Deirdre is leaning against an alley wall, prepping a needle full of crystal methamphetamine that could be contaminated with fentanyl. She and a friend have paused to cheer as an employee of a nearby needle exchange rushes over to revive an overdosing man.

"Breathe bro, breeeeathe!" another bystander shouts as he gently slaps the man's blue face while the employee preps oxygen and a syringe of naloxone that can reverse the deadly effects of opioids.

A small team of firefighters and paramedics take over. The first responders believe the man – Justin – is the one they revived in the same spot a day earlier.

Deirdre, who asked that her real name not be used, and her friend prepare their rigs and inject them into their arms, the scene in front of them no deterrent to the risk that could put them on the pavement in need of a similar lifesaving intervention.

It is 11:29 a.m. on a frigid Wednesday morning– the second-last Wednesday of December, when millions of dollars of social-assistance payments flood into the Downtown Eastside, or DTES. For recipients who regularly use drugs, this day – known in the neighbourhood as "Cheque Day," "Welfare Wednesday" or "Mardi Gras" – dramatically increases their risk of a fatal overdose.

Though much of Canada has felt the effects of the fentanyl-driven overdose crisis, British Columbia has been hardest hit, experiencing more fatal overdoses this year than in three decades of record-keeping. The death toll is expected to climb to more than 800. Two weeks ago, eight overdose deaths were recorded in the Downtown Eastside in a single day.

In the troubled neighbourhood, more than 6,300 people draw social assistance and more than half the 18,000 residents are thought to be drug users.

In the streets and back alleys, people slump against walls, their bodies suddenly limp as an overdose of synthetic opioids crashes their system, and their skin turns blue from a lack of oxygen. There are cries of people calling for help, shouting for the naloxone antidote kits that can reverse the effects of opioids. The names of loved ones lost are tagged on brick walls, in long lists. In the background, there is the constant wail and yelp of sirens.

On the final Cheque Day of 2016, seven reporters and two photographers with the Globe's B.C. bureau spent the day and night walking through the Downtown Eastside, witnessing the impact of the fentanyl crisis on most facets of life in the neighbourhood where the overdose epidemic has become troublingly normal.

The reporters saw first responders revive overdose victims who could have died otherwise, they saw outreach workers connect addicts with life-saving services, and they gained unprecedented and exclusive access to a mobile emergency room set up in the heart of the Downtown Eastside to quickly respond to the public-health crisis.

It would be a busy night.

"You clear a call, you get another one," paramedic Brian Twaites said during his shift. "You clear a call, you get another one."

Wednesday, Dec. 21

12:49 a.m.

Six loud beeps break into the radio frequency used by the Vancouver region's emergency services, followed by a computer-generated voice that announces what appears to be the first call of the morning. The call is directed to Fire Hall No. 2, the department's Downtown Eastside post where the overdose crisis has taken an especially brutal toll on first responders.

"Vancouver Engine 2. Respond emergency. Medical aid: overdose. 251 East Hastings St., near Main Street and Gore Avenue. Ovaltine Cafe."

8:02 a.m.

Just before sunrise, dozens of people are at Pigeon Park Savings, a credit union on East Hastings Street geared to the neighbourhood's low-income residents. The customers are here to get a chit reserving a place in line to cash their assistance cheques, which provide a single recipient with $375 for shelter and another $235 for other expenses. About three quarters have the shelter portion immediately directed to their landlords.

The night lineup at Pigeon Park Savings, where customers wait to collect their social assistance payments.

Ben Nelms/For The Globe and Mail

As a line forms for the 9 a.m. opening, Rory Sutherland and two other volunteers with the Downtown Eastside Neighbourhood House roll by with a bright yellow shopping cart full of bananas. The morning of every Cheque Day, the trio traverse the streets to dole out potassium boosts, which, Mr. Sutherland says, help combat hunger pains.

10:04 a.m.

As a gate rolls open, four people enter a pop-up supervised drug-consumption tent behind Pigeon Park Savings to pick up free needles provided by trained volunteers, many of whom are peers – former or current drug users from the neighbourhood. Advocates and health officials have set up about half a dozen sites like this one because, they say, the city's two federally sanctioned supervised-injection sites – including Insite, the first in North America – are not enough.

Outside the tent, street-level dealers sell various drugs to dozens of people injecting in the alley. More than 200 people will access the tent before the last group is hustled out at 10 p.m.

Staff at the tent want to make it as easy as possible for users to consume their drugs safely but do track each person's name and what substance they say they are using.

10:30 a.m.

In the Emergency Room at St. Paul's Hospital on Burrard Street, a young woman, her arms tattooed wrist to shoulder, lies propped up on one elbow. She looks angry, a typical reaction from someone waking from a drug overdose. Nearby, an elderly man in pyjamas is asleep with an IV taped to his forearm. Several people are being processed, but otherwise the gurneys sit empty, waiting for patients.

This, says Brian Lahiffe, a staff physician in ER, is about as quiet as it gets.

"Oh, this is two to three out of 10," he says calmly.

Over the course of the next two days, Dr. Lahiffe says the demands on ER staff will steadily ramp up as a flood of patients comes in from the DTES to the neighbourhood's closest hospital.

"In my experience, the actual day of welfare-cheque day is not necessarily the busiest; it's usually a couple of days after welfare-check day. When peoples' money runs out, they've spent it all, they've had it stolen, whatever, people then are coming in with withdrawal, they come in depressed, they come in with traumatic problems," he says.

"You give them a large dose of naloxone and you kind of precipitate withdrawal. They are in a busy, chaotic place surrounded by other patients who have overdosed and they are kind of pissed off. They don't really want to be there and they will leave. We can't stop anyone from leaving. We can say, 'this is a bad idea, you overdosed without knowing it,' but there is only so much we can do. We don't have the resources to hold all those patients here," he says.

St. Paul's has always dealt with drug overdoses, but there has been a flood of cases over the past year because of synthetic opioids fentanyl and carfentanil. Dr. Lahiffe has dealt with as many as 10 overdose patients on one shift. "We have I think 11 or 12 different docs on during the day so if you multiply that out, the numbers are huge."

10:35 a.m.

A group of street-level dealers who all appeared to be working together near the pop-up supervised consumption site have spent close to an hour watching a Globe and Mail reporter and photographer, but when approached for an interview, they don't reveal much.

One man who appears to be in his 20s says the overdose epidemic is "craziness," before resigning himself to his place in it.

"It is what it is, man."

10:47 a.m.

The Mobile Medical Unit, or MMU, a semi-trailer that has been converted into a satellite ER on wheels, is parked on West Hastings Street. Designed for use in natural disasters and other sudden medical emergencies, the facility was assigned to the DTES earlier in December by the provincial government and health officials to deal with the area's surge in overdoses. Nearly two hours after opening, the unit is quiet, with medical staff in relaxed conversation.

"We're not supposed to use the Q word," says a woman in a bright yellow reflective jacket standing outside, "because then all heck breaks loose afterward."

11:29 a.m.

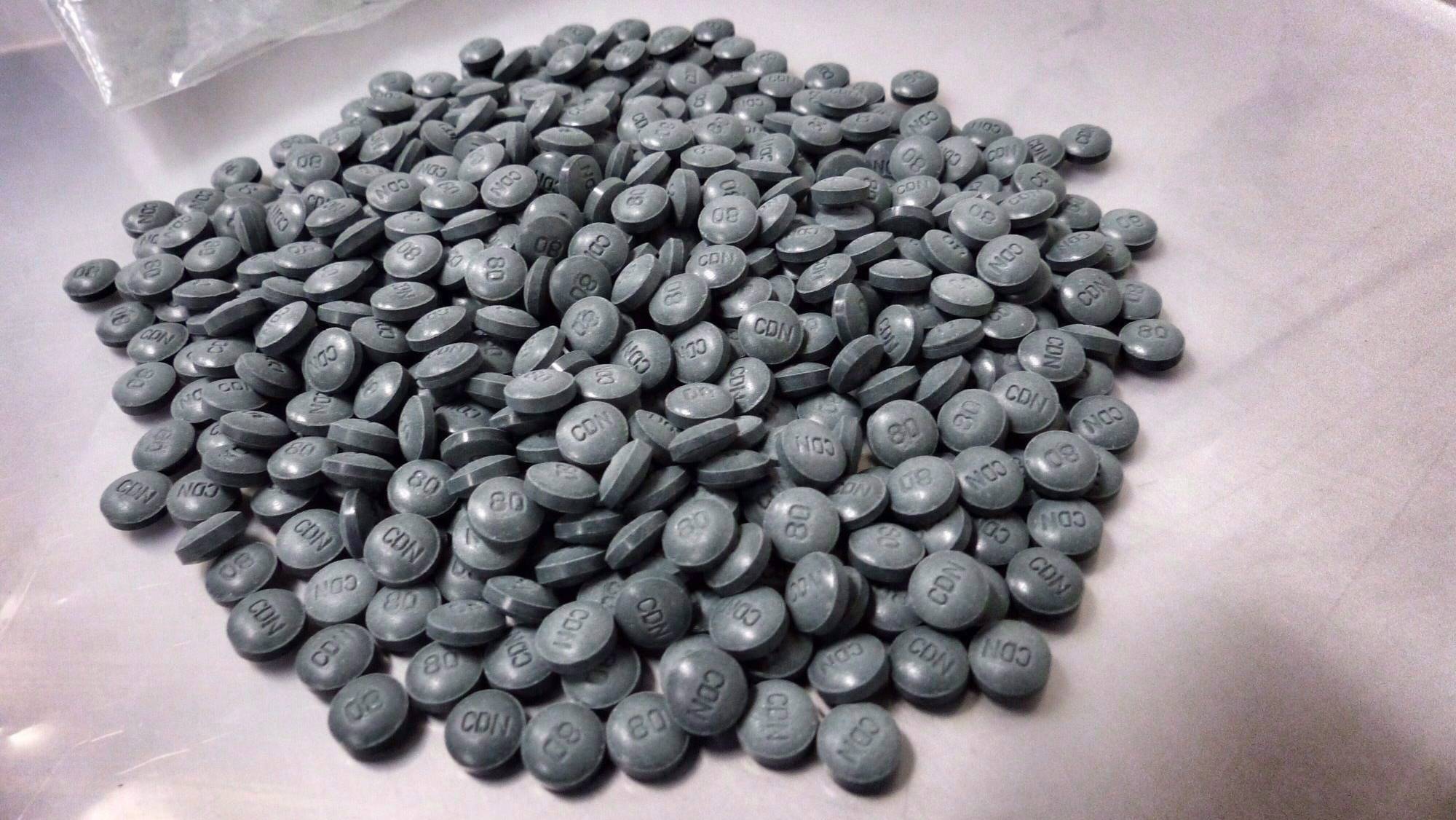

Outside The Needle Depot, where drug users can get clean rigs, a man falls in the middle of the lane and smashes his head on the asphalt. Moments after injecting drugs, he is on his back with his mouth agape, his hands splayed above his shoulders while his pupils roll up behind his eyelids.

Harold, who works at the needle exchange, runs over to administer oxygen and deliver the first of several doses of naloxone, a drug that reverses the effects of opioids.

First responders help an overdose victim in a Downtown Eastside alley.

RAFAL GERSZAK/FOR THE GLOBE AND MAIL

Two paramedics, who were already around the corner responding to an overdose at Insite, calmly walk over to attend to the unconscious man.

As the paramedics arrive, two firefighters hop out of an SUV to take over from Harold. They recognize the man on the ground as someone they saved from an overdose the day before in nearly the exact same spot. They believe the man's name is Justin and say he was released from jail two days earlier.

The man spits up an amber glob as the first responders help him up and onto a stretcher.

12:10 p.m.

At Insite, things are busy. A handful of people sit in chairs outside the injection room, waiting their turn. Two front-desk clerks manage the line. "It's Cheque Day and we're completely swamped," one worker says.

1:09 p.m.

At the Downtown Eastside Vendor's Market near Pigeon Park, Jonathon Findlay is looking for a well-known harm-reduction advocate so she can link him up with a nurse. He wants to begin detoxing and says he's ready for a prescription of Suboxone, a medication used to treat opioid addiction.

"It is a game changer – it's like you're a 'norm' again," he says of the treatment. "You don't 'fiend', you don't look for it – nothing. You have motivation, you still have drive, you're still happy, it's an antidepressant, it's all that. But you don't get high off of it."

1:15 p.m.

The MMU begins getting more traffic. Paramedics are bringing in overdose victims, but there are also drug users approaching the facility looking for naloxone kits and asking about treatment options.

1:30 p.m.

Shortly after being named executive director of Vancouver's Lookout Emergency Aid Society in 2014, Shayne Williams suggested staff get trained to administer naloxone.

He'd heard of several recent DTES overdoses and wanted to be prepared.

"I was saying, 'this is happening, and it's only going to get worse.' I just didn't know how much worse," Mr. Williams says at the Powell Street Getaway.

In 2016, staff at Lookout facilities, which include housing projects, emergency shelters and drop-in centres, have dealt with more than 360 overdoses .

"The cost of this epidemic – to police, to ambulance workers, to shelter workers, to the health-care system – is just incredible."

1:35 p.m.

Hugh Lampkin, a board member with the Vancouver Area Network of Drug Users (VANDU), says at least a dozen people he knew have died of overdose in 2016.

"We usually have pictures downstairs … After a while, you start running out of room," he says.

It's been about two weeks since the group opened what the local health authority describes as an overdose prevention room, where users can inject around volunteers armed with naloxone but aren't directly supervised as they would be at Insite. Mr. Lampkin says there have been a handful of overdoses since it opened, but none fatal.

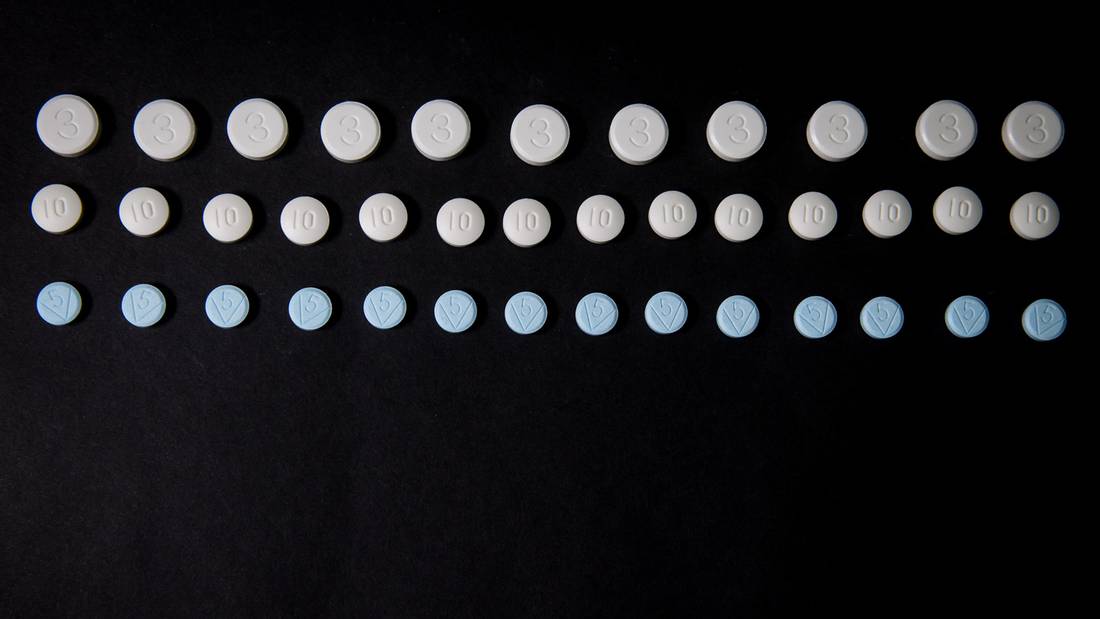

He says drug users have heard what's being sold on the street isn't heroin, but instead the more powerful fentanyl. Some don't believe it.

"Why do people believe that it's real heroin they're buying? Because they want it, right? It's that addiction … They want the real stuff so much," he says.

1:58 p.m.

In a crowded alley where people are using drugs, a man who gives his name as Smokey D is working on a vibrant painting on the cement block wall. It is a portrait of a goateed man with glasses and a fedora, with the caption: 'FEAR N LOATHING ON HEYSTINGS.' Smokey D, wearing red sneakers, baggy jeans and a blue baseball cap, says it portrays gonzo journalist Hunter S. Thompson.

A few metres away is a more piercingly personal work of art, with words daubed in blood-red paint. The message: "REST IN PEACE. TO MY WIFE SOULMATE DAWN HEATHER SANGSTER, NOV. 1970 – FEB. 2016. FENTANYL STOLE HER LIFE. PLEASE DON'T PARTY ALONE."

He says she was his girlfriend.

"She was clean for a long time, and then in February she went out and tried, just to do a couple of tokes to party. There was fentanyl in it, I guess, and she passed away and no one [saw her] for three or four days and then we found her," he says. "It was a total shock because she had been clean for so long, right?"

Asked about fentanyl, he says: "I hate it. It has killed a lot of people I know."

Beside the tribute were about 30 names, people he says had died from various causes, including overdoses. Also the caption: "I'm sorry if I forgot someone. No disrespect."

Artist Smokey D, left, paints an anti-Fentanyl art piece while his friend, Danny, keeps watch for police.

BEN NELMS/FOR THE GLOBE AND MAIL

He says he has done of lot of drugs, but is now on a program of prescribed opioids that he takes under medical supervision, with support services.

Smokey D says some of the drugs on the street now are so powerful they are used to tranquilize animals.

"That carfentanil stuff is for elephants and stuff … you can't even Narcan people back to life off it."

Cheque Day, he says, is crazy.

"So many people are spending all their money on everything," he says.

2:03 p.m.

"Today's welfare day. There's a lot of people using drugs," says outreach worker Jemal Damlawe, a former homeless drug addict now working for the Union Gospel Mission.

Mr. Damlawe is out with colleague Jen Smith on a street walk. The two are carrying bulging backpacks filled with socks, tuques, candy, oranges, yogurt, gloves and soap to distribute to people in need.

Since the fall, they have also been carrying naloxone kits. Mr. Damlawe has never administered naloxone but has called 911 for people overdosing.

He was on the streets for years using drugs and alcohol, but 11 years ago, on Christmas Day, he decided to beat his addictions. "If I had not done that, I would have died," he says. "I feel sad when I see people still on the streets because of addiction."

Mr. Damlawe says fentanyl is ruthlessly fatal.

"People just die very quickly. It's hard to see them. It just makes them like crazy," he says. "For them, they need a strong drug because of their addiction. Some of them, they take it and they don't like it. They're afraid of it because they see a lot of people die."

Ms. Smith says she has been trained to inject naloxone into muscles – legs, buttocks, biceps – but hasn't had to do so yet.

"A lot of my co-workers have," she says. "I think that when you see somebody in that state, you don't think about it, you just do it."

2:41 p.m.

The drop-in room of the Union Gospel Mission would normally be crowded, but only about nine people are there.

Cheque Day has emptied the space, leaving those on hand to watch the 1979 TV movie An American Christmas Carol with Henry Winkler from Happy Days as Scrooge.

The movie is offered as a distraction to keep people safe inside the centre. "It does work, but probably not to the extent anyone wanted it to," says Jeremy Hunka, a spokesman for the facility.

One man, who declined to give his name, says he is an addict taking methadone to reduce his own addictions. He says fentanyl is taking a heavy toll outside.

"I've known a few people to die, every day, I guess. It's a daily thing. You become desensitized to it."

3:07 p.m.

By now, the MMU has seen 13 patients, more than twice the load by this time on an average day. Four men, all just revived with naloxone injections, sit in stalls separated by curtains. A man enters the facility and in exasperated terms tells physicians his Suboxone prescription was disrupted because he could not afford the deductible. He is afraid of relapsing. Keith Ahamad, an addictions physician, starts him on the addiction-treatment medication Suboxone immediately. The man gets up to leave a short time later, visibly grateful. He stops at the door and turns around: "You guys are awesome. Thank you so much."

3:15 p.m.

Mr. Lampkin at VANDU is administering CPR to a man who has overdosed. The man was injecting drugs with his wife in the overdose prevention room, but collapsed in the lobby. Mr. Lampkin is performing chest compressions as three firefighters arrive. They administer a dose of naloxone and the man ultimately comes to.

3:53 p.m.

Douglas Zack sits on a chair in front of a pile of stuff he was hoping to sell off the sidewalk.

His inventory includes items he collected at recycling bins in what he describes as "Yuppietown"– the Olympic Village neighborhood where a one-bedroom condo sells for about $700,000.

Up for sale today with Mr. Zack are shoes, cosmetics, toys, bicycle helmets and other items. He doesn't expect any opioid addicts to buy anything. "The druggies don't shop here. They're more likely to steal something," says the 70-year-old, dressed for the chill in multiple layers capped by a long tuque.

5 p.m.

A woman is brought into the MMU for her second overdose since being released from jail four days earlier. For drug users, the relative abstinence that comes with incarceration means decreased tolerance, making them particularly susceptible to overdose after they're released. The gaunt woman sits in a chair and, quite literally, cries for help. She does not want to use any more, she says. Dr. Ahamad starts her on Suboxone immediately.

The Mobile Medical Unit in the Downtown Eastside.

BEN NELMS/For The Globe and Mail

5:30 p.m.

Insite has already seen 12 overdoses.

The MMU has now treated 20 people. At least half were started on assisted treatment with methadone or Suboxone.

Fire Hall No. 2 has responded to four overdose calls in the past 90 minutes. The night is just beginning.

6:12 p.m.

For three years Jay Slaunwhite has lived in the Balmoral Hotel on East Hastings.

He says a few weeks ago, people were running up and down the hall looking for naloxone. Because he had extra doses, he put a sign on the door saying he had some to offer.

"I had them there and people needed them," he explained, saying he underwent training at a community centre on how to inject the life-saving drug and provide CPR.

He says there have been 12 to 16 knocks at the door since he put up the sign. A few times, he had no naloxone to offer. "They continued their run looking for some and hopefully they found it," he says.

Sometimes, the endings are not happy. Last week, a man just out of jail overdosed, and his friends came to collect the treatment. "He was put into a coma. I guess it was really harsh. I don't know if he's going to pull through."

On one occasion, he tried to save someone himself.

"She was going to die," he says of the woman, an acquaintance who was in his room at the time.

"She came in and she used and she only used half of what she had. She immediately went under, and started turning blue. It's really not an attractive look on anyone," he says.

He administered the naloxone, ran into the hallway to get someone to call 911, then did CPR until the paramedics came and were able to save her.

"She wouldn't intentionally shoot herself up with fentanyl. She didn't know," he says. "She was mad [after she was revived]. People tend to get angry when that happens." But she has not stopped using. "The fear of fentanyl is not going to stop an opiate addiction."

7:47 p.m.

Meaghan Thumath, a registered nurse with the B.C. Centre for Disease Control, concludes a hectic shift at the MMU. "Many patients were asking for prescription heroin (which is currently unavailable)," she writes in a text message. "Overall it was really rewarding to have outreach, public health, emergency and addictions folks all working together under one roof co-ordinating care. I'm hopeful we're making a difference."

7:54 p.m.

Brian Twaites, an advanced-care paramedic four hours into his B.C. Ambulance shift in the DTES, reports a busy night. "It's been constant, just constant," he says. "You clear a call, you get another one. You clear a call, you get another one. That's pretty much the norm every day, but with the opioid crisis it's even more. We've seen high call volumes for a long time but with the opioid crisis it's even more."

Along East Hastings Street, the scream of sirens seems endless.

9 p.m.

Maggie Cochrane recently called a special staff meeting for her team: 14 people who run the Colonial Hotel, a single-room occupancy building managed by Atira Women's Resource Society.

At the meeting, staff talked about what they were doing – carrying naloxone, stepping up rounds to check on tenants who are known drug users – and what else might be done.

"The burnout rate is already high in this field and this makes it worse," Ms. Cochrane says, as a siren wailed outside her window. "But we show up, suit up and go to work."

9:24 p.m.

Outside the MMU, Mr. Twaites says he has responded to 11 calls in the past five hours, most of them overdoses. "Everybody is working to the max: the fire, the police, the paramedics," he says. "We're just non-stop now. It's draining."

9:28 p.m.

It's 3 degrees outside and people are lining up for a bed at the Union Gospel Mission on Burrard Street. The shelter is only half full.

A staff member tells people the rules of the house: "There is zero tolerance in here; that means no cigarettes, e-cigarettes, alcohol. If you're caught using, you're out, automatically." A prayer follows and they're finally taken up to their beds.

Staff says there hasn't been a high demand tonight. Often it's at full capacity, but tonight there will be only 60. "When people receive their income assistance cheque, many will be able to afford temporary accommodation like an inexpensive hotel, or possibly time in an SRO," says Jeremy Hunka, a spokesman for the Mission.

9:30 p.m.

Steve Creeman, 62, prepares Heroin at VANDU’s overdose prevention site.

BEN NELMS/FOR THE GLOBE AND MAIL

VANDU closes in half an hour and staff are cleaning up.

Martin Steward is at his desk. Mr. Steward, now 44, says he has been using cocaine "in all its forms" for more than three decades. He considers himself a "functioning addict."

He lived on the streets of Toronto from the time he was 12 until he was 18. He then moved to Nova Scotia, where he got married, had a son and divorced, before ending up on the carnival circuit for six years.

He went back to school when he was 30 and ultimately ended up in the oil patch, where he could earn more than $5,000 in a single week. He was later diagnosed with Crohn's disease and colon cancer (now in remission) and is on disability. He currently takes in about $800 per month.

Mr. Steward says he came to Vancouver for medical treatment, but also because his brother was an addict living on the street. He says VANDU "opened my eyes to a whole new reality of drug use."

"I needed to help," he says.

10:45 p.m.

Paramedics attend a call to an overdose victim in front of Insite. The man is lying unconscious, sprawled across the sidewalk when paramedics put an oxygen mask over his face. They inject naloxone into the man's abdomen and, after a couple minutes, he wakes up. A friend tells the overdosed man he put all of his belongings in a bag and handed it over to the paramedics. Other people nearby aren't paying attention; they are getting ready to inject.

11:08 p.m.

At the MMU, seven people sit in various states of consciousness: a couple folded over together, two men leaning forward, two sitting upright, one leaning on his side in a chair. "I just broke up with my girlfriend," a man in his mid-30s says quietly. He looks to have had an awful night. "You guys are so great. Thank you for helping me. I miss my girlfriend."

11:10 p.m.

As Kimberly Corbett, program manager at the Gastown Hotel, makes her rounds, she greets each tenant by name, even those who have lived in the SRO for a short time. It's important, she says, to build a sense of community.

That community was rocked recently by the overdose death of Marnie Crassweller, a resident. She wasn't widely known as a drug user. So her death – which came after she used drugs, alone, in her room – shocked her friends and acquaintances, including fellow "binners" who packed a November memorial service.

She is survived by two daughters.

Since Ms. Crassweller's death, Ms. Corbett – like so many people in the neighbourhood – finds herself worrying about who might be next.

On her rounds, she knocks loudly on the doors of communal washrooms in the hotel, checking to see that nobody's in trouble. If she's worried about tenants, she'll knock on their doors, too.

"Hello?" she says, pushing the door open in front of her. "It's me Kim, I'm coming in."

11:25 p.m.

The MMU, which typically sees 15 patients a day, takes its 29th patient.

Thursday, Dec. 22

2 a.m.

Richie Carter prepares his drugs on East Hastings Street, not far from Insite.

BEN NELMS/FOR THE GLOBE AND MAIL

In front of him are two naloxone kits. When he hears shouting down the block, he jumps to his feet, a kit in hand, and runs to where the commotion is. It turns out to be a false alarm; someone using a wheelchair miscalculated a curb and went tumbling to the street. Mr. Carter returns to his spot and readies a syringe.

"If you're not going to be at Insite, you better be where people are around."

2:41 a.m.

Paramedics at St. Paul's Hospital are just outside the ambulance bay attending to two patients on the sidewalk. One of them had to be dragged from the other side of the street to the hospital by three police officers.

2:53 a.m.

The DTES fire hall has responded to 44 calls in one night shift – with four hours to go. Twenty six of those calls were overdoses. The fire hall has effectively seen its call volume double since fentanyl hit in recent years.

"This is when the headache creeps in," firefighter Don Robinson says in a text message. "By now, nerves are frayed from overstimulation. It's important to stay alert. This is when accidents are prone to happen."

3 a.m.

The mobile medical unit closes after a hectic 18 hours treating a total of 29 patients.

3:21 a.m.

Mr. Twaites, the paramedic, continues working beyond his 12-hour shift as volume is still high. He has attended 26 calls.

6:34 a.m.

In the predawn quiet, Gary Granger, a shelter worker, stands on a dark street drinking coffee and preparing for his shift, which begins at 7:30, when clients are required to leave the shelter until it reopens in the evening. He's worked here for 15 years.

The overdose crisis is hitting people who are already down on their luck, he says, adding that many of them feel forgotten. He's written a song he calls TUKA – The Unknown Addict – he plans to share at a shelter social gathering.

"I was writing it about one person, and then I realized I was writing it for everybody," he says. "Someone makes some wrong choices and then one day, they're in the ground." – as in dead and buried.

7:10 a.m.

Mr. Robinson finishes his 14-hour shift. He bikes home – a 25-minute ride – and collapses into bed. The DTES fire hall responded to a total of 53 calls, 26 of them drug-related. It is believed to be a record number; the only other comparable night Mr. Robinson can recall is the 2011 Stanley Cup riot.

He calls the situation frustrating. Adequate treatment has been lacking for at least a decade, he says.

"This is a problem that needed to be addressed years prior to this happening. It's not what's happened in the last eight months that's turned this into a crisis," Mr. Robinson says.

"It's frustrating. We're just pawns. As firefighters, we can't change anything. All we can do is go to where we're dispatched. We'd like to think we can change that, but there's not much we can do. We can only respond."

MORE FROM THE GLOBE AND MAIL: