everything and nothing. He would yell if a cup was left on the kitchen counter or if the house did not look clean enough. Jake often intervened in screaming matches between his father and mother.

"I had to keep yelling him down," Jake, 23, remembers. "His reaction to things was totally disproportional to what was actually happening."

The honours student struggled to cope with his new home life. It became harder to remember the father that was. Capt. Elms used to take his children camping and hiking. He got them into running and helped them with their essays. He had encouraged them to excel, in and out of the classroom.

Capt. Elms never hit his wife or children, but he did not have to lay a hand on his family to hurt them. He was an imposing figure – husky with a deep voice. His words cut deep.

"The person that I grew up with and went camping with in New Brunswick was not the same person," his daughter explains at the family's dining table. "It wasn't because my dad suddenly realized he was going to be an asshole for the rest of his life. It was because he was so, so sick."

Dire choices

Eleven months before his death, Capt. Elms wrote a list of options for his future: divorce; no divorce, just leave and send money; get out of the military; stay; and suicide. Suicide was listed first.

He then wrote that he would never do any of the above because he was "a crazy, angry, abusive, fuck-up."

Ms. Elms found the note after his death on a clipboard in his woodworking section of the garage. "It was full of self-loathing," she says. She shredded the paper.

"He never felt it was his illness," his daughter notes. "He felt like he had done all this awful wrong in his life."

In his last year, Capt. Elms confessed to his wife that he had been thinking about taking his life. But he tried to dissuade her from mentioning it to his commanders. He told her, "You can't use the S word, Sherri, because if you use that, I will not be deployable. And then I might as well be dead."

Worried about his safety, Ms. Elms told his boss, padre, family doctor and friends that he was not well and was thinking about suicide. He denied it when they asked him. The weekend before he died, Ms. Elms wanted to take him to the emergency department for treatment. He told her to go ahead and try – he would just lie again.

Capt. Elms was smart, but did not have a diploma or a degree. He feared seeking help would end his military career and he did not know what else he could do for a living. About 15,000 members have been dismissed from the military for medical reasons since 2001, when the 9/11 attacks triggered the Afghanistan war. Some are too ill to work or have not found steady employment.

The battered captain began spending a lot of time at home in the final days of his life. He had left the family earlier that year for a woman about 15 years his junior with a young child. The relationship did not work out.

Captain Brad Elms and his daughter Stephanie during a marathon run.

Courtesy Elms family

The former Ironman winner and marathon runner looked drained. He sat in the basement and cried in front of his daughter. He had dropped about 30 pounds and was down to 167 pounds on his 5-foot-11 frame. "He was a shell of a man," his daughter says.

Capt. Elms' suicide stunned the military. He was a methodical and meticulous infantryman who polished his boots with ritualistic care. The inquiry into his death found that "he was respected by those he worked with and had a reputation as an intense and highly dedicated soldier."

But he also hid the true extent of his condition. The inquiry report notes that he minimized his mental-health concerns when dealing with his commanders and medical professionals to avoid a negative impact on his ability to deploy. He was worried about his future after the military and frustrated with his reversion to captain after filling in at the rank of major, the inquiry found.

"He was operationally focused and a significant part of his self-worth was tied to his life as a soldier and his ability to conduct operations," the report states.

Capt. Elms never received the urgent care he needed.

His family is working to come to terms with his suicide and years of living with his undiagnosed PTSD. All three are in therapy. They hope lessons from Capt. Elms' death will bring changes. They want the Forces to overhaul its post-deployment screening process for combat and peacekeeping missions. Instead of asking soldiers whether they are experiencing mental-health problems after an operation, the Elms believe the military should assume they are and treat them pro-actively.

They also want military doctors to involve soldiers' families in their care, so they can offer the truth if members lie about their mental health. Other families and veterans' groups have recommended this before, but privacy concerns have stymied change. Soldiers are treated by the military's medical system, while their families fall under provincial health care.

"He was, in his soul, a soldier's soldier. He kept going when nobody else could," says Ms. Elms, who works in the department of family medicine at Queen's. "They have to recognize that you train these people to be soldiers, so it's going to be harder to treat them. It's going to be harder to get to them. It's going to be harder for them to stop moving forward and admit that they have a problem, because you've trained them to walk until they die."

A lingering stigma

A military board of inquiry determined that Capt. Brad Elms’ suicide was attributable to his 33-year military service.

Courtesy Elms family

At the Toronto Market Exchange on a recent sunny morning, a group of bankers, traders and veterans' advocates gathered to set off the market's opening siren and announce a new scholarship program for children of military members.

The Wounded Warriors Canada education fund is the first in the country specifically designed for children of members with PTSD or other service-connected mental illnesses. Phil Ralph, the charity's national program director, hopes it will help children heal.

The fund has netted $40,000 in donations so far and is supported by The Bay Street Children's Foundation, CIBC, RBC and the Investment Technology Group (ITG). In the program's first year, eight children will receive up to $5,000 each for the first year of their postsecondary studies. Students whose parents died by suicide will be eligible.

"The stresses and things that these guys are going through when they come back sometimes will lead to suicide. I don't think there's any doubt about that, and that … shouldn't exclude any of their children," says James Duncan, who is director of sales and trading at ITG and founder of The Bay Street Children's Foundation, which helped launch the new scholarship program. Suicide, he adds, is "not a dishonourable thing, in my mind. This is another one of the problems that come out of battle."

Before Ms. Elms sent her query to Canada Company in February, 2015, she did her homework. She looked up the charity's previous scholarship winners. The organization appeared to apply a broad brush to the condition that a member must have been "killed while serving in an active role in a military mission" since Jan. 1, 2002. The organization granted scholarships to the children of a father who died in a moped accident in Greece while on a three-day leave from his Kosovo tour in 1999. In three other cases, exceptions were made for training accidents on home soil.

In all, the charity has awarded 87 scholarships to 33 children since its fund was established in 2007. Students receive up to $4,000 per year during their studies, for up to four years. Many of the recipients lost a father in the Afghanistan conflict – to suicide bombers, improvised explosive devices (IEDs) and firefights. The scholarship program has made a big difference in their lives and fostered a community among the children of the fallen.

"We have a lot of companies and organizations that say they support the troops, but some don't do anything," says scholarship recipient Jocelyn Ranger, whose father, Chief Warrant Officer Robert Girouard, was killed by a suicide bomber in Afghanistan in November, 2006. "Canada Company has been incredibly good to me and my family."

The Toronto-based charity has amassed an impressive list of influential members and financial backers in its decade of operation. Created at a time when Canadian soldiers were dying in theatre at a rate not seen since the Korean War, the organization has pledged to "stand shoulder to shoulder" with military members and to raise awareness in the corporate world about their work and sacrifices.

Captain Brad Elms and his children Jake and Stephanie.

Courtesy Elms family

The scholarship program was Canada Company's first major initiative. Financial supporters include CIBC, TD Bank Financial Group, Scotiabank, BMO Financial Group, RBH Inc., W. Garfield Weston Foundation, AGF Management, Barrick Gold founder Peter Munk, Paul Desmarais Jr. of Power Corp., and Jim Balsillie, the former co-CEO of Research In Motion and current chairman of the Council of Canadian Innovators. Senior military officials have attended Canada Company's scholarship ceremonies. So did Peter MacKay in 2012, when he was defence minister in the Conservative government.

The charity's focus has since expanded to include assisting released military members find civilian jobs. That program operates in partnership with Veterans Affairs and the Canadian Forces and has helped connect nearly 1,300 vets with jobs. The charity is also spearheading a federally sponsored program to convert decommissioned light-armoured vehicles into 250 monuments to be installed in communities across Canada. The armoured vehicles were used in the Afghanistan war.

Canada Company is one of many veterans' groups included in stakeholder meetings with Veterans Affairs. The Globe requested several times over six weeks, through charity president Ms. Mondou, to speak with Canada Company founder Blake Goldring, but did not hear from him. An e-mailed request was also sent to AGF Management, where Mr. Goldring is CEO.

Mr. Goldring, who is chairman of Canada Company's board of directors and a member of its scholarship committee, has received numerous honours for his charity work, including a meritorious service medal from the Governor-General and a Vimy Award from the Conference of Defence Associations Institute. In 2011, he was appointed the first Honorary Colonel of the Canadian Army.

Ms. Elms' scholarship query was reviewed by both the scholarship committee and the board of directors, Ms. Mondou says. All three scholarship-committee members are on the 12-member board. On March 12, 2015, Ms. Mondou told Ms. Elms in an e-mail that her request was a high priority for the charity and that a final decision would be provided in about two weeks.

On March 31, that decision was relayed: Stephanie and Jake were not eligible for the scholarship program because their father did not die on a mission. Suicide, Ms. Mondou explained to The Globe, was not part of the original mandate of the scholarship fund and never has been.

"The reality is we still have many children remaining who are eligible," Ms. Mondou says. "To expand beyond our current mandate could deplete the fund or impact those current children who are on the eligibility list as of now."

When the scholarship program was created, the charity estimated about 100 students would apply, based on the mission deaths in Afghanistan and the number of children left behind. With $346,000 in financial support already awarded to one-third of that group, about $2.6-million remains to support the others. The fund has grown over the years, from $1.7-million in 2011 to $2.6-million in 2014, according to Canada Company's annual reports.

Devastated by the charity's decision, Ms. Elms wrote to the ministers of defence and veterans affairs. In e-mails to Ms. Mondou, she pressed the charity for an explanation and told Canada Company its position ran counter to the message she had received from National Defence: that dying as a result of an operational stress injury, such as clinical depression or PTSD, was no different than being killed in an explosion on a mission.

"Your company motto is, 'Many Ways to Serve,'" Ms. Elms wrote to Ms. Mondou. "Well, there are many ways that service kills. My husband died in a way that no one speaks of – he took his life in Canada, close to home, and left more devastation in his wake than an IED on a roadside in Afghanistan ever could."

After her e-mails, and after e-mails and voice mails to Canada Company from the widow's friends, Ms. Mondou told Ms. Elms that Mr. Goldring had agreed to hold an urgent meeting of the scholarship committee to review its decision. Ms. Elms said the family did not want the case re-examined. Jake and Stephanie, who both just finished their third year of studies at Queen's, receive aid for their education from Veterans Affairs. Ms. Elms said she only applied for the Canada Company scholarship because a peer support worker suggested it. She told Ms. Mondou her children would not "beg for something that is not freely given."

Instead, she asked the charity to further explain its mandate and why it viewed suicide differently than deaths in combat and training. She urged the charity to include deaths like her husband's in its eligibility criteria. The Canadian Forces and Veterans Affairs had both determined his death was service-related, she told Ms. Mondou.

Canada Company's board of directors weighed Ms. Elms' questions and request, but the charity's position remained unchanged. Ms. Elms urged the organization to spell out its stand in its terms of reference so no other family would endure a similar rejection. And so the charity rewrote the terms of reference for its scholarship program last year, adding authorized training missions to its eligibility criteria. It also included this line: "Eligible candidates do not include children of Canadian soldiers whose deaths result from suicide."

The Elms family feels the charity's position further stigmatizes suicide and mental illness. More military members have taken their lives since 2002 –– at least 213 – than were killed in the Afghanistan war or in training accidents.

The Globe e-mailed questions to nine scholarship-fund donors listed in Canada Company's media releases, but most did not respond. Of the three who did, none answered the question of whether they support extending the program to suicides linked to military service.

A spokesman for CIBC, which kick-started the education-assistance fund with $1-million in 2007, said Canada Company has done "incredible work" delivering on its mandate.

"We recognize that the understanding of the needs and issues facing our military families continues to evolve," the spokesman, Kevin Dove, said in an e-mail. "We are proud of our affiliation with Canada Company and we will continue to engage with them as it continues to develop programs that support our military families."

Among the 22 education-assistance programs for children of deceased military members examined by The Globe, there is variation in how the words "active role," "active service" and "on duty" are viewed. Both Canada Company and the Northern Alberta Institute of Technology in Edmonton apply a narrow definition, saying a death must occur while the person is physically on a mission or at work.

Some, such as the Canadian Hero Fund and Brandon University's Afghanistan Mission Memorial Award, follow the approach taken by the Canadian Forces. If a suicide is determined to be "attributable to military service," it is also deemed as a result of "active service." Other scholarship programs do not ask how applicants' father or mother died.

The Project Hero scholarship program, which was started by businessman Kevin Reed and retired general Rick Hillier, a former chief of the defence staff, has been affiliated with Canada Company since 2010. Project Hero does not rely on a pool of donations, like Canada Company's program. Instead, about 60 colleges and universities have agreed to waive tuition for children of soldiers killed while serving on a military mission.

The Globe contacted all the schools listed as offering Project Hero on Canada Company's website. The survey showed that 15 would consider suicide deaths, while most said they were not sure whether suicides qualified. Several directed The Globe's questions to Canada Company.

Mr. Reed and Mr. Hillier said they would like children who have lost a parent to suicide included in Project Hero, although it is unclear who is responsible for modifying the program's criteria. Both are no longer involved in the administration of Project Hero.

"In my view," Mr. Hillier told The Globe in an e-mail, "those who commit suicide and it is deemed caused or contributed to by service to Canada, their children must be treated like those of casualties that are caused by direct physical action. Mental injuries are every bit as devastating as physical ones and we [should] look after their survivors in an appropriate manner."

Canada Company did not respond to questions on who would consider clarifications to Project Hero's criteria. Leah Jurkovic, spokeswoman for Colleges and Institutes Canada, said the advocacy group does not have an ongoing role in the scholarship program or in establishing the eligibility criteria.

"Certainly no one would be opposed to revisiting the criteria, but it wouldn't be our role to ask for this," she says.

Without the help of Canada Company and Project Hero, Ms. Ranger does not think she could have afforded to study business at Algonquin College. She was newly married with a young child and reeling from her father's death in the Afghanistan war. Canada Company also aided her two brothers with their education.

Ms. Ranger, a mother of three whose husband is in the military and served in Afghanistan, believes the scholarship programs that helped her should be extended to children whose parents have died by suicide.

"I just think with the prevalence of mental illness now in the military, it's something that needs to happen," she says. "As families of fallen soldiers, we know the jobs that they do and the pain that they suffer, and I really don't think a distinction should be made."