On the evening of July 19, 2015, Dr. Santa Ono was on vacation with his family in the Pittsburgh area when he got word that a campus police officer at the University of Cincinnati, where Dr. Ono was president, had shot an unarmed black man during an off-campus traffic stop.

The chaotic months that followed tested Dr. Ono's ability to listen, consult and reach out as he navigated a gauntlet of campus turmoil and media frenzy that he says was the most trying experience of his career as an academic leader.

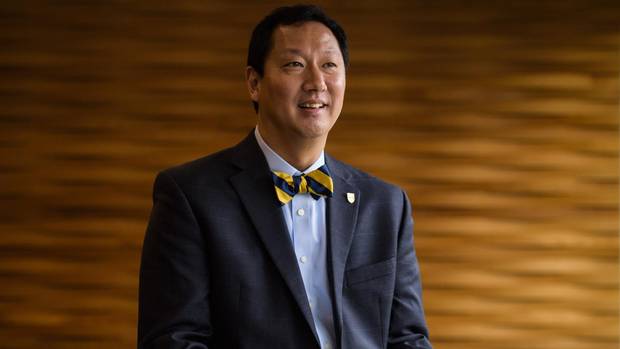

As he takes over the top job at the University of British Columbia, Dr. Ono says he is a "better leader" than he was a year ago, one prepared for the unique challenges UBC has faced in the messy aftermath of the resignation of former president Arvind Gupta after only one year of a four-year term.

When Dr. Ono came home last July, he learned that 43-year-old Samuel DuBose, who was African-American, was shot to death by 25-year-old Ray Tensing, a white officer with the campus police after an argument during a traffic stop. It was the fourth officer-related death in the 50-year history of the campus police. The previous three victims were African-American males. Two died after being tasered. Two, including Mr. DuBose, were shot.

In this July 29, 2015, file photo, photos of Samuel DuBose hang on a pole at a memorial near where he was shot and killed by a University of Cincinnati police officer.

Tom Uhlman/The Associated Press

Intuition, Dr. Ono said, is important in navigating such maelstroms.

"Unfortunately you don't have the luxury of time when things are breaking on an hourly basis as they did over the first few weeks."

Dr. Ono said that it was important to quickly figure out how to effectively and actively communicate with varied constituencies, including students – he made a point of mentioning African-American students – police, parents, and the city.

He had to figure out how to communicate more broadly with the community than would have been normal in most affairs related to his school.

Dr. Ono, who is active in his use of social media, said he had "social capital" in the community from previous outreach efforts.

"If I had no relationships and no social capital based upon social media, I think I would have been starting five steps behind."

The outreach included meeting Mr. DuBose's mother.

"There was a lot of tears," he recalled.

"I am a relational person so I hugged her. We cried together. I held her hands. I do think that's important."

Cincinnati civil-rights lawyer Al Gerhardstein helped the DuBose family secure a $5.3-million settlement with the university that includes free undergraduate tuition for Mr. DuBose's 12 children. He gives Dr. Ono some credit, but said the president could have been more proactive in dealing with signs of trouble at the campus department ahead of the tragedy.

"He's a man who has empathy and generally strikes me as wanting to do the right thing," says Mr. Gerhardstein.

"I am not going to say that he's perfect."

Ashley Nkadi, a member of the Irate 8 black student activist group – the eight refers to the percentage of African-American students at University of Cincinnati campuses – said Dr. Ono was generally responsive to the concerns of her organization.

The neurology graduate said Irate 8 met with Dr. Ono and his staff at least 15 times, and that the president was committed to enhanced accountability as part of varied outreach and policing reforms.

"With pressure, he's a good crisis guy," Ms. Nkadi, 21, said. "Definitely there needs to be pressure. I love president Ono. He's been a good mark on my college career. I love that he was here when I was here."

Mr. Tensing was charged with murder and fired. The former campus officer has entered a not-guilty plea.

Dr. Ono's new job helming UBC is a homecoming of sorts: He was born in Vancouver, the middle of three boys. One brother's a musical prodigy, the other a math genius.

His father was a noted math teacher at UBC. Dr. Ono earned a PhD in experimental medicine at McGill University. His career included teaching and research posts at Emory University in Atlanta, the Johns Hopkins School of Medicine, and Harvard Medical School. He was a provost and senior vice-president of the University of Cincinnati before being appointed president in 2012.

"My parents were afraid I would amount to nothing," he said. "Now the funny thing is that my parents, if you talk to them, would say that this middle child is now the president of the university where my dad had his first tenure-track job."

In the process, he nurtured his siblings.

When Ken needed some time away from his parents, he moved to Montreal where Dr. Ono was a graduate student. In his autobiography, Ken Ono speaks movingly about how he learned independence under his brother's guidance.

"That was my first project. I wanted to take him under my wing and love him and nurture him," Santa Ono said, speaking about his brother's recollections.

Ken Ono, now one of the most important mathematicians of his generation, once tried to take his own life and it was to his older brother, Santa, that the younger Ken turned. Santa Ono publicly disclosed last month that he too had attempted suicide in his teens and 20s. He made the revelation while speaking at a mental-health fundraiser in the aftermath of a high-profile student suicide at University of Cincinnati.

Dr. Ono told The Globe and Mail he realized that as a university president he had an opportunity to break the stigma by being more personal – so he talked about his own struggles.

The suicide of the young man in 2014 – his name was Brogan Dulle – led to conversations with students about why they were not accessing mental health services on campus.

They told him they were afraid that if they submitted health claims, their parents might find out.

So Dr. Ono found a way to offer five free counselling sessions each semester.

But aside from his academic credentials and the insights he's gained from his past and his position, Dr. Ono also brings to UBC another advantage: Middle children sometimes have to play peacemaker.

The departure of Dr. Gupta from UBC – succeeded by interim president Martha Piper – set off turmoil over issues of academic freedom that are still being resolved.

Dr. Ono hopes to produce a vision plan for the school as soon as he talks to every community group, ideally in his first year.

"Everything requires consultation," Dr. Ono said carefully.