They found him late in the morning on eviction day, firefighters first glimpsing his body through the rear window of his green tent. It was raining and he

was alone.

The date was Oct. 15, 2014, a dreary Wednesday three months into a protest at Oppenheimer Park. The demonstration, staged in the heart of Vancouver's impoverished Downtown Eastside, had begun as a makeshift encampment for a few homeless people and grown into a politically charged "tent city" – a hundreds-strong denunciation of the city's lack of affordable housing.

Vancouver officials, citing health and safety concerns, eventually decided the situation had become untenable and a judge agreed, ordering the campers to vacate the park. Some had started packing up, but many tents still remained when the firefighters, conducting a wellness check, found the body at about 11 a.m. Paramedics arrived a short time later and pronounced the man dead. Police did not suspect foul play, but they put up yellow tape and took

photos to document the scene. A few people crowded around to see what

was happening.

The man had died the day before. No one had noticed.

Police cover the tent where Joerg Brylla’s body was found.

JOHN LEHMANN/THE GLOBE AND MAIL

The BC Coroners Service and Vancouver police searched for his next-of-kin for nearly a month but found no one – an exceptionally rare occurrence. Meanwhile, his body was stored in a morgue at Vancouver General Hospital, awaiting relatives who never came. Finally, on Nov. 7, 2014, authorities revealed his identity to the public: Joerg Brylla, 69, of no fixed address.

"He was known to friends in his community as Bunny George," a news

release stated.

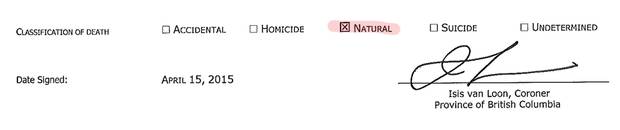

From the B.C. coroner’s report into Mr. Brylla’s death.

( Read the full coroner's report on Mr. Brylla's death)

At least 281 homeless people died in British Columbia between 2006 and 2013, though the actual figure is likely much higher, according to the coroners service. They were largely men in their 40s, and about half of them died accidentally. At nearly 70, Mr. Brylla was an exception – and an

unsettling mystery.

What was this older man doing at a protest dominated by younger people? Who was he and what happened in his seven decades to lead to this stark, doleful end? Someone's son, someone's friend, perhaps someone's spouse – how did he fall out of the mainstream, off the grid, and die there in the park, at once surrounded by people and completely alone?

Over the year since his death, The Globe and Mail has attempted to uncover Mr. Brylla's story. He was not a public figure, so an online search yielded little. The leads came slowly, the pieces of the puzzle often elusive. The Globe located family members, friends and acquaintances, conducting dozens of interviews in three countries, two provinces and two U.S. states; it also reviewed his court and academic records, municipal files, yearbooks and genealogy websites. The picture grew clearer and continued to evolve – just before the planned publication of this story two weeks ago, the arrival of a new batch of documents added new revelations. Even then, inevitably, so much remains unknown.

It turns out Mr. Brylla was born in a devastated Germany just after the Second World War ended, emigrated to Canada with his parents, lived in Ontario and then California. He'd been an avid surfer and a U.S. Air Force enlistee, spent time in prison and time on the street. His journey was made more difficult by mental-health issues; he could be self-destructive and violent, but also gentle and compassionate – particularly to the wild rabbits he caught and cared for and that, more than any other pursuit or group of humans, became part of his persona.

This is the story of Bunny George.

‘I think he cared more for the bunnies than he did for himself. But the bunnies kept him alive’

0:45

'I had lost a friend'

Of a few hundred people remaining in the park the morning they found Mr. Brylla, not one approached authorities with information about him. Not that day, not ever, according to a Vancouver Police spokesman.

Globe reporters asked around. They popped into social-service providers, community centres and medical facilities on the Downtown Eastside, inquiring if anyone knew the man who died at Oppenheimer Park. Finally, a woman at a food bank scrawled a phone number on a piece of paper – that of Kim Monteith, an employee of the B.C. SPCA.

Kim Monteith, an employee of the B.C. SPCA, had known Mr. Brylla for nearly a decade before his death.

HANDOUT

Ms. Monteith would become the first major lead into the mystery of Mr. Brylla's life, sharing her memories with The Globe over several interviews. She had met him nearly a decade earlier, in the late summer of 2006. On that day, she recalled, she was in an alley in Vancouver's West End, trying to free a pigeon that had become ensnared in netting. Then in his late 50s, Mr. Brylla wore a light, red-and-black sweater with pale grey slacks. He pushed a cart piled high with cardboard boxes, a blue suitcase and a green pet carrier, all draped in a bed sheet and a tarp. A length of chain woven throughout his possessions offered a bit of security.

"He was pushing this cart around, with this crate," Ms. Monteith said. "As I was trying to get access to this pigeon, I started talking to him. He said, 'I've got a bunny in here,' and I'm like, 'Sure, sure.' I went and looked, and sure enough, he did."

That was the beginning of a friendship. Ms. Monteith, now manager of animal welfare for the society's B.C. chapter, often works with the homeless, connecting them and their pets with Vancouver-area social-service providers. Over the years, she and Mr. Brylla regularly met for coffee and he would tell her about his rabbits. She helped supply him with rabbit pellets and hay and, when necessary, arranged veterinary care using funds from a B.C. SPCA-run

pet food bank.

Ms. Monteith initially saw Mr. Brylla with only one rabbit, but in subsequent encounters he would have up to 10 at a time. He named each of them – Howard, Speedo, Fuzzy Butt – and insisted he knew their personalities,

she said.

She learned of his death through a Facebook message from another animal-rescue worker.

"I felt regret that I hadn't gone out and looked for him again [recently]," she said. "I was out in the park at night [during the protest] and it was too dark to find him, or talk to people there, and it was days before I found out. I felt I had lost a friend, for sure."

No town called Barkhausen

Other clues gradually emerged. A classmates website showed that Joerg Brylla had graduated from Central Secondary School in Hamilton, Ont., in 1964; a visit to that city was in the offing. A search of the online criminal-record file of the B.C. Justice Ministry placed him in the province as early 2003, when he was charged with uttering threats against a woman after the theft of her purse.

In early December, a memorial service was held in East Vancouver, where among the 20 people in attendance was Ellen Silvergieter, a church advocacy director who had helped Mr. Brylla sort out paperwork for social assistance. "He came from Germany as a young child with his parents," she said. And so the search turned to Mr. Brylla's beginnings.

By the time the newspaper began its German reporting in earnest, it had acquired a few more scraps of information, all of it problematic. The first challenge was timing: Joerg Brylla was born on Aug. 27, 1945, three months after the surrender of Nazi Germany; it was unclear how many documents from that time would be preserved. Also, on a Canadian immigration form,

his birthplace was listed as "Barkhausen, West Germany," but such a town

no longer exists.

Eventually, an archivist turned up the fact that his mother, Klara, was living in temporary housing for people displaced by the war when her son was born. The housing was in what is now the town of Minden, though the birth took place in nearby Barkhausen, which is now part of a larger town.

City archives, military records and genealogy websites helped flesh out the story. His father Rudolf was a Berlin butcher posted to a unit within the German armed forces who spent at least two years in Paris, eventually becoming a corporal. Klara ran her own delicatessen and grocery store,

later becoming a nurse.

Three weeks after she arrived in Minden, U.S. forces carried out the last of a series of devastating bombing raids, all but obliterating the town's centre. Then, on April 1, the town was occupied by the 1st Canadian Airborne Battalion and became part of the British-occupied zone of Germany when

the war officially ended in May. After Joerg Brylla was born, he and his mother stayed in Minden until November, 1946, when they returned to Berlin, a wreck of a city struggling to rebuild.

Berlin’s Potsdamer Platz is shown in an archival photo.

By the early 1950s, Rudolf and Klara were looking to leave Germany. They were not alone: Some Germans were weary of the adversities of postwar life, and some wanted to reject everything the country stood for. Still others feared a new conflict with the Russians.

Around the same time, the United States and Canada flung open their doors to German immigrants. Between 1951 and 1960, 580,000 Germans immigrated to the U.S. Another 250,000 went to Canada during the same period. Among them were Rudolf and Klara Brylla – then pregnant with their second child – and their six-year-old son Joerg.

In 1952, the Bryllas crossed the Atlantic Ocean aboard the Greek Line ship the Columbia, arriving in Halifax. They then travelled by train to their final destination in Canada – Hamilton. In November of that year, Klara gave birth to a girl they named Janette.

Fourth row, Grade 9

Hamilton in 1952 was a bustling port city on the edge of Lake Ontario, its dynamic economy a magnet for thousands of immigrants from across Europe. For the Bryllas, moving there represented the next step in a journey toward a more prosperous life.

Today, most of the tangible evidence they were ever in the city is contained in the archives of the Hamilton Public Library and the district school board. The family home in the city's east end has been torn down; an elementary school stands on the spot. The high school Mr. Brylla attended is gone, as is the meat-processing plant where his father worked.

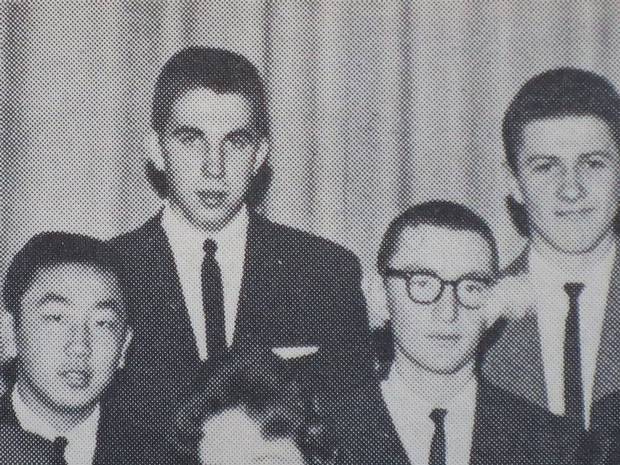

Mr. Brylla first shows up in Grades 9 and 10 at Central Secondary School, a shadowy figure in the fourth row of the 9A class as pictured in a yearbook photo. The lower half of his face is concealed by the head of a student standing in the third row. Mr. Brylla is listed as Yogi, not Joergi.

A school-board archivist noticed that his home-room teacher that first year was Ted Lewis, who still lived in Hamilton and agreed to an interview. Back then, Mr. Lewis was a 24-year-old embarking on a teaching career that would last until he retired in the 1990s. Now nearly 80, he examined the yearbook photo of Mr. Brylla and struggled to remember him. He found that odd because the other students linger in his memory.

"What that says is [Mr. Brylla] was never a troublemaker," Mr. Lewis said. "He was never a problem, but he also was not one of the outgoing, better students in the class. He may have been a quiet one who kept to himself."

In a Grade 11 yearbook photo, Mr. Brylla – now called "Gogi Brylla" – is far more visible than in the Grade 9 image. He stands among three students in

the fourth row wearing a suit and tie. But that same year, he was scratched

off attendance records in September, according to the archives. Central Secondary School no longer exists.

Mr. Brylla is shown second from left in a Grade 11 high-school yearbook photo.

HANDOUT

Hamilton's city directory lists Mr. Brylla's father Rudolf as a labourer at Essex Packers in 1952. Eventually he was listed as a "formn" – presumably a foreman. Back then, Essex was a thriving operation, but financial difficulties forced its closure in the 1970s. Rudolph Brylla shows up with his foreman title in directories for subsequent years through to 1963, the family's last year in Hamilton.

An immigration form the family filled out for entry to Canada records their Hamilton contact as "Reizgys." There were four Reizgys listed in the Hamilton area; one of them turned out to be the son of the man in question.

In an interview, George Reizgys vaguely remembered the Bryllas as his parents' friends. He suspects the Bryllas needed a sponsor to emigrate from Germany. "Most likely, that's how my father's name came up: as a sponsor," he said

at a downtown coffee shop. Mr. Reizgys's elderly father has no memory

of the Bryllas.

The younger Mr. Reizgys recalled a high-school talent show in which Mr. Brylla played the accordion. He also has fleeting memories of the two playing baseball together.

In 1963, the Bryllas moved once more. Mr. Reizgys recalls seeing them off to California: "I remember they had a big station wagon, all loaded up."

The Bryllas settled in Lake Forest, a conservative community then called El Toro, located about 75 kilometres southeast of Los Angeles, moving into a modest, two-bedroom townhouse. The stuccoed complex in a quiet, residential area remains there today.

Mr. Brylla, then in Grade 12, is shown in a group yearbook photo from Laguna Beach High School.

HANDOUT

'We started dating'

In 1964, Mr. Brylla started attending Laguna Beach High School, a public school located in a famously artistic Orange County community. The school's teams were then called the Artists and their insignia was a paint pallet with brushes, encircled by colourful swatches in rainbow hues.

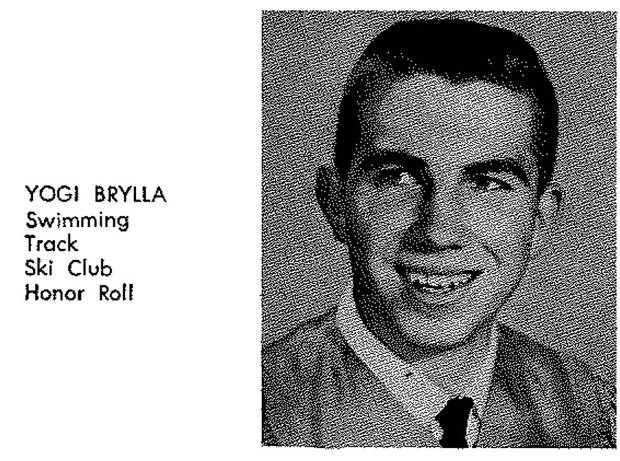

Mr. Brylla, a tall, intense-looking senior with a dark crew cut, participated in swimming, track and the ski club, yearbooks reveal. He also made the honour roll. After classes, he worked part-time as a grocery-store clerk, though he much preferred surfing.

Joerg Brylla in a 1964 yearbook photo.

HANDOUT

That year he met Nancy, an attractive, wide-eyed teenager with a bright smile and big, tidy curls worn close to her head. A year younger than Mr. Brylla but in the same grade, Nancy – who asked that her last name not be used – was part of five high-school clubs, including Medical Explorers and Science Explorers.

Nancy would become the key contact in California for this story. An archivist in Hamilton had turned up genealogy records revealing her brief marriage

to Mr. Brylla, and later her remarriage to another man. A call to the second husband's home in the town of Wildomar led to Nancy, who spoke at

length about her "first love," a man she remembered fondly despite the

passing decades.

"He just kind of came up to me and we started dating – just a typical high-school relationship," Nancy said, conceding she had occasionally wondered what her former flame had been up to. "It was probably the prom or something. He took me out to dinner and we went to a dance."

Nancy – who refers to him as Yogi – recalls her high-school sweetheart as intelligent and "a very gentle soul." His parents were warm and, over family dinners, Mr. Brylla's mother would tell animated stories of their time in post-war Germany, Nancy recalled. She quickly fell in love with Yogi Brylla.

After graduation, he enlisted in the U.S. Air Force – an option that some draft-age men at the time viewed, along with the Navy, as preferable to possible conscription into the Army or Marines. As an Airman basic, the lowest enlisted rank, Mr. Brylla learned about aircraft electrical repair, according to records from the U.S. National Archives. Nancy visited him often at the Luke Air Force Base in Glendale, Ariz., where he was stationed.

In early 1966, Nancy learned she was pregnant. The two hastily married and Nancy gave birth to a baby boy that September.

But there would be no happily-ever-after. For all his charms, Mr. Brylla had his faults: Despite doing well in school, he struggled to hold a job; while Nancy worked three of them, Mr. Brylla spent his days surfing or riding his motorcycle. The credit union froze his account.

"He loved me, but he was so immature that he was dating other women and stuff," Nancy said.

For her, the highs of a first love soon faded. She wanted more for their child – namely, a two-parent family and a sense of stability. The two gave their newborn son up for adoption. "We just weren't ready to take on the responsibility of marriage and family," said Nancy, who today is more than four decades into a happy second marriage and a proud grandmother.

In January, 1967, less than a year into what was supposed to be a four-year enlistment, Mr. Brylla received an honourable discharge from the Air Force. The reasons are unclear. Mr. Brylla's cousin, Erika – found through genealogy records – believes it was due to his flat feet. Nancy says it was because of mental-health issues.

Mr. Brylla's mental-health problems did become more pronounced around this time. Various psychiatric reports, as well as his sister, Janette, would later say that he suffered from either paranoid schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder. Much of his 20s was spent on Southern California beaches, surfing and living what friends described as a "beach-bum" lifestyle.

In the fall of 1968, Nancy filed for an annulment. Mr. Brylla did not contest it.

His cousin Erika remembered him as somewhat of a black sheep who never seemed particularly driven by work or family. "I was around 15 years old [when] Yogi's family moved to Laguna Beach and my family moved nearby," she wrote from Laguna Woods, Calif. "Yogi's favourite thing was surfing and the only job he ever had was a bagger at a local grocery store in Laguna Beach." On surfing, she added: "That's ALL he did." She also said her cousin "passed bad [cheques] and tried to set a local bank on fire."

Sorelle Saidman, a Vancouver woman who would become a friend and landlord of Mr. Brylla's later in life, believed the onset of his mental illness – she believes schizophrenia – in his early 20s was the reason for his withdrawal from his family in California.

"He moved out into his car, and that kind of thing," Ms. Saidman said. "He talked about living in his car quite a bit. His dream was to get an RV and live out of that. 'Bum' is a really good word; he was just bumming around. He was never very industrious."

Mr. Brylla's sister, who died in 2006, grew to resent him for his failures; when their mother grew ill, Janette was convinced it was because she was worried sick about him, Nancy said.

"Yogi was his mother's shining star," his former wife said. "Janette was very bright and intelligent, and a wonderful child too, but Yogi was her baby. So she blamed Yogi for her mother's death."

Upon learning of Mr. Brylla's descent into homelessness, from conversations over the course of several months, Nancy no longer wished to speak for this story. In a final e-mail to a reporter, she wrote that she was glad to know that, in death, her former partner "is more than likely in a better place and not seemingly very tormented any longer."

Robert Yohr browses through photos of his father.

THE GLOBE AND MAIL

A son searches for his father

The first images Robert Yohr ever saw of his father were of the man's lifeless body being carried out of the Vancouver park, a grey sheet draped over the stretcher, police tape around the perimeter.

Mr. Yohr, a real-estate broker living in northeastern Kansas, had typed his father's name into a search engine – something he had done many times before without yielding noteworthy results. But this day was different: There were news articles about him, and video clips of his body being discovered at

a park up in Canada.

"I was sitting there in a surreal state," recalled Mr. Yohr, 49, in an interview

at his Kansas office. Nancy had provided Robert's name and an e-mail had established contact. "It was not the way I had envisioned, all these years, finding out about him."

Leaning back on an office couch, he studied a handful of photos provided by the reporter – the first images he had seen of his biological father alive, with the exception of a small, low-quality yearbook photo. He turned to his wife: "Now I know why they said I look like him."

Mr. Brylla and his son, Robert Yohr.

HANDOUT/THE GLOBE AND MAIL

Father and son both have long, rectangular faces, bright eyes and dark hair. As Mr. Yohr flipped through the photos, his thoughts turned to his own four children, and he inspected for similarities between them and their grandfather.

"Interesting," he said quietly, adding: "He's got a lot more hair on his arms than I ever did. A lot more."

In Olathe, a large, fast-growing suburban city peppered with strip malls and big-box stores, Mr. Yohr and his wife have made a comfortable living as co-owners of a real-estate company servicing the Greater Kansas City area. He first reached out to Nancy in the year 2000, following the death of his adoptive mother, wanting his children to get a fuller picture of their family history. Working off a lone court document, Mr. Yohr began searching, eventually finding her in California.

The two quickly developed a relationship, with Mr. Yohr saying that Nancy and her family have been "extremely good" to him. Nancy told her son a

little about his biological father, though information was limited and he

never pressed on.

"I was pretty satisfied, to be honest, once I had found Nancy and I was able

to develop that relationship with her and her family. That was kind of good enough for me," he said. "However, I'm very inquisitive. I like information, data." He wondered about Mr. Brylla's medical history, his appearance, his interests. Over the years, Mr. Yohr periodically searched online, parsing the

few relevant results.

A few years back, one search result on a genealogy website listed a convalescent home in North Hollywood as a residence of Mr. Brylla's in 1996. The facility itself and its address in what Mr. Yohr knew to be a rough-and-tumble neighbourhood bolstered his suspicions that his father had lived a hard life. There was also the curious warning from Mr. Brylla's sister, Janette, when Nancy reached out to her shortly after meeting Mr. Yohr in 2000.

"She didn't want to meet me, she didn't want to give out any information – just kind of shut down," Mr. Yohr said. "What I remember, most specifically, was: 'You don't want to know him; he's not a good person.' That's what she told Nancy and that's what Nancy told me she said. I always thought it might be cool [to find him], but if he had issues, I didn't want my finding him to cause problems for other people."

Recalled Nancy: "His sister told me, "You don't want to know him. He's homeless and stalking women and all this stuff.'"

'Let's get married in Mexico'

Mr. Brylla continued his educational pursuits throughout his 20s, taking various music courses at Orange Coast College between 1964 and 1972, but never graduating. Meanwhile, the grip of his mental illness grew stronger; court records show he was hospitalized on at least five occasions and had been prescribed medication for his condition.

An address listed for him during this time was for a post office box in Canoga Park, a working-class L.A. neighbourhood that has long grappled with gangs and homelessness.

Handwritten journal entries produced years later, and released along with court documents, help fill in the blanks of this period. In one, Mr. Brylla

writes that he "spent 10 years living in and out of a luxury trailer." In

another, he says he collected Social Security cheques for a serious back

injury sustained while working as a grocery-store clerk.

But perhaps most notable are the few short references in court documents and genealogy records to two past marriages and two sons. Further research would reveal that a third partner of about a decade, a woman named Teresita Binoya, was the mother of his second son, Brian Binoya. Mr. Binoya would be 33 years old today – and an unknown half-brother to Mr. Yohr.

A search of public records eventually turned up the address for a mobile

home community in Palmdale, Calif., linked to both mother and son. The mother, reached by phone, was at first reluctant to talk, but eventually

agreed to an interview at her sister's house in Lemoore, Calif., where she

was spending the holidays.

At 72, Teresita Binoya – better known as Tess – stands just over five feet tall and wears her grey hair short and straight. She speaks with an accent – her mother tongue is Tagalog – and has a ready laugh.

Teresita Binoya believes Mr. Brylla would have been ‘flattered’ by this story: ‘At last, somebody paid attention. Somebody is interested in his life.’

JOHN LEHMANN/THE GLOBE AND MAIL

Ms. Binoya met Mr. Brylla in early 1980, just months after she arrived in the U.S. from the Philippines. She was at a bus stop in Canoga Park, heading to work, when a handsome man with bright blue eyes approached her.

"He said, 'You're Filipino. My first wife was Filipino,'" she said, recounting the first lie he ever told her. "I had just come to America and this white, blue-eyed guy said, 'I had a Filipino wife.' I was kind of impressed."

He introduced himself as Jerry, a composer who scored movies and drove a Cadillac – all lies as well. He got her phone number and called within days. Ms. Binoya soon learned most of his stories were "BS," but no matter. He was entertaining and could "charm a bird off a tree," she said, laughing.

The two briefly stayed together in a Canoga Park apartment, but soon moved into a trailer that Mr. Brylla had bought and travelled the state, camping out primarily in Malibu or Laguna Beach. Then in his mid-30s, Mr. Brylla no longer surfed but still gravitated toward California beach culture.

He talked a lot, prodding his girlfriend to keep up. "Come on, Tess. Talk more!" he would complain. "You're draining all my energy." He spoke often of his various ideas for inventions – all so silly that Ms. Binoya can't remember a single one. "This is all pie-in-the-sky talk," Ms. Binoya remembered his mother Klara saying. "If you're so smart, why are you so poor?"

One day, Mr. Brylla turned to Ms. Binoya: "Let's get married in Mexico. That's where Elizabeth Taylor and Richard Burton got married." (An online search mid-interview revealed that the celebrity couple, who married twice, did so in Canada and Botswana – though they did spend much time in Mexico. "You see!" Ms. Binoya said.)

The couple took the trailer south and married in Tijuana. Brian was born months later, in the spring of 1982. Ms. Binoya described Mr. Brylla as an attentive father who cared for their son when she was at work and "even changed his diapers."

In the ensuing years the couple continued to beach-hop, their travels financed by Mr. Brylla's Social Security cheques and Ms. Binoya's modest income as an accounting clerk. For fun, Mr. Brylla would play the accordion – the same instrument he played in high-school talent shows – at various restaurants, free of charge. Among his standards:

Beyond the Sea and The Last Farewell.

He also collected rabbits, and the trailer became so crowded that Ms. Binoya lost count. "He started with two, and then suddenly there were five, and then six, and then a trailer full of them," she said, in language nearly identical to that used by friends in Vancouver decades later. "He had the names for each of them: 'This is Benji, this is Lancaster.'"

Meanwhile, Brian would often stay at Ms. Binoya's parents' home, affording him a sense of stability and permanence that his mother missed. The nomadic lifestyle had grown tiresome, and Ms. Binoya neither swam nor liked the sun. Other issues emerged as well. "I was thinking maybe he had a split personality or something, because one time he's gentle and then he becomes mean – his temper," she said. "Can't live like that."

Ms. Binoya left her husband in 1990. There were some phone calls in the years afterward, but the relationship eventually fizzled. Their son, Brian Binoya, works for the post office in Santa Clarita, Calif. Ms. Binoya has half-jokingly prodded him to date a woman with blue eyes, in hopes of resurrecting the recessive gene that caught her attention some 35 years earlier. The Globe

did not speak with him – his mother wanted some time to notify him of

his father's death.

When asked why she ultimately agreed to speak for this story, Ms. Binoya paused. "I thought he would like it," she said finally. "George would be flattered. He wanted to be a writer himself, and write about himself. At last, somebody paid attention. Somebody is interested in his life."

'I'm going to kill you'

Public records show that Mr. Brylla had at least two brushes with the law by this point. In 1973, he was found with a hypodermic needle and fined $50; Mr. Brylla claimed he was working as an orderly at various hospitals and happened to have an unused needle on his person following a shift. In 1990, he was accused of striking a woman on the nose; according to court documents, Mr. Brylla insisted "nothing happened."

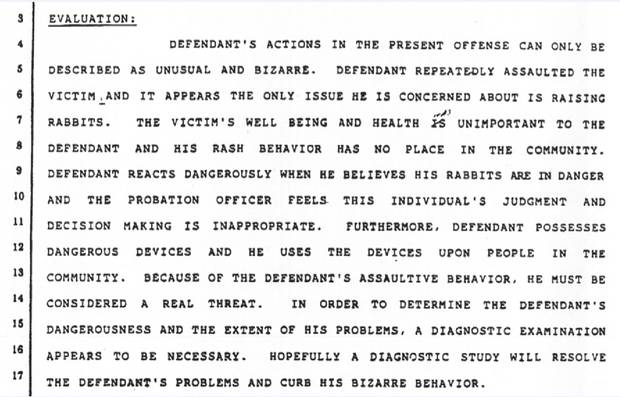

But it was in 1998 that he set off a string of criminal actions that would dramatically change his life. Over several days that March, Mr. Brylla

was accused of a number of offences against his female roommate,

including threatening her with a hammer and saying, "You're history.

I'm going to kill you."

California court documents detail the rest of the alarming encounter: "BRYLLA sprayed his roommate with pepper spray for approximately two minutes. BRYLLA pointed a stun gun at his roommate and discharged it. BRYLLA then followed her around the room for about an hour."

Separate court documents state that Mr. Brylla felt that the woman was endangering his rabbits, in part because of the chemicals she was using to clean the kitchen.

Mr. Brylla was convicted of assault with a deadly weapon and sentenced that October to a term in state prison. Upon parole in February, he was deported to Canada and travelled to Vancouver.

A probation officer’s report in 1998 from the Superior Court of California, County of Los Angeles, notes Mr. Brylla’s ‘unusual and bizarre’ behaviour.

HANDOUT

Despite the change of scenery, Mr. Brylla's U.S. incarceration continued to eat at him. He would often tell acquaintances in Vancouver of grave injustices inflicted upon him in California, but never provided details. The partial anecdotes were often dismissed as the quirky ramblings of an older man

with a penchant for telling stories. No one much wanted to listen.

"Sometimes George's talk about injustice and the U.S. was such that people would ask him to just stop," said Rev. Bob Swann of the First Baptist United Church, where Mr. Brylla at took shelter in 1999 and the early 2000s. "You'd have to go, 'George. Stop. We've heard about the U.S. enough. We've heard about the injustice. We can't do anything about it.' We would try for details, suggesting there had to be a newspaper article somewhere, but nothing was substantiated."

On the morning of March 28, 1999, Mr. Brylla's anger bubbled over. From Vancouver, he called Daryne Nicole, the Van Nuys, Calif.-based deputy

public defender assigned as his defence counsel the year earlier. In two messages left on her voicemail, Mr. Brylla – identifying himself as "Mark

from Tahiti" – threatened to kill several people he deemed responsible for

his earlier conviction: a Los Angeles County Superior Court judge, a deputy district attorney (DDA), a district attorney and two other women who

helped prosecute him.

The DDA, he warned, better set aside the conviction "or every move he

makes will be watched" and his car bombed, according to court transcripts. Meanwhile, the caller said that if the judge didn't set aside the conviction,

the caller would "set aside his life." The messages were "no threat," but a "guarantee," according to the transcripts.

Ms. Nicole called police. Threatening a government official in the U.S. is a felony; a bench warrant was issued and Mr. Brylla was brought back to the U.S. to face a judge. Louis Perez, a special FBI agent assigned to the case, contacted Janette Harris, who listened to the voicemails and confirmed the caller was her brother.

"Ms. Harris said that her brother was diagnosed by a psychiatrist as a paranoid schizophrenic," Mr. Perez wrote in a June, 1999, affidavit. "Ms. Harris also stated that she believed her brother would travel from his home in Canada

to Los Angeles to carry out his threat."

( Read the summary judgment in the 1999 case)

A California criminal docket includes a list of Mr. Brylla's aliases, which include Mark from Tahiti, Al from Bogota and Judge Harrigan. David McLane, the public defender assigned to Mr. Brylla's latest case, remembers his former client as interesting and eccentric, but not a serious threat.

"I believed he would have never carried out those threats," said Mr. McLane, who now works at a private law firm in Pasadena, Calif. "I thought he had

a gentle soul." Nonetheless, Mr. Brylla was facing eight years in prison for extortionate threats and, in consultation with Mr. McLane, changed his plea

to guilty, shaving six years off the sentence.

"You could argue that [the threat he made] wasn't a true threat, but that's an objective standard: Would a reasonable person feel threatened by what he said?" Mr. McLane said. "And I think a reasonable person would. That's why we made the decision to plea-bargain it out." Mr. Brylla was imprisoned for

27 months.

Mr. McLane remembers the initial altercation as being over a perceived threat to Mr. Brylla's rabbits – possibly that a roommate had threatened to hurt them. "He would do anything to protect his rabbits, and I think that was his downfall," the lawyer said. "I think it debilitated him and hurt him because he was so obsessed with rabbits that it dominated his life. In prison he was drawing pictures of rabbits."

Handwritten notes from this time in prison offer some introspection. "Having evaluated myself, for years now, and having successfully abstained from drinking, smoking or any drugs for over 10 years now, I enter a new era in

my life," Mr. Brylla wrote in neat, if somewhat childish, printing. "I cannot go into the deepest issues of my mind, but I do believe that I have matured way beyond the attitudes I had as a young man, when I was still unclear about the meanings of life, and my days were filled with eternal quests to date more and more beach bunnies, or take the challenge of the surfing glories to the limits, in the early dawn…"

Upon his release in June, 2002, Mr. Brylla was again deported. He stayed at Salvation Army shelters in both Richmond and Vancouver.

A sketch of a rabbit from Mr. Brylla’s prison journal.

HANDOUT

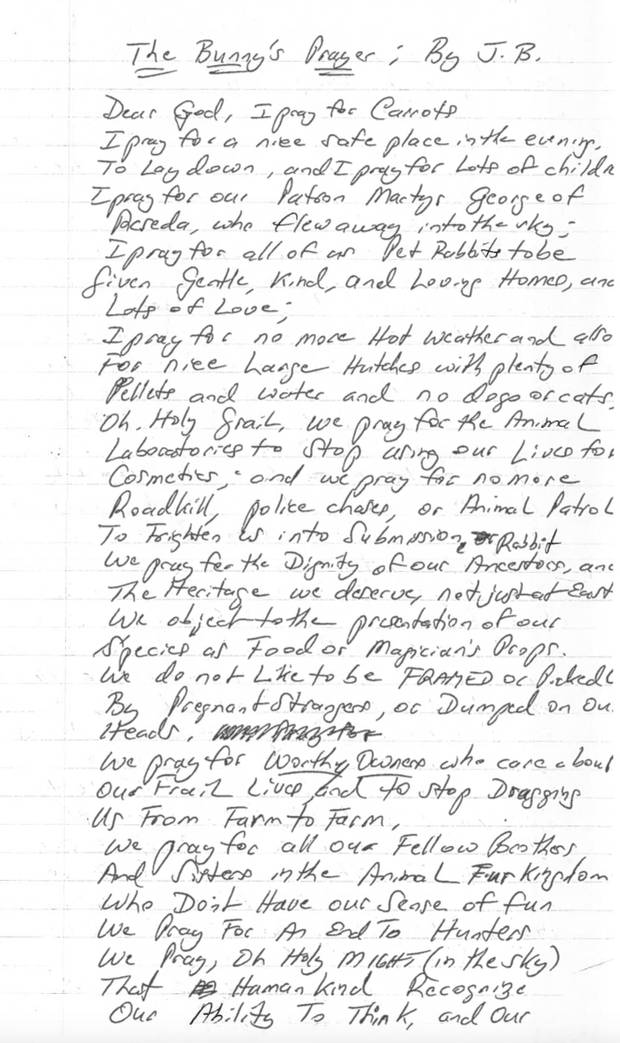

Around 2000, while he was in prison, Mr. Brylla wrote this poem from a rabbit’s point of view.

HANDOUT

To the Downtown Eastside

Mr. Brylla only kept out of legal trouble for eight months.

In February, 2003, he stole a purse belonging to Julie Grey, an administrative assistant at Peace Arch Hospital, as she was getting ready to leave for the day, according to transcripts from the Provincial Court of B.C. in Surrey. He called her twice the following week, demanding a $5,000 "finder's fee" to return the purse: "Pay the $5,000 or you're going to die," he allegedly said.

Police quickly traced the calls to two hotels in Richmond. They located Mr. Brylla, finding Ms. Grey's personal effects on him. During his arrest, he reportedly told police he suffered from schizophrenia and depression.

"In his personal letters," the transcript reads, "he also mentions that the U.S. government wrongly imprisoned him so they could use his prize show rabbits for space testing." Other rambling excerpts illustrate the disjointedness of his thoughts. At one point, Mr. Brylla told the court that George Bush would be attending proceedings the following day.

"I would like to talk to Mr. Bush," the judge said.

The transcript offers a rare account of Mr. Brylla, then 57 years old, talking about where he has come in life as of his 2003 prosecution. He initially dismisses the allegations against him as a "complete fabrication."

"Also, I'm disabled," he said. "I'm not a rich man, but I have my pride and dignity. And I came back here and I'm being singled out."

He said he was a zoologist – just one of many animal-related jobs he claimed to hold throughout his life, along with zoo curator, veterinarian and breeder of exotic animals. "I know more about animals than anybody in this country. Challenge me," he boasted. "Take me to the university. I'll tell you something that'll startle you. I have people in the United States that know who I am, that work in the medical industry, veterinary industry, who respect me highly."

Mr. Brylla was charged with two counts of uttering threats to cause death or bodily harm. He pleaded guilty.

At sentencing, the judge, Crown prosecutor and defence lawyer reached a sympathetic agreement that, for better or worse, pointed Mr. Brylla to Vancouver's Downtown Eastside. Noting his mental-health issues – "a non-specified type of psychosis," according to another psychiatric assessment – they agreed that a suspended sentence with conditions would be appropriate and that rehabilitation should be paramount.

"In my discussions with him, he sometimes does get off track and it's clear that he needs someone, or a facility, that he can go to and deal with whatever it is that he's dealing with," said defence lawyer Georgia Docolas.

"I could be wrong," Surrey Provincial Court Justice Jean Lytwyn said, "but

I think as much as the Vancouver Downtown Eastside has its problems, I

think that Corrections has more services there for people of Mr. Brylla's temperament."

Justice Lytwyn sentenced Mr. Brylla to 15 months' probation and connected him with the Lookout Emergency Aid Society in Vancouver.

Shayne Williams, executive director of the Lookout Society, remembers Mr. Brylla as a "colourful" and "eccentric fellow" who "had an air of wisdom about him." He said Mr. Brylla was on a BC Housing waiting list for subsidized housing, but his "infatuation" with rabbits complicated the situation. "Finding affordable housing is challenging, but when you start adding 10-plus bunny rabbits into the mix, you've got a completely different challenge on top of that," Mr. Williams said in an interview.

As a result, Mr. Brylla spent years without a permanent home, pushing his rabbits around in a cart, sleeping in churches, shelters and on the streets.

Mr. Swann recalled a week before Christmas about a decade ago, during a particularly frigid winter: Mr. Brylla, calling from Vancouver International Airport, asked for clean clothes and a new ski jacket. The reverend obliged, purchasing a few modest items at a second-hand store and taking them to

the airport.

There he met Mr. Brylla, wearing a dark coat that made him look dressed up despite the tattered clothing underneath. He also had a bunny in a suitcase, perched on an airport cart. It occurred to Mr. Swann that Mr. Brylla had been there for several days, pretending to be a traveller.

"I'm sure security picked up that he was sort of a harmless guy," Mr. Swann said. "I was just laughing. I thought, 'George, you're ingenious.'"

'No girlfriend, no bunnies'

For a few brief periods in 2007, Mr. Brylla stayed with Ms. Saidman in her West End home, sleeping on her living-room couch. He brought with him four rabbits. Ms. Saidman said she charged him $325 in rent, which was deducted from his welfare cheque.

However, this arrangement ended when he became increasingly erratic and threatening, Ms. Saidman said. In a document prepared for a dispute resolution hearing before the Residential Tenancies Branch, Ms. Saidman said that her efforts to collect rent angered Mr. Brylla. "I've had to call either 911 or the mental health Car 87 team several times after he began shouting at me and/or striding toward me with clenched fists," she wrote. "His threats initially would be to 'call the FBI' or sick the mafia on me, but more recently they involved physical violence, eg: he threatened to break my neck."

In 2011, Mr. Brylla moved into the Lookout Society's Sakura So residence in East Vancouver. A rooming house in a heritage building, the residence offered amenities such as a large communal lounge not found in most single room occupancy hotels.

Michael Nardachioni lived at the Sakura So with Mr. Brylla for nearly three years and the two became friends. Mr. Nardachioni, an artist who specializes

in murals and wildlife painting, said he found some of his former roommate's quirks amusing.

"The guy would have an expensive guitar and this expensive amp, but he couldn't play," Mr. Nardachioni said at Oppenheimer Park, where he often volunteers to serve coffee and met Mr. Brylla. "I asked him one day: 'Name the strings on the guitar.' He said, 'I don't know.' He just loved walking around with it, to look like a rock star."

He said Mr. Brylla was generally mild-mannered, but could occasionally be a "curmudgeon" when provoked – as when someone threatened to take his rabbits away. He was a good listener and an even better talker. The two would commiserate over relationship issues.

"When he was heartbroken, he'd come to me," Mr. Nardachioni said. And when my girlfriend went to hospital, he'd come and visit me. He was that type of guy. If you lent him an ear, he'd lend you an ear."

Mr. Nardachioni doesn't specifically remember any of Mr. Brylla's girlfriends but vaguely recalls that one or two he did see during their three years of friendship were much younger – in their 20s or 30s.

"He'd show me a picture now and then: 'Here's my sweetie.' In my mind I thought, 'Yeah, she's a sweetie, George, but only when you got your money, your pension cheque.' He had a lot of heart-broken stories. He had been, more or less, used."

A few of Mr. Brylla's friends said they believed he procured the services of sex-trade workers. Ellen Silvergieter, the advocacy office director at St. Paul's Anglican Church in Vancouver, said he often spoke of his girlfriends, whom she described as "ladies of the night."

"He'd say, 'I love them, they love me,'" said a chuckling Ms. Silvergieter, who first met Mr. Brylla in 2005. "Then the next phone call he'd tell me, 'They robbed me.' I'd have such a time not laughing because I knew what was

going to happen."

Ellen Silvergieter: A better system is needed for homeless seniors

1:48

Ms. Silvergieter and Mr. Brylla became friends over the years; she helped him register on housing lists and get disability benefits.

When the Sakura So closed for renovations in early 2014, Mr. Nardachioni and several others moved into Lookout's Tamura House residence two doors down. Mr. Brylla stayed at another shelter for a while, but ultimately chose to return to the streets. "He became distant toward the summer there, mostly because he had no girlfriend, no bunnies," Mr. Nardachioni said.

Judy Graves, who retired in 2013 as Vancouver's advocate for the homeless, says she knew Mr. Brylla for years, remembering a "gruff, very decisive, stubborn, cautious" man, afflicted with schizophrenia he said was so central to his personality he would not treat it.

"His life was very meaningful to him as it was," she said. "He believed this was his personality and none of us would want to give up our personality. Within his illness, there was a great deal of meaning."

A notice about the eviction is written at the tent city at Oppenheimer Park.

DARRYL DYCK FOR THE GLOBE AND MAIL

'Belonging' among the protesters

In July, 2014, a handful of homeless people set up camp in Oppenheimer Park in the Downtown Eastside. When city workers attempted to evict them, First Nations campers responded with their own eviction notice, citing aboriginal title – a right that had recently been affirmed by a landmark Supreme Court of Canada ruling. It was the beginning of a months-long standoff, the original few people eventually growing to an estimated 400.

On July 20, a CBC reporter and cameraman covering the story approached various campers for comment. One was Mr. Brylla.

He wore a beige jacket over a light blue golf shirt, with khaki pants. His camouflage backpack matched his floppy-brimmed hiking hat, pulled down over black, shoulder-length hair. Large tortoise-shell sunglasses covered much of his face.

"Go ahead, you can look in there," said Mr. Brylla, who told the news crew his name was JT. He pulled back an orange tarp draped over his tent and showed them its sparse contents. "My sleeping bag got soaked."

He told them about receiving the city eviction notice: "I could hear some rustling and some, 'Hey, wake up,' you know. Sarcastic, laughable tone. And, 'Here, we want to give you this [eviction notice].'"

Mr. Nardachioni said Mr. Brylla had housing available to him but chose the park instead. "I think what he wanted to do was join these protesters about housing," he said. "You know, that type of guy: 'If everyone's going to be camping, I might as well camp.'"

Another acquaintance of Mr. Brylla's who got to know him at one of the Downtown Eastside shelters said being in the Oppenheimer Park tent community was an empowering experience for Mr. Brylla.

"He talked about belonging there, which I had never heard him say before," said the man, who spoke on condition of anonymity. "I'd never heard him make reference to his group, or his people or belonging anywhere. Something kind of lit him up about being there. He found some attachment to the group."

By October, the situation at the park had grown tense. The City of Vancouver took the matter to court, seeking an injunction to dismantle the encampment. At the injunction hearing, Vancouver's assistant fire chief said that, during a recent inspection, fire personnel identified more than 100 separate violations of an earlier court order, such as open flames and smoking materials in and around tents. A ceremonial fire that had been ordered extinguished had been relit and was burning largely unattended.

A Vancouver police inspector said there were 364 calls to police regarding the encampment in the span of two months, resulting in 170 documented police incidents. A B.C. Supreme Court judge concluded the park had become unsafe and issued the injunction, ordering campers to vacate the park by Oct. 15.

Firefighters discovered Mr. Brylla's body shortly after 11 a.m. – the man in the green tent. On April 15, 2015, coroner Marianne Isis van Loon issued her final report into Mr. Brylla's death: He died of a brain hemorrhage, due to high blood pressure and a buildup of plaque in his arteries.

Reflecting on Mr. Brylla's life, Mr. Williams, the Lookout Society executive director, said he felt that the society had in some ways failed him. "We

tried to help him for a long time. We supported him," he said. "There were some successes … but the fact that he passed away in the park, not far from our head office, across the street from our Tamura residence – it's heartbreaking to hear."

The body of Joerg “Yogi” Brylla, also known as Bunny George, is taken away from Vancouver’s Oppenheimer Park after he was found dead on Oct. 15, 2014.

JOHN LEHMANN/THE GLOBE AND MAIL

The importance of mourning

In aspects of his life, Joerg Brylla worked to keep people at a distance. However, many of them came to say goodbye to him at a ceremony held at Glenhaven Memorial Chapel in East Vancouver on Dec. 5, 2014.

The minister Mr. Swann was there. So were Ellen Silvergieter and Bob Marwick – the church custodian who was once homeless himself and saw Mr. Brylla

as another soul without permanent shelter on the streets of Vancouver.

"This is the stuff he said to me: 'Nobody seems to understand me and what

I am doing with my bunnies, but I am supposed to be taking care of them,'"

Mr. Marwick later said.

Mourners sit at a the Dec. 5, 2014 memorial for Mr. Brylla in Vancouver.

JOHN LEHMANN/THE GLOBE AND MAIL

Judy Graves, who retired in 2013 as Vancouver’s advocate for the homeless, pays her respects.

JOHN LEHMANN/THE GLOBE AND MAIL

In total, there were about 20 people in a room capable of holding at least 100. Mr. Swann said they had a solemn responsibility: "It is very important we do this. Joerg Brylla mattered."

At the front of the room, flanked by lit candles, was a framed photo of Mr. Brylla – cradling a large white and grey rabbit.

"I have pretty clear confidence that George is looking down on us and he is amazed this is happening," Mr. Swann said. While Mr. Brylla didn't talk much about God, the minister said he saw a higher power in one aspect of his life: his rabbits. "He knew they were a gift from God."

When Mr. Swann called on the audience to come forward with their

stories about Mr. Brylla, Stephanie McKay, of the B.C. SPCA, stood at

the lectern weeping.

"The first time I met George," she said through sobs, "he scared the bejesus out of me." She told a story about working a night shift when a man turned up at the counter. "[He said,] 'Hey, I'm Bunny George.'"

He had a box with an injured wild rat he had found in the Downtown Eastside. She got to know Mr. Brylla well, she said, largely through issues around rabbits. She was sorry he didn't get more help with his problems toward

the end, she said.

Ms. Monteith, also of the SPCA, said Mr. Brylla had just a few simple things he wanted in life – and perhaps one more than any other.

"All he wanted to do was talk," she said, "and he wanted someone to listen."

With reports from Stephanie Chambers in Toronto and Amy Durica in Berlin