Larry Doherty was in good hands, steady hands, like the metal ones you can find on an automaker's assembly line. The 64-year-old bean salesman from Bow Island, Alta., had come to the University of Calgary's Department of Clinical Neurosciences and Hotchkiss Brain Institute to undergo arteriovenous malformation surgery – to untie the tangled blood vessels in his brain.

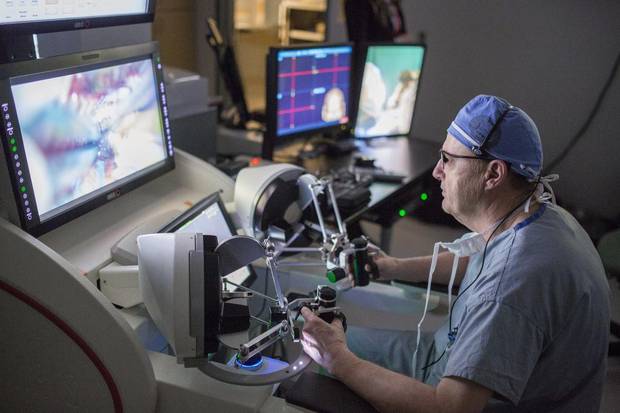

When everyone in the operating room was ready, the operating surgeon began his work sitting in a whole other room surrounded by computer monitors, including one with a 3-D image of Mr. Doherty's brain. Using specially designed hand controls, Dr. Garnette Sutherland manoeuvred the robot to its ready position. For Mr. Doherty, it was the first time in his life he had undergone surgery. For the physician, the number of robot-assisted operations he has performed is now somewhere over 70.

The next day, Dr. Sutherland talked about how far robotic surgery has come and what could happen in the not so distant future. "In 100 years," he said, "humans won't be operating on humans." Robots will, and that means fewer and fewer humans involved in the process. It's a scary thought given how science fiction and pop culture have portrayed robots as heartless pragmatists trying to Control-Alt-Delete humankind. They can be as detached as HAL from 2001: A Space Odyssey or as imposing as Gort from The Day the Earth Stood Still.

Neurosurgeon Dr. Garnette Sutherland looks over his patients scans before surgery.

Chris Bolin/For The Globe and Mail

But inside his Calgary office, all is safe. Machinery meets medicine in a non-menacing way, as it should. It was Dr. Sutherland, as a professor of neurosurgery, who facilitated the idea of placing a high-field magnetic resonance imaging scanner in the operating room and using it in real time to show surgeons precisely where they need to be. Once locked on location, Dr. Sutherland goes to work with the neuroArm, a considerably smaller version of the Canadarm that was developed for NASA and had 90 missions in space.

"We brought medicine and engineering power together," explained Dr. Sutherland, who has described what he does as a "multidisciplinary project that crosses the boundaries between university, industry and community towards the achievement of a formidable goal."

People from around the world come to Dr. Sutherland to have a lesion removed or blood vessels fixed because they believe in his operative skills. His reputation was honed by the successful 2008 robotic surgery performed on a 21-year-old woman suffering from multiple brain tumours. (She is alive and doing well.) It was a grand debut for Dr. Sutherland and the neuroArm as the first MRI-compatible surgical robot.

Larry Doherty, 64, from Bow Island, Alta, in surgery.

Chris Bolin Photography Inc/For The Globe and Mail

NeuroArm was a collaborative effort involving the University of Calgary, space engineering company MacDonald, Dettwiler and Associates (MDA) and others such as Deerfield Imaging of Minneapolis, Minn., with its SYMBIS surgical system. When all was done, neuroArm could reach the smallest areas inside the brain and do the necessary repairs without so much as a twitch.

"Dr. Sutherland has always got a vision for the future," said Tim Fielding, a senior systems engineer for MDA who has worked with the professor. "He attracts people … He's a great leader."

NASA learned of the new, go anywhere technology having previously partnered with Canadian researchers to build the Canadarm for the space shuttle program. The space agency has been impressed enough with the neuroArm to present its makers with three awards, including the Exceptional Technology Achievement medal. Dr. Sutherland's group was contacted by the Colorado-based Space Foundation and told it was being inducted into its Technology Hall of Fame. Dr. Sutherland also received the Order of Canada in 2012 for his neurosurgical contributions.

"We had a private person check out [Dr. Sutherland] to see if he was doing all the good things we had heard about," said Kevin Cook, the Space Foundation's communications and marketing man. "When I got to meet him here [in Colorado Springs, Colo.] he was quite excited. He was very grateful and fairly humble, too."

Neurosurgeon Dr. Garnette Sutherland performs a brain surgery using the NeuroArm.

Chris Bolin/For The Globe and Mail

It takes a great deal of work to reach a lofty status in the medical-robot business, especially since robotic surgery is now being applied in a multitude of ways, for colon and rectal surgery, gastrointestinal surgery, neurosurgery and coronary bypass. So many options; only so many robots.

The first acknowledged use of a robot for surgical purposes was in 1985 when the Puma 560 took part in a neurosurgical biopsy. In 2000, the da Vinci surgery robotic system was the first to be approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration. And last year, Vancouver General Hospital surgeon Dr. Brian Toyota became the first in Canada to combat brain tumours with robotic laser heat technology. He did so by using NeuroBlate, a Winnipeg-produced technology that is minimally invasive and also uses MRI to pinpoint tumours during surgery.

"There are more [facilities doing robotic neurosurgery]. But not like this," Dr. Sutherland said, referring to how the Hotchkiss Brain Institute fosters a learning environment so students and experts from around the country, around the world, can meet and discuss how to build a better robot.

The experts include Fang Wei Yang, a robotics technician who was born in Wuhan, China. He was a plastic surgeon before he met Dr. Sutherland and moved to Calgary. Liu Shi Gan is a robotics engineer born in Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia. She has a PhD in biomedical engineering from the University of Alberta.

Then there's Kourosh Zareinia, an assistant professor for the medical robots program. He was born in Stanford, Calif., but moved to Iran with his family. He graduated from the University of Tehran with a Master of Science in electrical engineering. He went on to the University of Manitoba, where he rose to become dean of the Faculty of Engineering.

Mr. Zareinia was hired by the U of Calgary's Department of Clinical Neurosciences and appointed adjunct assistant professor. He is supervising three postdoctoral fellows and leading research projects. He said every time he attends a conference or seminar, the questions begin.

"They want to know about our robots," Mr. Zareinia said. "The U.K., India, Nepal, Japan, I have texts from them wanting to know what we are doing next … I love my job."

Larry Doherty after meeting with his Neurosurgeon Dr. Garnette Sutherlan.

Chris Bolin/For The Globe and Mail

And the work continues. Twelve neuroArm-related projects have been patented, others are in the process. The irony is that while robots are being constructed to do the work of humans, those same robots lack a measure of what it takes to be human, foibles and all.

"The main challenge for machines to take over from human surgeons may be their limited ability to make an intelligent guess, based on experience, judgment, thinking on your feet or natural instincts," Dr. Sutherland said. "Having said that, a machine able to perform a small portion of a surgery autonomously could be closer than we think."

Mr. Doherty's surgery for arteriovenous malformation was another by-the-robot success. He insisted he felt well enough after his surgery to go home and thanked those who told him he was a surgery waiting to happen. The more he thought, the more reasons he came up with to have his first-ever surgery, be it done by a neurologist or a robot.

"I was having seizures and my family doctor told me not to drive any more," Mr. Doherty said. "Before that, I used to drive through a school zone to get to work. I couldn't live with myself if something had happened."