He seldom treats patients, but Howard Platnick still brings in as much as $800,000 a year working as a doctor.

The Toronto practitioner makes his living compiling reports on accident victims for auto-insurance companies. A review of about three dozen of Dr. Platnick's cases by The Globe and Mail shows he usually finds the injuries suffered by claimants aren't significant.

In a good year, Dr. Platnick has said, he gets roughly 1,500 bookings, which suggests he assesses six accident victims in an average workday. Approximately 300 of those are "paper reviews" in which he's sent a person's file and evaluates their condition without ever seeing them.

Dr. Platnick is among a raft of physicians whose reports have been rejected by judges and arbitrators – some repeatedly – for being inaccurate, unfairly biased against the injured person, or written by someone else. And yet those doctors continue to get work.

Case records show Dr. Platnick talked another doctor into altering her report in an insurance company's favour, then had her back-date it to when she wrote her initial assessment. In another instance, he made no mention of two car crashes the victim actually had, but referenced an earlier accident that never happened.

He declared a truck driver could go back to work, after noting the man could no longer handle driving long distances.

Rules governing doctors stipulate any such assessment should be independent and unbiased. However, records show State Farm e-mailed Dr. Platnick last year, thanking him for "co-operating with us" to get a claim settled, saying "your involvement was essential to our efforts."

In Ontario and B.C. alone, hundreds of Canadian doctors take in roughly $240-million a year collectively, putting their names to accident injury assessments for the auto-insurance industry. Insurers primarily use those reports as leverage, to limit or cut what they pay for treatment and other benefits.

Laura Carpenter found out how seriously those practices affect victims, after Dr. Platnick wrote a brief "summary" for her insurance company declaring there was "consensus" among a team of doctors that she was not catastrophically injured. He came to that conclusion without ever meeting her. That is a common, accepted practice among doctors doing these assessments.

TD Insurance ended Dr. Carpenter's coverage, a month after it received Dr. Platnick's summary. A family doctor herself, Dr. Carpenter then went five years without full treatment for her injuries, before she had a chance to show TD – at a long-awaited arbitration hearing – the "consensus" his report cited didn't exist.

"Because I did not receive as much treatment as I needed, I believe that my injuries and impairments worsened significantly," Dr. Carpenter said in an affidavit.

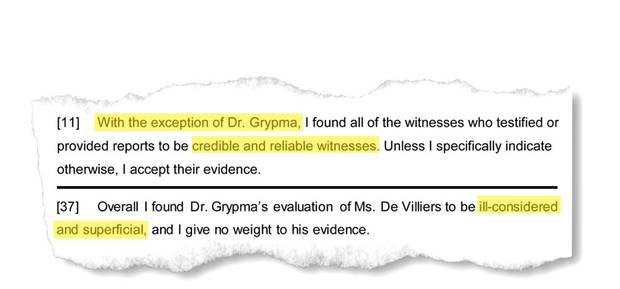

Dr. Platnick was paid though Sibley and Associates, one of several assessment companies that hire the doctors on behalf of insurance firms, then edit and polish the medical reports. Those middlemen take a cut of the fees, which come from premiums paid by drivers.

According to an 85-page report by another doctor on the team that examined her for Sibley, Dr. Carpenter couldn't work or even get around without a walker, had chronic pain all over and was in "constant distress" – from injuries that had been "inadequately treated."

Some days the pain was so bad she sent her children to school in a cab.

Records buried in her files and later obtained by Dr. Carpenter's lawyer include several e-mails from a Sibley administrator to members of the medical team, asking them to remove or alter sections of their assessments. Key changes were then made, some of which watered down or omitted their opinions on how seriously Dr. Carpenter was injured.

Two of the doctors pushed back, however, telling Sibley they would not alter their reports or sign Dr. Platnick's "consensus." One called the pressure to do so "offensive and insulting." Yet, Dr. Platnick's opinion prevailed and was the only one TD heard.

Confronted years later with the missteps in her case, TD quietly settled with Dr. Carpenter. She is now suing Dr. Platnick and others for $7.75-million in Ontario Superior Court of Justice.

In his defence filing, Dr. Platnick said the assessment company that hired him should have taken the term "consensus" out of his summary, when other doctors didn't sign on, before sending it to TD without his knowledge. He also claims the dissenting doctors' assessments didn't fit with Ontario insurance rules.

Dr. Platnick said he finds it "incredible" that an accident victim "turned a minor fender bender into a catastrophic impairment case," calling it "unfair" that she is now suing for millions, despite already receiving a "gratuitous windfall" settlement from TD.

In its statement of defence, Sibley says it had input on the doctor's assessments but claims it didn't change their "substance."

Sibley declined The Globe's request for an interview. Dr. Platnick's lawyer said his client would "be happy to speak" about this, but couldn't for legal reasons. Through her lawyer, Dr.. Carpenter also declined to comment.

Tatiana Nemchin, a former yoga studio owner, suffered from PTSD after an accident, but the psychatrist who examined her told the insurance company that her PTSD wasn’t serious. Ms. Nemchin fought in court, where the psychiatrist was exposed not only for writing things about her that were wrong, but for misrepresenting his credentials. Read more about Ms. Nemchin’s case below.

JACKIE DIVES/THE GLOBE AND MAIL

Edward Tanner, shown in his home in Sarnia, Ont., lost his benefits from insurance company Allstate based on a neurologist’s report. Mr. Tanner fought for five years to have Allstate pay for treatment of his brain injury, and during that time, he says, he got addicted to prescription opioids and also began selling them to pay his bills. Read more about his case below.

CHRISTOPHER KATSAROV/THE GLOBE AND MAIL

The lucrative, little-known growth industry that generates "independent medical evaluations," or IMEs as they are called, has gone largely unchecked in recent years. It is a byproduct of an auto insurance system that even the Insurance Bureau of Canada says is "broken," at least in Ontario.

That became clear in case after case, as the Globe and Mail scoured more than 300 court and arbitration rulings on car accident cases in Ontario and B.C., where most doctors who write those reports are based.

Injury lawyers working on behalf of accident victims also hire IME doctors, to help bolster the claimants' cases, while insurance companies view every claimant but the most seriously injured as a possible exaggerator or fraudster. That starts an expensive, drawn-out game of what the insurance bureau calls "duelling assessments," by numerous doctors, working both sides.

Legitimately injured accident victims caught in the middle are the most profoundly affected, and report being shocked and devastated or at least baffled when doctors for hire conclude they are not seriously hurt. Sometimes their injuries get worse, instead of better, as they go months or years without adequate, goal-oriented treatment. Some get hooked on strong painkillers while being sent to numerous doctors for assessments.

Normally, when doctors treat patients, the law says they owe them a "duty of care." Not so with these assessments. IMEs are done outside those rules, so the doctors are beholden to whoever hires them, not the accident victims they assess.

Injury lawyers say claimants up against unfair or incorrect doctor reports end up feeling intimidated and exhausted, so many of them settle – for less treatment coverage than their own doctors feel they need.

The bureau says even the insurers who use IMEs have "long-standing concerns" over their "impartiality, quality and costs." Questionable practices are so rampant, even the organization representing doctors who do IMEs has cited "arrogance and lack of formal training" as a problem. The Canadian Association of Medical Evaluators has written to members, warning "amateurism, bias and fraud will be tolerated less and less in the future."

The vast majority of cases remain hidden from scrutiny, however, because more than 95 per cent of claimants settle out of court and their files are kept under wraps. Complaints about doctors to their regulators are also not made public. The Globe uncovered several where doctors were criticized or cautioned by the College of Physicians and Surgeons in Ontario for questionable practices, but none has been disciplined.

What Stacey Taylor went through represents the most common and perhaps worst-case scenario: The legitimate, seriously injured accident victim who goes up against seasoned IME doctors working for insurance companies, and who loses and can't comprehend why.

"You don't realize how the system is set up against you until you are in it," she said.

Ms. Taylor doesn't remember the crash in Niagara-on-the-Lake, Ont., that ended life as she knew it. Her car was broadsided, shoving her leg bone into her hip and smashing it beyond repair. That put Ms. Taylor, a federal archeologist, in a wheelchair for months, trying to walk as her hip joint deteriorated.

Pembridge Insurance started sending her to doctors, among them Dr. Platnick, to get assessed, she said, while she was still in hospital.

"These people are trying to prove you are lying – and you know you are not," said Ms. Taylor. "They would try to move my leg until I would scream because the bone was hitting bone."

Her doctor said she was too young for a hip replacement at the time. As painful arthritis and other complications set in, Ms. Taylor fought to recover, exhausting her basic coverage. Pembridge then stopped paying, when she was in the middle of her treatment, because Dr. Platnick – who'd never met her – declared her injuries not serious enough to warrant long-term benefits.

"I just thought, oh my God. I have such obvious injuries. I've worked so hard to get better and then it was just thrown back in my face," Ms. Taylor said. "It's a terribly broken system. There is no accountability for these doctors."

Dr. Platnick had summed up reports from other assessors, also paid by Pembridge, and concluded she was not catastrophically injured – in contrast to her doctors' views. Ms. Taylor's last chance was at arbitration, where she said she limped in, using a cane. Dr. Platnick's report carried the day.

"It would just make you cry because you knew that this was ridiculous and you were in a system that you couldn't beat," she said, while choking back tears.

In his report on Ms. Taylor’s case, the arbitrator upholds Dr. Platnick’s findings that she was not catastrophically injured.

Another doctor on the team paid by Pembridge to assess Ms. Taylor was Lawrie Reznek, an Ontario psychiatrist.

His reports have been rejected by judges and arbitrators in at least 10 cases over the years for "serious flaws," "cherry picking," "impartiality found wanting," "a number of problems," "incorrect" assumptions and "superficial" interviews.

In case after case, Dr. Reznek used what he's admitted are unique, unproven tests on accident victims. He would tell a joke and if they laughed he would report they seemed fine. He'd have his assistant knock on the door and, if the noise didn't startle the person he was interviewing, he would conclude they weren't seriously affected by their accident.

Dr. Reznek often concludes people are "malingering," which essentially means they're faking injuries. In a small minority of court cases, his testimony has helped insurers get dubious claims thrown out, which may explain why the industry continues to hire him as an expert.

He's testified he makes more than $100,000 a year, just assessing auto insurance claimants. In one case this year, he charged $14,000 for a single day in court.

"You have paid insurance for so many years and you trust doctors … but then you see them and you realize they have an agenda," Ms. Taylor said. "You respect them and you listen to their opinion. You don't think they are not going to have your best interests at heart and line their pockets."

Dr. Reznek declined The Globe's request for an interview, but pointed to a recent case where an injury lawyer asked a judge to disqualify him as a witness, because of his history. The judge refused, ruling even though he is "zealous" in defending his opinions, that doesn't prove he's biased.

IME doctors are allowed to testify repeatedly, despite questionable track records, because most Ontario judges won't allow injury lawyers to challenge them about past testimony. Precedent-setting case law says that just because an expert is discredited in one instance doesn't mean he or she won't be credible in another.

Maria Parra is a Toronto realtor who learned the hard way how much power and influence those doctors have, even after they've been criticized numerous times.

"I didn't know what I was getting myself into. But the longer I went, the more I realized – this is a business," Ms. Parra said.

She took her case to trial, she said, because she was in constant pain after being rear-ended and had lost her $200,000 annual income. The other driver's insurance company opted for a jury – as injury lawyers say they usually do – and the verdict left Ms. Parra with nothing.

She believes the jurors were persuaded by doctors, including Toronto physiatrist Rajka Soric, hired by the insurer. (A physiatrist is a physician who specializes in physical medicine and rehab.)

"The fact they succeeded – that totally destroyed me," Ms. Parra said. "The picture they presented to the jury was not me."

Unbeknownst to the jury, Dr. Soric has been taken to task by judges over the years, for misreading an accident victim's medical history, claiming to do tests that were "not documented," testifying about non-existent injuries, making reporting mistakes, "ignoring" her expert duty to be fair and being an "advocate" for insurance companies.

Dr. Soric told The Globe she believes that judicial criticism was simply the result of injury lawyers trying to discredit her, over irrelevant details that made no difference to her opinion. "They are taking things out of context. My reports would say exactly the same thing – even if they didn't find small mistakes, my conclusions would have been the same," she said.

"I really resent the way the expert witnesses are handled. The process is very adversarial. Cross examination does not focus on professional opinion of the witness … instead, they really try to undermine your professional and personal credibility."

Dr. Soric has testified she's made as much as $470,000 a year, most of it from doing IMEs for insurance companies. She said she hasn't done more work for accident victims because injury lawyers almost always decide not to hire her when she doesn't tell them what they want to hear.

"I am asked to give them a call and if they find my report is not in their favour, they will say please don't write a [final] report," Dr. Soric said. "They say: 'Thank you very much but this is not helpful to my case. Please submit an invoice and don't write a report.'"

In Ms. Parra's case, the judge took the unusual step of making a post-verdict ruling that rejected the testimony of the doctors on the insurance side, including Dr. Soric, who had played down the effect of the accident.

The court then declared Ms. Parra's injuries were catastrophic after all, which meant she still got nothing but wasn't stuck with the insurer's legal bills.

"I am still paying, though. I am still suffering. I am still having expenses and I am still struggling with my life," Ms. Parra said

In a 2016 ruling, Ontario Justice John Sproat rules that Ms. Parra suffered a serious injury from her car accident.

Dr. Martin Grypma’s office is in a hangar at the Langley airport in suburban Vancouver, where he keeps a private plane. In the past eight years, he has direct-billed B.C.’s public auto insurer $1.8-million.

JACKIE DIVES/THE GLOBE AND MAIL

Another criticism of doctors who do independent medical evaluations has to do with their credentials, or lack thereof. Accident victims such as Ms. Parra say they've been surprised to find some doctors they are sent to for IMEs haven't treated patients for years.

The Globe obtained physician rosters from those companies that tap doctors to do IMEs across Canada. Hundreds of doctors are listed, and several have been licensed for more than 30 years. Many are at or past retirement age.

One orthopedic surgeon, Martin Grypma, known for getting chastised by judges, gave up his full licence seven years ago. Nine years before that, an Alberta court found him negligent for botching routine back surgery on a patient, leaving her permanently disabled.

His practice is now restricted to conducting IMEs only.

Dr. Grypma works out of a hangar at a suburban Vancouver airport, where he keeps his private plane. Over the past eight years, he billed B.C.'s public auto insurer $1.8-million, which hired him directly, not through a middleman firm. He also earns more, by working for at least three of the assessment companies.

Not only is Dr. Grypma not a fully licensed doctor, his reports have been rejected by the courts more than a dozen times. Judges have called him out for being "deliberately or grossly careless" in one case and "misreading" an accident victim's records in another, while being "argumentative," "incorrect" and "an advocate." Another judge called his evaluation "ill-considered and superficial."

Excerpts from two B.C. Supreme Court rulings in separate cases, in 2016 and 2013 respectively, question the credibility of evidence brought forward by Dr. Grypma.

B.C.'s College of Physicians and Surgeons told The Globe that when a doctor is criticized by a court a "file would be opened for investigation." However, it confirmed none of the IME-related probes it did in the past five years stemmed from court rulings, which would include those involving Dr. Grypma. He declined The Globe's request for an interview.

In Ontario, one neurosurgeon listed on a roster of IME doctors has been a physician since 1954 – 63 years – but is still on call to do IMEs for two assessment companies.

"I think anybody who practices for this long, it's time to retire," Dr. Soric said. "I am not sure that every single one of them is fully qualified to perform these assessments because you have to simply be aware of all the possible medical complications from injuries."

The physician rosters show most of them never meet the people they assess. Those doctors are only available to do "paper reviews" of accident victims' records, which can be sent to them electronically, wherever they are. However, other doctors told The Globe they would never assess a person's injuries without seeing them in person.

In Tatiana Nemchin's case, an Ontario psychiatrist was exposed in court, not only for writing things about her that were wrong, but for misrepresenting his credentials, by giving the impression he had a full-time practice, when he didn't.

"It was shocking, finding out basically his whole practice is doing this for insurance companies," said Ms. Nemchin, a former yoga studio owner, who added the reports had "inaccuracies and quotes of words I never use in my life [in his report]. The first thing is disbelief. You are like, what? And then you think, is this the right file?"

Richard Hershberg has been a psychiatrist for 36 years. He met Ms. Nemchin once and then reported to the insurance company her PTSD from the accident couldn't be that bad, because she was able to move to B.C. from Ontario to live on her own.

Two years after writing that, he conceded in court she had never moved out west and he actually "didn't nail it down," along with other mistakes and omissions. The CV he put into evidence stated he was a "senior psychiatrist" at a local clinic. In court, he admitted that was inaccurate and that he earned 90 per cent of his income – at $600 an hour – doing IMEs.

If Ms. Nemchin hadn't taken her case all the way to court, none of that would have been discovered.

Dr. Hershberg said his mistakes had no bearing on his opinion of Ms. Nemchin's condition. "Those are basic mistakes. I am sitting here now, I have nine binders for a case. Often, it's not a case of not getting enough information; it's having a lot of information to go through," he told The Globe.

He said he often finds accident victims' aches and pains are made worse by aging or other problems, then prolonged when they don't get back on their feet.

"It's not fraud. It's people in their own way that are suffering," he said. "They are struggling with life – not so much as with pain."

Ms. Nemchin said her biggest struggle was having to go to trial, which she described as an exhausting ordeal no one should have to endure. "It was hell sometimes … I can totally understand why people give up because your integrity is questioned. Everything you do is questioned. The story of your life becomes not what it is," she said.

"You just never get time for your nervous system to stop and heal. The process the insurance company puts you through makes your stress worse … you pay for insurance and it shouldn't be that difficult."

Only the colleges that license doctors have the power and mandate to hold them accountable. Those regulators all have set standards, which stipulate doctors should be accurate and unbiased when they write IMEs.

Despite regular criticism in the courts and complaints "every year" from accident victims, the Ontario College of Physicians and Surgeons said it couldn't find one doctor in the past five years who has been formally disciplined.

In B.C., the College said it has concluded 26 IME-related investigations since 2012 but only one doctor received "low level criticism."

The Globe found eight instances where Ontario doctors have been quietly advised or cautioned, however, over inaccurate or inappropriate reports. That criticism is not posted on the doctors' online history, so if anyone checks their college records they will find nothing.

Neurologist Luis Morillo, who is only allowed to teach, was caught doing insurance assessments without a licence.

Occupational medicine specialist Katherine Isles was "cautioned" for writing an "inadequate and inaccurate report." The College said Dr. Isles disregarded how serious an accident was and got basic details wrong, which was "indicative of the absence of almost any factual content."

Psychiatrist Leslie Kiraly was advised to stop calling his assistant "doctor," because he had him do a psychiatric evaluation on an accident victim, after introducing him as a physician.

Only unlicenced Dr. Morillo was told to stop doing IMEs, while the others carried on without the public knowing they'd been criticized.

Some have faced more than one College complaint, such as physiatrist Alborz Oshidari, who has been investigated at least four times. Another doctor reported him to the regulator a decade ago, after finding errors in Dr. Oshidari's assessment of his injuries, from an accident he said he was lucky to have survived.

"I was fortunate enough to be a doctor and recognize his unfair examination and the College saw it my way," said Ontario general practitioner Michael Madonik.

"I took time out of my life and my practice to say, 'if you are going to beat me up I'm going to do something about it.' People have to take the time to stand up for themselves. But – I was in a better position than most."

Four years later, Lynn Logtenberg complained about Dr. Oshidari, for concluding she was not catastrophically injured, even after she called him out for misreading medical reports and misquoting her doctors. The College told Dr. Oshidari to be more accurate in the future, but that didn't help Ms. Logtenberg, who was still left fighting her insurance company for benefits.

Godwin Jogarajah filed his case just last year, after he had to push Dr. Oshidari to correct several mistakes in a report about his injuries. The College took no action. In the fourth case, the College found the physiatrist left out details about an accident victim's condition, but didn't criticize him for it.

Dr. Oshidari's opinion has been disregarded by arbitrators in at least four other insurance cases, some because he never saw the claimants.

In one case, he concluded a 58-year-old man who spent months in a wheelchair was not seriously injured, because he didn't need surgery. The only reason the man didn't need surgery, though, was because no operation could fix his injury.

Dr. Madonik doesn't understand why insurers keep relying on those reports. "To repeatedly go to these doctors when they have been discredited, there is something wrong with that. It's almost played like a game but it shouldn't be a game."

Dr. Oshidari declined the Globe's request for an interview.

‘They dragged it out and it drove me crazy – and so I was doing stupid stuff,’ Edward Tanner says of his battle to get treatment for a brain injury. ‘I was on medication and I was losing my mind.’

CHRISTOPHER KATSAROV/THE GLOBE AND MAIL

Some legitimately injured accident victims suffer and deteriorate for years without money for proper treatment, while insurers send them to a merry-go-round of doctors, all well paid to keep challenging them on whether they are really injured. Many turn to opioid painkillers.

The Globe found several cases where people were made to see more than a dozen physicians. If they refuse to go, even when they are feeling too ill, the insurance company can close their file. Doctors and assessment companies also charge insurers or accident victims as much as $6,000 for any missed or cancelled appointment.

One judge noted an accident victim had been sent for at least 17 medical assessments by a "small army" of doctors, including five neurologists and four neuropsychologists. The court ruled sending her to any more would be "oppressive" and a "fishing expedition."

Edward Tanner suffered through five years of countless appointments, which the arbitrator called a "deplorable amount of time," before he won a fight against Allstate Corp. to pay for treatment.

In those years that he struggled with no income and a brain injury, Mr. Tanner said he got hooked on prescription opioids, which he also sold on the street to pay the bills.

"They dragged it out and it drove me crazy – and so I was doing stupid stuff. I was on medication and I was losing my mind," said Mr. Tanner, a former carpet installer. "My wife left me. I lost money. I borrowed money and it put me in the hole. Yeah, I sold some of my pills – to survive."

Allstate had cut him off years earlier, based on a report by Adrian Upton, who has been a neurologist for 43 years.

"I was really upset when I was in his office," said Mr. Tanner of Sarnia, Ont. "I remember him saying to me, 'You don't have a head injury. You can go back to work. You can do whatever you want in life.'"

Another accident victim, who was cut off based on Dr. Upton's assessment, fought his insurance company for six years, before an arbitrator ruled in his favour. By then, though, he was in a deep depression and it was too late to salvage his music studies.

Dr. Upton has been investigated by the Ontario College at least once, for allegedly misquoting medical records, but he faced no repercussions. An appeal board sent the case back for re-investigation this year, however, because College investigators failed to look at the records, to actually check if Dr. Upton had quoted them incorrectly.

Arbitrators have questioned or rejected Dr Upton's opinion a handful of times, going back 30 years, but he's also helped insurers win tough cases. One woman with a dubious brain injury claim fought eleven years for benefits, before Dr. Upton's report helped the insurer get her case thrown out.

Dr. Upton's office didn't respond to requests by The Globe for an interview with him.

It's not simply insurance companies who are working closely with IME doctors. The other side to all of this, according to insurers and physicians who work for them, is that injury lawyers also hire IME doctors who bolster or exaggerate their clients' cases, resulting in the phenomenon of "duelling assessments."

For example, court records show Allstate hired both Dr. Hershberg and Dr. Reznek to fight a questionable injury claim from a bagel maker, after the man hired a lawyer and "manufactured" his symptoms to get a payout because his bakery had gone out business.

The baker suddenly tapped Allstate for benefits three years after his car accident, while he was being chased for back taxes and facing charges for trafficking in marijuana. He claimed the accident made him mentally ill for life.

Psychiatrist Mortimer Mamelak, hired by the baker's lawyer, said he had "motor vehicle accident injury syndrome," which is not a recognized condition. Dr. Hershberg and Dr. Reznek testified he had no diagnosable disorder and the arbitrator believed them, so Allstate was able to close the file.

Ontario insurers have "long been concerned that assessments could be used to inflate claims for bargaining purposes," said Insurance Bureau of Canada spokesman Andrew McGrath.

"Going back more than a decade, the insurance industry has called for a serious examination of the effectiveness of existing structures," he said.

All drivers are getting hit with the huge price tag.

In Ontario, with the highest auto insurance premiums in Canada, medical assessments ordered by insurance companies eat up approximately $200-million annually, paid to doctors and assessment companies. And that's just one province.

"I think the public is in the dark. Like I was. I would have never known this unless I went through this accident," said Ms. Parra, the injured Toronto realtor. "They made their money and they are still making money, because of other people's suffering."

Kathy Tomlinson is an investigative reporter in The Globe and Mail's Vancouver bureau. ktomlinson@globeandmail.com

HEALTH IN CANADA: MORE FROM THE GLOBE'S KATHY TOMLINSON