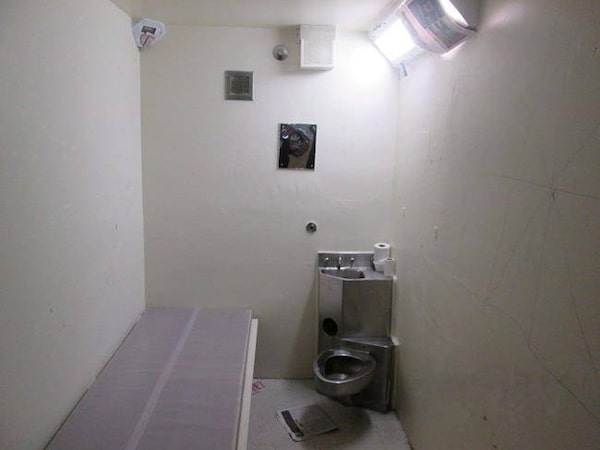

A solitary confinement cell is shown in a handout photo from the Office of the Correctional Investigator. A British Columbia man facing extradition to the United States says he could spend the rest of his life in solitary confinement because American authorities have identified him as a “snitch.”The Canadian Press

A British Columbia man facing extradition to the United States says he could spend the rest of his life in solitary confinement because American authorities have identified him as a "snitch."

Colin Martin, who is alleged to have been involved in a cross-border drug-trafficking ring, is seeking leave to appeal to the Supreme Court of Canada.

Mr. Martin's application says he has already spent more than four years in solitary since the RCMP warned him his life was at risk and has suffered a serious psychological decline. He is currently out on bail, pending the resolution of the extradition process.

One of Mr. Martin's lawyers said he was only aware of one other extradition case involving the United States in which an applicant expressed concern about prolonged solitary. The applicant was unsuccessful and the case did not reach the high court.

Mr. Martin's argument says his case is of national and public importance.

"[Mr.] Martin must choose between threats to his physical well-being in the general population or the extremely detrimental effect of solitary confinement on his mental health," reads his argument to the Supreme Court, filed this week.

"Either choice may sign his death warrant."

The federal Department of Justice said it is aware of Mr. Martin's application and the government's response will be delivered through the court process.

Mr. Martin's last-ditch application comes as a case challenging the use of solitary confinement in federal prisons has just concluded in B.C. and awaits judgment. A similar case continues in Ontario.

The Globe and Mail has reported extensively on the prevalence and effects of solitary confinement, beginning with a 2014 investigation into the suicide of Edward Snowshoe after 162 consecutive days in segregation.

Mr. Martin's argument says the federal Minister of Justice must assure anyone who faces a substantial risk of prolonged solitary confinement upon extradition has meaningful human contact on a daily basis and the same rights to education and exercise as other inmates.

The argument says the Supreme Court has recognized that the punishment or treatment "reasonably anticipated" in the country requesting extradition is a relevant factor in any decision.

But while the death penalty and infliction of torture are obvious factors, the argument says, the risk of prolonged solitary confinement has not been viewed in the same manner.

American officials have alleged that Mr. Martin participated in a conspiracy to transport drugs across the Canada-U.S. border. They have said the trafficking ring took MDMA and marijuana to the United States and cocaine to Canada. They have alleged that Mr. Martin's role was to provide the helicopters used to move the drugs.

The U.S. indictment – which named several individuals – was issued in December, 2009. It said Mr. Martin previously called the Drug Enforcement Administration and offered to assist as an informant.

Mr. Martin has denied the statements, though the United States has maintained that he made them.

Less than a week after the indictment was issued, the RCMP advised Mr. Martin there were credible threats against his life.

Just over one month later, the RCMP advised him of further threats.

Mr. Martin has a number of Canadian drug convictions and was incarcerated for much of 2010 through 2014. A psychological report prepared in November, 2014, said he had spent nearly all of the previous 4 1/2 years in solitary.

"Most notably since Mr. Martin has been incarcerated and placed in segregation cells and units, he has become severely depressed and suicidal, such that a number of different clinicians have appraised him as representing at least a moderate to high risk for suicide," said the report, prepared by Dr. Robert Ley.

Federal Justice Minister Jody Wilson-Raybould ordered Mr. Martin's surrender to the United States in February, 2016. The B.C. Court of Appeal upheld her decision in June. The minister said the actions of U.S. officials did not amount to an abuse of process and the U.S. correctional system would be able to adequately treat Mr. Martin's mental health.

Lawyers for Mr. Martin said the conclusion reached by the minister and the appeal court, that spending time in solitary confinement was not sufficient reason to refuse surrender, was "out of step with the growing international consensus that prolonged solitary confinement is a form of torture."

The United Nations' Mandela Rules define solitary as the confinement of inmates for 22 hours or more a day without meaningful human contact. They prohibit prolonged solitary confinement of more than 15 consecutive days.

One of Mr. Martin's lawyers, as he seeks leave to appeal, is Joseph Arvay, who was also one of the lawyers in the B.C. constitutional challenge that just concluded. Mr. Arvay represented the BC Civil Liberties Association and the John Howard Society of Canada and frequently cited the Mandela Rules during the proceeding.

Mr. Martin, 45, is of Métis heritage and his argument goes on to question what impact that should have on such cases, "to ensure that extradition proceedings do not further contribute to the alienation of aboriginal persons from the justice and penal systems."