In the tidy port town of Lunenburg, N.S., near the ocean’s edge, a touching memorial lists the fishermen who have lost their lives at sea since 1890.

“Dedicated to the memory of those who have gone down to the sea in ships,” says the inscription on a slab of black granite, and to those who “continue to occupy their business in the great waters.”

The monument, across from the Fisheries Museum of the Atlantic and just down from the Fishermen’s Memorial Hospital, lists more than 600 names, with many surnames repeated, etched on three-sided stone columns. It’s a powerful reminder of the deadly toll suffered in one profession in one town.

Such memorials dot the towns throughout the South Shore. Not everyone is a fan. “I don’t like them,” says Stewart Franck, who led the Fisheries Safety Association of Nova Scotia from 2011 to his retirement in July. “They leave spaces for names to be added.”

Visits to half a dozen of them, from Lunenburg to Yarmouth, confirm he’s right – not only is there leftover space on each tablet, but some memorials, eerily, have entire blank slabs of granite ready to accommodate more names.

The monuments are a symbol not just of the severe risks of the job – but also of a prevailing sense of fatalism in an industry in which generations of fishers have gone out into the waters and, all too often, not come home.

Seagulls surround a fishing boat returning to Cheticamp Harbour with bait for crab traps in Cheticamp, N.S. at dusk on July 13, 2017. This is the day before the start of crabbing season. DARREN CALABRESE/THE GLOBE AND MAIL

That sense of inevitability – that accidents happen, and little can be done to prevent them – frustrates those like Mr. Franck, who are working to instill a safety culture in the sector. He calls the memorials “pessimistic.”

Such pessimism is one of many reasons that fishing, unlike other sectors, such as farming or mining, has seen little improvement in workplace fatalities over the years.

This may not seem surprising to those observing the profession from afar – after all, shows like Deadliest Catch and Cold Water Cowboys glorify the dangers of the job.

Danger may be all in a day’s work, but despite prevailing fatalistic attitudes of some who go to sea, the mystery is why there isn’t more oversight ensuring safeguards are in place. Why has fishing remained so deadly, in an era when other industries have gotten safer?

Fishing deaths

1999 2000

2000

A risky business where bravado can be the enemy

Despite strides in workplace safety, across Canada, and across industries, on-the-job deaths occur with disturbing frequency – almost every day, someone dies from a traumatic, work-related injury.

Assessing which jobs carry the most risk, however, is a murky business. In such countries as Australia, the U.S. and Britain, worker fatality rates are produced and published every year. But the Association of Workers’ Compensation Boards of Canada doesn’t produce such numbers, and Statistics Canada has not done so since 1996.

The Globe and Mail set out to fill that gap, and answer a simple question: What is the most deadly work in Canada?

The answer matters. Awareness of which jobs put people at most risk, and which are growing more dangerous, can help spark better policy and aid in the enforcement of occupational-safety targets. What’s more, it can improve workplace practices and training, and ultimately save lives.

A months-long data project conducted by The Globe and Mail with Statistics Canada reveals that fishing has the single highest fatality rate of any sector in the country. Among individual occupations for which data are available, fully three of the top six most deadly jobs – deckhands, fishermen and marine harvesters – are in fishing.

The 10 occupations with the highest average (traumatic injury) fatality rates, 2011-2015

THE GLOBE AND MAIL » SOURCE: STATISTICS CANADA, AWCBC

Those statistics, based on workers’ compensation data and Statistics Canada employee numbers, were gathered, produced and analyzed by a team of Globe journalists in conjunction with Statscan. The statistics focus, intentionally, on rates – not absolute numbers – in order to expose which jobs and industries carry the highest risk of dying at work. Fishing is a relatively small sector – even by generous estimates, less than one half of one per cent of the Canadian work force, though still the lifeblood of many coastal communities – but it is responsible for a disproportionate share of on-the-job deaths.

To put that risk into context: Being a deckhand is 14 times more deadly than being a police officer – a job widely perceived as dangerous, and whose on-the-job fatalities garner much public attention.

Average fatality rate for deckhands and police officers, 2011-2015

THE GLOBE AND MAIL » SOURCE: STATISTICS CANADA, AWCBC

If anything, fishing fatalities are undercounted: Not all deaths are included in the official workers’ comp death counts, because not all fishermen (also called fish harvesters, or fishers – about 80 per cent of people who work in the industry are men) are part of the workers’ compensation system – the self-employed aren’t fully covered in every jurisdiction in Canada, so they may be underrepresented in the stats. And in New Brunswick and Prince Edward Island, for example, workers’ comp exemptions mean fishing deaths may not be fully counted.

The workers’ comp data show 27 deaths in the fishing sector, nationwide, due to traumatic injuries, between 2011 and 2015, the most recent year for which national data are available. A more complete tally, in the marine database of the Transportation Safety Board of Canada, an agency that investigates marine incidents and issues safety recommendations, reveals almost twice as many deaths – 52 fishing fatalities in that time period.

Since 1999, more than 200 fishermen in Canada have lost their lives on the job, the TSB’s database of marine incidents shows. That works out to one death in the fishing sector, on average, nearly every month. Because many fatalities occur in isolated areas, one at a time, they are mostly unpublicized. Some of those who lost their lives were young – a 17-year-old died on his very first day aboard a commercial fishing vessel in Manitoba; a 21-year-old captain went missing with his young crew in a storm in Nova Scotia; in B.C., a 25-year-old drowned on his first day of setting prawn traps. Last year, three generations of men from a single family lost their lives when a fishing boat sank in Newfoundland.

A second leg of The Globe’s project explored why fishing has not seen improvements in on-the-job fatality rates. Although the annual death count has fallen slightly in the industry in recent years, there are also fewer fishermen. The bottom line: Proportionally, the risks haven’t much diminished.

Interviews and scrutiny of Transportation Safety Board reports reveal a litany of problems, from slow-to-be-enacted safety regulations to a lack of enforcement and inspections, as well as an absence of safety training on boats. Some deaths occur when fish harvesters fall overboard after a vessel is overloaded with catch, and they aren’t wearing a personal flotation device. In some cases, captains bear responsibility for failing to prioritize safety procedures.

“We’re moving at great strides in the right direction, but can we prove it statistically yet? We’re struggling with that still,” says Glenn Budden, the Vancouver-based senior marine investigator at the TSB – an agency that has issued more than 40 fishing-related safety recommendations since 1993, some of which have gone unheeded for more than two decades.

Mr. Budden fished for 35 years, and feels both frustration and anguish, sometimes to the point of tears, at the slow pace of change. These deaths, he says, are not inevitable.

Fishing poses unique challenges for policy-makers and safety advocates. It’s an industry composed mostly of small, independent owner-operators, often in remote locations, with fewer large employers, health-and-safety committees or big unions that have typically pushed new safety measures in other sectors.

Locals walk down a laneway as a fishing boat pulls into Cheticamp Harbour in Cheticamp, N.S., an Acadian fishing community on Cape Breton Island, at dusk July 13, 2017. DARREN CALABRESE/THE GLOBE AND MAIL

Mr. Franck has worked in other industries, such as mining and manufacturing, and seen safety improve: In mining, dust is better controlled, and personal protective equipment has improved; in factories, safety precautions have been tightened on assembly lines. Those changes have not yet, however, taken root in fishing, he says. “I don’t want to speak negatively about our industry, but in some aspects,” he says, “we are 100 years behind.”

Follow-up in the wake of fatal accidents can also be lax: A job-related death in other sectors triggers a stop-work order; the work site is shut down, investigations are launched. In fishing, often, “there are no repercussions,” says Mr. Budden.

At the federal level, Transport Canada has regulatory authority for fishing-vessel safety. The TSB’s mandate is to advance transportation safety and make recommendations, some of them aimed squarely at Transport Canada; sometimes the two don’t see eye to eye.

This summer, new fishing-vessel safety regulations issued by Transport Canada took effect, aimed at improving safety outcomes – the first update to such rules in more than four decades. They contain new requirements for written safety procedures, safety equipment and vessel stability, and followed 14 years of consultation with industry.

Still, the regulations, which took effect in July, “fall short of what we had hoped for,” says TSB chair Kathy Fox, although she adds that the board recognizes that the regulator has to consult with various players. Thirteen of its fishing-related recommendations are still outstanding, the oldest of which - that Transport Canada require the carriage of survival suits on all vessels - dates to 1993.

Some fishermen have ferociously opposed the new rules, saying they are costly, onerous and ineffective – while some safety experts say the changes don’t go nearly far enough.

Regulators, meanwhile, can’t police every boat. All of which leaves them faced with what is, in many ways, a psychological challenge: How does one instill a culture of safety in a sector known for its independence, bravado and fierce sense of competition? “I’ve been in safety for 30 years or more,” Mr. Franck says, “and I’m still trying to find how we get people to do the right things because they want to, not because they have to.”

Mr. Budden agrees that regulations alone aren’t enough: “It’s changing that attitude that’s been in place for such a long time. And part of it is the old rough-and-tumble fishermen, [who say] ‘If the sea takes me, it’s an honourable death.’ God, it doesn’t need to be that way.”

Fishing deaths

2001 2002

2002

External pressures, and tragic choices

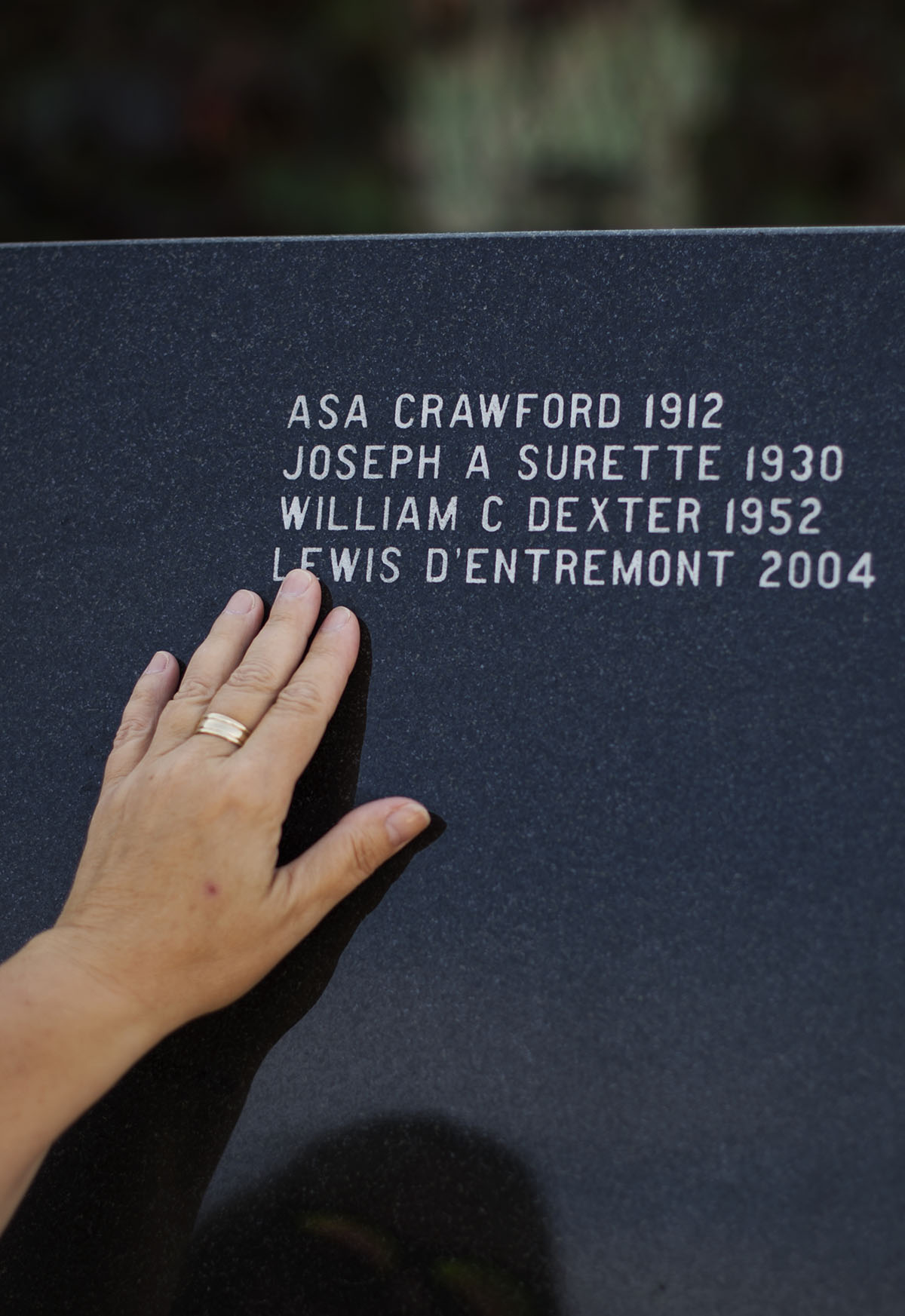

Bereaved family members like Marilyn D’Entremont are among a growing legion of people who are now pushing for safety.

Lewis D’Entremont DARREN CALABRESE/THE GLOBE AND MAIL

For her, the horrible news came at 10 p.m. on Sept. 23, 2004, a calm night under a harvest moon. A neighbour, who was an RCMP constable, pulled up in her police cruiser and knocked on the door. In tears, she told Ms. D’Entremont that there had been an accident at sea. Her husband, Lewis – a kind, gentle man who loved nature and campfires, cycling, and spending time with his three children – was not coming home.

He died at sea, knocked overboard from a commercial fishing vessel while catching herring at night, in darkness: A piece of equipment was broken, so Lewis, a fishermen with more than 30 years’ of experience, had taken on the dangerous job of manually moving a heavy cable at the back edge of the boat.

“I still miss him, every day,” says Ms. D’Entremont of her high-school sweetheart, in an interview in Pubnico, an Acadian fishing village at the southern edge of Nova Scotia. “My son never had a chance to share a beer with his dad; his dad never saw him graduate. My daughters will never have their dad walk them down the aisle. My husband isn’t around to see our grandson. It changes your life forever.”

DARREN CALABRESE/THE GLOBE AND MAIL

And his death was preventable, she believes: If the equipment hadn’t been broken in the first place, Lewis wouldn’t have been pulled into the water. If he’d had a life vest on, he could have been saved once overboard.

She now goes out on wharves and attends industry events to talk to fishermen about safety culture.

Not that those listening aren’t aware of the perils they face. Ask many fishers about whether their job is dangerous, and a common response is: Of course it is. We know. It has long been so. The history of fishing is strewn with dead bodies and missing persons. In two devastating back-to-back seasons – 1926 and 1927 – the “August gales” hit fishing schooners off the Atlantic Coast, pounding Nova Scotians especially hard. More than 130 people lost their lives.

Newspaper headlines from 1926, on display at the Fisheries Museum of the Atlantic, after the “August gales” slammed the coast of Nova Scotia.

Seven decades later, when Statistics Canada published that detailed analysis on worker fatality rates – the agency has not published one since then – it called the fishing industry “the most dangerous in which to be employed.”

Yes, some factors are helping mitigate risks at sea: more accurate weather forecasts, sophisticated navigational tools, reliable communications, advances in safety gear. And at least some more fishermen have embraced safety measures. Even so, fishing-vessel fatalities remain “unacceptably high,” says Ian Campbell, manager of design and equipment standards for fishing vessels at Transport Canada, who oversaw the creation of the updated safety regulations. And their impact is felt with a particular severity on the East Coast, home to three-quarters of fishing activity in Canada.

Along with the unbending reality of geography, ever-evolving consumer tastes have played a role in elevating fishermen’s occupational risk. Diners these days want their lobster and fish to taste freshly caught; as a result, catches are sometimes stored on boats in liquid tanks, which, when only partly filled with sloshing water, can affect a vessel’s stability. This “free surface effect” raises the risk of capsizing (a risk the new regulations aim to mitigate).

And while reality shows tend to single out particular aspects of fishing, such as the harvesting of Alaskan king crab, as being especially deadly, all types of fishing carry dangers. And it’s not, as in The Perfect Storm, just turbulent seas that cause fatalities; fishermen are also dying in perfect weather conditions.

That said, climate change is conjuring decidedly less predicable, and more severe, weather at sea. And as some fish stocks become scarcer, there is a temptation for fishermen to head further out – where water is colder and choppier, and where help, when needed, is distant. “One of the biggest increased risks is going further and further from shore to get the best fish,” says Mr. Campbell. “When there was abundant cod locally, nobody needed to go far.”

Other factors are ones as old as the industry itself: overloaded vessels, poor risk assessment, and do-it-yourself modifications to vessels, which can alter their stability. “We have people that are going out and making modifications to their boat in the backyard,” says Mr. Franck, by “putting on a huge superstructure, switching from a lobster-fishing boat into a dragger. And now the characteristics of that boat’s stability have changed.”

Fishing deaths

2003 2004

2004

Also on-board: fatigue and substance abuse

A bit like the net of a fisherman that’s been repaired on the fly, the responsibility for fishing safety is a patchwork in this country. As a result, oversight can slip through the cracks. Although Transport Canada is responsible at the federal level for fishing-vessel safety, it has no mandatory inspection program for smaller vessels, which constitute the majority of Canada’s fleet.

Provinces, meanwhile, largely oversee workplace health and safety regulations. One result: a wide variation in approaches. In New Brunswick, for instance, fishing vessels aren’t considered a “place of employment”; as a result, they are not subject to workplace legislation, and the province’s regulator, WorkSafeNB, does not have jurisdiction over them. Aboard vessels themselves, fishing masters are responsible for their crew’s safety. But some captains don’t consider themselves employers, and thus feel exempt from responsibility, says Mr. Budden.

The new federal safety regulations introduced by Transport Canada in July don’t address several crucial issues that affect safety, notes Mr. Franck. Fatigue, which impairs judgment, is chief among them: There are frequent stretches when the captain or crew may get next to no shut-eye. Fishermen have told the Transportation Safety Board that insufficient sleep and variable rest schedules are commonplace.

In 2012, the board published a sweeping four-year study on fishing safety. A team of investigators consulted more than 300 fishermen, industry and union reps, regulators and safety trainers, and explored why fishing deaths persist, and what ought to be done to save lives. The study cited some fishers who report sleeping as little as two or three hours a night for up to six straight nights. Between 1999 and 2008, the TSB recorded 89 cases of fishermen falling asleep while operating a vessel.

In the trucking industry, for instance, a tired driver can pull over and grab some sleep. But “if your fishery is only so many hours, the reality is you’ve got to work with the hours that you’ve got. You can’t just fall asleep in the middle of the ocean with a catch of fish,” notes Ryan Ford, program manager at Fish Safe B.C., an industry-driven safety program.

Crab harvesters at the wharf in the early hours of the season's first day in Cheticamp, N.S. on July 14, 2017. Conditions are calm, but even so, the dangers are ever-present. DARREN CALABRESE/THE GLOBE AND MAIL

Drug and alcohol abuse, says Mr. Franck, also pose genuine threats to safety. Research has shown a high prevalence of addiction among seafarers, including fishermen, fuelled in part by the stress that comes with isolation, dangerous situations, pain, and a desire to combat fatigue. The TSB cited marijuana use in its report on a 2012 collision between an American and a Canadian fishing vessel in which one crew member is presumed to have drowned.

The TSB also said, in its 2012 safety report, that it recorded 15 fishing-related incidents between 1999 and 2008 involving alcohol, resulting in a total of five fatalities. Says Mr. Franck, “If I go to industry and say, ‘What can we do better to improve safety in the fishing industry?’ … they tell me that as many as 30 to 70 per cent of the fishing vessels have drug and alcohol problems.”

Fishing deaths

2005 2006

2006

A fierce storm, and financial pressures

Capt. Kat’s Lobster Shack serves fresh seafood daily in Barrington Passage, in southwest Nova Scotia, in a county that bills itself as “the lobster capital of Canada.” The restaurant’s nautical-themed entrance has a lobster trap, a ship’s wheel – and a framed picture of the smiling young seafarer for whom the restaurant is named: Katlin Nickerson.

He and his entire young crew aboard the Miss Ally went down in a massive storm in February, 2013, while fishing for halibut. The conditions were terrible: hurricane-force winds, and waves more than 10 metres high. Other fishermen had turned back. But the men on the Cape Islander vessel stayed out in the stormy waters as they worked to retrieve their gear. The Miss Ally’s lights had broken, and the crew was in utter darkness – in the same moments that a nearby weather buoy was registering a rogue wave measuring a staggering 18.6 metres, or 61 feet.

Their five bodies were never found. The men were well known. People in the surrounding communities were devastated. But the TSB didn’t conduct a full-blown investigation of the sinking, concluding, after some initial examinations into the disaster, that it couldn’t identify factors that would advance safety. It was a decision that drew criticism from those in the province who wanted answers.

Mr. Nickerson was just 21. His mom, Della Sears, sits in a quiet corner of the restaurant she now co-owns. It’s been four and a half years since that deadly night. The pain is still raw. “I think about him every day, all day long,” she says. “I wish he’d walk in that door.”

With $700,000 in debts to finance a boat, gear and lobster license – in a year of plunging lobster prices – Mr. Nickerson was trying to pay the bills by winter fishing. “Katlin was young, and he was fierce, and he was not afraid of work,” she says. “He was just trying to make a living.”

Though there were immersion suits aboard (which can protect a wearer from hypothermia), it’s unclear whether they were used.

Like Ms. D’Entremont, Ms. Sears hopes to see change come from her loved one’s death. For starters, she’d like to see safety gear become the norm. She also would like to see fishermen wear small personal tracking beacons, in case they fall overboard. While such beacons might not save fishers, they would help bring the bodies home when the worst has happened.

Ms. Sears’s wrist is tattooed with her son’s name, as well as the latitude and longitude of his last co-ordinates, and the time the emergency signal on his boat went off: 11:06 pm.

Just over the causeway, in nearby Clark’s Harbour, on Cape Sable Island, the wharf is shrouded in thick fog. Two young men are checking their gear, which includes harpoons and darts. They are jonesing to go swordfishing, the moment the fog lifts. They know all the young men who died on the Miss Ally. One of these men was even out on the rough waters the next day, searching for the lost men, in vain.

As for their own determination to continue their livelihood on the sea, they say they try not to think about the dangers. “It’s risky,” says one, shrugging. “Accidents happen.” His companion tells the story of once being dragged overboard by a rapidly unspooling rope. It was a close call.

But neither man is willing to wear a life vest. They’re hot, they say, and uncomfortable. (This is true of the older versions; newer designs of personal flotation devices, or PFDs, which can cost as much as $400 a piece, are made to be less obtrusive). When asked how they view Transport Canada’s new safety regulations, the answer is short: “Bull.” One of the joys of their job, they say, is that when they’re out on the water, no one can tell them what to do.

It’s the kind of attitude that exasperates Stewart Franck. He took over the helm of the Fisheries Safety Association in 2011, soon after the introduction of an annual levy on the industry of up to $200 to promote better safety in the sector. The move was so widely reviled that Mr. Franck experienced both legal threats and promises to burn down his house. But the cost of that levy, he says, has been more than offset – improved safety outcomes since that time have led to reduced workers’ comp premiums, saving employers money in reduced payments.

Mr. Franck wearily points to a Facebook fight from earlier this year that exemplifies the resistance he has encountered. The May 31 entry, on the Safety Association’s page, starts with its post of a news photo of lobster fishermen at work on a boat. An accompanying caption notes that none of the crew is wearing a personal flotation device, and says there is still “a LOT of work to do to promote safe attitudes and behaviours in the NS fishing industry.”

Among the responses posted: “Some of this safety stuff is just a money grab.” “All the safty gear in the world is not gonna stop the odd accident from happening … you cant bubble wrap the whole world.” “While you are talking safety, maybe they should enforce no drugs or alcohol.” “Fine me all they want, I ain’t wearing [a PFD] on the wharf.”

Such attitudes are not universal, but where they exist, chipping away at them takes time. Still, it’s happening in at least some parts of the country. British Columbia has become a leader in encouraging safer practices among fishermen. The province has regulations specifically geared to the commercial fishing industry, and WorkSafeBC conducts inspections and accident investigations. Since 2009, Fish Safe B.C. has offered free safety training; more than 2,500 commercial fishermen – skippers and crew – have participated so far, and its Safest Catch program is now being piloted on the East Coast. Fish Safe also runs a “Real Fishermen” campaign, featuring posters of manly fishers wearing their PFDs.

While at some wharves in Nova Scotia nearly all fishermen now wear such devices, at others, the figure is more like 20 per cent – or even lower, says Mr. Franck. And it is a figure that may prove difficult to budge. In Shelburne, Gary Dedrick, who has fished for almost five decades – since the age of 12 – and once survived hypothermia after falling from his boat into winter waters, points to the names on the fishermen’s memorial of the 15 men he knew. He describes government regulations as “bureaucratic stuff that doesn’t make any sense.”

Says Mr. Dedrick: “Any type of fishing you do, there’re moving parts on that boat, it’s always moving. When your workplace is moving and the equipment is moving, there’s a chance of something happening.”

Fishing deaths

2007 2008

2008

Knives, ropes, roaring motors

It’s 4 a.m. on the first day of snow-crab season on the Hurricane Henry, a 39-foot, orange-and-white fishing boat. On this calm morning in mid-July, in the predawn darkness, Andrew Bourgeois, the vessel’s 25-year-old captain, casts his boat from the wharf in Cheticamp, Cape Breton Island, a Globe and Mail reporter and photographer in tow.

Conditions could not be better: clear skies, the smallest of waves, gentle breezes.

And yet even on the most sublime of days, there are astonishingly hazardous moments: The roar of the motor can make it hard to hear: A man-overboard splash, or a cry for help, can easily go unnoticed, especially in the dark.

DARREN CALABRESE/THE GLOBE AND MAIL

Eight kilometres out, the crew will retrieve the crab traps, empty them, insert new bait of squid and mackerel, and toss them back again. To begin this process, a heavy boom swings around, used to raise and lower ropes with the crab traps attached.

TAVIA GRANT/THE GLOBE AND MAIL

The swaying, crab-laden pots must be hauled over the edge of the boat and onto the deck. They are so heavy – about a thousand pounds, or 450 kilograms, apiece – that even on a stable boat, the centre of gravity shifts. Sometimes, those traps can get caught, or a rope breaks, and they fall on anyone below.

TAVIA GRANT/THE GLOBE AND MAIL

(“If it hits you, you’re done,” says crew member Joel Camus.)

A crewman then wields a large knife to pry open the on-board hatches where the crab will be thrown – gaping holes in the deck. Sharp steel plates wall in the crabs.

TAVIA GRANT/THE GLOBE AND MAIL

To rebait the pots, an agile crew member named Matthew Bourgeois – Andrew’s cousin – climbs up onto an empty cage, and lies across the top of it, as it hovers over the water.

TAVIA GRANT/THE GLOBE AND MAIL

The rails of the boat are low, less than a metre in height – good for fishing, bad for keeping people on board when a rogue wave hits. And many boats operate with just two members: The captain, in the wheelhouse, may not immediately notice if the deckhand has been caught in a rope.

Ropes themselves are a danger (to both fishermen, and, scientists have noted recently, to right whales). When the baited crab trap is thrown back into the sea, the rope uncoils rapidly. One errant crew member’s foot, an inch too near that rope, can pull him in and drag him under.

DARREN CALABRESE/THE GLOBE AND MAIL

Ropes can also get tangled or knotted, and unsnarling them can lead to trouble. The Globe heard countless stories of ropes, caught on a leg or piece of clothing, that had pulled people overboard. Some of those people survived, especially those who wore a flotation device; others did not.

On this day, the three-man crew wear PFDs most – but not all – of the time.

DARREN CALABRESE/THE GLOBE AND MAIL

They work at breakneck speed; their choreography is beautiful in the morning light.

To be sure, other workplaces house heavy equipment and involve loud noises and sharp edges and even holes underfoot. None, however, have a floor that never stays still, bouncing and heaving: zigzagging through the sea.

DARREN CALABRESE/THE GLOBE AND MAIL

Add to that ice that’s meant to keep the crab cool, spilled from a shovel, and now melting underfoot. To say nothing of runaway crabs and loose ropes – all with the unforgiving ocean just a step or two away.

DARREN CALABRESE/THE GLOBE AND MAIL

And all this on a summer day. As boats ice up in winter, the risks can multiply exponentially.

But where a landlubber might see jeopardy, those who work this life often frame their jobs in terms of adventure. “I got a passion for it,” says Mr. Camus, 54, whose mother tongue, like that of his crew mates, is French. “In 41 years, no two days are the same. The elements of weather. You see birds, whales. Every day is new.”

Mr. Camus focuses on those upsides despite having seen his share of tragedy. One man he knew fell into cold water while setting lobster traps a few years ago. The captain grasped his outstretched hand in the water, but then had to let it go. The man drowned.

And of course, there are the financial rewards. When the fifth and final trap is hoisted today, it is brimming with crab: more than 1,100 pounds (or 500 kg), worth about $6,500.

It will go to the United States and as far as Japan and China, where demand for seafood is booming. High prices have made fishing lucrative for some people in recent years – as evidenced by expensive pick-up trucks and large new houses that dot some villages. For those with limited education, living in towns with few other well-paid job opportunities, the pay outweighs the perceived risks.

Fishing deaths

2009 2010

2010

A hesitation to impose change

For the Transportation Safety Board’s Mr. Budden, the danger that comes with every catch hits close to home. His father died at sea; he himself has fished from the age of 15. In the course of nine marine investigations that he has conducted at the agency, he has sat with many bereaved family members, and listened firsthand to their grief.

Decades of in-depth TSB investigations show that nearly all fishing deaths are preventable, he says. The attitude that fatalities are an accepted job risk, he adds, “is wrong, and that needs to be addressed” – and could be, in many cases, by fishers simply wearing a personal flotation device.

But requiring that fishermen wear such devices at all times while on deck – as well as insisting on stability assessments (with clear guidelines on how much weight the boat can carry) for all boats – is something that Transport Canada seems reluctant to do. That’s in part because the department is keenly aware of the challenges the industry faces. “Fishing is a key industry in Canada and it’s a livelihood in many parts of the country,” says Transport Canada’s Mr. Campbell. “So, the department had to be very clear that it was taking into account the impacts, that there may be some costs associated with safety, and that those were well taken into consideration, so that there would be no unnecessary burdens on the industry folks.”

The TSB has noted that the average time between Transport Canada accepting a safety deficiency and final implementation of a regulatory change is 13 years. “Transport Canada has been slow,” says TSB chair Fox, in addressing outstanding recommendations.

As long as Transport Canada doesn’t require fishermen to wear PFDs at all times when on deck, the TSB noted in July, “there is an increased risk of fatalities when fishermen fall overboard.”

For his part, says Mr. Campbell of Transport Canada, “You’ve got a wide and varied industry, made up of small operators. It’s different in the logging or mining industries, where you have larger corporations [that] tend to acknowledge quicker the risks and the liabilities that they absorb for employees.” In fishing, he notes, “you’ve got small-vessel operators who don’t often understand the obligation that they have. And there’s the national nature of it. Across the coasts, we have over 20,000 fishing vessels in this country … there’s difficulty in accessing fishermen to talk to.”

Certainly fishermen have sometimes been angered by what they see as government overreach. Tensions are such that some East Coast fishermen stormed out of meetings with Transport Canada earlier this year, saying they needed more time and clarity on the new regulations. Some cited concern about the cost of buying new equipment.

Transport Canada has not been communicative enough, they say, in its dealings with a sector in which messages are more effectively conveyed on the wharf than by posting notices on websites – in PEI, long-time fisherman Craig Avery estimates about half of fishermen in the province “still are not schooled on the Internet and computers.”

To others, the issue is an even broader one involving communication: Regulators can play a key role in bolstering safety, they say, but ultimately, it’s a shared responsibility, says Ms. Fox. “As long as all the stakeholders don’t work together to reduce the risks of loss of life,” she says, “we’re going to continue to see fishing fatalities, many of which are preventable.”

Fishing deaths

2011 2012

2012

A plea from those left behind

When she speaks to fishermen’s groups, Marilyn D’Entremont asks them: “Who do you have at home that’s waiting for you? And sometimes they’ll answer, ‘My daughter’ or ‘My wife.’ I say, ‘Well, wear a PFD for her. If you don’t wear it for yourself, wear it for your children and your loved ones. Because they are the ones who are going to miss you, if you don’t come home. It’s as simple as that.’”

Widow Marilyn D'Entremont is reflected in the memorial for those 'Lost to the Sea' where her grandfather's and husband's names are among the thousands etched on the monument in Yarmouth, N.S. DARREN CALABRESE/THE GLOBE AND MAIL

Ms. D’Entremont is not alone in pushing for change. Near Halifax, Heather Crout has channelled her grief over losing her husband, Scott, who went missing (and is presumed drowned) while fishing for herring in 2009, into targeted actions to prevent more deaths. She painted and sold 10 watercolour pictures of stages of Scott’s life at sea. With the proceeds, combined with donations and money she gets from speaking on workplace safety, she buys those high-tech $400 life vests, and gives them to local fishermen – 23 in all, so far.

And broader change is afoot from some unexpected quarters, driven in part by the attitudes toward safety in other sectors. In Newfoundland, a province that has beefed up safety training, Roy Gibbons, a fishing-masters instructor and former fisherman, says a stronger sense of safety practices is prevalent in young workers – especially those who have spent time in the oil patch.

“There’s been a cultural shift. We’ve got a lot of fishermen who’ve gone out to the oil fields of Alberta, and a lot of them are back now because of the drop in oil. And what we’re seeing is that they’re coming back with a safety culture that they didn’t go away with…They come on board a boat and they don’t mind wearing a hard hat or safety glasses. As a matter of fact, they got all their own gear, a lot of ’em.”

Fishing deaths

2013 2014

2014

Consumers offer hope

Consumers may not connect the lobster roll on their plates with the deadly toll it takes to get it there. But they do, increasingly, want to know more about where their seafood comes from and how it was caught. “One of the keys to our business is connecting our customers with the fishery,” says Kristin Donovan, co-owner of fishmonger Hooked, which now has four locations in Toronto, and which focus on responsible fishing practices and in cultivating “direct relationships between fisher and consumer.”

The Marine Stewardship Council, meanwhile, a non-profit organization that promotes sustainable fishing practices, is introducing labour practices to its process of certifying seafood supply chains. Starting next year, the council will require certified fisheries to declare they are free from “unacceptable” labour practices, and ask them for evidence to support this claim. Although its current focus is on forced labour, it sees growing interest from retailers in social-welfare issues within the seafood market.

A global survey it commissioned last year found that Canadian consumers are willing to pay more for sustainable fish sources; and two-thirds of respondents said they wanted more “traceability” that shows their seafood comes from a trusted source. More than half were concerned “that the fish they buy comes from a company that does not care about working conditions.”

Consumers increasingly want to know the story behind the fish, Ms. Donovan says – what the fishery is like and who caught the fish. Any sense that an operation doesn’t treat its workers well or blatantly disregards health and safety issues “definitely would affect our buying choices” she says.

Fishing deaths

2015 2016

2016

Early signs of on-board change

Fishing is a hierarchical operation – the crew follows the skipper’s orders. This has sparked some innovative ideas aimed at incrementally changing attitudes. When focus groups for WorkSafeBC showed that the skipper sets the tone on the boat and that they can influence whether the crew wears life vests, the organization took inspiration from the fact that fishermen often play a few rounds of cards at sea – and created a pack of playing cards. The front of each face card shows the skipper and crew, all happily sporting PFDs.

Some captains, meanwhile, keenly aware that they are responsible for on-board safety, are leading by example. In Cape Breton, Leonard LeBlanc is one of them.

Retired fisherman Leonard LeBlanc sits at the wharf in the Cheticamp Harbour in Cheticamp, N.S., not far from where an accident aboard his fishing boat took the life of his five-year-old son. DARREN CALABRESE/THE GLOBE AND MAIL

People laughed when he started wearing a life vest on board more than a decade ago. But he was dead serious when he made wearing PFDs a mandatory requirement for anyone working on his boat. And he led efforts last year to buy 1,100 of them for local fleet members.

The makers of personal flotation devices are also doing their bit to make PFDs the fisherman’s friend. For decades, no one had gotten around to designing such devices with commercial fishers in mind. Most models chafed at the neck; some had parts that snagged on ropes, or could accidentally inflate with a little too much ease. After consultations with the industry, a range of new designs are snag-free, lightweight and breathable. And they automatically inflate only when they hit the water.

Such improvements are making it easier for fishers like Mr. LeBlanc to convert the once-inconvertible: This year, his fleet planning board, an umbrella group of five organizations that represent 500 fish harvesters in the region, is buying 1,200 immersion suits and 600 emergency radio beacons for members, at a total investment of more than $1.5-million. “We’ve come a hell of a long way – now, it’s not taboo to talk safety,” says Mr. LeBlanc, who is somewhat of an anomaly in wanting more enforcement, mandatory training and labour inspections on boats.

The message is showing early signs that it may be getting through: Fishing fatalities in the province have fallen in the past two years, and Mr. LeBlanc cites several recent cases where personal flotation devices literally saved lives. And, beyond PFDs, there are improvements afoot in Nova Scotia. Some local committees and the Department of Fisheries now won’t open the fishing season if the weather is bad.

Still, says Mr. LeBlanc, “weird things happen” out on the water, where unpredictability is the only constant. Despite his vigilance, he himself has had close calls: He once fell between two boats at the wharf, into icy water; another time, a rope caught on his oilskin and nearly pulled him overboard; and his boat was once slammed by a rogue wave.

Indeed, he has experienced as severe a maritime tragedy as anyone could be expected to endure: When his son Matthew was 5, he was killed in a freak explosion aboard Mr. LeBlanc’s boat, while out in the Chéticamp Harbour.

“I don’t want anybody,” he says, “walking in my shoes.”

With research assistance from Stephanie Chambers.

Tavia Grant is a reporter at The Globe and Mail.